|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 26(5); 2023 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: This study was conducted to identify the current status of domestic agricultural business operations related to the design and business model of care farms in order to manage quality for the certification of excellent Agro-Healing Facilities (AHFs) that meet the needs of the times given the increasing demand for agro-healing.

Methods: An online survey was conducted of 170 agro-healing business entities nationwide, and the collected data were frequency-coded using SPSS Ver. 25. Chi-square was conducted for frequency analysis and significance was tested by one-way ANOVA.

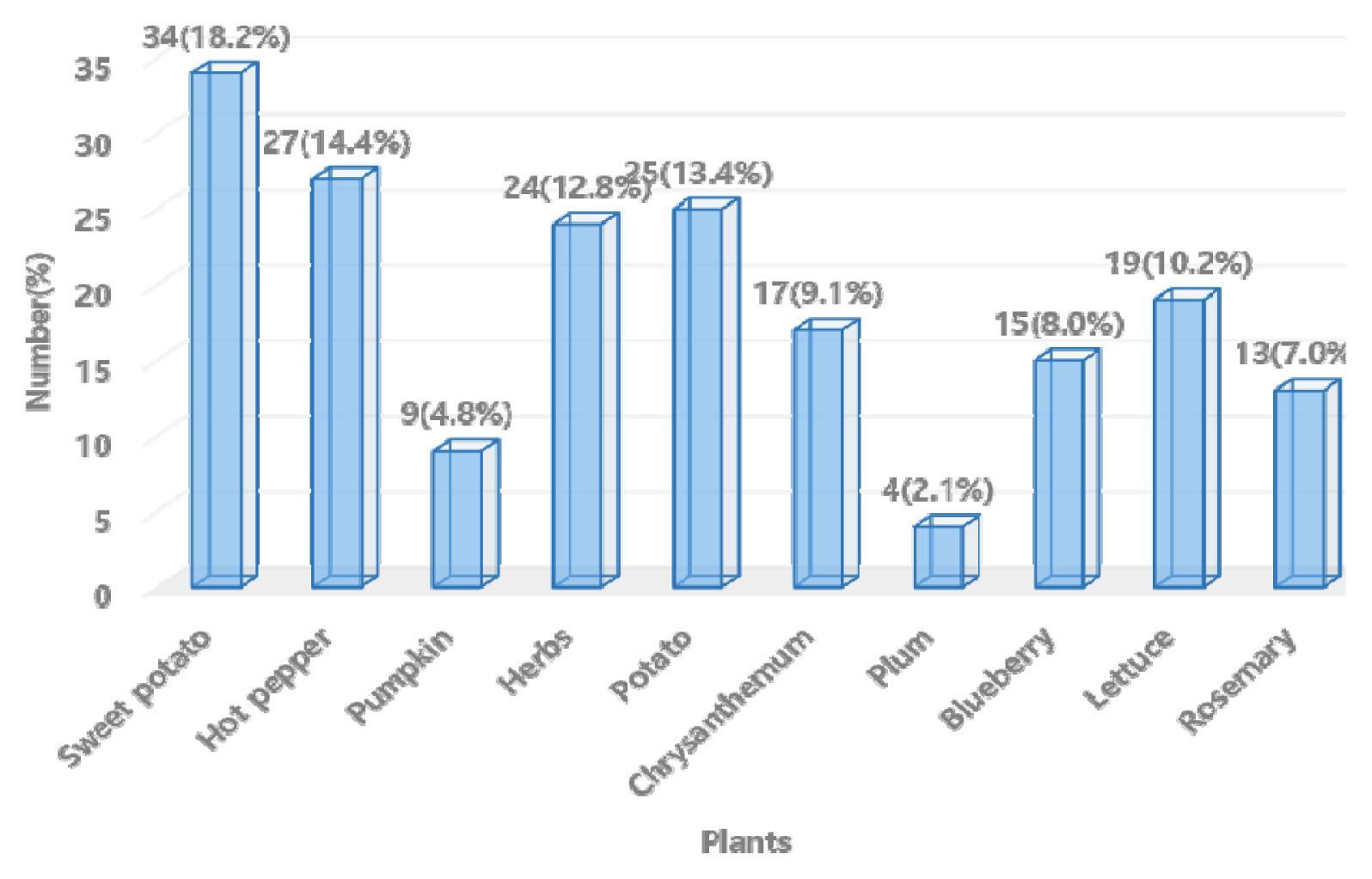

Results: For the type of business, individual businesses were the most common (118 businesses), and for the total sales of the business, 30 million won to less than 100 million won was the most common (57 businesses. For the total number of employees, businesses with 2 workers were the largest group (35.9%). In terms of the qualification standards for the CEOs and employees of care farms, 152 employees (89.4%) had completed education in agro-healing. In terms of the land use status of care farms, 141 individual businesses (82.9%) owned lands, and the average land area was 123,626.05 m2 for farmland, 178,195.98 m2 for land, and 62,511.51 m2 for plant cultivation area. The most frequently planted plant was sweet potatoes, and the least planted was plum. For functional plants mainly used in the programs, vegetables were the most common, followed by flowers, fruit trees and landscaping plants, special and food crops, and herbs. A non-parametric Žć2 test of all items was statistically significant (p < .001).

Conclusion: The AHF certification scheme, which will be implemented from the end of June 2024, will select excellent facilities from among existing AHFs to provide correct information to the public and lay a foundation that will support the spread of sustainable agro-healing. It is expected that this study will provide useful basic data for establishing care farm business models and seeking future direction for care farms.

Methods: An online survey was conducted of 170 agro-healing business entities nationwide, and the collected data were frequency-coded using SPSS Ver. 25. Chi-square was conducted for frequency analysis and significance was tested by one-way ANOVA.

Results: For the type of business, individual businesses were the most common (118 businesses), and for the total sales of the business, 30 million won to less than 100 million won was the most common (57 businesses. For the total number of employees, businesses with 2 workers were the largest group (35.9%). In terms of the qualification standards for the CEOs and employees of care farms, 152 employees (89.4%) had completed education in agro-healing. In terms of the land use status of care farms, 141 individual businesses (82.9%) owned lands, and the average land area was 123,626.05 m2 for farmland, 178,195.98 m2 for land, and 62,511.51 m2 for plant cultivation area. The most frequently planted plant was sweet potatoes, and the least planted was plum. For functional plants mainly used in the programs, vegetables were the most common, followed by flowers, fruit trees and landscaping plants, special and food crops, and herbs. A non-parametric Žć2 test of all items was statistically significant (p < .001).

Conclusion: The AHF certification scheme, which will be implemented from the end of June 2024, will select excellent facilities from among existing AHFs to provide correct information to the public and lay a foundation that will support the spread of sustainable agro-healing. It is expected that this study will provide useful basic data for establishing care farm business models and seeking future direction for care farms.

Agro-healing (care farming or social farming) is an industry that creates added social or economic value through the use of various agricultural and rural resources and related activities to recover, maintain, and improve the health of the people (Article 2 of the Act on Research, Development and Promotion of Healing Agriculture). In advanced countries in agro-healing, including Japan, the Netherlands, and Belgium, it is referred to by various terms, including agro-healing, social farming, green care farming, and farming for health (Gim et al., 2013). As interest and investment in agro-healing, which implies the ŌĆ£therapeutic use of farming practices,ŌĆØ increases (Hassink, 2002; Hassink and van Dijk, 2006; Parsons et al., 2010; Sempik and Aldridge, 2006), and the paradigm of global and national health care policies shifts toward preventive health care, agro-healing is creating new synergies with health care.

In Europe, the concept, purpose, domain, and targets of social farming are clearly established for each country, and policy support at the national level is active, making it a major sector of the agricultural industry. In addition, social farms are officially connected to schools, communities, hospitals, and the like, are helping to provide new therapeutic resources to local communities, support the emotional stability of participants, and increase farm incomes (Dessein and Bettina, 2010; Di lacovo and OŌĆÖConnor, 2009; Hine et al., 2008). In South Korea, after the Act on Research, Development and Promotion of Healing Agriculture (hereinafter referred to as the ŌĆ£Agro-Healing ActŌĆØ) came into effect on March 25, 2021, the publicŌĆÖs interest in care farming increased, promoting the psychological, social, cognitive, and physical health of the people by converging existing productive agriculture with healthcare and social welfare (Park, 2019; Lee et al., 2020). Led by the Rural Development Administration (RDA), research has been conducted on developing agro-healing content and building a foundation for agro-healing that includes creating new jobs and reducing social costs (Jeong et al., 2019; Jang et al., 2020). In addition, RDA (2023) suggests securing consumer confidence through the Agro-Healing Certification and promoting the commercialization of agro-healing as major strategic tasks of the ŌĆ£1st Comprehensive Plan for Research, Development and Promotion of Agro-HealingŌĆØ (2022~2026). However, compared to the beneficial effects and business assessment of overseas agro-healing, which has been promoted for a relatively long time (Bragg, 2020; Hassink et al., 2020), in South Korea, activities that utilize the therapeutic function of agriculture in various places including farms, rural villages, hospitals and clinics, welfare centers, health promotion centers, and counseling centers are just beginning, and as such it is still a challenge to clearly present a picture of care or community farms. Therefore, to establish and spread social farming as an industry in agricultural and rural areas, it is urgently necessary to present resource input and performance models for creating care farms, including business space creation for care farms, resource utilization, program operation, and profitable value creation. In particular, analyses should be conducted according to the survey scope of the actual conditions stated in the Enforcement Rule of the Agro-Healing Act, including creation and operation of healing agricultural facilities, service provision, and status of users and workers. In response to these needs of the times, business plans related to the creation of care farms are needed in connection with recreational culture, including the socially disadvantaged classes, disease prevention for the general public, and recovery in daily life. Through a status analysis, the status of care farms should be clearly determined, and based on this, guidelines for systems, policies, and creation of care farms should be established. With this in mind, the aim of this study is to explore the direction of newly emerging agro-healing business models; to determine the operation status of agricultural business entities (ABEs) in South Korea based on the standards of the excellent Agro-Healing Facilities (AHFs) Certification Scheme established by RDA (2023) to secure consumer confidence through quality control of agro-healing; and to provide basic data that can contribute to the establishment of service strategies of agro-healing and plans for future care farm businesses.

In this study, a survey was conducted on the operation status of care farms for 40 days from October to November 2022 to explore a business model for care farms. Among ABEs operating care farms nationwide, 170 were targeted that were engaged in businesses related to agro-healing programs, landscapes, or experiences. To ensure the representativeness of samples, a non-face-to-face online survey was conducted by Company B, a professional research agency located in Seoul, South Korea.

The survey items included care-farm management characteristics and manpower, and the status of agro-healing facilities and environments. The care-farm management characteristics item consisted of 5 questions: start year of care farming business, business type, whether representatives are farmers or not, total sales of business, and sales of care farming. The agro-healing manpower item consisted of 6 questions, including the gender and age group of representatives, the number of regular workers, the number of field instructors and volunteers, the number of temporary and daily workers, the number of unpaid family workers, and whether workers had qualifications related to agr-ohealing. The status of agro-healing facilities and environment item consisted of a total of 15 questions: 2 questions about the scale of land use, including land ownership status and area; and 7 questions about the use of plant resources, including plants mainly planted, plants that generate profit through cultivation, functional plants that generate profit, plants whose cultivation in programs leads to sales revenue, plants frequently used in programs, functional plants mainly used in programs to generate profit for healing farms, and plant information sources (Table 1).

The data collected from a total of 170 responses were organized in Excel 2016 (Microsoft, USA) and then analyzed using the Windows version of SPSS 25.0 (IBM, USA). A frequency analysis was conducted on all domains of care-farm management characteristics, manpower, facilities and environment, and normality and chi-square tests were performed to verify goodness-of-fit. To determine the relationship between land ownership type and cultivation area, an analysis of variance (ANOVA), a statistical technique that compares variances across the means, was performed, and the significance was evaluated using DuncanŌĆÖs multiple range test (DMRT) at a confidence level of 95% (p < .05). A survey of priorities was conducted with multiple choice questions on the status of plants frequently planted on farms, plants that generate sales revenue through cultivation, plants whose cultivation through programs leads to sales revenue, and plant information and selection criteria.

Looking at the regions in which care farms were operated, Gyeonggi-do had the largest number of care farms (29 respondents, 17.1%), followed by Chungcheongnam-do (26, 15.3%), Jeollabuk-do (25, 14.7%), Gyeongsangnam-do (24, 14.1%), and Seoul with the fewest number (1, 0.6%). The year in which agro-healing was started by ABEs ranged from 2011, when research on social farming began, to 2020, when the number of care farms hit a peak at 107 (62.9%). This seems to result from the introduction of the 6th industrialization of agriculture policy, which sought the convergence of processing, sales, and services to increase added value, improve farm incomes, and create jobs in the existing cultivation-oriented agriculture (Kim and Heo, 2011). The most common business type was individually-operated businesses at 118 (69.4%). This is similar to the findings of Yoo et al. (2021b) and Roberta et al. (2020), and seems to be because small-scale private farms accounted for the absolute majority. The number of care farms whose representatives were farmers accounted for the majority at 165 (97.1%). Businesses with total sales ranging from 30 to less than 100 million won represented the largest group at 57 (33.5%), while businesses with agro-healing sales ranging from 10 to less than 30 million won were the largest group at 46 (27.1%). This was consistent with the findings of an Analysis of Performance Factors according to the Operation of Care Farms reported by Hong et al. (2023). In testing whether the data of care-farm management characteristics are normally distributed, both Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests found that they did not follow a normal distribution with a significance probability of p < .001, verifying the goodness-of-fit (Table 2). To be certified as an excellent AHF in the future, agro-healing businesses are required to promote sustainable development and improve service quality by strengthening the overall management readiness and capacity suggested by RDA (2023), including operation plans for agro-healing services for service operation and management by the businesses; customer satisfaction surveys and feedback; preparation and management of promotional materials; customer relations through consent forms for customer rights and completion of human rights courses; cooperative network construction; and business management to establish sound accounting and fair contract management.

The gender breakdown of the representatives showed more males (92, 54.1%) than females (78, 42.3%), and their average age was 56.94 ┬▒ 9.88. To evaluate the overall readiness and capabilities of manpower for service operation and management of ABEs, the status of manpower by employment type at care farms was surveyed. ABEs with one full-time worker were the largest group at 63 businesses (37.1%), followed by those with 0 workers (48 businesses, 28.2%), 2 (34, 20.0%), 3ŌĆō5 (15, 8.8%), and 5ŌĆō6 (15, 8.8%), 10 (7, 4.2%) and 11 or more (3, 1.8%). ABEs without temporary or daily workers accounted for the majority at 106 businesses (62.4%), followed by those with 2 workers (22 businesses, 12.9%), 1 (20, 11.8%), 3ŌĆō5 (13, 7.6%), and 6ŌĆō10 (9, 5.3%). ABEs without field instructors or volunteers were the majority at 159 businesses (93.5%), most of which operated agro-healing business with farm personnel. This was followed by those with one person (6 businesses, 3.5%), three or four people (2 each, 1.2%), and 2 people (1, 0.6%). ABEs without unpaid family workers accounted for the majority at 83 businesses (48.85%), followed by those with 2 people (41 businesses, 24.1%), 1 (34, 20.0%), 3 (8, 4.7%), and 4 (2, 1.2%), and 5ŌĆō7 (2, 1.2%). ABEs with a total of 2 employees were the largest group, with 61 businesses (35.9%), followed by those with 3 employees (38 businesses, 22.4%), 4 (16, 9.4%), 1 (13, 7.6%), 5 (12, 7.1%), and 6 (9, 5.3%); other ABEs were operated with 7, 10, and 11 employees (4 businesses each), 8 and 15 (3 each), and 12, 14, and 16 (1 each). This was consistent with the report by Yoo et al. (2021b) that care farms with 3ŌĆō5 employees (36.8%) and 1ŌĆō2 (35.8%) accounted for the majority, operating on a small scale. In both Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, the status data of care farm manpower did not follow a normal distribution with a significance probability of p < .001, verifying the goodness-of-fit (Table 3).

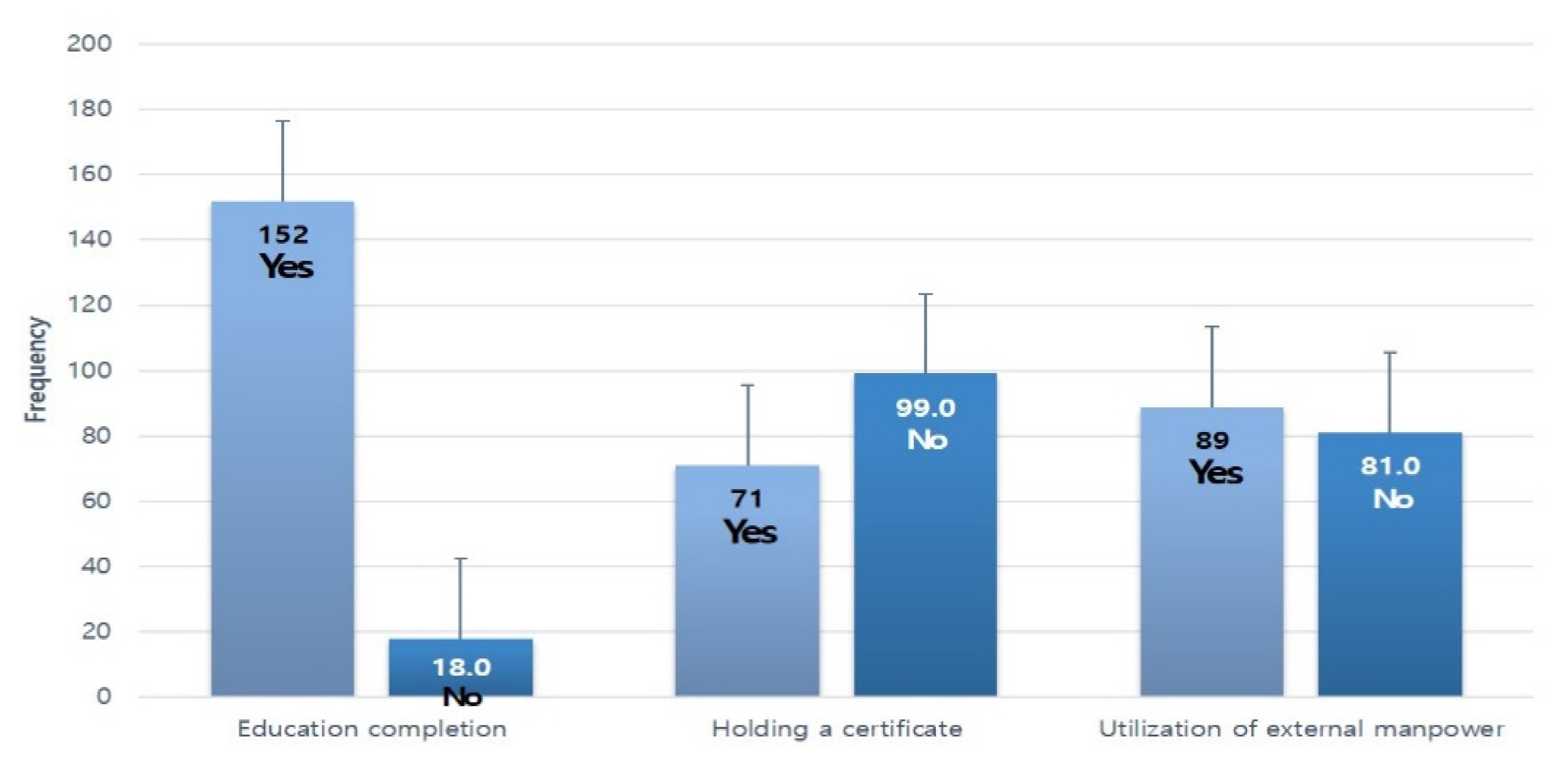

Based on the qualification standards for care farm representatives or employees, the number who completed training courses for agro-healing specialists was 152 (89.4%), most of which had an understanding of agro-healing. The number of ABEs with personnel holding at least one of the relevant national qualifications (e.g., agro-healing specialist or social worker) or private qualifications (horticultural therapist or vocational rehabilitation specialist) was somewhat insufficient at 71 (41.8%) out of 170 businesses. It was found that 89 businesses, or 52.4% of survey respondents, were using external manpower qualified as agro-healing specialists or horticultural therapists (Fig. 1).

RDA provides training courses for AHF operators, although this was not covered in this study. For the Excellent AHF Certification Scheme in the future, it seems that the ŌĆ£completion of training courses for AHF operatorsŌĆØ is considered a requirement in the human resources domain. As it may be a difficult task to secure sufficient experts in the early stages of agro-healing, RDA has not suggested a specific number of operating personnel as a requirement for excellent AHF certification. However, as shown in the findings reported by Bae et al. (2019) that the importance of AHF operators is above average in agro-healing, it seems that securing the expertise of service operators and the appropriate number of operating personnel are very important requirements for quality control of agro-healing. In addition, RDA (2023) reported that the preparation of job specifications, service personnel history management, employee training, criminal history management and the like are required as standards for excellent AHF certification. To strengthen the expertise of agro-healing and maintain care farms, a support system that substantially reflects the concept and purpose of agro-healing should be sought; for example, beyond employee training at the level of farms, continuous refresher training, which is organized by RDA and implemented by local governments, for nationally qualified agro-healing specialists and those who have completed training courses for AHF operators.

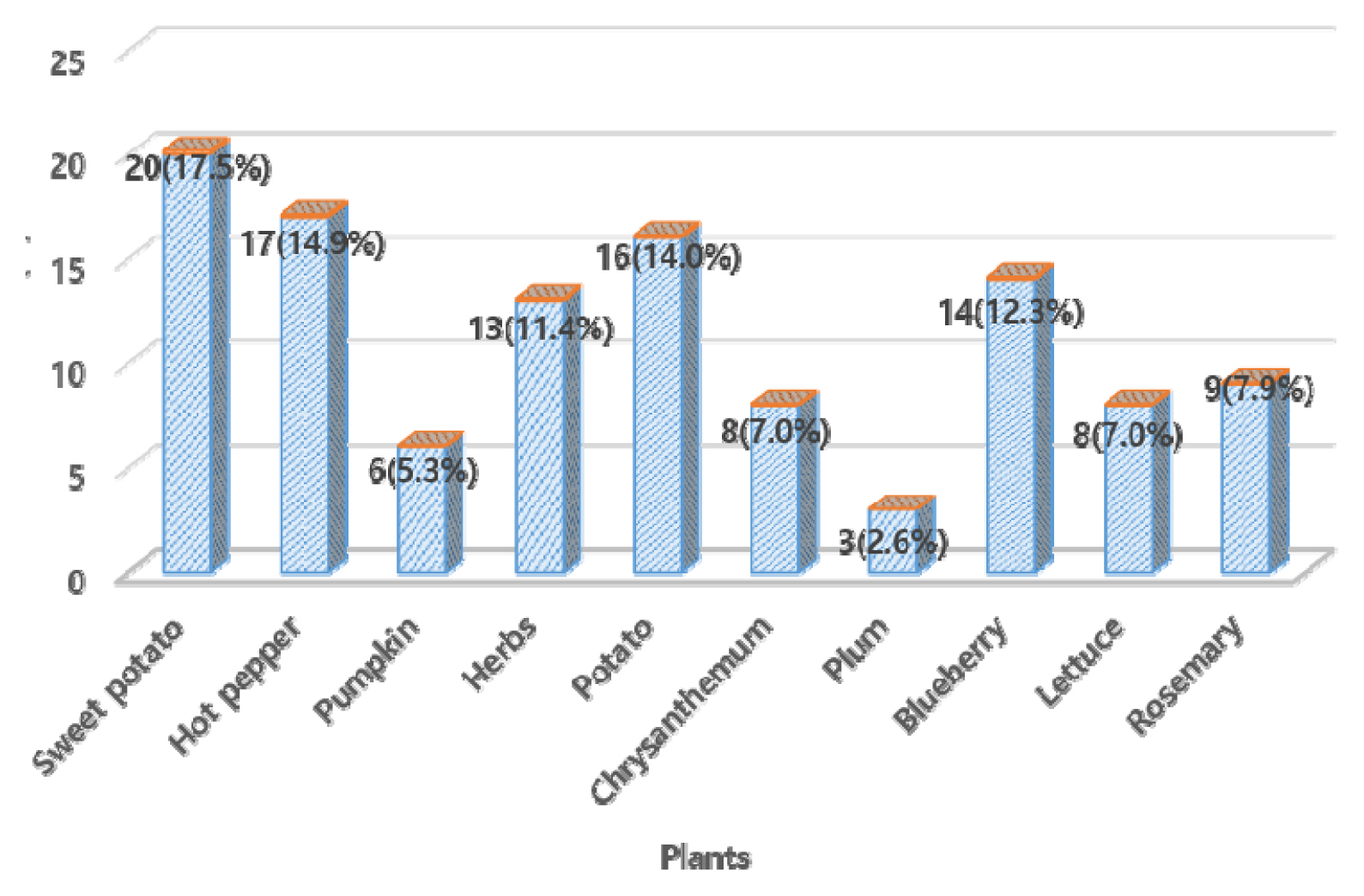

Yoo et al. (2021a) reported that the most used resource for agro-healing programs in the field is plants (58.8%) in their study on the development of strategies for establishing healing agriculture. Gim et al. (2013) also reported that plants are the most utilized resource based on literature research and focus group interviews with experts. Thus, the subjectsŌĆÖ responses to a multiple-choice question about five or more plants that were mainly cultivated as plant resource materials in care farms were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 2. Sweet potatoes were grown the most at 34 businesses (18.2%), followed by hot peppers (27 businesses, 14.4%), potatoes (25, 13.4%), herbs (24, 12.8%), lettuce (19, 10.2%), and chrysanthemums (17, 9.1%), blueberry (15, 8.0%), rosemary (13, 7.0%), pumpkin (9, 4.8%), and plum (4, 2.1%). For plants that generated sales revenue through cultivation, sweet potatoes were also the most common, at 20 businesses (17.5%), followed by hot peppers (17 businesses, 14.9%), potatoes (16, 14.0%), blueberries (14, 12.3%). %), herbs (13, 11.4%), rosemary (9, 7.9%), chrysanthemum & lettuce (8, 7.0%), pumpkin (6, 5.3%), and plum (3, 2.6%; Fig. 3). This was consistent with the report by Yoo et al. (2021a) that agro-healing in Europe and the United States mainly uses plant materials produced on farms, and participants receive agro-healing services by participating in agricultural production or related activities. It indicates that agro-healing is based on participantsŌĆÖ involvement in production activities on farms.

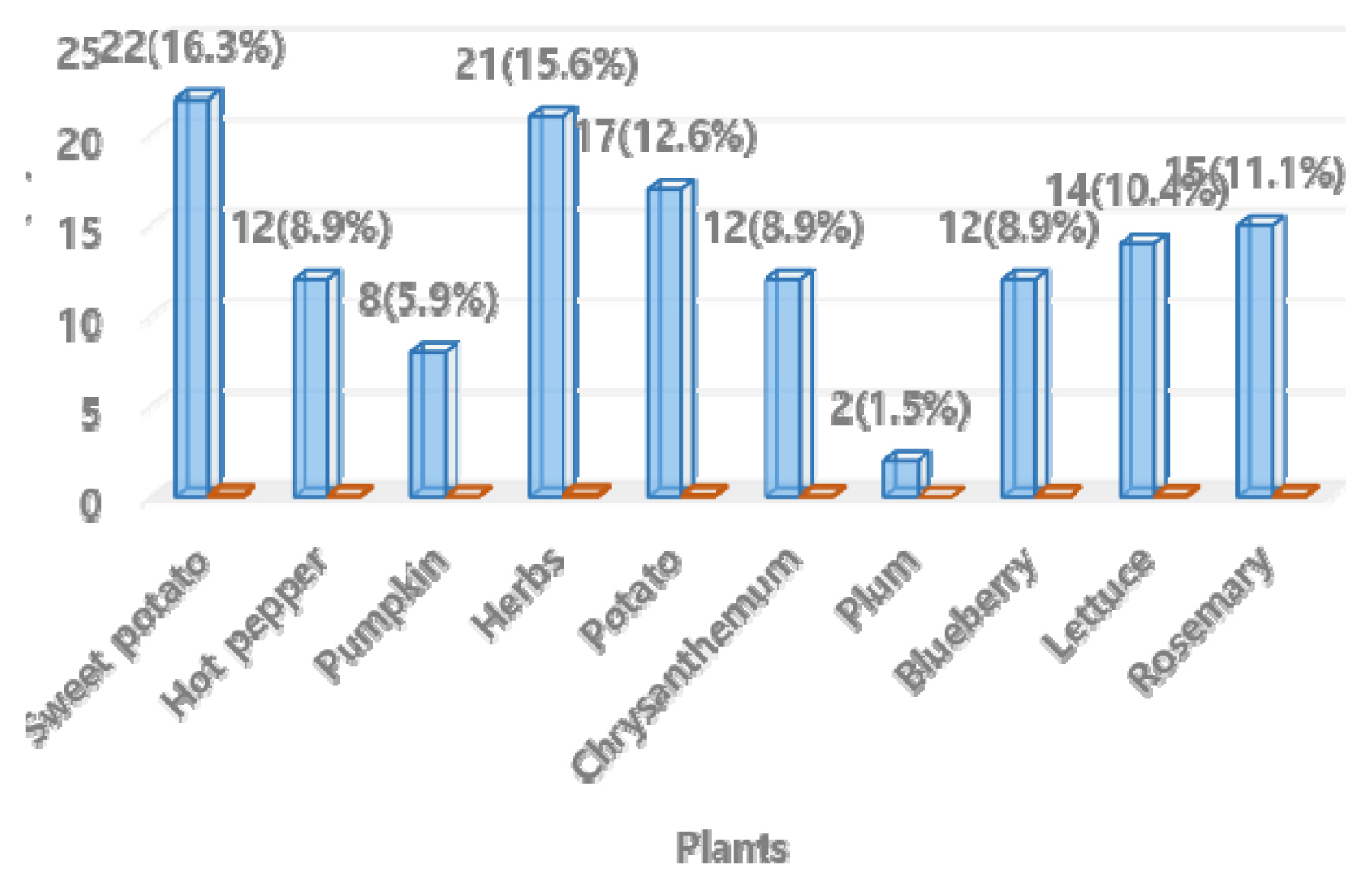

For functional plants grown in care farms, including plants that generate profits through cultivation, sweet potatoes were also the most common at 21 businesses (19.4%), followed by herbs (16 businesses, 14.8%), hot peppers (14, 14.0%), potatoes (12, 11.1%), blueberries and rosemary (11, 10.2%), lettuce (9, 8.3%), chrysanthemum (7, 6.5%), pumpkin (4, 3.7%), and plum (3, 2.8%; Fig. 4). Overall, the plant whose cultivation through the program most directly led to sales revenue was sweet potatoes, while plum had the least connection with sales revenue. Regardless of sales revenue, for plants frequently used in agro-healing programs, sweet potatoes were the most common at 22 businesses (16.3%), followed by herbs (21 businesses, 15.6%), potatoes (17, 12.6%), rosemary (15, 11.1%), lettuce (14, 10.4%), blueberry, pepper, and chrysanthemum (12 each, 8.9%), pumpkin (8, 5.9%), and plum (2, 1.5%; Fig. 5). Of plants frequently used in the program, among those used for therapeutic functions, herbs accounted for the largest group at 20 businesses (23.5%), followed by rosemary (14 businesses, 16.5%), sweet potato (13, 15.3%), blueberry and chrysanthemum (9 each, 10.6%), potato and pumpkin (5 each, 5.9%), hot pepper and lettuce (4 each, 4.7%), and plum (2, 2.4%).

Both Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests found that data of plants that are frequently used in agro-healing programs or have therapeutic functions did not follow a normal distribution with a significance probability of p < .001, verifying the goodness-of-fit (Table 4).

For functional plants mainly used in programs to generate profits for care farms, vegetables were the most common, followed by flowers, fruit trees and landscaping plants, special and food crops, and herbs (Table 5).

By analyzing the responses to a multiple-choice question about sources from which information on plants used in care agriculture programs was obtained, it was found that searching websites on the Internet was the most common, which was the response given by 90 businesses (27.4%), followed by regional Agricultural Research Services or Agricultural Technology Center (81 businesses, 24.7%), RDA (53, 16.2%), acquaintances who run care farms (51, 15.5%), professional books (46, 14.0%), and other (7, 2.1%). Here, ŌĆ£otherŌĆØ included education provided by schools, public health centers, and associations. In addition, for the selection criteria for plants used in agro-healing programs, participantsŌĆÖ response was the most common, given by 104 businesses (31.8%), followed by the degree of therapeutic functionality (100 businesses, 30.6%) and ease of continuous management (e.g., diseases and pests; 66, 20.2%), ease of initial cultivation (e.g., labor and time; 49, 15.0%), and less cost (8, 2.4%). By evaluating the normality of information source data on plants used in agro-healing programs, in both Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, it was found that they did not follow a normal distribution with a significance probability of p < .001, verifying the goodness-of-fit (Table 6).

The average land area of AHFs was 123,626.05 m2 for farmland, 178,195.98 m2 for land, and 62,511.51 m2 for plant cultivation area. Based on land ownership, in terms of farmland area, private ownership was the largest at 148,580.67 m2, followed by other at 3,384.17 m2, rental at 2,433 m2, and corporate ownership at 1,861.65 m2; for land, private ownership was the largest at 214,444.04 m2, followed by other at 4,768.50 m2, corporate ownership at 1,493.82 m2, and rentals at 450.00 m2; for plant cultivation area, private ownership was the largest at 74,410.58 m2, followed by corporate ownership at 6,699.00 m2, other at 2,449.00 m2, and rental at 1,083.33 m2 (Table 7). This was slightly different from the findings reported by Yoo et al. (2021b), in which the total land area of care farms was 3,331,636 m2 and the average land area per farm was 31,431 m2.

As for the land use status of care farms, private ownership was the most common, with 141 businesses (82.9%), followed by corporate ownership (17 businesses, 10.0%), and rentals and other (6 each, 3.5%). Here, ŌĆ£otherŌĆØ included mixed types, such as private ownership and rentals or private and corporate ownership, as well as village or regional community farms, and state-owned land (Fig. 6). This was similar to the findings of Yoo et al. (2021b) that 75.5% of care farms were privately owned land, and that the fewer workers on a farm, the more likely the land was to be privately owned. DuncanŌĆÖs multiple range test performed as a post hoc test showed that there was no statistically significant difference between land ownership and area (Table 7).

Based on the general characteristics of care farms, men owned the largest area for farmland (7,539 m2), land area (1,806 m2), and plant cultivation area (4,956 m2). Those in their 70s and older owned the largest area for farmland (14,002 m2) and plant cultivation area (8,451 m2), while those in their 60s owned the largest area for land (2,535 m2). The ABEs whose representatives were farmers had the largest farmland (6,167 m2) and plant cultivation area (3,783 m2), while those whose representatives were not farmers had the largest land (9,240 m2). For business type, individual businesses had the largest farmland at 6,442 m2, and incorporated companies had the largest land and plant cultivation area at 1,890 m2 and 4,790 m2, respectively. Based on the total number of workers, farmland (11,894 m2) was the largest for businesses with 4 workers, land (2,770 m2) for those with 5, and plant cultivation area (7,000 m2) for businesses with 2. Total sales of businesses were found to be over 100 million won for ABEs with the largest farmland (12,001 m2), land (1,793 m2), and plant cultivation area (6,763 m2). In terms of sales of agro-healing, ABEs that converted to care farms and were preparing for business, but had no income yet, were found to have the largest farmland (6.977 m2), land (2,496 m2), and plant cultivation area (5,484 m2; Table 8). The draft of the excellent AHF Certification Scheme (RDA, 2023) suggests that not only outdoor spaces (vegetable gardens or yards) but also indoor spaces for learning and activities, breaks, diagnosis and evaluation, and activities in case of rain should be provided. Notably, to provide indoor space, land and buildings must be secured, which seems to be highly likely to arouse complaints from farmers who only have farmland. Nevertheless, since the quality of agro-healing should be controlled with a focus on the consumers who are the recipients of treatment, an appropriate amount of indoor space is to be provided. In addition, it should not be a simple indoor space, but a building fit for its purpose built on the land without any illegal elements in carrying out activities indoors. Furthermore, stable operation should be sought, including systematically managing equipment and tools for service provision; providing therapeutic space and amenities for participants in such services; ensuring safety through safety equipment and management; and eliminating factors that may lead to complaints about the operating facilities.

For quality control to certify excellent Agro-Healing facilities (AHFs) that meet the needs of the times along with the increasing demand for agro-healing, this study aimed to determine the operational status of ABEs in South Korea related to design and business models of care farms. A non-face-to-face online survey was conducted through Company B, a professional research agency, from October to November 2022, targeting 170 ABEs operating care farms nationwide. The survey results are as follows.

First, for regions where care farms were operated, Gyeonggi-do had the largest number (29 respondents, 17.1%). The majority of care farms surveyed started between 2011, when agro-healing began to be studied, and 2020: 107 businesses (62.9%). The most common type of business was individually-run business, at 118 farms (69.4%), and farms whose representatives were farmers were the majority, at 165 (97.1%). For total sales of business and the sales of agro-healing, the largest groups were 30 to less than 100 million won (57 farms, 33.5%) and 10 to less than 30 million won (46 farms, 27.1%), respectively. ABEs, which operate care farms, are management bodies with management and manpower capabilities to systematically provide agro-healing services. They should secure the trust of the public who use the service by having a suitable environment along with at least one program and a business registration number.

Second, in terms of manpower by employment type at care farms, there were more male representatives (92, 54.1%) than female representatives, and their average age was 56.94 ┬▒ 9.88. Businesses with one full-time worker were the largest group at 63 (37.1%). Those without temporary and daily workers, field instructors and volunteers, or unpaid family workers accounted for the majority at 106 (62.4%), 159 (93.5%), and 83 (48.85%), respectively. Businesses with a total of 2 employees were the largest group at 61 (35.9%). In terms of the qualification standards for representatives and employed personnel, the number of personnel who completed agro-healing training courses was 152 (89.4%), and most of them understood agro-healing. However, only 71 (41.8%) out of 170 businesses had personnel with relevant qualifications, including nationally qualified agro-healing specialists and social workers, and privately qualified horticultural therapists and vocational rehabilitation specialists, which was somewhat insufficient. In addition, 89 businesses, or 52.4% of respondents, were utilizing external manpower. An Žć2 test was performed for the status of care farm manpower and verified the goodness-of-fit. Therefore, to enhance the expertise of agro-healing specialist certificate holders and maintain healing farms, it seems that measures to expand the professional training and support system for operating personnel should be explored, including completion of training courses for AHF operators or agro-healing specialists.

Third, in terms of agro-healing facilities and environments, the responses to a multiple-choice question about the priority of plants as a therapeutic resource were analyzed. As cultivation through the program was led to sales revenue, the most frequently planted plant was sweet potatoes, and the least planted was plum. Disregarding sales revenue, sweet potatoes were also the most commonly used plant in agro-healing programs (22 businesses, 16.3%). Of the plants frequently used in the programs, herbs were the most used for therapeutic function (20 businesses, 23.5%). The most common source of information on plants used in the programs was websites on the internet (90 businesses, 27.4%), while the most common criteria for selecting plants used were responses from program participants (104 business, 31.8%). In terms of land ownership of AHFs, private ownership was the majority at 141 business (82.9%), and the average land area was 123,626.05 m2 for farmland, 178,195.98 m2 for land, and 62,511.51 m2 for plant cultivation area. DuncanŌĆÖs multiple range test performed as a post hoc test showed no statistically significant difference between land ownership and area. As recent research has advocated the expansion of gardens to various environments and communities, it seems necessary to specialize agro-healing as an approach to addressing social problems occurring in cities and rural areas in consideration of local environments and diversity. To provide agro-healing programs as a service, specific and detailed standards for appropriate facilities should be established as soon as possible.

With increasing public interest in agro-healing, the proliferation of self-proclaimed ŌĆ£care farmsŌĆØ has raised concerns about the quality of healing farming services and the need to regulate such businesses. In addition, an amendment to the law to introduce a care farm certification scheme was proposed in December 2022 and is scheduled to be implemented from the end of June 2024. Accordingly, there is a need to provide correct information to the public and build trust by selecting excellent facilities from among AHFs that have provided existing services. This study has limitations in that it did not identify the status of differentiated agro-healing programs among the main elements of certification criteria for excellent AHFs for the provision of services by ABEs, which include program composition and content based on the characteristics of service consumers, and effectiveness and operation evaluation. Nevertheless, this study has significance in that it suggests a direction for quality management based on the AHF certification standards (draft). It is expected that it will provide useful basic data for establishing care farm business models and seeking direction in line with the AHF certification scheme in the future.

Table┬Ā1

Organization of survey items

| Survey No. | Factor | Item | Contentsz | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 ŌĆō V5 | Management characteristics | 1. Start year of agro-healing business | cy1(Before the 2,000), cy2(2001ŌĆō2010), cy3(2011ŌĆō2020), cy4(After 2021) |

Yoo et al.(2021b) Jeong et al.(2017) |

| 2. Business type | cb1(Individual business), cb2(Incorporated company), cb3(Non-incorporated company), cb4(Unimcorporated organization), cb5(Others) | |||

| 3. Representative of care farms | cr1(Farmers), cr2(Non-farmers) | |||

| 4. Total sales of business | ct1(Less than 30 million won), ct2(30 to less than 100 million won), ct3(100 million won or More), ct4(No income), ct5(Others) | |||

| 5. Sales of agro-healing | cs1(Less than 10 million won), cs2(10 to less than 30 million won), cs3(30 million won or More), cs4(No income), cs5(Others) | |||

| V6 ŌĆō V11 | Care farm manpower | 6. Management characteristics | Gender, Age | Yoo et al.(2021b) |

| 7. Number of full-time workers | mf1(1 person), mf2(2 people), mf3(3 to 5 people), mf4(6 to 10 people), mf5(None) | |||

| 8. Number of field instructors and volunteers | mv1(1 person), mv2(2 people), mv3(3 people), mv4(4 people), mv5(None) | |||

| 9. Number of temporary and daily workers | mt1(1 person), mt2(2 people), mt3(3 to 5 people), mt4(6 to 10 people), mt5(None) | |||

| 10. Number of unpaid family workers | mu1(1 person), mu2(2 people), mu3(3 people), mu4(4 people), mu5(5 to 7 people), mu6(None) | |||

| 11. Certification status | - | |||

| V12 - V18 | Care farm plant resources | 12. Plants mainly planted | pp1(Vegetables), pp2(Flowers), pp3(Fruit trees and landscaping), pp4(Special purpose and edible plants), pp5(Herbs) | Yoo et al.(2021a) |

| 13. Growing profit plants | ||||

| 14. Program utilization revenue plant | ||||

| 15. Program utilization | ||||

| 16. Healing functional plants | ||||

| 17. Plant information sources | pi1(Acquaintances who run care farms), pi2(Searching websites on the Internet), pi3(RDA), pi4(Regional Agricultural Research Services & Agricultural Technology Center), pi5(Professional books), pi6(Others) | |||

| 18. Plant selection criteria | ps(Degree of therapeutic function), ps2(Ease of initial cultivation[labor, time]), ps3(Ease of continuous management[pests]), ps4(Less cost), ps5(Participant response), ps6(Others) | |||

| V10V11 | Care farm land use | 19. Land ownership status | lo1(Individuals), lo2(Corporations), lo3(Rentals), lo4(Others) |

Yoo et al.(2021b) Jeong et al.(2017) |

| 20. Land area | la1(Farmland), la2(Land), la3(Plant cultivation) |

Table┬Ā2

Management characteristics of agricultural business entities (ABEs) operating care farms in this study

| Item/Contentsz | n (%) | Žć2 | p | Item/Contentsz | n (%) | Žć2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Starting year of agro-healing | ||||||

| ŌĆāSeoul | 1 (0.6) | 57.247 | .000*** | ŌĆācy1 | 1 (0.6) | 244.353 | .000*** |

| ŌĆāMetropolitan City | 8 (4.7) | ŌĆācy2 | 9 (5.3) | ||||

| ŌĆāGyeonggi-do | 29 (17.1) | ŌĆācy3 | 107 (62.9) | ||||

| ŌĆāGangwon-do | 16 (9.4) | ŌĆācy4 | 53 (31.2) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāChungcheongbuk-do | 12 (7.1) | ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāChungcheongnam-do | 26 (15.3) | Representatives of care farms | |||||

| ŌĆāJeollabuk-do | 25 (14.7) | ŌĆācr1 | 165 (97.1) | 150.588 | .000*** | ||

| ŌĆāJeollanam-do | 13 (7.6) | ŌĆācr2 | 5 (2.9) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāGyeongsangbuk-do | 12 (7.1) | ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāGyeongsangnam-do | 24 (14.1) | Total sales of business | |||||

| ŌĆāJeju Island | 4 (2.4) | ŌĆāct1 | 32 (18.8) | 57.471 | .000*** | ||

| ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ŌĆāct2 | 57 (33.5) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ŌĆāct3 | 55 (32.4) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| Business type | ŌĆāct4 | 20 (11.8) | |||||

| ŌĆācb1 | 118(69.4) | 294.882 | .000*** | ŌĆāct5 | 6 (3.5) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆācb2 | 43(25.3) | ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆācb3 | 2(1.2) | Sales of agro-healing | |||||

| ŌĆācb4 | 2(1.2) | ŌĆācs1 | 37 (21.8) | 34.294 | .000*** | ||

| ŌĆācb5 | 5(2.9) | ŌĆācs2 | 46 (27.1) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ŌĆācs3 | 42 (24.7) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆācs4 | 41 (24.1) | ||||||

| ŌĆācs5 | 4 (2.4) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ||||||

Table┬Ā3

Current status of care farm manpower in this study

| Item/Contentsz | t / Žć2 | p | Item/Contentsz | N (%) | Žć2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Gender | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Age (years) | 56.94 (9.88) | 75.143 | .000*** | ŌĆāMale | 92 (54.1) | 1.153 | .283ns |

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāFemale | 78 (45.9) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| N (%) | ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| Number of full-time workers | Number of field instructors and volunteers | ||||||

| ŌĆāmf1 | 63 (37.1) | 363.506 | .000*** | ŌĆāmv1 | 6 (3.5) | 574.882 | .000*** |

| ŌĆāmf2 | 34 (20.0) | ŌĆāmv2 | 1 (0.6) | ||||

| ŌĆāmf3 | 15 (8.8) | ŌĆāmv3 | 2 (1.2) | ||||

| ŌĆāmf4 | 7 (4.2) | ŌĆāmv4 | 2 (1.2) | ||||

| ŌĆāmf5 | 3 (1.8) | ŌĆāmv5 | 159 (93.5) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāmf6 | 48 (28.2) | ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.1) | Number of unpaid family workers | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| Number of temporary and daily workers | ŌĆāmu1 | 34 (20.0) | 233.365 | .000*** | |||

| ŌĆāmt1 | 20 (11.8) | 476.835 | .000*** | ŌĆāmu2 | 41(24.1) | ||

| ŌĆāmt2 | 22 (12.9) | ŌĆāmu3 | 8 (4.7) | ||||

| ŌĆāmt3 | 13 (7.6) | ŌĆāmu4 | 2 (1.2) | ||||

| ŌĆāmt4 | 9 (5.3) | ŌĆāmu5 | 2 (1.2) | ||||

| ŌĆāmt5 | 106 (62.4) | ŌĆāmu6 | 83 (48.8) | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ŌĆāTotal | 170 (100.0) | ||||

Table┬Ā4

Number of plants frequently used in programs and those used for therapeutic function by care farms

| Plants | Frequently used in programs | Used for therapeutic function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| N | % | Žć2 | p | N | % | Žć2 | p | |

| Sweet potato | 22 | 16.4 | 25.421 | .003** | 12 | 14.3 | 35.597 | .000*** |

| Hot pepper | 12 | 8.9 | 4 | 4.8 | ||||

| Pumpkin | 8 | 6.0 | 5 | 5.9 | ||||

| Herbs | 21 | 15.7 | 20 | 23.8 | ||||

| Potato | 17 | 12.7 | 5 | 5.9 | ||||

| Chrysanthemum | 12 | 8.9 | 9 | 10.7 | ||||

| Plum | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.4 | ||||

| Blueberry | 12 | 8.9 | 9 | 10.6 | ||||

| Lettuce | 13 | 9.7 | 4 | 4.8 | ||||

| Rosemary | 15 | 11.2 | 14 | 16.7 | ||||

Table┬Ā5

Care farm plant utilization status

| Item/Contentz | No. of care farm plant resource (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| pp1 | pp2 | pp3 | pp4 | pp5 | Total | |

| Plants mainly planted | 50 (31.2) | 42 (26.2) | 30 (18.8) | 26 (6.3) | 12 (7.5) | 160 (100.0) |

| Growing profit plants | 41 (28.7) | 33 (23.1) | 29 (20.3) | 26 (18.2) | 14 (9.8) | 143 (100.1) |

| Program utilization revenue plant | 38 (27.7) | 32 (23.4) | 27 (19.7) | 25 (18.3) | 15 (10.9) | 137 (100.0) |

| Program utilization | 47 (30.1) | 39 (25.0) | 28 (18.0) | 24 (15.4) | 18 (11.5) | 156 (100.0) |

| Healing functional plant | 44 (30.3) | 30 (20.7) | 29 (20.0) | 22 (15.2) | 20 (13.8) | 145 (100.0) |

z Contents were derived from Table 1.

Table┬Ā6

Information sources of and selection criteria for plants used in agro-healing program

| Item/Contentz | Frequency (N = 328) | % | Žć2 | p | Item | Frequency (N = 327) | % | Žć2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant information sources | Plant selection criteria | ||||||||

| ŌĆāpi1 | 51 | 15.5 | 193.906 | .000*** | ŌĆāps1 | 100 | 30.6 | 151.294 | .000*** |

| ŌĆāpi2 | 90 | 27.4 | ŌĆāps2 | 49 | 15.0 | ||||

| ŌĆāpi3 | 53 | 16.2 | ŌĆāps3 | 66 | 20.2 | ||||

| ŌĆāpi4 | 81 | 24.7 | ŌĆāps4 | 8 | 2.4 | ||||

| ŌĆāpi5 | 46 | 14.0 | ŌĆāps5 | 104 | 31.8 | ||||

| ŌĆāpi6 | 7 | 2.1 | ŌĆāps6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

Table┬Ā7

Land use status on this study

| Item | Contentsz | N | M ┬▒ SDx | F | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmland | lo1 | 141 | 148,580.67 ┬▒ 1,186,083.32ay | .145 | .933NS |

| lo2 | 17 | 1,861.65 ┬▒ 1,981.34a | |||

| lo3 | 6 | 2,433.33 ┬▒ 1,211.06a | |||

| lo4 | 6 | 3,384.17 ┬▒ 4,534.04a | |||

|

|

|||||

| Land | lo1 | 141 | 214,444.04 ┬▒ 1,447,951.74a | .205 | .893NS |

| lo2 | 17 | 1,493.82 ┬▒ 2,480.91a | |||

| lo3 | 6 | 450.00 ┬▒ 339.12a | |||

| lo4 | 6 | 4,768.50 ┬▒ 6,886.42a | |||

|

|

|||||

| Plant cultivation area | lo1 | 141 | 74,410.58 ┬▒ 841,928.62a | .065 | .978NS |

| lo2 | 17 | 6,699.00 ┬▒ 24,075.78a | |||

| lo3 | 6 | 1,083.33 ┬▒ 872.74a | |||

| lo4 | 6 | 2,447.00 ┬▒ 3,282.11a | |||

z Contents were derived from Table 1.

Table┬Ā8

Land area status according to general characteristics of care farms

| Item | Contentsz | Number of farms | Farmland (m2) | Lands (m2) | Plant cultivation area (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 92 | 7,539 | 1,806 | 4,956 |

| Female | 78 | 4,249 | 1,695 | 2,221 | |

|

|

|||||

| Age | under 50s | 38 | 3,374 | 1,090 | 4,127 |

| 50s | 59 | 5,152 | 1,719 | 3,289 | |

| 60s | 55 | 6,228 | 2,535 | 2,296 | |

| 70s over | 18 | 14,002 | 878 | 8,451 | |

|

|

|||||

| Representatives of care farms | cr1 | 165 | 6,167 | 1,525 | 3,783 |

| cr2 | 5 | 2,240 | 9,240 | 1,300 | |

|

|

|||||

| Business type | cb1 | 118 | 6,442 | 1,735 | 3,460 |

| cb2 | 43 | 5,814 | 1,890 | 4,790 | |

| cb3 | 2 | 1,000 | 149 | 333 | |

| cb4 | 2 | 500 | 230 | 437 | |

| cb5 | 5 | 2,425 | 2,360 | 2,940 | |

|

|

|||||

| Number of workers | cw1 | 19 | 2,397 | 1,018 | 1,600 |

| cw2 | 59 | 3,049 | 2,251 | 1,827 | |

| cw3 | 41 | 10,230 | 1,163 | 5,284 | |

| cw4 | 17 | 11,894 | 2,196 | 5,435 | |

| cw5 | 8 | 2,543 | 2,770 | 2,188 | |

| cw6 | 24 | 5,816 | 1,600 | 6,251 | |

| cw7 | 2 | 7,500 | 550 | 7,000 | |

|

|

|||||

| Total sales of business | ct1 | 32 | 2,101 | 1,599 | 1,918 |

| ct2 | 57 | 2,585 | 1,051 | 1,457 | |

| ct3 | 55 | 12,001 | 1,793 | 6,763 | |

| ct4 | 20 | 1,313 | 1,000 | 1,199 | |

| ct5 | 6 | 6,250 | 820 | 2,167 | |

|

|

|||||

| Sales of agro-healing | cs1 | 37 | 3,776 | 863 | 1,547 |

| cs2 | 46 | 6,893 | 1,894 | 4,459 | |

| cs3 | 42 | 6,538 | 1,756 | 3,103 | |

| cs4 | 41 | 6,977 | 2,496 | 5,484 | |

| cs5 | 4 | 3,125 | 317 | 2,750 | |

|

|

|||||

| Total | 170 | 6,050 | 1,756 | 3,710 | |

z Contents were derived from Table 1.

References

Bae, S.J., S.J. Kim, D.S. Kim. 2019. Priority analysis of activation policies for agro-healing services. Journal of the Korean Society of Rural Planning. 25(3):089-102.

https://doi.org/10.7851/Ksrp.2019.25.3.089

Bragg, R. 2020. Growing care farming. Annual survey 2020: Full report Thrive, UK:

Dessein, J., B. Bettina. 2010. The economics of green care in agriculture Loughborough, UK: Loughborough University.

Di lacovo, F., D. OŌĆÖConnor. 2009. Supporting policies for social farming in europe. Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas

Gim, G.M., J.H. Moon, S.J. Jeong, S.M. Lee. 2013. Analysis on the present status and characteristics of agrohealing in Korea. Journal of Agricultural Extension & Community Development. 20(4):909-936.

https://doi.org/10.12653/jecd.2013.20.4.0909

Hassink, J. 2002;Combining agricultural production and care for persons with disabilities: a new role of agriculture and farm animals. In: Farming and Rural Systems Research and Extension. Local Identities and Globalisation Fifth IFSA European Symposium; pp 8-11.

Hassink, J., H. Agricola, E.J. Veen, R. Pijpker, S.R. Bruin, H.A.B. van der Meulen, L.B. Plug. 2020. The care farming sector in the netherlands: A reflection on its developments and promising innovations. Sustainability. 12(9):3811-3827.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093811

Hassink J., van Dijk M.. 2006. Farming for health: green-care farming across europe and the united states of america. In: Springer Science and Business Media. 13.

Hine, R., J. Peacock, J.N. Pretty. 2008 Care farming in the UK: evidence and opportunities. Report for the National Care Farming Initiative UK. University of Essex; Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/ElisaMendelsohn/care-farming-in-the-us-evidence-and-opportunities?qid=05da74e3-88el-4ffb-af9f-ccd6d3b73197&v=&b=&from_search=1

.

Hong, I.K., E.H. Yoo, J.W. Moon, S.M. Lee, S.J. Jeong. 2023. Analysis of performance factors according to the operation of care farms. Journal of People, Plants, and Environment. 26(3):247-255.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2023.26.3.247

Jang, H.S., E.H. Yoo, S.J. Jeong, J.S. Kim. 2020. Stress level and physiology changes in the participants due to agro-healing activities. Korean Society for Horticultural Science Technology. 38(supplement II):189.

Jeong, S.J., H.S. Jang, E.H. Yoo, J.S. Kim, G.W. Lee. 2019. The effects of the level of plant growing activity on the subjective health, depression, and human relations of the elderly participating in weekend farms. Journal of the Korean Society of Rural Planning. 25(4):57-64.

https://doi.org/10.7851/KSRP.2019.25.4.057

Jeong, S.J., J. Hassink, G.M. Kim, S.A. Park, S.O. Kim. 2017. Status and actual condition analysis for current operational cases of care farms in south korea. Journal of People, Plants, and Environment. 20(5):421-429.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2017.20.5.421

Kim, T.G., J.N. Heo. 2011. Creation of value-added farming in line with the sixth industry Research Report of Korea Rural Economic Institute. Seoul, Korea:

Lee, S.W., J.Y. Cho, K.W. Kim, E.H. Yoo, Y.S. Jang. 2020. A qualitative study on care farming the field of social welfare. Public Policy Research. 37(2):273-301.

https://doi.org/10.33471/ILA.37.2.11

Park, Y.J. 2019. The research on green healing agriculture impact on life satisfaction and the psychological well-being. Doctoral dissertation. Westminster Graduate School of Theology, Yong-in, Korea.

Parsons, S., D. Wilcox, R. Hine. 2010;What care farming is. In: Paper presented at the 9th European IFSA Symposium; Vienna, Austria.

Roberta, M., R. Francesco, G. Angela, T. Carmelo, E.D. Salomon, D.I. Francesco. 2020. Italian social farming: the network of Coldiretti and Campagna Amica. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 2020(12):5036-5052.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125036

Rural Development Administration. 2023. Opinion gathering meeting to establish certification standards for excellent agro-healing facilities.

Sempik, J., J. Aldridge. 2006. Care farms and care gardens: horticulture as therapy in the UK. Farming for Health. 13:147-161.

https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4541-7_12

Yoo, E.H., J.S. Kim, S.J. Jeong, Y.K. Kang, H.L. Kwon. 2021a. Analysis of programs provided by agro-healing farm in korea: Focusing on agro-healing farms participated in agro-healing development pilot project. Journal of Recreation and Landscape. 15(3):1-12.

https://doi.org/10.51549/JORAL.2021.15.3.001

Yoo, E.H., J.S. Kim, S.J. Jeong, Y.K. Kang, H.L. Kwon. 2021b. Analysis on current status of agro-healing farm business through agro-healing industry classification. Journal of Recreation and Landscape. 15(4):57-68.

https://doi.org/10.51549/JORAL.2021.15.4.057