|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 25(6); 2022 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: There have been an increasing number of migrant women in Korea. However, they are facing many difficulties in terms of language, psychology, poverty and many other things. Moreover, many mental health problems have emerged since COVID-19, to which migrant women have been more vulnerable. Alternatively, parks and green spaces have been a key to recovering mental health. In line with this, long-term management of green spaces has been raised as an issue to help promote peopleŌĆÖs health and empowerment. However, we have little evidence that the issue also conveys the empowerment of migrants and positivity through participation in park and green space management. Therefore, this study aims at 1) understanding migrant womenŌĆÖs perception toward participation in park and green space management, 2) analyzing the correlation between empowerment and place-keeping, and 3) deriving implications.

Methods: To address the objectives, this study conducts 1) a theoretical review of empowerment and place-keeping of migrant women through literature review and 2) a non-face-to-face survey targeting 108 migrant women. The collected data was analyzed using SPSS 26.

Results: The results are as follows: 1) migrant women have highly positive perceptions toward participation in park and green space management, with statistical significance in funding and governance depending on the marital status, and 2) there is a significant correlation between place-keeping and empowerment in role and expression. This means that increasing the role and expression in empowerment can promote more active participation in park and green space management.

Conclusion: In conclusion, in order to improve the empowerment of migrant women, they should be guided to actively participate in park and green space management and provided with the opportunity to participate in policy-making.

Methods: To address the objectives, this study conducts 1) a theoretical review of empowerment and place-keeping of migrant women through literature review and 2) a non-face-to-face survey targeting 108 migrant women. The collected data was analyzed using SPSS 26.

Results: The results are as follows: 1) migrant women have highly positive perceptions toward participation in park and green space management, with statistical significance in funding and governance depending on the marital status, and 2) there is a significant correlation between place-keeping and empowerment in role and expression. This means that increasing the role and expression in empowerment can promote more active participation in park and green space management.

Conclusion: In conclusion, in order to improve the empowerment of migrant women, they should be guided to actively participate in park and green space management and provided with the opportunity to participate in policy-making.

The expansion of globalization was accompanied by the expansion of multicultural society, and there has been a growing interest worldwide in multiple cultures or multiculturalism since this was first introduced in Canada in 1971, which is widespread in not only Western Europe but also Asia (Fleras and Elliott, 2002). The ratio of multicultural families is constantly increasing both in Korea and overseas, and the purpose of overseas migration is also becoming diverse. According to Statistics Korea, the number of foreigners residing in Korea has constantly increased from 1,261,415 in 2010 to 1,899,519 in 2015 and 2,036,075 in 2020. In particular, the number of marriage migrant women is increasing continuously from 187,404 in 2010 to 238,011 in 2015 and 296,329 in 2020 (Statistics Korea, 2021). It is argued that problems and difficulties in the settlement of migrants, especially migrant women, are emerging as social issues along with this increase (Keskin, 2018). In this regard, as Korea is also entering a multiracial and multicultural society, many government departments including the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family are making various efforts at the policy and welfare level for stable life and social integration of migrants. However, despite these policy and welfare efforts, migrants are facing difficulties due to anxiety, tension, and social stereotypes in an unfamiliar environment (Kim, 2021). In particular, the difficulties and stress experienced by migrant women are directly related to the happiness of their families and highly likely to lead to social problems (Park, 2012), but many policies are relatively not reflecting the interest in the individual needs of migrant women (Kim and Choi, 2013). In other words, this shows that mental and social problems related to the settlement of migrant women are emerging. Accordingly, there has been an increasing interest in their successful settlement and quality of life. Empowerment appears to be an important issue as a social and theoretical background for this. Empowerment means overcoming oneŌĆÖs environment and enhancing his or her own competencies (Kim and Choi, 2017). It is confidence in oneŌĆÖs life as well as satisfaction, which may lead to psychological stability and social activity, and thus is ultimately related to improving the quality of life (Kwak et al., 2015). Studies are conducted in Korea on the empowerment of migrant women, but research is mostly limited as the studies verify the mediating effect (Eo and Lee, 2020; Kim et al., 2015), examine practical intervention activities (Song, 2006; Lee, 2010), or explore group programs using art activities (Choi and Oh, 2011). It is difficult to find empirical studies that can help improve empowerment through continuous practical activities or social contribution and accompaniment. Other countries, especially Australia, actively deal with the settlement of migrants with laws such as ŌĆśThe Australian GovernmentŌĆÖs Multicultural Policy Statement 2011ŌĆÖ. Interestingly, solutions are suggested through communities such as ŌĆśThe Community Welcome DeskŌĆÖ, ŌĆśCommunity Capacity BuildingŌĆÖ, and ŌĆśCommunity Leadership NetworkŌĆÖ. Bush and Doyon (2017) revealed that community participation in parks and green spaces plays a positive role in the inclusion of migrants or multicultural families. In other words, as parks and green spaces help recover mental health and are closely related to the quality of life (Park and Miyazaki, 2008), there could be relevance of improving the quality of life through environmental adaptation pursued by empowerment. Furthermore, the issue of long-term management is raised with the recent increase of qualitative interest in parks and green spaces (Nam and Oh, 2021; Sim and Zoh, 2016; Nam and Dempsey, 2019a). Their studies argue that long-term management of parks and green spaces guarantee the maintenance of quality, and parks and green spaces have a positive effect on mental health. Moreover, they introduced the concept of long-term management through theories such as place-keeping and argued that positivity toward mental health is shared through participation in park and green space management. However, since empowerment appears differently depending on the countryŌĆÖs culture (Eylon and Au, 1999), it is necessary to first understand the empowerment of migrant women today. Moreover, it is difficult to find studies related to migrant womenŌĆÖs participation in park and green space management. This essential understanding must be preceded, followed by an understanding of the correlation between empowerment and participation in park management that has not been addressed in previous studies.

Therefore, this study sets the following research objectives. First, we will examine the perception of empowerment and participation in park and green space management among migrant women. Second, we will analyze the correlation between empowerment and participation in park and green space management. Third, we will provide implications for improvement of empowerment and sustainable management of parks and green spaces based on the study results.

Empowerment is derived from power and refers to granting authority or power and giving ability. In terms of dictionary definition, this concept is related to how much one can control the environment (Yoon, 1999). Empowerment is the acquisition of control over oneŌĆÖs life by increasing oneŌĆÖs personal, interpersonal, and political power in the environment, including both process and outcome. Empowerment in the context of social welfare policy is the ability of an individual or community to understand social, economic, and political forces for the purpose of improving living conditions and to exert influence on the decision-making and implementation of policies related to social welfare by increasing control over these external environments (Jung et al., 2007). In the context of social welfare policy, a correlation is found between community and empowerment. The community is evaluated in relation to the establishment and achievement of goals in the community. A good community from the perspective of social welfare practice refers to a community with the capacity to solve problems. Empowerment is an important requirement for community welfare in that it establishes a decision-making structure that will be supported by all members of the community and increase the participation of the underprivileged in the overall process of community welfare practice (clarifying the problems, investigating the needs, implementing and evaluating strategies) (Paik et al., 2015). Empowerment in the context of community welfare is classified into ŌæĀ participation, ŌæĪ leadership, Ōæó organizational structure, ŌæŻ problem assessment, Ōæż resource mobilization, Ōæź awareness of the problem, Ōæ” partnership, and Ōæ¦ support from external organizations. In particular, empowerment begins as individual members of the community participate in a certain group or organization (Jung et al.,2007). The hierarchy of participation is explained by the ladder of participation by Arnstein (1969), and most governments or organizations think that methods like nominal participation are effective. However, the most effective way to achieve empowerment is to develop individual competencies and improve confidence and responsibility through partnerships involving nonprofit organizations or activities (Arnstein, 1969; Watt et al., 2000; Zimmerman, 2000). Previous studies on empowerment suggest that empowerment is one of the concepts that are considered important as a strength for the vulnerable groups such as the elderly, youth, and disabled (Kim and Choi, 2013). Recently, studies on womenŌĆÖs empowerment are also being actively conducted, many of which are related to practical intervention activities with focus on maximizing self-determination and competencies as the subject of change such as financial difficulties, parenting difficulties, psychological and emotional difficulties, and social prejudice mostly faced by single mothers (Song, 2006; Lee, 2010). Studies were conducted on the relevance between cultural adaptation and empowerment of marriage migrants (Jung, 2009), group programs using art activities for the empowerment of marriage migrant women (Choi and Oh, 2011), and effects of perceived health status, perceived disability, and cultural adaptation on the empowerment of marriage migrant women (Eo and Lee, 2020). However, even these studies on the empowerment of migrant women lack the perception of the use of and participation in parks and green spaces that recently emerge as an issue. Moreover, as parks and green spaces have a positive effect on mental health, partnership participation that is an effective method of empowerment in parks and green spaces will create a synergy in improving the empowerment of migrant women.

The place-keeping theory is to maintain and enhance the value of a place through long-term management to ensure social, environmental, and economic qualities and benefits to be provided to future generations (Wild et al., 2008). This can be applied to management of public places, parks, and green spaces from a long-term view (Dempsey and Burton, 2012). This theory uses an analytic approach through funding, governance, partnership, maintenance, and evaluation to policy-based park management from a long-term perspective (Nam et al., 2019). Policies complexly deal with the interests of overall public management, provide funding, and share responsibilities and information through governance and partnership. This is how the place is managed and evaluated overall and ultimately maintained in the long run. Recently, there are many studies using the concept of place-keeping as a framework of long-term management. Place-keeping is applied to various studies overseas, such as public place management (Dempsey and Burton, 2012), partnership competency evaluation (Alice Mathers et al., 2015), efficient management through partnership (Dempsey et al., 2016a), policy and public service (Dempsey et al., 2016b), long-term prospects of citizens managing urban green spaces (Mattijssen, T.J.M, 2017), park plantation management (Nam and Dempsey, 2019b), practical approach to national health (Nam and Dempsey, 2019a), and public green management of local governments in Norway (Claudia Fongar et al., 2019). Studies in Korea include strategies to create and manage urban parks (Sim and Zoh, 2016), park renewal (Nam et al., 2019), fine dust reduction (Nam and Kim, 2019), evaluation and use of parks and green spaces (Cho and Nam, 2022), and analytical framework for landscape management in islands (Nam and Oh, 2021). This recent long-term management applying the concept of place-keeping have a positive effect on migrant women as the potential subject of management, which raises the need to first understand their perceptions.

A survey was conducted from August 25 to September 4, 2022. The survey was conducted online targeting the community of migrants in Icheon. Total 116 copies of the questionnaire were collected, and 108 of them were analyzed excluding insincere responses.

The data was analyzed using the statistical package SPSS 26. We conducted frequency analysis to identify the demographic characteristics of participants and factor analysis and reliability analysis to test the reliability of the tool. We also conducted descriptive statistics and one-way ANOVA to analyze the perceptions toward empowerment and participation in park and green space management and correlation analysis to examine the correlation.

We used the tool derived from the study by Kim and Choi (2013) on the development of the tool measuring the empowerment of marriage migrant women to determine empowerment. The tool was comprised of 12 items on intrapersonal empowerment, 16 items on interpersonal empowerment, and 2 items on sociopolitical empowerment (Table 1).

The items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, and CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ of this tool was high at 0.914. The reliability of each factor was as follows. In intrapersonal empowerment, the reliability of self-ability was ╬▒ = 0.799, perception toward group was ╬▒ = 0.731, and self-determination and autonomy was ╬▒ = 0.747. In interpersonal empowerment, the reliability of perceiving and autonomy was ╬▒ = 0.738 and role and expression was ╬▒ = 0.903. In sociopolitical empowerment, the reliability of leadership ability was ╬▒ = 0.718.

Through previous studies on place-keeping, we formed the questionnaire in this study with total 24 items based on the perceptions toward policy, funding, governance, partnership, maintenance, and evaluation and applicability to migrant women (Table 2).

A reliability analysis was conducted after the factor analysis to test the validity of the items (Table 3).

As a result of the factor analysis, there were three factors with the eigenvalue all exceeding 1, explaining 65.55% of total variance. KMO and Bartlett that determine whether the factor analysis data can be used were KMO = 0.912, Žć2 = 2408.274 (df = 278), p < .000, thereby adequate for factor analysis. CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ was extremely high at 0.955. By factor, the reliability in funding, governance, and partnership was ╬▒ = 0.938, that in management and evaluation was ╬▒ = 0.941, and that in policy was ╬▒ = 0.728. Item 4 in partnership turned out to be closer to maintenance than partnership, and thus was included in maintenance and evaluation. Moreover, Item 1 of maintenance was about whether to participate in maintenance, which was closer to participation, and thus was included in funding, governance, and partnership.

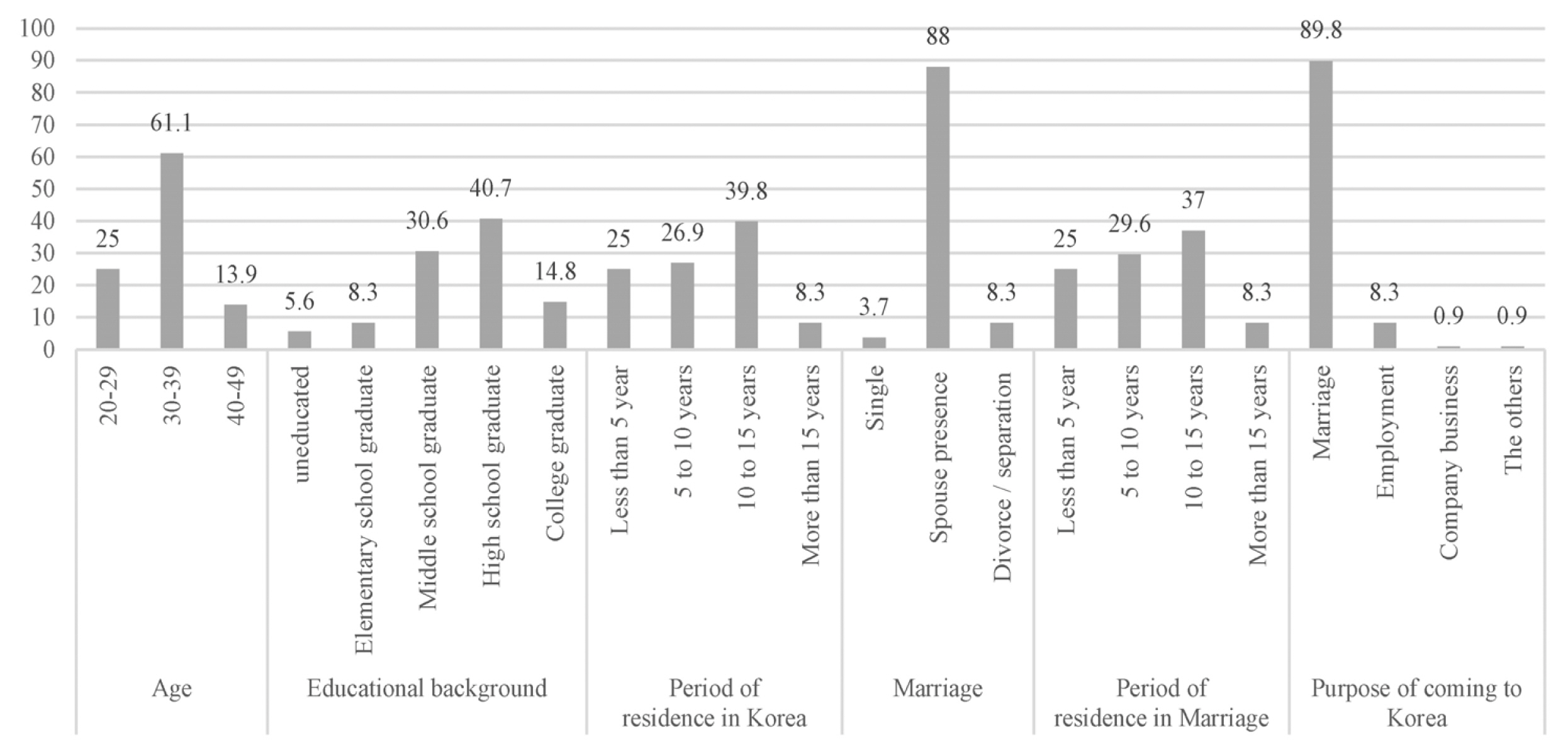

As a result of conducting a frequency analysis to examine the demographic characteristics of participants, it was found that most were in their 30s (66 participants, 61.1%) (Fig. 1).

For educational background, 44 were high school graduates (40.7%). 43 participants lived in Korea for 10 to 15 years (39.8%), and 95 participants were married (88%). 40 participants were married for 10 to 15 years (37%), and 97 participants said they came to Korea for marriage (89.8%). The results can be summarized as follows.

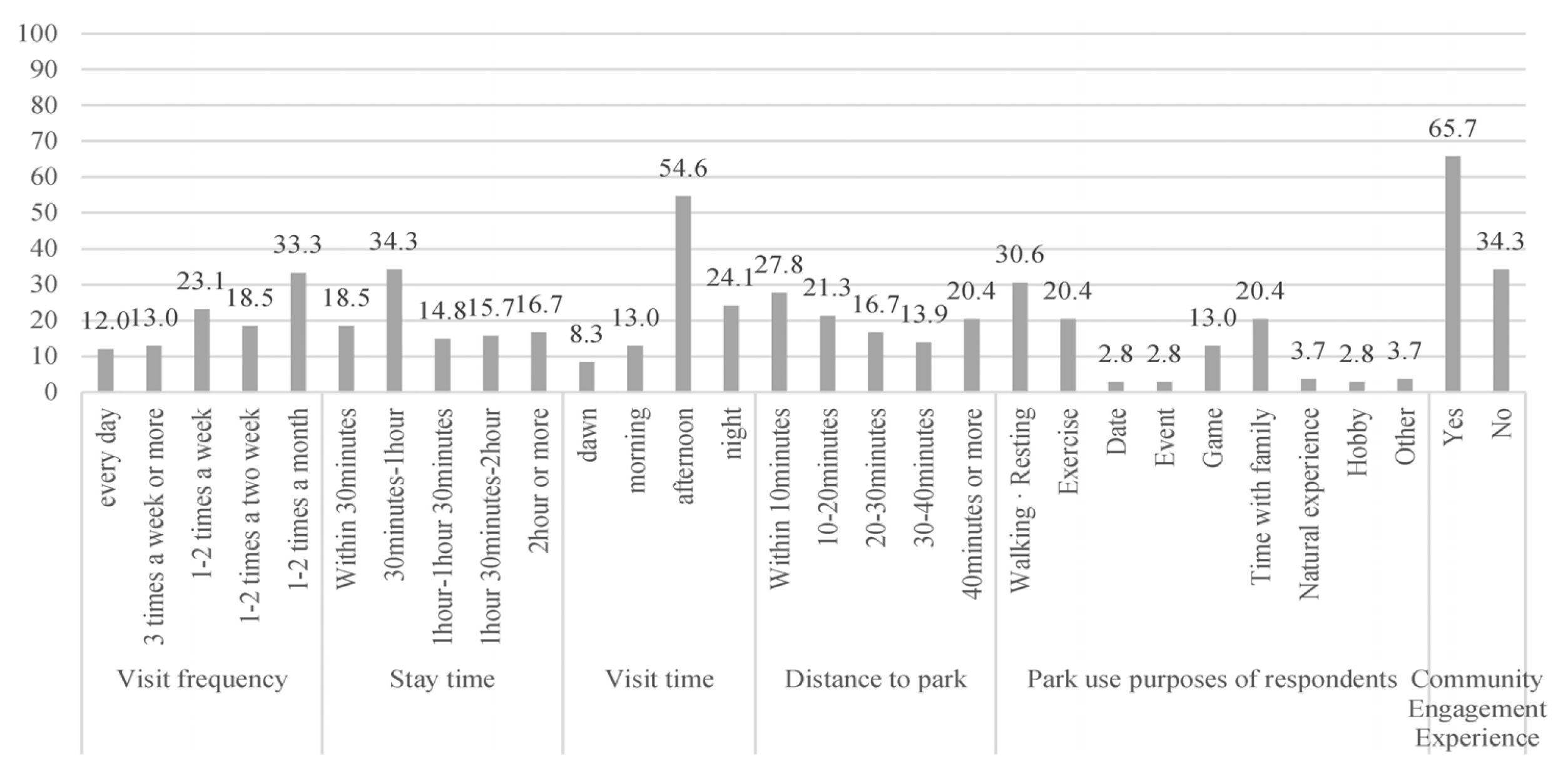

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the park use characteristics of participants (Fig. 2).

The results showed that 36 participants visited the park 1ŌĆō2 times a week (33.3%), 37 participants stayed for 30 minutes to 1 hour (34.3%), and 59 participants visited the park in the afternoon (54.6%). 30 participants claimed that it took less than 10 minutes to get to the park (27.8%), followed by 22 participants who said it took more than 40 minutes (20.4%), indicating the park was not so accessible. 33 participants said they went to the park to walk and rest (30.6%), and 71 participants claimed they have experience in community engagement (65.7%). Most migrant women were visiting the park to rest and staying there for about 30 minutes in the afternoon after work.

Descriptive statistics were used on each item was conducted to examine the perceptions toward empowerment of migrant women and participation in park and green space management. One-way ANOVA was used to test whether demographic characteristics affect participation in park and green space management. The results are as follows.

As a result of descriptive statistics to examine the empowerment of migrant women, role and expression showed the highest score (4.4459), followed by perception toward group (4.2870), self-ability (4.2241), self-determination and autonomy (4.0625), perceiving and autonomy (3.8364), and leadership ability (3.0694) (Table 4).

In particular, the scores were highest for experience sharing (A25) at 4.6296 and value of life (A18) at 4.5833. On the other hand, in leadership ability, the scores were lower for group representative (A29) at 3.0278 and problem solving (A30) at 3.1111 compared to other items.

As a result of descriptive statistics of place-keeping to examine migrant womenŌĆÖs participation in park and green space management, budget/governance/partnership showed the highest score at 4.0042, followed by policy at 3.9722, and management/evaluation at 3.6451 (Table 5).

More specifically, policy 4 was the highest (4.2037), followed by management 1(4.1481), policy 3(4.1389), and policy 2 (4.1296). In other words, migrant women were showing much interest in policies.

As a result of analyzing the difference in basic perceptions depending on demographics, it was found that the difference was statistically significant depending on marital status, and meaningful results were derived in items such as funding and management participation.

As a result of one-way ANOVA in the perception toward funding in the public sector depending on marital status, the mean was 2.75 for single, 3.9789 for spouse present, and 4.333 for divorced/separated, showing significance at 0.010. This indicates that there was a difference in perception toward funding in the public sector depending on marital status. The posttest results showed that there was a difference in single-spouse present and single-divorced/separated within the significance level of 0.05. In other words, participants with a spouse or participants that are divorced/ separated tended to think more positively toward funding in the public sector compared to singles. As for perceptions toward funding in the private sector depending on marital status, the mean was 2.25 for single, 3.6316 for spouse present, and 3.8889 for divorced/separated. The results of one-way ANOVA showed that the p-value was 0.888, all exceeding 0.05 and thereby homogeneous. The results of one-way ANOVA showed that the p-value was 0.028 and thereby significant. The posttest results showed that there was a difference in single-spouse present and single-divorced/separated within the significance level of 0.05. In other words, participants with a spouse or participants that are divorced/separated tended to think more positively toward funding in the private sector compared to singles.

As for marital status and intention to participate in management, the mean was 2.75 for single, 4.1895 for spouse present, and 4.333 for divorced/separated. As a result of one-way ANOVA, the p-value was 0.165, all exceeding 0.05. This is proved by the samples that can be used to conduct analysis of variance between groups. The results of one-way ANOVA showed that the p-value was 0.014 and thereby significant. The posttest results showed that there was a difference in single-spouse present and single-divorced/separated within the significance level of 0.05. In other words, participants with a spouse or participants that are divorced/separated tended to think more positively toward management participation compared to singles.

As a result of analyzing the correlation between the empowerment of migrant women and place-keeping, it was found that role and expression showed significance with place-keeping in empowerment, and all items except partnership (management) in self-ability also showed significance (Tables 6 and 7).

In other words, higher role and expression and self-ability in empowerment led to higher perception toward participation in park and green space management, showing a close positive correlation. In particular, for policy, all items showed significance except policy assistance-leadership ability and policy understanding-perception toward group. The correlation was strongest between the intention to participate in policy making and role and expression (R = 0.554) and between the intention to participate in policy making and self-ability (R = 0.507).

For funding, partnership, and governance, perceiving and autonomy and leadership ability of empowerment only showed a correlation with community participation and park management of a private community. They show ed a positive correlation, and even though the correlation is weak, community participation and park management of a private community may have a positive effect on perceiving and autonomy as well as leadership ability of migrant women.

The following social and policy implications can be derived from the results of this study.

First, socially, there is a need to promote empowerment by activating migrant womenŌĆÖs participation in the park management community. The results of this study show that role and expression in empowerment were significant along with participation in park and green space management, and all items except one in self-ability showed significant results. Moreover, regarding park use characteristics, most migrant women responded that they have participated in the community (71 participants/65.7%). Not all communities in which migrant women are participating are related to parks, but the participants had a positive perception toward community participation and activities. For migrant women, community activities help increase social communication and reduce stress caused by cultural differences (Ley and Murphy, 2001; Morey et al., 2020). Moreover, participation in park and green space management through the community can be regarded as migrant womenŌĆÖs social participation. Seo and Im (2018) stated that migrant women can interact with others through social participation, acknowledge themselves, and improve the quality of their lives. Furthermore, Gilbert and Ward (1984) argued that community participation of migrants helps them settle into a new culture and achieve psychological improvement. In fact, many countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia are actively promoting communities related to parks and gardens for a strong sense of community so that migrants can settle in a multicultural society (Egerer et al., 2019).

Second, it is necessary to provide policies related to support of community participation programs based on migrantsŌĆÖ decision-making participation in terms of policy. In this study, it was found that migrant women had a high interest in policies and had a strong positive correlation with empowerment. This shows that migrant women were active about policy participation. Settling into a new culture through active policy participation of migrants is attempted in various ways according to the ŌĆśEthical Decision Making ModelŌĆÖ by Frame and Williams (2011), which helps migrants understand other cultures and help them settle through policy participation, as well as the counseling support by Parker and Lee (2021) to increase participation of migrants in decision making. By comparison, the multicultural policy in Korea has issues such as an inadequate business system, reckless one-time projects, and unclear goals. There is also insufficient social consensus and agreement about migrants (Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2011), which is why matters regarding the opportunity for migrants to participate in decision making seem passive. The increased opportunity to participate in decision making through various programs and promotion of participation in communities related to parks and green spaces in Australia convey the significance of multicultural inclusion. Bush and Doyon (2017) proved in their study that participation in communities related to parks and green spaces plays a positive role in inclusion of migrants and multiple cultures. This implies that creating a sustainable community through policy improvement and future policy participation of the community will play a positive role in migrants and multicultural inclusion.

This study aimed to understand the perceptions toward empowerment and participation in park and green space management among migrant women and examine the correlations, based on which it intended to provide implications to promote empowerment and sustainable management of parks and green spaces. Accordingly, the following results were derived. First, empowerment was highest in role and expression, followed by perception toward group, self-ability, self-determination and autonomy, perceiving and autonomy, and leadership ability. Participation in park and green space management was highest in budget/ governance/partnership, followed by policy and management/ evaluation. This shows that migrant women are highly interested in taking a role and expressing their opinions and are enthusiastic about participating in communities for park and green space management. Second, as a result of correlation analysis, role and expression in empowerment showed a significant correlation with participation in park and green space management. Moreover, in self-ability, all items except one showed significant results. In other words, participation in park and green space management may have a positive effect on improving the empowerment of migrant women. Furthermore, migrant womenŌĆÖs participation may have a positive effect on activation of parks and green spaces. Accordingly, this study provided the following implications: the need to improve empowerment by socially promoting migrant womenŌĆÖs participation in park management communities and to improve policies related to support of community participation programs based on migrantsŌĆÖ participation in policy decision making. In conclusion, understanding the correlation between migrant womenŌĆÖs empowerment and participation in park and green space management may lead to improved empowerment when there are policy implications to improve social consensus for migrant women to participate in communities for park and green space management and improvement plans for community participation.

Table┬Ā1

Empowerment reliability analysis with questions

Table┬Ā2

Reliability analysis on place-keeping

| place-keeping | Number of Questions(24) | CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Funding, Governance, Partnership | 11 Questions | 0.938 | |

| Evaluation, Maintenance | 9 Questions | 0.941 | 0.955 |

| Policy | 3 Questions | 0.728 | |

Table┬Ā3

Factor analysis on place-keeping

Table┬Ā4

Descriptive statistics of empowerment

Table┬Ā5

Descriptive statistics of place-keeping

Table┬Ā6

Correlations of empowerment variables with funding ┬Ę governance ┬Ę partnership

| Funding ┬Ę Governance ┬Ę Partnership | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| G1 | P1 | G3 | M1 | F2 | Po4 | F1 | G4 | P3 | G2 | P2 | |

| Self-ability | 0.342 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.239 | 0.328 ** | 0.432 ** | 0.271 ** |

| Perception toward group | 0.199 | 0.159 | 0.177 | 0.136 | 0.149 | 0.352 ** | 0.098 | 0.179 | 0.204 | 0.224 | 0.136 |

| Self-determination and autonomy | 0.183 | 0.083 | 0.123 | 0.117 | 0.118 | 0.259 ** | 0.048 | 0.046 | 0.069 | 0.157 | 0.058 |

| Perceive and autonomy | 0.203 | 0.171 | 0.244 | 0.161 | 0.225 | 0.247 | 0.153 | 0.159 | 0.258** | 0.269 ** | 0.160 |

| Role and expression | 0.378 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.437 ** | 0.251 ** |

| Leadership ability | 0.082 | 0.116 | 0.157 | 0.098 | 0.105 | 0.115 | 0.066 | 0.229 | 0.250** | 0.270 ** | 0.227 |

Table┬Ā7

Correlations of empowerment variables with evaluation ┬Ę maintenance and policy

| Evaluation ┬Ę Maintenance | Policy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| M6 | Po2 | Po1 | Po3 | M7 | M1 | E1 | P4 | E2 | Po2 | Po1 | Po3 | |

| Self-ability | 0.350 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.158 | 0.262 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.507 ** |

| Perception toward group | 0.243 | 0.289 ** | 0.166 | 0.374 ** | 0.155 | 0.117 | 0.201 | 0.078 | 0.227 | 0.289 ** | 0.166 | 0.374 ** |

| Self-determination and autonomy | 0.093 | 0.314 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.149 | 0.074 | 0.089 | 0.080 | ŌłÆ0.003 | 0.314 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.326 ** |

| Perceive and autonomy | 0.137 | 0.382 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.380 ** | 0.206 | 0.186 | 0.267 ** | 0.266 ** | 0.133 | 0.382 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.380 ** |

| Role and expression | 0.356 ** | 0.466 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.554 ** | 0.338 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.266 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.466 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.554 ** |

| Leadership ability | 0.358 ** | 0.244 | 0.458 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.478 ** | 0.128 | 0.244 | 0.458 ** | 0.302** |

References

Arnstein, SR 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners. 35(4):216-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Bush, J, A Doyon. 2017;Urban green spaces in Australian cities: social inclusion and community participation. In: 8th State of Australian Cities National Conference; 28ŌĆō30 November 2017; Adelaide, Australia. https://doi.org/10.4225/50/5b2dd24975904.

Choi, JS, JY Oh. 2011. A study on group art activity program for empowerment of the female marriage immigrants. Korean Journal of Family Social Work. 33:319-348. https://doi.org/10.16975/kjfsw.2011..33.011

Choi, SA, YS Oh. 2021. Exploring research trends on the mental health of marriage immigrant women. Contemporary Society and Multiculture. 38:273-300. https://doi.org/10.15400/mccs.2021.12.38.273

Dempsey, N, M Burton. 2012. Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 11(1):11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2011.09.005

Dempsey, N, M Burton, R Duncan. 2016a. Evaluating the effectiveness of a cross-sector partnership for green space management: The case of Southey Owlerton, Sheffield, UK. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 15:155-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.12.002

Dempsey, N, M Burton, J Selin. 2016b. Contracting out parks and roads maintenance in England. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 29(5):441-456. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-02-2016-0029

Egerer, M, C Ord├│├▒ez, BB Line, D Kendal. 2019. Multicultural gardeners and park users benefit from and attach diverse values to urban nature spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 46:126445.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126445

Eo, YS, YH Lee. 2020. Influence of perceived health status, perceived barrier, cultural acculturation on empowerment in married migrant women. The Korea Society for Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education. 32(5):1308-1320. https://doi.org/10.13000/JFMSE.2020.10.32.5.1308

Eylon, D, KY Au. 1999. Exploring empowerment cross-cultural differences along the power distance dimension. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 23(3):373-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(99)00002-4

Fleras, A, JL Elliott. 2002. Engaging diversity: Multiculturalism in Canada (2nd ed.). Toronto: Nelson Thomson Learning.

Fongar, TB, B Randrup, B Wistrom, I Solfjeld. 2019. Public urban green space management in Norwegian municipalities: A managersŌĆÖ perspective on place-keeping. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 44:126438.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126438

Frame, MW, CB Williams. 2011. A model of ethical decision making from a multicultural perspective. Counceling and Values. 49(3):165-179. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2005.tb01020.x

Gilbert, A, P Ward. 1984. Community participation in upgrading irregular settlements: The community response. World Development. 12(9):913-922. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(84)90048-2

Jiang, SJ 2018. Research on urban park design principles and elements in sustainable development-focusing on shanghai Houtan park in China. MasterŌĆÖs thesis. Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea.

Jung, MH 2009. A study on factors affecting of the empowerment in married female immigrants. Doctoral dissertation. Pyeongtaek University, gyeonggi-do, Korea.

Jung, SD, GM Kim, SO Park, HW Park, HJ Choi, HA Lee. 2007. Empowerment in social work Seoul, Korea: Hakjisa.

Keskin, SC 2018. Problems and their solutions in a multicultural environment according to pre-service social studies teachers. Journal of Education and Training Studies. 6(7):138-149. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i7.3292

Kim, AN, SA Choi. 2013. Development and validation of the empowerment scale for marriage immigrant women. Journal of Korean WomenŌĆÖs Studies. 29(2):189-229.

Kim, AN, SA Choi. 2017. Factors affecting the life satisfaction of foreign workers in korea: focusing on educational mismatch, discrimination and empowerment. Korean Journal of Social Welfare Studies. 48(2):331-357. https://doi.org/10.16999/kasws.2017.48.2.331

Kim, J, JG Lee, YS Kim. 2015. Effect of social support and self-efficacy on empowerment of marriage immigrant women in Korea. Journal of Social Science. 41(2):79-103.

Kim, JS 2021. Transnational subjects and the covid-19 pandemic: the workings of raciolinguistic ideologies on international studentsŌĆÖ identity and agency. Contemporary Society and Multiculture. 11(2):69-102. http://doi.org/10.35281/cms.2021.05.11.2.69

Kim, WJ, CH Lee, JS Sung. 2018. A study on the activation factors of voluntary community activities in neighborhood parks - based on the people who love chamsaem in Sejong City-. Journal of the Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture. 46(2):37-51. https://doi.org/10.9715/KILA.2018.46.2.037

Kim, YG 2014. A Study on the distributive equity of neighborhood urban park in Seoul viewed from green welfare. Journal of the Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture. 42(3):76-89. https://doi.org/10.9715/KILA.2014.42.3.076

Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2011 A study on the current status of multicultural policies and policy improvements in Korea (Report No.2011-37) Seoul, Korea. Author; Retrieved from www.kipa.re.kr.

Kwak, MJ, SS Koo, HM Kim. 2015. Acculturation stress of multicultural women impact on quality of life: Empowerment as a parameter. Korean policy sciences review. 19(4):133-161.

Lee, IS 2010. The effect of single mothersŌĆÖ community participation on empowerment -Focused on the mediation effect of gender consciousness. Korean Journal of Social Welfare Studies. 41(2):189-216. https://doi.org/10.16999/kasws.2010.41.2.189

Ley, D, P Murphy. 2001. Immigration in gateway cities: Sydney and Vancouver in comparative perspective. Progress in Planning. 55(3):119-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(00)00025-8

Li, KY, SB Kim. 2021. The effect of park use characteristics and satisfaction of foreigners in Dalseo-gu, Daegu city on the quality of life. Journal of Recreation and Landscape. 15(3):33-42. http://doi.org/10.51549/JORAL.2021.15.3.033

Mathers, A, N Dempsey, JF Molin. 2015. Place-keeping in action: Evaluating the capacity of green space partnerships in England. Landscape and Urban Planning. 139:126-136. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.03.004

Mattijssen, TJM, APN van der Jagt, AE Buijs, BHM Elands, S Erlwein, R Lafortezza. 2017. The long-term prospects of citizens managing urban green space: From place making to place-keeping? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 26:78-84. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.05.015

Morey, BN, GC Gee, S Shariff-Marco, J Yang, L Allen, SL Gomez. 2020. Ethnic enclaves, discrimination, and stress among Asian American women: Differences by nativity and time in the United States. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 26(4):460-471. http://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000322

Nam, J, CS Oh. 2021. Delivering the implication of place-keeping on long-term island landscape management-The case of the policy of the Isle of Wight in the UK-. The Journal of Korean Island. 33(1):247-265. http://doi.org/10.26840/JKI.33.1.247

Nam, J, N Dempsey. 2019a. Place-keeping for health? charting the challenges for urban park management in practice. Sustainability. 11(16):4383.http://doi.org/10.3390/su11164383

Nam, J, N Dempsey. 2019b. Understanding stakeholder perceptions of acceptability and feasibility of formal and informal planting in SheffieldŌĆÖs District Parks. Sustainability. 11(2):360.http://doi.org/10.3390/su11020360

Nam, J, KH Kim. 2019. Exploring community-led particulate matters abatement -The cases of particulate matters abatement community gardens in London, UK-. Journal of Recreation and Landscape. 13(3):39-52. http://doi.org/10.51549/JORAL.2020.13.3.039

Nam, J, NC Kim, DW Kim. 2019. Exploring policy contexts and sustainable management structure for park regeneration-a focus on the case of Green Estate Ltd, Sheffield, UK-. Journal of the Korean Society of Environmental Restoration Technology. 22(4):15-34. https://doi.org/10.13087/kosert.2019.22.4.15

Parker, MM, MA Lee. 2021. Utilizing experiential activities to facilitate multicultural understanding within ethical decision-making. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. 17(4):533-545. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2021.1921645

Paik, JM, JG Kam, CW Kim. 2015. Community welfare theory (pp. 90-91). Paju, Korea: Nanam Publishing.

Park, BJ, Y Miyazaki. 2008. Physiological effects viewing forest landscapes: Results of fields tests in Atsugi city, Japan. Journal of Korean Society of Forest Science. 97(6):634-640.

Park, IK, IC Chung, DW Oh, YR Jung. 2021. Changes in the number of urban park users due to the spread of COVID-19: Time series big data analysis. Journal of the Korean Regional Science Association. 37(2):17-33. https://doi.org/10.22669/krsa.2021.37.2.017

Park, ST 2012. The effects of role burden immigrant married women on quality of life; The application of double ABCX model. Doctoral dissertation. Catholic University of Daegu, Daegu, Korea.

Seo, JB, MH Im. 2018. The structural relationship between social participation, social support, empowerment and quality of life in Vietnamese migrant women in Jeonbuk. Journal of Education for International Understanding. 13(2):157-181. https://doi.org/10.35179/jeiu.2018.13.2.157

Shin, HJ, CR Nho, SH Heo, JH Kim. 2015. A meta-analysis of the variables related with acculturative sress for marriage-based migrant women. Korean Journal of Social Welfare. 67(3):5-29.

Sim, JY, KJ Zoh. 2016. Strategies of large park development and management through governance - Case studies of the presidio and Sydney Harbour national park-. Journal of the Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture. 44(6):60-72. https://doi.org/10.9715/KILA.2016.44.6.060

Song, DY 2006. Psycho-social support program for single mothers with dependent children and alternative empowerment approach. Korean Journal of Family Welfare. 11(1):131-154.

Watt, S, C Higgins, A Kendrick. 2000. Community participation in the development of services: a move towards community empowerment. Community Development Journal. 35(2):120-132.

Wild, TC, S Ogden, DN Lerner. 2008;An innovative partnership response to the management of urban river corridors? SheffieldŌĆÖs river stewardship company. In: 11th international conference on urban drainage; Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. 23 September 2008, 1ŌĆō10.

Yoon, MW 1999. A study on the Empowerment of Social Workers-In Focus of Social Workers Working at Community Welfare Centers. MasterŌĆÖs thesis. Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

Zimmerman, MA 2000. Empowerment theory: psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43-63). New York: Plenum.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 653 View

- 10 Download

- Related articles in J. People Plants Environ.