|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 25(4); 2022 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: This study was conducted to investigate the psychological and emotional effects of gardening activities held on the campus of D University on parents of children with developmental disabilities.

Methods: There were 12 study subjects, including 11 parents of children with developmental disabilities, and 1 grandmother as a primary caregiver. A gardening program was conducted for 30 sessions twice a week over 3 months, from August 21 to November 27, 2021. Gardening activities including gardening practice and plant monitoring were performed in a ‘healing garden’ on the campus of D University, in a program designed to combine activities on the trail and those in an outdoor garden on the campus. Tests were conducted to verify the effects of such activities, including the Parenting Stress Index (K-PSI-4) and Korean-style mental health assessment (MHA) with 5 types of scales (depression, anxiety, daily vitality, quality of life, and mindfulness).

Results: Based on the K-PSI-4 results, the total parenting stress level was decreased from 261.6 points in the pre-test to 241.5 points in the post-test, and notably, the stress level in the Child domain decreased by a significant level, from 120.1 to 109.1 points (p < .05). In the subscale of Acceptability in the Child domain, and the subscale of Isolation in the Parent domain, there were significant changes, from 19.6 to 17.2 points and from 16.2 to 12.6 points, respectively (p < .05). Based on the Korean-style MHA results, there were significant changes in depression, from 3.34 points in the pre-test to 1.24 points in the post-test, and in the daily vitality scale, from 18.25 to 21.38 points (p < .05). In a survey of participants’ satisfaction with the program, all participants answered that their daily stress was relieved, which was the most common response given. This was followed by “acquiring knowledge about plants and gardens” and “maintaining physical health.”

Conclusion: The gardening program had psychological and psychological effects on parents of children with developmental disabilities, including the effects of reducing parenting stress and lowering depression and anxiety. It is expected that gardening programs will play a good role as a support program for persons with disabilities or diseases, as well as for their caregivers and guardians.

Methods: There were 12 study subjects, including 11 parents of children with developmental disabilities, and 1 grandmother as a primary caregiver. A gardening program was conducted for 30 sessions twice a week over 3 months, from August 21 to November 27, 2021. Gardening activities including gardening practice and plant monitoring were performed in a ‘healing garden’ on the campus of D University, in a program designed to combine activities on the trail and those in an outdoor garden on the campus. Tests were conducted to verify the effects of such activities, including the Parenting Stress Index (K-PSI-4) and Korean-style mental health assessment (MHA) with 5 types of scales (depression, anxiety, daily vitality, quality of life, and mindfulness).

Results: Based on the K-PSI-4 results, the total parenting stress level was decreased from 261.6 points in the pre-test to 241.5 points in the post-test, and notably, the stress level in the Child domain decreased by a significant level, from 120.1 to 109.1 points (p < .05). In the subscale of Acceptability in the Child domain, and the subscale of Isolation in the Parent domain, there were significant changes, from 19.6 to 17.2 points and from 16.2 to 12.6 points, respectively (p < .05). Based on the Korean-style MHA results, there were significant changes in depression, from 3.34 points in the pre-test to 1.24 points in the post-test, and in the daily vitality scale, from 18.25 to 21.38 points (p < .05). In a survey of participants’ satisfaction with the program, all participants answered that their daily stress was relieved, which was the most common response given. This was followed by “acquiring knowledge about plants and gardens” and “maintaining physical health.”

Conclusion: The gardening program had psychological and psychological effects on parents of children with developmental disabilities, including the effects of reducing parenting stress and lowering depression and anxiety. It is expected that gardening programs will play a good role as a support program for persons with disabilities or diseases, as well as for their caregivers and guardians.

Based on the registration status of persons with disabilities (PWDs) in South Korea, as of 2020, the number of newly registered PWDs was 83,000, and the total number of PWDs registered was 5.1% of the total population. Notably, among the 15 disability types, the proportion of persons with developmental disabilities such as intellectual disability and autism increased from 7.0% in 2010 to 9.4% in 2020, reaching almost 10% of all disabled people. In particular, of the 75,482 children with disabilities (CWDs) aged 0–17, the proportion of children with developmental disabilities (CDDs) reached 66.9% (Ministry of Health & Welfare, 2020). Developmental disabilities require daily care and support throughout life, and notably, parents taking care of such CWDs have a great burden. The emotional burden on the parents of a CWD was found to be higher than the economic and physical burdens (Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute, 2013). CWDs and their parents and families are in a reciprocal relationship where they influence each other (Kang and Kim, 2012). Relieving the stress of parents nurturing CWDs and providing necessary support services to such parents is as important as education and support for CWDs (Kim, 2010).

A study of in-depth interviews with mothers of CDDs found that they have various difficulties related to nurturing a CWD, and needs for family support (Jeon, 2007), showing emotional difficulties (need for emotional support) and a sense of social alienation (need for improved social awareness) in the psychological aspect. Based on interviews and surveys on the perceptions of the quality of life of parents of CWDs, the level of emotional well-being among the sub-factors of quality of life was lower than that of other factors, which can be said to be the result of insufficient support, including psychological support such as coping with depressive stress; support to help parents get rest, and for activities to enhance the relationship between CWDs and their parents (Kang, 2016). To improve the quality of life of parents nurturing a CDD, it is necessary to provide them with services that help them to step away from the parenting environment and find vitality in life, such as through hobbies, and emotional support to relieve their parenting stress (Cho and Moon, 2016). Of the service policies for the disabled in South Korea, the family empowerment program includes supports for childcare, parental counseling, and family relaxation activities. Childcare support is a service that dispatches caregivers; parent counseling support provides more than 12 psychological counseling sessions over 2–3 months; family relaxation activity support covers family travel or camping expenses (Ministry of Health & Welfare, 2022). Support for parents is mainly provided in the form of education and counseling services (Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 2015). There have been many studies on the need for family support, the psychological and emotional aspects of parents and non-disabled siblings, and the cooperation between such family and experts; parents of children with physical disabilities reported psychological stress, depression, inability to accept their child’s disability, and fears and anxiety about the future. Research to support such emotional aspects, and in particular, experimental studies on various strategies related to family support are needed (Jung et al., 2020).

The positive effects of activities related to plants or nature on human emotions and health have been shown through many studies over a number of years in the field of horticultural therapy, and research is being pursued in new fields such as agri-healing, forest therapy, and garden healing. Studies of gardening and similar activities include: a systematic review of current research on the health benefits of a garden environment (Kang et al., 2020); a study on the effects of a horticultural therapy program focusing on gardening activities (Kim et al., 2020); an analysis of the healing effects of forest therapy and horticultural therapy (Park et al., 2015); community gardening activities and their effects on mental health of residents (Jang et al., 2019). There has also been a study on the effect of garden healing programs on the psychological emotion of the bereaved (Na, 2020). The purpose of this study is to verify the psychological and emotional effects of garden healing. To this end, the effect of gardening activities on the stress and psychology of parents raising children with developmental disabilities was investigated using a healing garden created on a university campus. In addition, it was sought to develop and propose a gardening activity program (GAP) as a social, psychological and emotional support service for CDDs’ parents.

The purpose and experimental method of this study were approved by the Institutional Bioethics Committee of University D in August 2021 (approval number: CUIRB-2021-0031). To recruit subjects, an official recruitment notice was sent to 98 educational institutions related to CDD (Offices of Education, special schools, elementary schools that operate special classes) and 19 welfare institutions for CDD (welfare center, support center) located in D metropolitan city and K, and applications for participation were received online. The subjects were children and their caregivers, which were divided into a child group and a caregiver group, and a preliminary briefing was held only for families who could participate in separate gardening programs. After a full explanation of the purpose and method of the study, a total of 12 subjects were selected, including 11 parents and one grandmother, all of which submitted their consent to participate in the study. A study was conducted on the effect of a GAP on a group of caregivers.

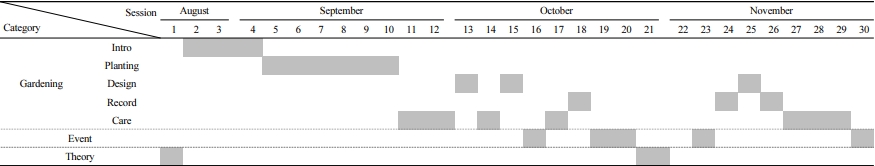

From August 21 to November 27, 2021, a GAP was conducted twice a week for a total of 30 sessions: every Wednesday and Saturday for 3 hours per session. After dividing the space on the D University campus into three zones (healing garden, walking trail (dulle-gil), and resting garden), a GAP was conducted in the healing garden, including horticultural practice and monitoring of garden plants, and the subjects were allowed to take a walk and rest on the trail and resting garden. An expert group consisting of horticultural professors, landscape architects, social workers, and gardening activity experts set an effective program direction and formed detailed program activities. The program was conducted by one main facilitator (a doctorate-level student in horticulture) and two assistant facilitators (a Master of horticultural therapy and a student enrolled in the department of landscape architecture). Each session was divided into the introduction part for 30 minutes (stretching, activity guide, tool usage guide, etc.), the activity execution part for 1 hour 20 minutes (garden activities per session), and the closing part for 40 minutes (finishing and organizing tools, reviewing activities, and walking on campus). Interventions in each of the following four areas were set as the basic direction of the GAP: emotional and psychological support, improvement of physical health, provision of knowledge and educational opportunities, and improvement of social skills. On this basis, the program provided the group with emotional and psychological support through relaxation, contact with nature, and opportunities to immerse in gardening activities; helped improve their physical health through exercise and muscle strengthening; provided knowledge about plants and gardening; and enabled them to interact with other participants and form a bond while participating in the program. The program was divided into gardening, events, and theory. Gardening was carried out in five categories: learning about gardens, planting, garden design, gardening records, and garden maintenance. From the end of August to September, the late summer, the participants learned and practiced about plants and soil in the garden as activities of learning about gardens, and they planted plants and created flower beds for an autumn garden. In October, they designed a container garden themselves, recorded gardening activities such as seed harvesting, and learned about garden maintenance. At the end of November, the program was completed by preparing for the wintering of plants. Events were held in October as a picnic and experiences using garden crops, and also included orientation and theory programs. This study focused on the effects of gardening activities with the arrangement of 77% of the total program for gardening (23 sessions in total), 16% for events (5 sessions), and 7% theory (2 sessions; Table 1).

The detailed activities of the program started with gardening activities to understand healing gardens and plants on the campus, and learn basic knowledge about garden maintenance including soil and fertilizer. In Session 5, the subjects planned a vegetable garden themselves in the planter, and planted vegetable seeds and seedlings. In Sessions 6–8, an autumn flower garden was made in the healing garden and plants were planted. In Sessions 9–10, a hub garden was created using herbs and aromatic plants. In Session 11, sprouts and seedlings of the vegetable garden were managed, and in Session 12, compost was added to the garden to supplement the insufficient nutrition. In Session 13, the subjects learned about container gardens and planted Cyclamen persicum in pots. In Session 14, they mulched the ground around the plants with bark and gravel for garden maintenance, and in Session 15, they designed and made a container garden themselves. In Session 16, a flower basket was made with flowers from the autumn flower garden, and in Session 17, garden maintenance was performed, including removing weeds in the garden. In Session 18, the seeds of garden plants were harvested, recorded and stored. In Session 19, smudge sticks were made using herb plants from the herb garden. In Session 20, an autumn garden picnic event was held for participants to take a walk in the gardens and trails on the campus. In Session 21, a guest lecturer was invited to enable the participants to learn about and observe insects, birds, and animals in the garden. In Session 22, they created a rock garden and planted plants that can grow in rock gardens. In Session 23, using cockscomb they planted in Session 6, they learned from an expert how to make cockscomb flower tea, and tasted it. In Session 24, they studied garden plants while walking through the campus, and in Session 25, they created their own Christmas garden in a container. In Session 27, they studied the plants in the garden and made a garden plant book. In Sessions 28 and 29, they prepared for the wintering of garden plants and cleared the garden; participants dug up bulbs, installed wind breaks for shrubs and perennial plants, and covered trees with jute tapes to protect them. In Session 30, a garden party was held to review the activities with the participants and finalize the program (Table 2).

To verify the psychological effects of the gardening program, a parenting stress test, Korean-style mental health assessment (MHA), and satisfaction survey on the program were conducted. The Korean version of the Parenting Stress Index (K-PSI-4) is a reliable and valid measurement tool, which was developed and standardized by translating the latest version of the US Parenting Stress Index (4th edition) (PSI-4, Abidin, 2012), into Korean (Jung et al., 2019; Child and Parent Domains, and total stress score: Cronbach’s α = 0.90–0.97; sub-scales: Cronbach’s α = 0.78–0.87). The K-PSI-4 consists of 101 items to measure parenting stress (PS) in the relationship between parents and children and 19 items to measure life stress (LS). In this study, the results of two domains of PS (Child and Parent domains) were analyzed, excluding the LS domain that is not included in the total PS values. Each item is evaluated by dividing into 6 subscales of Child domain (Distractibility, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, Demandingness, Mood, Acceptability) and 7 subscales of Parent domain (Competence, Isolation, Attachment, Health, Role restriction, Depression, Relationship with spouse). Each subscale in the Child domain is not the children’s actual characteristics, but the characteristics of children as perceived by the parents. It can be said that the four variables of Distractibility, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, and Demandingness are subscales related to children’s disposition, while Acceptability and Mood are subscales that are influenced by parental personality and perception of the self (Jung et al., 2019). First, the subscale Distractibility indicates the degree of hyperactivity, distraction and short attention span, non-conformity, and difficulty in concentrating on tasks; Adaptability represents children’s ability to adapt to changes in the physical and social environment; Reinforces parent indicates the extent to which parents experience positive responses from their children; Demandingness refers to the degree to which children place demands, including through crying, physical clinging, and frequent requests for help; Mood indicates the degree to which children’s emotions such as depression and excessive crying are expressed as dysfunctional behaviors; Acceptability represents the degree to which a child’s physical, mental, and emotional characteristics match the parents’ hopes for their child. In the Parent domain, the subscale of Competence refers to the sense of competence felt toward parenting as a caregiver; Isolation refers to the degree of lack of social support available to fulfill a parenting role; Attachment represents the emotional closeness and bond that parents feel towards their children; Health indicates the current level of the physical health of parents required for parenting behavior; Role restriction refers to the perception of the limitations of freedom and personal identity as a result of parental roles; Depression indicates parents’ depressed emotional state; Relationship with spouse refers to the degree of emotional and behavioral support one receives from one’s spouse to fulfill a parental role. Of the total of 101 items, questions for 91 items were constructed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 point for “Strongly disagree” to 5 points for “Strongly agree”. For the remaining 10 items, 4 to 5 examples were presented for selection. The sub-domain score was calculated as the total points of the items, and a higher score means higher parenting stress.

A Korean-style MHA was conducted using the online platform MINDEEP, provided by Korea University; five types of test tools were used to measure quality of life, mindfulness, depression, anxiety, and daily vitality. The Korean version of the WHO Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF, Cronbach’s α = 0.90) is a tool developed according to the guidelines of the World Health Organization. It is a 26-item instrument consisting of 4 domains related to quality of life: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental health. The score for each domain is calculated by multiplying the average of the items by 4; the total quality of life score is the sum of all domain scores, ranging from 20 to 100 points; a higher score means a higher quality of life. The Korean Version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (K-MAAS, Cronbach’s α = 0.87) is a scale for evaluating open and receptive awareness and attention, consisting of 15 items on a 6-point Likert scale. It is measured ranging from 15 to 90 points, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The Korean Screening Assessment for Depressive Disorders (K-DEP, Cronbach’s α = 0.94) is a self-reporting test for screening major depressive disorder, consisting of a total of 12 items on a 5-point Likert scale. The Korean Screening Tool for Anxiety disorders (K-ANX, Cronbach’s α = 0.97) is a tool for screening generalized anxiety disorder, consisting of 11 items on a 5-point Likert scale. For K-DEP and K-ANX, to which the item response theory (IRT) is applied to by statisticians, the weight of the selected items is calculated, and the score is calculated by reflecting this weight. For the depression and anxiety scales, higher scores indicate higher levels of depression and anxiety. The Daily Vitality Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) consists of 5 items on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 5 to 25 points, with higher scores indicating higher daily vitality.

To evaluate the effect of the program conducted in this study, parenting stress was tested before and after the program using K-PSI-4. A Korean mental health assessment was conducted with the five types of test tools via an online platform before and after the program. A satisfaction survey on the program was conducted after the program using a self-reporting questionnaire consisting of 7 items of satisfaction with overall operation and effect of the program (using mixed response formats including 7-point Likert scale, multiple choice, and narrative response).

Data Analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 18. To verify the effect of gardening activities, the pre-and post-test results were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Regarding the satisfaction survey on the program, descriptive analysis and frequency analysis were performed for each item.

Participants in the program were 12 parents or primary caregivers nurturing children with developmental disabilities: 2 fathers, 9 mothers, 1 grandmother. The average age of the subjects was 45 years old, with 1 person in their 30s (8%), 9 in their 40s (75%), 1 in their 50s (8%), and 1 in their 60s (8%). For educational background, 83% of the participants were college graduates, and 17% high school graduates.

In the pre-test of parenting stress, the total parenting stress score was at the normal level (186–253 points) for 8 persons and at the high level (300 points or more) for 2 persons. For all subjects, the stress index in the Child domain was found to be higher than in the Parent domain.

After the gardening program, the total level of parenting stress decreased by a statistically significant (p < .05), from 261.6 points in the pre-test to 241.5 points in the post-test. The total stress level in the Child domain also showed a significant decrease, from 120.1 to 109.1 points (p < .05). The total stress level in the Parent domain decreased from 141.5 to 132.4 points, but this was not statistically significant.

For the Child domain, parenting stress decreased in all subscales (Distractibility, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, Demandingness, Mood, Acceptability). Distractibility decreased from 26.9 points in the post-test to 23.3 points in the post-test, and Adaptability from 29.0 to 28.5 points, which was not statistically significant. Reinforces parent also decreased from 9.9 to 9.3 points, which was not significant. Demandingness decreased from 23.4 to 20.9 points, and Mood from 11.4 to 10.0 points, which again was not statistically significant. Of the subscales of the Child domain, only Acceptability showed a statistically significant decrease, from 19.6 points to 17.2 points (p < .05), indicating that the degree to which parents’ physical, mental, and emotional expectations of their children is met has increased. In addition, as the four variables of Distractibility, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, and Demandingness are subscales related to the child’s disposition, and Acceptability and Mood are subscales affected by parental personality and perception of the self (Jung et al., 2019), this suggests that parents’ gardening activities caused changes in their psychological environment, and reduced total parenting stress in the Child domain through a significant change in the subscale of Acceptability.

In the Parent domain, parenting stress was reduced in 4 out of 7 subscales (Isolation, Health, Role restriction, and Depression). In particular, Isolation showed a significant decrease, from 16.2 to 12.6 points (p < .05), indicating that the social support formed through exchange and communication had a significant change during gardening activities. It can be said that the subjects, who are parents with common difficulties in nurturing CDDs, developed mutual emotional and social support through continuous exchange and communication in the process of performing gardening activities together. The subscale of Health decreased from 12.1 to 10.9 points, and of Role restriction from 21.5 to 20.2 points, which was not statistically significant. Depression decreased from 23.4 to 18.9 points, which was not statistically significant. The remaining three subscales (Competence, Attachment, Relationship with spouse) were maintained, or slightly increased, but the increase was not statistically significant (Table 3).

As such, the results of the test of parenting stress indicate that gardening activities reduce parenting stress, have a positive effect on the relationship with children through improvement of the subscale of Acceptability of the Child domain, and reduce the burden of parenting by forming social support, including relieving the feeling of isolation. This seems to be similar to the results of the earlier study on the burden of caregivers: horticultural therapy programs for caregivers with common difficulties in caring for the elderly with dementia reduced the depressive levels of caregivers overall and relieved their burden of care (Kim et al., 2020).

A Korean-style MHA was conducted to measure the five scales of depression, anxiety, daily vitality, quality of life, mindfulness. After the gardening program, depression was decreased by a significant level, from 3.34 points in the pre-test to 1.24 points in the post-test (p < .05); daily vitality was increased by a significant level from 18.25 to 21.38 points (p < .05). Anxiety was decreased from 3.64 to 0.68 points; quality of life was also increased from 91.20 to 100.88 points; and mindfulness was increased from 73.63 to 76.13 points, which was not statistically significant (Table 4).

Based on the MHA, gardening activities were found to have the effect of improving the subject’s depression and increasing daily vitality. Psychological and emotional effects have been also found in other studies based on gardening activities. A 10-session community gardening program improved stress, including decreased levels of the hormone cortisol (Jang et al., 2019). Psychologically positive effects including self-esteem were reported through a 16-session gardening activity-oriented horticultural therapy program for the homeless (Kim et al., 2020). For the bereaved, the garden healing program conducted twice a week for 10 sessions was effective in psychological improvement including depression, anxiety, and lethargy (Na, 2020). A review of 11 studies regarding the psychological and physiological effects of gardens reported that the garden environment had the effect of relieving physiological stress and improving negative psychological states (Kang et al., 2020). This study involved a 30-session garden program over 15 weeks, and thus involved more sessions or a longer program period compared to existing studies on gardening activities. However, this study has a limitation in that it was not possible to analyze the psycho-emotional effects depending on the period of gardening activities because quarterly measurement results were not collected for each scale.

Satisfaction with the program (very satisfied: 7 points) was 6.9 points on average, indicating a very high level of satisfaction. In particular, to the question of whether the program was effective, all participants answered, “Strongly Agree” (7 points), and the willingness to continue participation was also very high, with an average of 6.8 points.

Based on multiple responses regarding the program’s effects, “relieving daily stress” (37.5%) was the most common response, followed by “acquiring knowledge about plants and gardens” (20.8%) and “maintaining physical health” (16.6%). In addition, responses of improving relationships with children, overcoming current difficult state of mind, and motivating self-development were given by 8.3% of participants. However, none of the respondents answered that the relationship with other family members was improved (Fig. 1).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of gardening activities on parenting stress and mental health of parents nurturing CDDs. A 30-session gardening program was conducted for 11 parents and 1 grandmother raising CDDs in elementary school. The effect of the gardening program was examined based on gardening activities, which were composed of gardening (77%), events (16%), and theory (7%).

After the program, it was found that the total level of parenting stress and the total stress level in the Child domain was decreased by a statistically significant level. In the Children’s domain, the subscale Acceptability decreased by a significant level, indicating that the degree to which parents’ physical, mental, and emotional expectations of their children is met was increased. It was shown that parents’ gardening activities caused changes in their psychological environment, and reduced the total level of parenting stress in the Child domain through a significant change in the subscale of Acceptability. In the Parent domain, only the subscale of Isolation showed a statistically significant decrease. This indicates that in the process of a variety of gardening activities including planting and caring for plants together, the 12 parents generated mutual emotional and social support through exchanges and communication about the common difficulties of nurturing CDDs. The subscale of Depression was greatly reduced in the Parental domain, and depression in the Korean-style MHA was also decreased by a significant level. In addition, Daily vitality was increased by a significant level. This suggests that gardening activities are effective as a means to reduce the emotional difficulties caused by nurturing CDDs and increase daily vitality and quality of life. After the program, a satisfaction survey of the participants was conducted. Their satisfaction with the gardening program (very satisfied: 7 points ) was found to be very high, with an average score of 6.9 points. In particular, when asked whether the program was effective, all participants answered, “Strongly agree” (7 points). For questions about the specific effectiveness of the program, the response of “relieving daily stress” (37.5%) was the highest, followed by “acquiring knowledge about plants and gardens” (20.8%) and “maintaining physical health” (16.6%). The willingness to continue participating in such programs was also found to be very high, with an average score of 6.8 points.

As a result of this study, gardening activities were found to be effective psychologically and emotionally, including reducing parenting stress and improving depression and anxiety of parents nurturing CDD. Twelve subjects with common difficulties in raising CDDs participated in garden activities together to form social support and reduce feelings of isolation, and increased their daily vitality and quality of life through gardening. In addition, it can be seen that gardening activities are effective as a means of emotional and psychological support not only for persons with disabilities or diseases, but also for caregivers and guardians who have the same difficulties. In the future, it is necessary to study various programs of gardening activities, and to further determine the effects of gardening activities through research on participants with various characteristics. The limitations of this study were the small number of participants, which made it difficult to generalize the effects of the program, and the fact that period of the program included the summer monsoon and seasonal typhoons, making it difficult to proceed with the activities at times. In future research, it will be important to increase the number of participants and secure the reliability of the results by comparing the experimental and control groups. In addition, by examining the characteristics of the Korean climate, research should be planned so that such programs can proceed smoothly without interruption. In verifying the effect of such activities, it is considered desirable to examine the correlation between the physiological and psychological effects by simultaneously studying physiological and psychological changes, because gardening activities are focused on outdoor activities in the garden.

Table 2

Gardening program

Table 3

Changes in parenting stress before and after the implementation of the gardening program

| Parenting stress | Before | After | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child domain | Distractibility | 26.9 ± 3.6 | 23.3 ± 6.9 | −1.542 | 0.123 |

| Adaptability | 29.0 ± 5.6 | 28.5 ± 3.9 | −0.687 | 0.492 | |

| Reinforces parent | 9.9 ± 3.4 | 9.3 ± 1.8 | −0.962 | 0.336 | |

| Demandingness | 23.4 ± 5.8 | 20.9 ± 5.4 | −1.546 | 0.122 | |

| Mood | 11.4 ± 5.3 | 10.0 ± 4.3 | −1.436 | 0.151 | |

| Acceptability | 19.6 ± 3.2 | 17.2 ± 2.9 | −2.214 | 0.027* | |

|

|

|||||

| Total stress in child domain | 120.1 ± 19.1 | 109.1 ± 17.6 | −2.100 | 0.036* | |

|

|

|||||

| Parent domain | Competence | 36.9 ± 7.6 | 37.0 ± 5.2 | −0.282 | 0.778 |

| Isolation | 16.2 ± 6.3 | 12.6 ± 4.4 | −2.023 | 0.043* | |

| Attachment | 13.2 ± 4.2 | 14.4 ± 3.5 | −1.078 | 0.281 | |

| Health | 12.1 ± 3.7 | 10.9 ± 4.8 | −0.845 | 0.398 | |

| Role restriction | 21.5 ± 5.9 | 20.2 ± 5.6 | −0.679 | 0.497 | |

| Depression | 23.4 ± 5.2 | 18.9 ± 7.7 | −1.820 | 0.069 | |

| Relationship with spouse | 18.1 ±5.4 | 18.4 ± 5.9 | −0.105 | 0.917 | |

|

|

|||||

| Total stress in parent domain | 141.5 ± 31.4 | 132.4 ± 25.3 | −1.367 | 0.172 | |

|

|

|||||

| Total parenting stress | 261.6 ± 49.0 | 241.5 ± 36.9 | −2.521 | 0.012* | |

Table 4

Effects of gardening program on mental health

| Variable | Before | After | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mind Health | Depression | 3.34 ± 2.89 | 1.24 ± 1.82 | −2.201 | 0.031* |

| Anxiety | 3.64 ± 3.17 | 0.68 ± 1.50 | −1.572 | 0.156 | |

| Daily Vitality | 18.25 ± 3.66 | 21.38 ± 3.82 | −2.201 | 0.031* | |

| Quality of Life | 91.20 ± 18.20 | 100.88 ± 19.54 | −1.893 | 0.063 | |

| Mindfulness | 73.63 ± 8.98 | 76.13 ± 10.40 | −0.771 | 0.484 |

References

Cho, I.S., K.I. Moon. 2016. Factors affecting the lfe quality in mothers of children with disabilities. Journal of The Korean Society of Maternal and Child Health. 20(2):119-131.

https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2016.20.2.119

Jang, H.S., G.M. Gim, S.J. Jeong, J.S. Kim. 2019. Community gardening activities and their effects on mental health of residents. People, Plants, and Environment. 22(4):333-340.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2019.22.4.333

Jeon, H.I. 2007. A qualitative study on the experiences and support needs of mothers of cildren with mental retardation. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 23(1):265-285.

Jung, J.E., G.H. Jo, J.H. Yang, E.H. Park. 2020. An analysis of research trends related to family support of people with physical disabilities: Research from 2010–2019. Korean Journal of Special Education. 55(2):163-185.

https://doi.org/10.15861/kjse.2020.55.2.163

Jung, K.M., S.I. Lee, C.S. Lee. 2019. Standardization study for the korean version of parenting stress index fourth edition(K-PSI-4). Korean Journal of Psychology: General. 38(2):247-273.

Kang, K.S. 2016. Study on the difficulty of parents of children with developmental disabilities, recognition of the quality of life and needs for the services to improve the quality of family support services. The Journal of Inclusive Education. 11(2):217-247.

https://doi.org/10.26592/ksie.2016.11.2.217

Kang, K.S., Y.J. Kim. 2012. Negative reinforcement trap perceived through a mother’s experiences on bringing up her child with intellectual disabilities. The Journal of Anthropology of Education. 15(2):85-122.

https://doi.org/10.17318/jae.2012.15.2.004

Kang, M.J., S.J. Kim, H.Y. Jin, S.J. Song, J.Y. Lee. 2020. A systematic review of current research on the health benefits of garden environment. Journal of the Korea Institute of Garden Design. 6(3):282-292.

https://doi.org/10.22849/jkigd.2020.6.3.008

Kim, S.J. 2021. A Pilot Study on the Psychological and Physiological Effects of Garden Environment. Master’s thesis. Hankyung University, Gyeonggi-do, Korea..

Kim, S.K. 2010. Maternal parenting stress, social support and parenting behaviors with preschool children with disabilities: The mediating efect of parenting efficacy. Doctoral dissertation. Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea..

Kim, Y.H., C.S. Park, H.O. Bae, E.J. Lim, K.H. Kang, E.S. Lee, S.H. Jo, M.R. Huh. 2020. Horticultural therapy programs enhancing quality of life and reducing depression and burden for caregivers of elderly with dementia. Journal of People, Plants, and Environment. 23(3):305-320.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2020.23.3.305

Kim, Y.H., S.H. Lee, C.S. Park, H.O. Bae, Y.J. Kim, M.R. Huh. 2020. Gardening activity-oriented horticultural therapy program to Care psychological, emotional and social health for the elderly in long-term homeless living facilities: A pilot study. Journal of People, Plants, and Environment. 23(5):565-576.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2020.23.5.565

Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute. 2013 Factfinding survey of disabled children and families Retrieved from https://www.koddi.or.kr/data/research01_view.jsp?brdNum=7400850&brdTp=&searchParamUrl=brdRshYnData%3Ddata%26amp%3BsearchType%3D%26amp%3BpageSize%3D20%26amp%3BbrdType%3DRSH%26amp%3BbrdTp%3D%26amp%3Bpage%3D12%26amp%3BsearchKeyword%3D%26amp%

.

Korea Institute for Health and Social Affair. 2015 A study on the integrated operation plan of child-rearing support for children with disabilities and activity support for the disabled Retrieved from https://www.kihasa.re.kr/publish/report/view?searchText=%EC%9E%A5%EC%95%A0%EC%95%84%EB%8F%99&page=1&type=all&seq=28826

.

Ministry of Health & Welfare. 2020 Number and status of the disabled registered Retrieved from http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp

.

Ministry of Health & Welfare. 2022 Disabled Services Policy Retrieved from http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp

.

Na, S.Y. 2020. Effects of garden healing programs on anxiety, depression, blood pressure and cortisol of bereavement. Doctoral dissertation. Gyeongsang National University, Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea.

Park, S.A., M.S. Jeong, M.W. Lee. 2015. An analysis of the healing effects of forest therapy and horticultural therapy. Journal of the Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture. 43(3):43-51.

Yun, D.L., M.J. Yun. 2019. Survey of educational programs related to gardening in korea. Flower Research Journal. 27(3):186-194.