|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 25(2); 2022 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: Recent research on cultural heritage has highlighted resident participation as an ideal method of managing local cultural heritages. However, many studies have raised questions about the practicality of this approach. This research undertook case studies of Jeoji-ri and Handong-ri on Jeju Island, South Korea focusing on how resident participation increases based on the related stakeholders, local heritages (natural, tangible and intangible cultural heritages) and social capital (trust and networking).

Methods: Sixty-one completed questionnaires were collected from adult residents of both villages (28 from Jeoji-ri and 33 from Handong-ri), and the resulting quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and the R programming language. In addition, two semi-structured interviews were undertaken with the leaders of each village, and the resulting qualitative data were analysed thematically.

Results: The study found that the village leaders of Handong-ri and Jeoji-ri successfully encouraged trust and participation among village residents, suggesting that resident participation is largely influenced by the relevant stakeholders and the social capital of residents. Networking and intangible cultural heritages, such as rituals or village oral traditions, positively influence resident participation.

Conclusion: This study suggests that the active utilisation of intangible cultural heritages and the networks developed by cooperating with essential stakeholders are vital for encouraging resident participation.

Methods: Sixty-one completed questionnaires were collected from adult residents of both villages (28 from Jeoji-ri and 33 from Handong-ri), and the resulting quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and the R programming language. In addition, two semi-structured interviews were undertaken with the leaders of each village, and the resulting qualitative data were analysed thematically.

Results: The study found that the village leaders of Handong-ri and Jeoji-ri successfully encouraged trust and participation among village residents, suggesting that resident participation is largely influenced by the relevant stakeholders and the social capital of residents. Networking and intangible cultural heritages, such as rituals or village oral traditions, positively influence resident participation.

Conclusion: This study suggests that the active utilisation of intangible cultural heritages and the networks developed by cooperating with essential stakeholders are vital for encouraging resident participation.

Public participation is generally accepted worldwide as a key element of heritage management; however, it is difficult to implement at a practical level (Thomas and Lea, 2014; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; UNESCO, 2019a, b). The ‘public’ in public participation comprises a range of stakeholders, including residents, government officials, tourists, collectors, and foundations, depending on the local context (Thomas and Lea, 2014). Reddel and Woolcock (2004) and Perkin (2010) highlighted that in promoting resident participation, such important stakeholders should be taken into account. In addition, previous studies have revealed that residents’ participation in the management of cultural resources is closely related to other initiatives, such as the sustainable development of the region, responses to climate change, cultural heritage preservation activities, and world heritage site protection (ICOMOS, 2008; Vollero et al., 2018; May, 2020). Thus, this study focuses on the emerging importance of residents rather than that of other stakeholders, such as tourists or experts (Jimura, 2011; Vollero et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Zhang and Brown, 2022).

Despite the importance of resident participation, many scholars have raised questions about its applicability to real-life settings (Reddel and Woolcock, 2004; Landorf, 2009; Perkin, 2010; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020). For example, Perkin (2010) indicated that resident participation could be challenging when local communities are not well-established or when conflicts exist between residents. Li et al. (2020) also implied that the Chinese government’s policies for managing cultural heritages are profit-based, and lack resident participation. Kang and Lee (2015) conducted an empirical analysis of the residents of Jeju Island and demonstrated that they were dependent on central or local government-run subsidiary projects, thus increasing the difficulty of encouraging voluntary resident participation.

Considerable research has suggested establishing better connections and sustaining interactions between residents to facilitate resident participation (Landorf, 2009; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020). Perkin (2010), for example, focused on project managers as mediators who address potential conflicts and incorporate the needs and motivations of residents in ways that can successfully increase their participation. For this reason, village leaders in this study play a role similar to that of a project manager in terms of ensuring resident participation in community groups. Thus, Rasoolimanesh et al. (2017) and May (2020) concluded that resident participation could be achieved by forming trust and strengthening the networks among residents, analysing important local stakeholders, and utilising intangible cultural resources.

However, these studies have limitations in that they have not comprehensively analysed the relationships between local stakeholders, the level of trust and the strength of the networks between residents, or local cultural resources. Many previous studies have also called for practical case studies considering specific regions and circumstances to explore the relationships between resident participation, trust, and networking among residents and rural heritage (Perkin, 2010; Li et al., 2020).

In this context, this study focuses on Jeoji-ri and Handong-ri on Jeju Island, South Korea as case studies of locations in which resident participation has been successfully promoted. Jeju Island is a special autonomous region with well-formed village communities (Ki et al., 2020). Of the various villages on Jeju Island, Song et al. (2020) chose Jeoji-ri and Handong-ri as representative villages based on the number of farm households, economic diversification, and accessibility. Based on these analytical results, this study also chose Jeoji-ri and Handong-ri as the cases to be analysed.

By examining the case of Jeju Island, this study aims to investigate how resident participation is increased by various important stakeholders, social capital (focusing primarily on trust and networking among residents) and cultural heritage interactions to overcome the hurdle of lack of resident participation. Based on the findings, this study reveals that networking among important stakeholders and intangible heritages in communities are key to encouraging resident participation. This study presents a review of the literature, explains the methodology, examines the results, discusses the implications of the findings and derives a conclusion.

Public participation is both a well-known concept and a contested term in the heritage sector (Thomas and Lea, 2014; Li et al., 2020) because the public aspect of public participation can be interpreted in numerous ways. Generally, it involves various stakeholders, such as residents, government officials, tourists, collectors and foundations, depending on the local context (Thomas and Lea, 2014). Despite the breadth of possible interpretations, Li et al. (2020) argued that international definitions, such as those put forth by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) in their respective published papers, regard residents as the primary form of the public, whereas government officials, experts and other social actors assume a supplementary role as facilitators. Thus, this study also examined previous research that focused on residents within the concept of the public.

Resident participation has been an essential aspect of heritage management not only in the UK but also worldwide (Millar, 2005; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; UNESCO, 2019a, 2019b; Li et al., 2020) because of the growing interest in the idea of local and regional communities taking responsibility for their cultural heritages (Mydland and Grahn, 2012; Jaafar et al., 2005, Rasoolimanesh, 2015), which corresponds well with overall trends toward decentralisation and self-governance (Historic England, 2020; Fan, 2014). Accordingly, numerous international guidelines and published articles highlight the indispensability of community participation for various reasons, such as sustainable development, climate change response, heritage preservation and world heritage site protection (ICOMOS, 2008; Jimura, 2011; Vollero et al., 2018; May, 2020).

For example, ‘Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape’ and ‘Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention’ by UNESCO (2019a, 2019b) both recognise resident participation as essential in heritage management practices in terms of ensuring that the needs of the local communities are considered in the process (Schmidt, 2014). The international heritage organisation ICCROM also published a guidance document discussing people-centred approaches to heritage management in 2015 (Li et al., 2020).

Government and nongovernmental organisations, such as Historic England (2020) and the National Trust (2020), also emphasise community participation to preserve cultural heritage sites. Every year, Historic England (2020) publishes the ‘Heritage at Risk’ report, encouraging the active involvement of residents in managing their precious local heritage. Likewise, the National Trust (2020) exemplifies a new direction for managing cultural heritage sites by emphasising three key concepts: community engagement, education, and sustainability—all mediated through the active participation of local communities.

A number of world heritage case studies demonstrate the fundamental nature of community participation, but the motivations behind community participation can differ greatly according to the local context (Landorf, 2009; Chirikure et al., 2010). Using the example of the Lake District, UK, May (2020) suggested that community participation is highly valued in the UK and often encouraged by appeals based on the endangered status of heritage sites; further, May argued that raising awareness of these sites’ precariousness to facilitate community participation is an essential tactic used across Europe. Likewise, Vollero et al. (2018) confirmed that this eco-centric attitude plays a significant role in encouraging public participation among the residents of the Amalfi Coast, Italy. Thus, adopting an eco-friendly strategy can, in some countries, help encourage residents to participate in their local communities.

However, focusing on the endangered status of heritage sites does not work well as a strategy across all countries and regions. Jimura (2011), using the case study of Shirakawamura, a historic world heritage village in Japan, suggested that conserving cultural heritage sites is not always a priority for the Japanese people. Rather, they are more concerned with the economic benefits of world heritage sites and the possibilities for tourism. Similarly, a case study of Lumbini, Nepal—the birthplace of Buddha—suggests that community participation should be linked to economic benefits to encourage people to support cultural heritage sites and acknowledge their value (Coningham and Lewer, 2019).

Many case studies have also explicitly demonstrated that intangible heritages, such as traditions, rituals and other local practices, are inextricably linked to resident participation (Poulios, 2014; Brown, 2017; Vollero et al., 2018; Zhong and Leung, 2019; May, 2020). For example, May (2020) revealed that resident participation in the UK’s Lake District is facilitated by local shepherding practices, which are an important element of the area’s intangible heritage. This may offer possibilities for resident participation through intangible heritages in other local contexts; however, the characteristics of intangible heritage differ greatly between locations due to the great diversity of local contexts (Meissner, 2021; Ranwa, 2021). Based on these studies, this study chose to explore how an intangible heritage can help motivate residents to participate, as it fosters a sense of community spirit among residents.

Despite the importance of heritage-led motivations for resident participation, many studies have revealed that a strong sense of community, expressed in the form of mutual trust and cooperation, as well as networking and partnerships, plays an important role in facilitating resident participation in well-developed communities (Yang and Kang, 2008; Brown, 2017; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Vollero et al., 2018). One example of this can be found in Durham, a city in the UK. Puddifoot (2003) demonstrated that Durham has a strong community spirit featuring substantial local cooperation. Evidence for the strength of this community can be observed in the management plan for Durham Cathedral, which demonstrates a broad range of networking and partnerships that encompass various local community stakeholders, including a representative appointed by UNESCO (Brown, 2017). Notably, this management plan considers the intangible heritages of Durham Cathedral, such as pilgrimages, community outreach and social traditions associated with Durham University (Brown, 2017), exemplifying a high level of resident participation. These studies suggest that residents participate in managing heritage sites by forming networks within their local communities, implying that these networks positively affect resident participation in community activities (Puddifoot, 2003; Brown, 2017; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017).

A case study of George Town in Malaysia also suggested that establishing connections and sustaining interactions between community members is essential for facilitating the residents’ active participation (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017). This study also highlighted that appropriate communication channels, such as public media, play an important role in encouraging spontaneous community participation, generating reciprocal trust among residents and improving their sense of belonging to their local community (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2015, 2017). Thus, this research revealed that residents interact with each other more efficiently and actively participate in community activities more actively by forming a network facilitated by mass media.

Although the efforts by residents to protect their landscapes and promote their local economies have been recognised as primary motivators for community participation (Jimura, 2011; Vollero et al., 2018; Coningham and Lewer, 2019; May, 2020), social capital, including social networks and trust among residents, provides a pathway for facilitating active community participation (Landorf, 2009; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2015, 2017; Brown, 2017). In cases where a community is disengaged, strong leadership is emphasised as a crucial element in mediating and addressing potential conflicts that may stand in the way of voluntary resident participation (Perkin, 2010).

Moreover, Perkin (2010) addressed these issues from a different perspective, noting that understanding the characteristics and differences of local communities should be prioritised to identify potential supporters and develop partnerships with related heritage groups. To further ensure the success of projects driven by resident participation, Perkin (2010) also emphasised the role of project managers, who must understand the motivations and needs of all of the involved local groups and address any problems as necessary. Additionally, Jaafar et al. (2015) pointed out the role of young residents as drivers of culture, arguing that local cultural heritage sites can be successfully promoted and managed by inducing active participation among young residents in particular. Thus, this study included the village leaders who can serve as project managers, as well as young residents as drivers of culture. Village leaders are people who personally or collectively influence residents to follow a common goal or direction (Choi and Kim, 1994)

However, these findings have little applicability to situations in which the local community is disengaged from nearby cultural heritage sites (Landorf, 2009; Perkin, 2010) or where resident participation opportunities are generally lacking because the central and/or local governments does not acknowledge the vital role of communities in maintaining cultural heritage sites (Mydland and Grahn, 2012; Li et al., 2020). To address these issues, Landorf (2011) suggested that current heritage management processes should shift from centralised and exclusionary approaches to more participatory and holistic ones. More specifically, Li et al. (2020) proposed that networking strategies, such as forming committees and hosting meetings and workshops, should be encouraged to increase the responsibility of local communities and train residents as local professionals. This strategy tackles the three main challenges of cultural heritage management in China: insufficient community participation, profit-driven decision-making, and centralised governance. Nevertheless, local governments manage numerous existing cultural heritage sites; thus, this study considered government officials to be key stakeholders.

The existing literature explicitly demonstrates that resident participation varies distinctively depending on the local contexts (Landorf, 2009; Chirikure et al., 2010). Accordingly, mechanisms that enable residents to participate in the management of their cultural heritages must be explored within their specific local contexts. Thus, Reddel and Woolcock (2004) and the UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020) both concluded that various locally relevant stakeholder analyses should be undertaken to explore community engagement in various contexts. With this in mind, this study reviews existing studies related to Jeju Island to identify such locally relevant stakeholders in that geographical context.

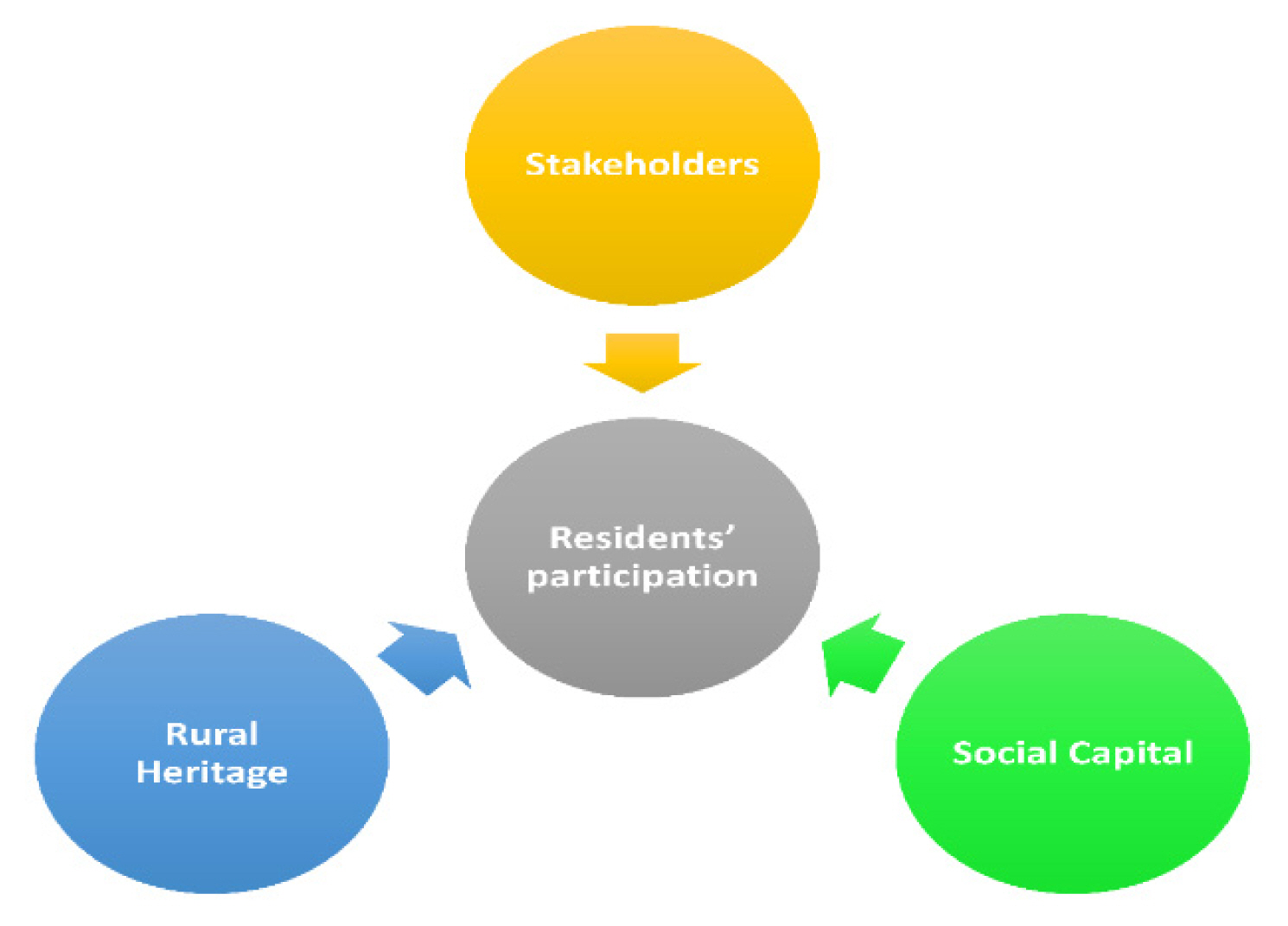

The existing literature in this field has limitations, in that the researchers have not comprehensively analysed how rural heritage influences resident participation in community activities (Li et al., 2020). Thus, the present case study is both pertinent and worthwhile for exploring a well-developed community area and providing an additional analysis of the important stakeholders and social capital in the form of trust and networks among residents, all of which are key features emphasised by Reddel and Woolcock (2004) and Perkin (2010), as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Considering the above research framework (Fig. 1), this research undertakes a case study of two villages located on Jeju Island to explore how resident participation is influenced by social capital (networking and trust among residents), stakeholders (government officials, village leaders, young residents and newly relocated residents) and types of rural heritage (natural, tangible and intangible).

Jeju Island is one of the South Korean provinces situated between South Korea and Japan. Due to its strategic position, Jeju Island has served as a maritime transportation hub, and has a complicated history involving foreign invasions and political upheavals (Kim, 2008; Ko, 2019). Throughout its history, the most effective defence for residents has been to develop a strong community and support one another in overcoming difficulties. Even today, Jeju Island has well-established communities based on local villages and prides itself on its strong, community-based autonomy. A representative example of this is the Jeju Haenyeo (woman divers who dive to collect seaweed, shellfish, and other sea-food whilst holding their breath), registered as UNESCO World Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2016. They have formed a Haenyeo community of mutual respect, enabling them to successfully maintain their shared identity and support eacth other (No, 2021).

Although a strong community could denote close-knit networks and mutual trust among residents, it also can imply the rejection of outsiders; Chilvers and Kearnes (2016), for instance, noted that close-knit communities are often formed by exclusion. Coningham and Lewer (2019) also suggested that power structures, business interests, public resource access, political influence, marginalisation, and religious differences all can exist within village communities, creating a range of conflicts and tensions. These viewpoints of Chilvers and Kearnes (2016) and Coningham and Lewer (2019) imply that Jeju Island may be susceptible to such conflicts between long-term residents and newly relocated residents, which means that collective leadership may be required to mediate in a situation of internal discord. Thus, this study differentiated newly relocated residents from existing residents as stakeholders, defining them as those who voluntarily migrated to rural areas based on Article 29 Subparagraph 2 of the Framework Act on Agriculture, Rural Community and Food Industry (Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, 2020).

What defines residential ‘communities’ can be interpreted in multiple different ways, as they can appear in various forms (Waterton and Smith, 2010). The present study uses the statutory definition of community as legislated by Jeju Special Self-governing Province to address the multifaceted concept of community. According to Jeju’s Special Self-governing Province Ordinance for the Establishment of Local Communities for Settlements, the term ‘community’ represents a communal village where residents live together while sharing a sense of belonging to a specific area, such as a ‘ri’ (Jeju Special Self-governing Province, 2017). A ‘ri’ is South Korea’s smallest administrative unit composing a region, and primarily exists in rural areas.

Unlike other regions of Korea, Jeju Island has a ‘ri’ community centre operated by resident volunteers (Ki et al., 2020), which helps local residents form community consciousness and a shared identity (Jang and Lee, 2001), indicating that the village community is well-established. In July 2006, the Jeju Special Self-governing Province was established as a leading model for decentralisation and local autonomy, providing the legal basis for community activities through Article 45 of the Special Act on the Establishment of Jeju Special Self-governing Province and the Development of Free International City (Ministry of the Interior and Safety, 2021).

Two villages, Handong-ri and Jeoji-ri, were chosen from within the ri administrative areas to examine this topic more closely (Fig. 2). These two villages are representative villages among the ri-based villages found on Jeju Island (Ki et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020). This study randomly surveyed 61 residents (28 from Jeoji-ri and 33 from Handong-ri) and interviewed each village leader to explore the relationship between residents’ perceptions of their participation and their awareness of cultural heritage, the role of other stakeholders and the level of social capital.

Most studies related to residents’ perceptions use survey techniques (Pearce, Moscardo, and Ross, 1996), but survey techniques have limitations in that it is difficult for respondents to add their own opinions beyond the provided answer choices. Thus, Jimura (2011) argued that qualitative methods, such as interviews, must be conducted to supplement survey techniques. This study adopted a literature review of studies conducted on villages, village observations made through village visits, semi-structured interviews conducted with each village leader and surveys of residents to overcome these difficulties (Song and Han, 2012) and better understand the multidimensional relationships between stakeholders, social capital and heritage, with a focus on resident participation (Fig. 3).

The author surveyed 61 randomly chosen residents, asking questions such as ‘To what extent do you consider your village to have village leaders, young people or government officials?’ ‘To what extent do you consider your village to have trust, participation, and networking between neighbourhoods?’ and ‘To what extent do you consider your village to have natural, tangible or intangible heritages?’ Sixty-one completed questionnaires were collected (Table 1), and the quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18 and the R programming language. Two semi-structured interviews, providing qualitative data, were analysed thematically.

Previous studies have underscored the need to explore the roles of various important stakeholders in communities and their relationships with resident participation (Reddel and Woolcock, 2004; Perkin, 2010). This study analyses the correlations between stakeholders, social capital and heritage and the participation variable regarding each village to discern links between stakeholders, social capital and heritage (particularly regarding participation). Exploring causal relationships using analytical results of correlation analysis is difficult (Hill, 2015); thus, a multiple regression analysis was also conducted to better understand the manner in which stakeholders, social capital, and heritage influence resident participation. For the purpose of this research, stakeholders, social capital, and heritage are defined based on the previous research and detailed information about the individual variables, as described in Table 2.

In addition, this study conducted principal factor and reliability analyses to verify the internal consistency between the variables. As a result, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Test (KMO) showed that each category is greater than 0.5, and Bartlett’s sphericity test showed a significance probability of all variables (p < .001), indicating that the factor analysis model was suitable. In addition, since the variance ratio of each category is more than 60 percent and the factor loading value of every variable is more than 0.4, the accountability of each category is robust, justifying the assumption of validity for the overall measurement tool. Furthermore, reliability can be confirmed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. If the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is generally greater than 0.6, the reliability of the variables can be interpreted as robust (Hair et al., 2016). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was greater than 0.6 for each category of variables, demonstrating that the reliability of all variables was robust. The detailed information on the analysis contents is shown in Table 3 below.

Table 4 demonstrates that stakeholders and social capital among residents are well-established in both Handong-ri and Jeoji-ri because these two villages scored more than three points for village leader (3.64), trust (3.16), young residents (3.13) and participation (3.03). Correlation analysis and multiple regression models were conducted to further explore the relationships between participation, trust, networking, stakeholders and heritage.

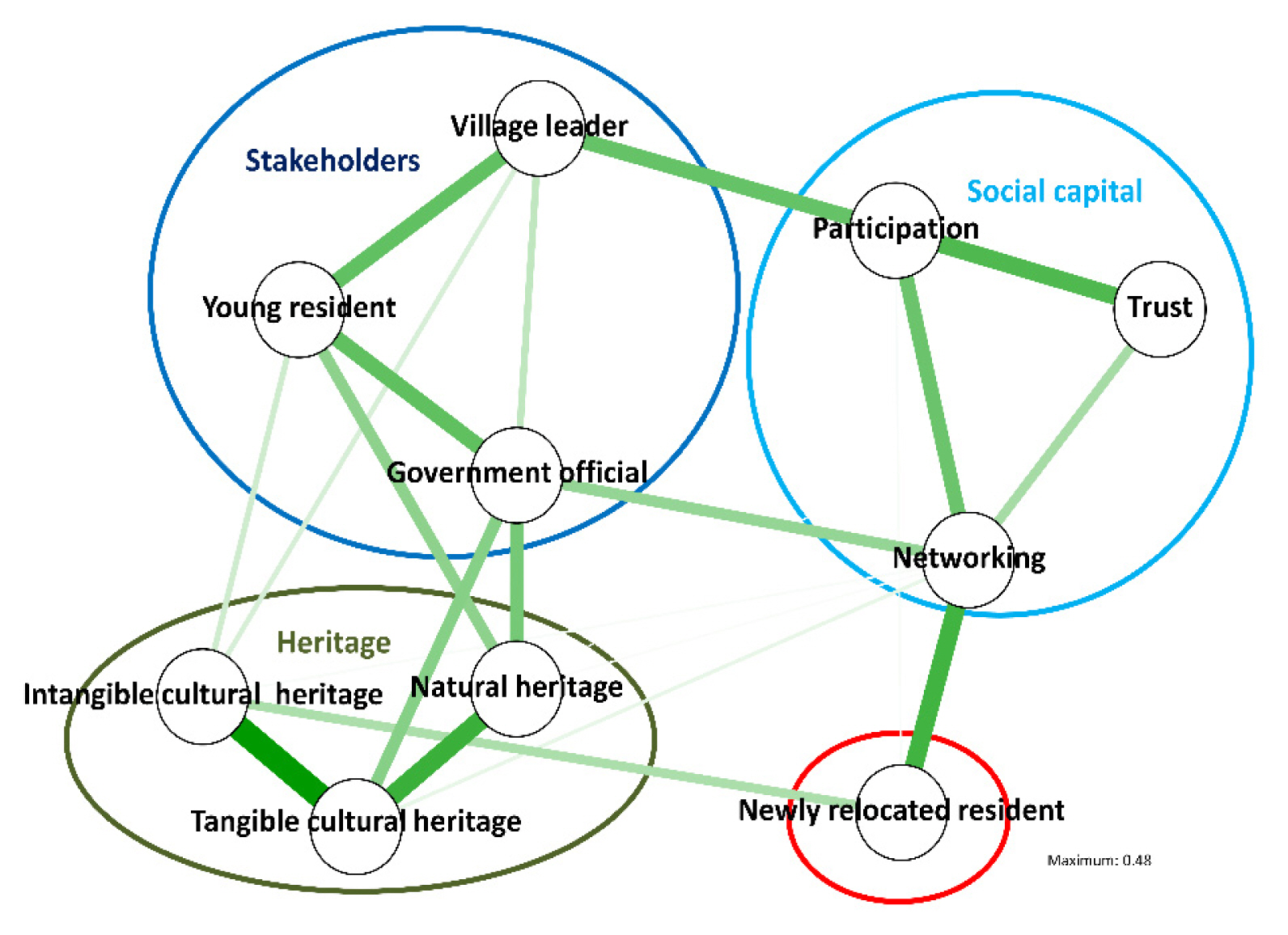

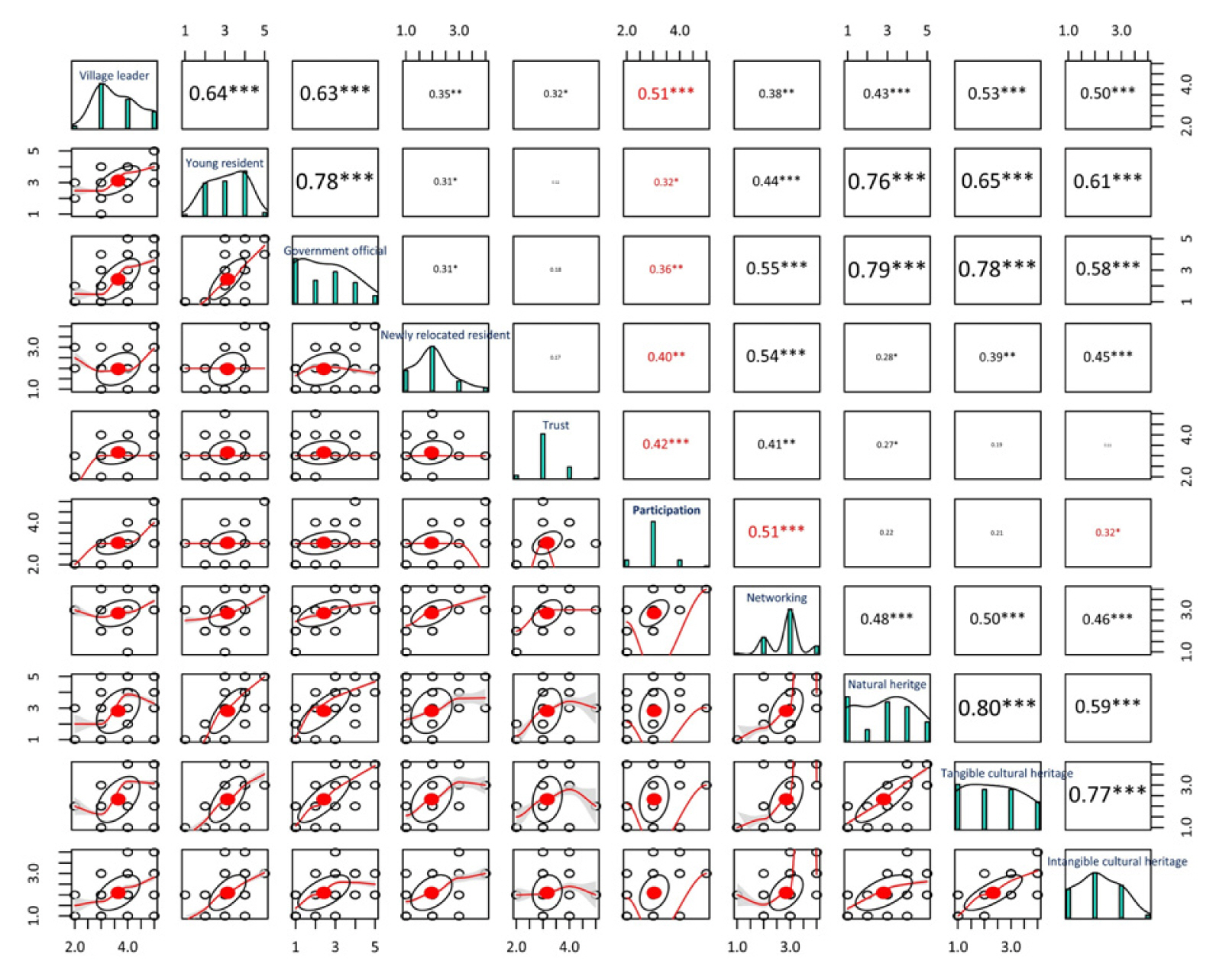

In analysing the relationship between participation and other variables, the village leader variable appears to have the most significant influence (0.51) on the participation variable (Fig. 4). Following the village leader variable, networking (0.50), trust (0.42), newly relocated residents (0.40), government officials (0.36), young people (0.32) and intangible cultural heritage (0.32) are positively correlated with the participation variable as illustrated in Fig. 4. Therefore, the significant influence of the stakeholders and social capital (Fig. 4) could imply that resident participation is substantially influenced by relevant stakeholders and the social capital of residents.

Among the heritage types, natural and tangible cultural heritage types are closely correlated with the stakeholder of government officials, suggesting that central or local governments usually manage natural and tangible cultural heritages. However, intangible heritages had a higher correlation with young residents than with government officials. Furthermore, only intangible cultural heritages had a statistically significant positive correlation with resident participation (Fig. 4), implying that intangible cultural heritages—unlike natural and tangible cultural heritages—can directly influence the resident participation level.

The results of the correlation analysis reveal that stakeholders, social capital, and intangible cultural heritage all have a positive relationship with the resident participation level. This study illustrates the correlation results using the R programming language (Fig. 5) to better understand the multidimensional relationships between stakeholders, social capital and intangible heritages as they affect resident participation.

Fig. 5 presents the multidimensional relationship structure between stakeholders, social capital and heritage, indicating that resident participation is most closely related to the village leader, trust and networking variables. In addition, variables of similar types tend to be grouped together. However, the newly relocated resident variable is not highly correlated with any other stakeholder variable, implying that newly relocated residents do not successfully integrate into village communities consisting primarily of existing residents. The existence of newly relocated residents further indicates a clear difference from other stakeholder variables (Fig. 5), and the analysis based on the above correlation analysis has limitations when it comes to explaining causal relationships (Hill, 2015). Therefore, this study conducted a multiple regression analysis to better understand the relationships between the factors that affect resident participation.

Performing multiple regression analyses requires examining whether the collected data meet expectations regarding normality, independence and the absence of perfect multicollinearity. The normality of the data can be confirmed through tests of skewness and kurtosis, which are indicators of the extent to which the data distribution is dissimilar from a normal distribution. Generally, it is assumed that data forms a normal distribution when the skewness value is ≤ 3 and the absolute value of kurtosis is ≤ 8 or ≤ 10 (Kline, 2005). Table 4 reveals that all variables have an absolute value of ≤ 3 for skewness and absolute values of ≤ 8 or ≤ 10 for kurtosis, confirming the normality of the data (Kline, 2005).

In addition, the Durbin-Watson values, 2.122 and 2.202, show no presence of autocorrelation regarding the residuals because these values fall between 1.5 and 2.5, both of which confirm that this model is reliable (Nam et al., 2018). Finally, a collinearity test with independent variables was conducted to ensure robustness and reliability and reveal any correlation between independent variables. The variance inflation factor value of each independent variable was < 10, confirming that no such correlation exists (Sung and Ki, 2021). Thus, the author notes the robustness and reliability of this regression model, allowing this study to conduct a multiple regression analysis using the data collected from residents in both villages.

Furthermore, prior to performing a multiple regression analysis, this study undertook an independent two-sample t-test and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to explore whether the sex or age of the respondents influence the participation level (Table 5). Table 5 demonstrates that the sex or age of respondents do not statistically influence the level of resident participation.

The results of the multiple regression analysis, including and excluding newly relocated residents, are provided in Tables 6 and 7. Table 6 presents the multiple regression model analysis excluding newly relocated residents, revealing that networking and intangible heritages, such as rituals or a village’s oral traditions, positively influence the resident participation level.

In contrast, Table 7 presents the multiple regression model analysis results, including newly relocated residents. Only intangible cultural heritage positively influences resident participation, implying that the existing networks within village communities do not play a significant role in increasing newly relocated residents’ participation in community activities.

Therefore, these findings indicate that village leaders, young people, and government officials influence the networking and intangible heritage variables, ultimately affecting residents’ participation in their communities. Interestingly, intangible heritage is the only heritage-related variable that influences resident participation, whereas natural and tangible heritage types have no statistical influence.

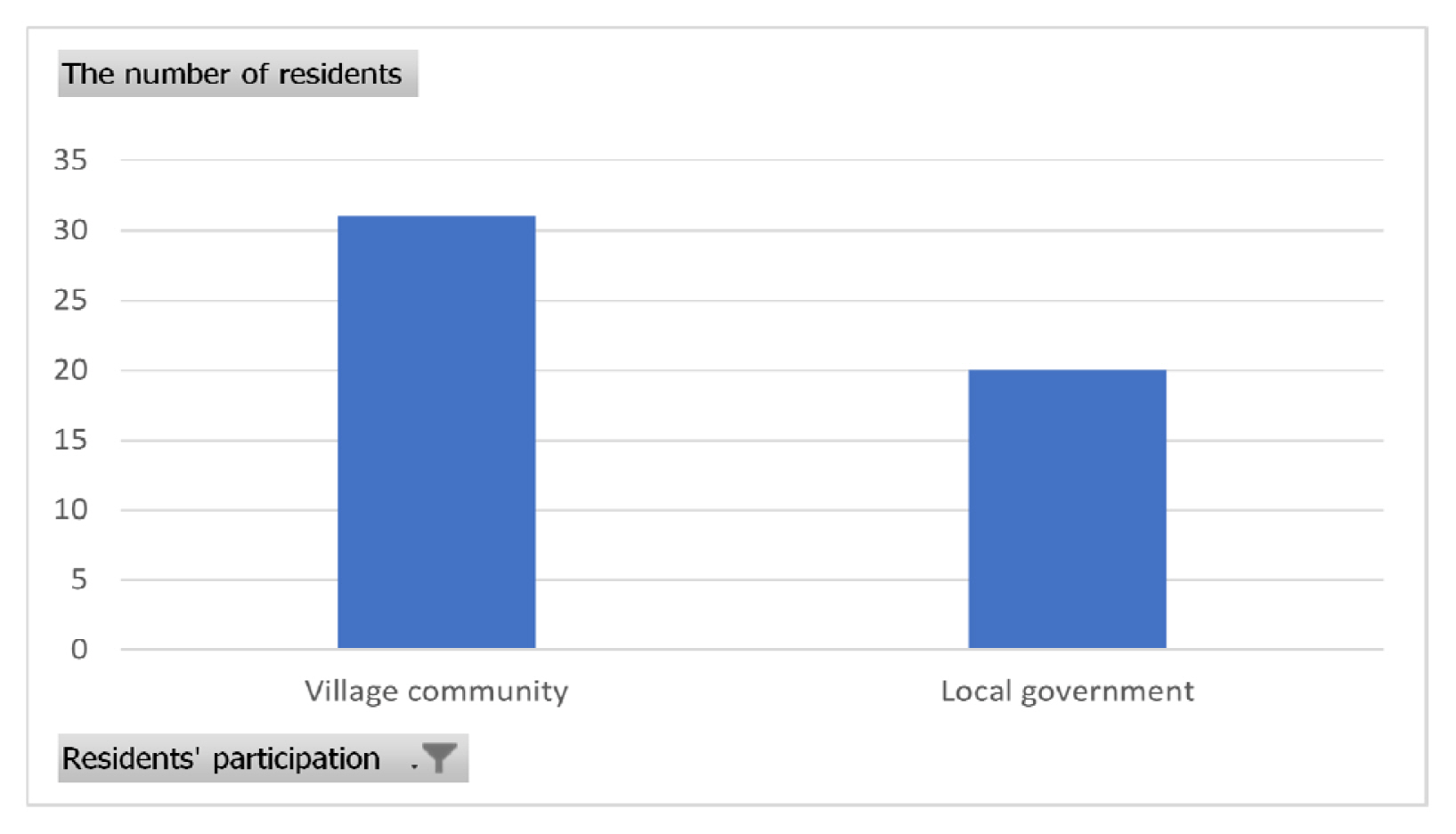

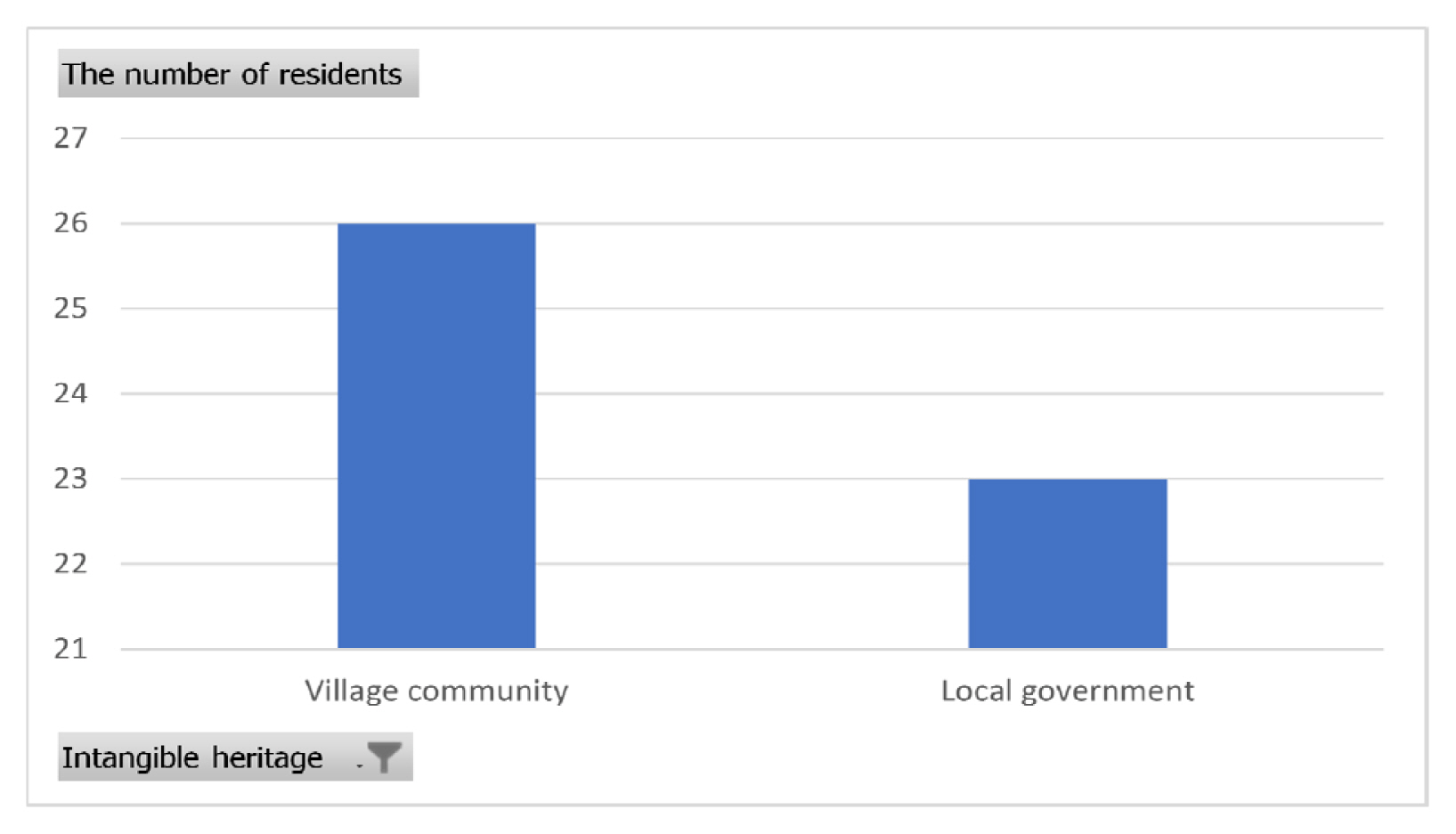

Additionally, residents were asked, ‘Who facilitates your participation in the community?’ Thirty-one residents (50%) reported that village communities drive resident participation, whereas 20 residents (32%) said that local governments are responsible for driving resident participation (Fig. 6). This finding indicates that village leaders and government officials play key roles as facilitators of resident participation.

The semi-structured interviews revealed that the most important role played by village leaders and government officials is networking. Village leaders form official and unofficial organisations to mediate conflicts between villagers, helping them cooperate with each other more effectively. Moreover, they often cooperate with higher-ranking government officials to secure government-funded development projects for their villages. During the semi-structured interview process, the head of Jeoji-ri suggested the following:

The head of the village works with local government officials to mediate conflicts between residents and attract government subsidy projects for the village. In addition, the government often plans local policies and projects through dialogue with village heads. The village community, with a focus on the village head, plays a key role in promoting the development of the village and residents’ participation in community activities (Kim. D.C., personal communication, September 9, 2020)

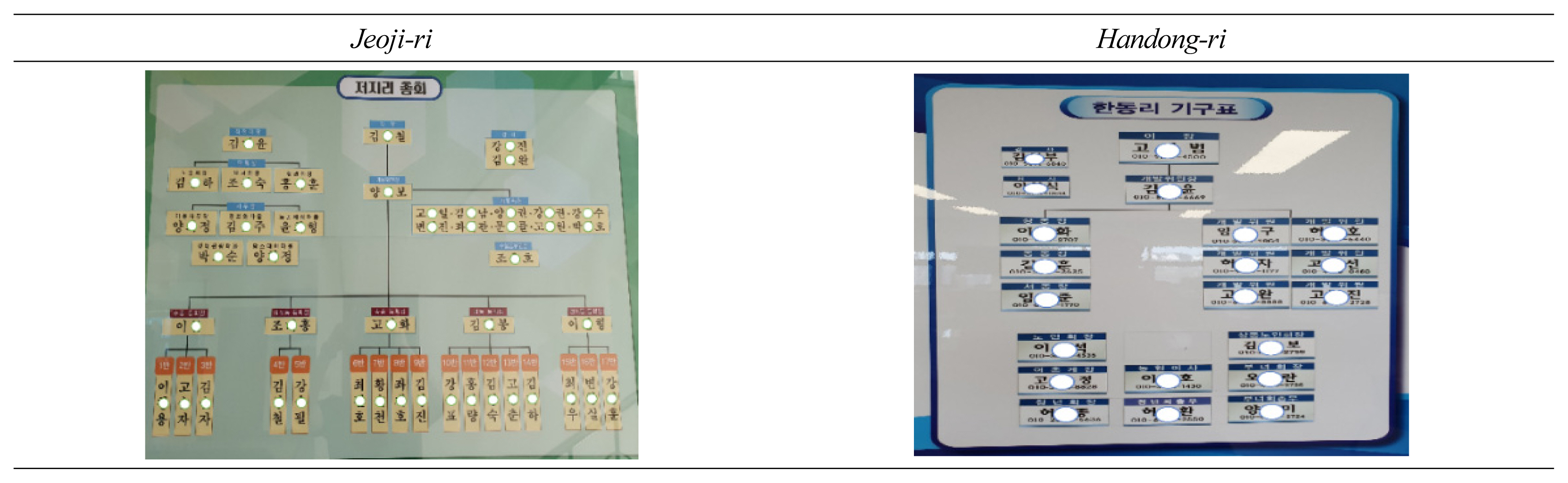

This close-knit networking structure can be observed in the communities of both villages (Fig. 7), and enables residents to actively participate in community activities and develop self-governing centres.

The formation of self-governing centres exemplifies their close-knit networking structures and increases voluntary resident participation. The village head and executives make decisions regarding village affairs and attract resident participation via this centre. The centre, whose operational costs are covered by fundraising events organised by residents, cooperates with local governments to serve as a bridge between residents and local government organisations because most of the work related to village administration is carried out there. As such, the village self-governing centre (Fig. 8) is where a close network between residents materialises as a place to promote their welfare and participation.

Yun and Yang (2014) also argue that the ‘ri’ community centre serves as a community hub where residents can meet and help each other deal with issues they face, thereby positively affecting network strength and the level of reciprocal trust. In addition, they highlighted the role of village leaders within the community centre as important stakeholders to improve the quality of residents’ lives by efficiently supporting the management of local cultural heritages (Yun and Yang, 2014).

Finally, 26 residents (42%) and 23 residents (37%) (a total of 49 residents (80%)) answered that the village’s intangible cultural heritage is managed by the village community and local governments, respectively (Fig. 9), a recognition of the importance of intangible heritages within their communities.

This result indicates that the village community or local government manages the intangible cultural heritage of the two villages as an important local cultural resource. In particular, intangible cultural heritages in both villages are well-established in the form of the village’s labour songs and ritual ceremonies, which are closely associated with the formation of a sense of community spirit among residents (Kim et al., 1994; Baek et al., 2001) because residents gathered to pray for the well-being of the village and the safety and prosperity of the villagers around heritage sites associated with intangible cultural heritages (Ko, 2019). Consequently, residents’ participation is increased by this strong sense of community spirit formed through intangible cultural heritages.

Previous studies related to Jeju Island have also demonstrated that intangible cultural heritages, primarily consisting of various local village rituals and oral traditions, have strengthened the sense of community spirit (Kang and Lee, 2015), thereby leading to positive effects in terms of resident participation (Kim, 2003; Yang and Kang, 2008). For example, Yang and Kang (2008) revealed that intangible cultural heritages play a role in strengthening the sense of community among residents on Jeju Island. Moreover, Jang and Lee (2001) indicated that their sense of community is positively related to resident participation in community activities. Thus, Kang and Lee (2015) argued that intangible heritages could be used to form a sense of community and thereby encourage voluntary resident participation.

This study builds on one finding of previous studies, which is that the promotion of resident participation is challenging at the practical level because engaging with residents and increasing their participation is a highly complex issue (Cuthill and Fein, 2005; Perkin, 2010). Chirikure et al. (2010) argued that the discourse of resident participation is rather ambitious in its intent from a practical perspective, claiming that local contexts determine the nature of resident participation. Thus, Taberner (2021) noted that an in-depth analysis should be conducted considering the particular regional context and stakeholders in terms of how to draw on voluntary resident participation to overcome the difficulties of promoting such participation.

In this context, this study selected two villages—Jeoji-ri and Handong-ri, both located on Jeju Island—as representative cases with active resident participation to explore the mechanism of active voluntary resident participation with a focus on heritage, social capital and the dynamic structure of stakeholder relationships, as highlighted in previous studies (Reddel and Woolcock, 2004; Perkin, 2010; Coningham and Lewer, 2019; UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2020). While considering the need for a practical approach regarding the lack of resident participation, this study provides a theoretical background to demonstrate that resident participation can be increased through networking among residents and intangible heritages.

The major outcomes and implications of this study can be summarised as follows. First, this study is important because it analyses the manner in which relevant stakeholders influence resident participation, as highlighted in previous research (Reddel and Woolcock, 2004; Perkin, 2010; Coningham and Lewer, 2019). This analysis concludes that village leaders, government officials and young residents all have a significant positive influence on networking among residents. Notably, only village leaders are also positively associated with trust among residents (Fig. 4), implying that village leaders are the most important stakeholders in fostering community participation. Village leaders frequently address potential issues arising within their communities and work with government officials on development plans (Ki et al., 2020), making them fundamental to aiding voluntary networking among residents. Thus, policy measures that facilitate voluntary resident participation should ensure support for village leaders.

Second, the research indicates that networking among residents effectively increases their participation (Fig. 4 and Table 6), a finding consistent with that of previous studies (Landorf, 2009; Perkin, 2010; Jaafar et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020). Grassroots resident participation fostered via networking can eliminate the exclusion of socially marginalised groups and improve the understanding of local needs, reinforcing the community’s cultural traditions (Yung, Zhang, and Chan, 2017). For example, Jaafar et al. (2015) highlighted that networking among residents is essential for engendering their active engagement in promoting and supporting their local cultural heritage sites.

Networking tools can be categorised in numerous ways, such as meetings, workshops, public media and social networking services (Timothy and Tosun, 2003; MacRae, 2017; Chinyele and Lwoga, 2018; Ferreira, 2018). MacRae (2017) and Chinyele and Lwoga (2018) highlighted public meetings as a platform where community members can discuss various issues on the social agenda and share responsibilities concerning their heritage sites. Ferreira (2018) suggested that workshops can be useful for educating residents in conservation theories and technologies, thereby providing a foundation for effectively fostering resident participation in heritage management (UNESCO, 2019b). Furthermore, Timothy and Tosun (2003) suggested using public media to raise awareness of cultural heritage sites among residents.

Various networking channels enable resident participation (Hung et al., 2011). For example, Jeoji-ri successfully developed its community using social networking services, such as Naver Band. Establishing connections and sustaining interactions between residents using the internet is particularly important for creating strong bonds and relationships among people, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Quan-Haase et al. (2002) acknowledged that digital networking tools also help develop a sense of belonging within online communities, and thus can successfully facilitate resident participation.

Finally, the intangible cultural heritage of both villages enables resident participation. The findings indicate that the intangible cultural heritage of a village helps form a sense of community among its residents, enabling them to actively participate in their respective village communities (Yang and Kang, 2008; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Jeju Special Self-governing Province, 2019). Thus, by using intangible cultural heritages such as village festivals, village communities or local governments can enable both existing and newly relocated residents to understand the village’s history and traditions and develop a sense of community, which ultimately positively influences the overall resident participation level. Key stakeholders should carefully manage this utilisation of intangible heritage to include newly relocated residents in the process so that local communities do not exclusively emphasise the role played by existing residents (Kim et al., 2021).

This study identifies the factors affecting Jeju Island’s resident participation and provides insights relevant to the Korean government’s recently published five-year plan (2018–2022) for balanced national development (Presidential Committee for Balanced National Development, 2020). This policy focuses on heritage-driven place-branding, particularly for places where the population has diminished over time, in order to develop more desirable living environments for residents. Motivating voluntary resident participation is essential for the success of this plan (Ha, 2020).

Despite the potential importance of the current study, the limitations of this research must be acknowledged. First, as this study was undertaken using a small number of residents due to restrictions related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, future follow-up studies could consider conducting a time-series analysis to build on these findings. Second, this study was based on two case studies of villages located on Jeju Island, and key stakeholders, social capital and heritage can vary distinctly depending on the situations in each village (Coningham and Lewer, 2019; Ranwa, 2021). Therefore, future research should examine the characteristics of villages in various other regions to build upon the present findings. Finally, the tangible cultural heritages associated with the intangible cultural heritages on Jeju Island are currently being damaged by disasters and inadequately controlled development (Yonhap News Agency, 2021). In addition, the current archiving of intangible heritage projects has limitations because of the government’s top-down documentation systems, which fail to include contextual information such as community identity and history (Kim and Lee, 2018). Thus, to lay a strong foundation for future effective use and to promote resident participation by utilising intangible cultural heritages as described in this study, follow-up studies should consider how intangible heritages can be recorded appropriately to prevent their loss and preserve them for future generations.

Notes

This research paper employs the data I have collected for writing the report titled ‘Current Status and Challenges of Resource Management and Utilization in Rural Villages’, which was funded by Korea Rural Economic Institute Furthermore, this paper is based on my internal student reports at Durham University and my master’s dissertation at Myongji University. I would like to thank Professor Junghoon Ki at Myongji University—my project advising professor—for his support and guidance during my research. In addition, I want to acknowledge the constructive comments of Associate Professor Mary Brooks at Durham University.

Fig. 2

Aerial image of Jeoji-ri and Hangdong-ri with the administrative boundaries. Google Earth (2021) Jeju Island. Available at https://earth.google.com/web/ (Accessed: 7 March 2021).

Fig. 4

Results of the correlation analysis. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 (levels representing statistical significance).

Fig. 6

Awareness of residents regarding drivers of resident participation. The author analysed the primary data focusing on who facilitates resident participation.

Fig. 7

Close-knit network structures in both villages (photographed by the author, 2020). Parts of the images have been deliberately covered to protect the anonymity of the participants.

Fig. 9

Residents’ awareness regarding intangible heritage. he author analysed the primary data with a focus on how residents perceive their intangible heritage.

Table 1

Data characteristics

| Village | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Handong-ri | 19 (67%) | 14 (42%) |

| Jeoji-ri | 9 (33%) | 19 (58%) |

| Total | 28 (100%) | 33 (100%) |

Table 2

Operational definition and implication for each variable of analysis

| Definition | Variables | Components | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage | Natural heritages (UNESCO, 2019b) | Natural sites with cultural aspects, such as cultural landscapes and physical, biological or geological formations | |

| Tangible cultural heritages (UNESCO, 2019b) | Monuments, groups of buildings and physical sites | ||

| Intangible cultural heritages (UNESCO, 2019b) | Oral traditions, performing arts, rituals and traditional village festivals | ||

| Stakeholders | Newly relocated resident (Chilvers and Kearnes, 2016) | A person who voluntarily migrates to a rural village and is different from existing residents (Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, 2020) | |

| Village leader (Perkin, 2010) | A person who personally or collectively influences residents to follow a common goal or direction (Choi and Kim, 1994) | ||

| Young resident (Jaafar et al., 2015) | A young person (15 years or older) who is an engaged member of the working population (Statistics Korea, 2022) | ||

| Government official (Li et al., 2020) | A person employed by a government organisation to perform public duties or work at a village self-governing centre | ||

| Social capital | Participation (Thomas and Lea, 2014) | Participation in community events, various community organisations and degree of communal use of public facilities (So, 2014) |

Achieving a common goal within a community (So, 2014) |

| Networking (Li et al., 2020) | Official and unofficial community organisations, the scope of the neighbourhood concerning resident perception and the degree to which there is a support system if needed (So, 2014) |

Maintaining neighbourhoods and communities (So, 2014) |

|

| Trust (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017) | Familial trust, trust in commercial transactions and trust in public policy (So, 2014) |

Securing a common foundation for a community (So, 2014) |

|

Table 3

Principal factor analysis and reliability analysis regarding each category of variables

| Category | Variables | Component loading | Eigen value | Variance ratio | KMO | Bartlett’s x2 | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage | Natural heritage | 0.885 | 2.45 | 81.7 | 0.656 | 113*** | 0.864 |

| Tangible cultural heritage | 0.954 | ||||||

| Intangible cultural heritage | 0.871 | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Stakeholders | Village leader | 0.840 | 2.57 | 64.2 | 0.751 | 97.1*** | 0.799 |

| Young resident | 0.887 | ||||||

| Government official | 0.886 | ||||||

| Newly relocated resident | 0.539 | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Social capital | Trust | 0.747 | 1.88 | 62.6 | 0.663 | 30.3*** | 0.698 |

| Participation | 0.808 | ||||||

| Networking | 0.816 | ||||||

Table 4

Basic statistics for independent and dependent variables

Table 5

Results of the independent two sample t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Table 6

Results of the multiple regression model excluding newly relocated residents

| Dependent variable | Independent variables | Nonstandardised coefficient | Standardised coefficient | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| B | ß | T | ||||

| Participation | Constant | 0.962 | 2.339* | |||

| Village leader | 0.205 | 0.314 | 1.882 | 0.369 | 2.708 | |

| Young people | −0.080 | −0.137 | −0.663 | 0.241 | 4.154 | |

| Government official | 0.143 | 0.348 | 1.447 | 0.178 | 5.616 | |

| Trust | 0.211 | 0.215 | 1.691 | 0.638 | 1.567 | |

| Networking | 0.250 | 0.295 | 2.172* | 0.560 | 1.785 | |

| Natural heritage | −0.72 | −0.188 | −0.742 | 0.160 | 6.244 | |

| Tangible cultural heritage | −0.219 | −0.442 | −1.800 | 0.171 | 5.850 | |

| Intangible cultural heritage | 0.259 | 0.399 | 2.244* | 0.326 | 3.068 | |

|

|

||||||

| Model | F(p) = 5.885***, R2 = 0.485, Adj. R2 = 0.403, Dublin-Watson = 2.122 | |||||

Table 7

Results of the multiple regression model including newly relocated residents

| Dependent variable | Independent variables | Nonstandardised coefficient | Standardised coefficient | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| B | ß | T | ||||

| Participation | Constant | 0.978 | 2.373* | |||

| Village leader | 0.193 | 0.110 | 1.759 | 0.364 | 2.745 | |

| Young people | −0.077 | 0.122 | −0.636 | 0.241 | 4.158 | |

| Government official | 0.151 | 0.099 | 1.518 | 0.177 | 5.656 | |

| Newly relocated resident | 0.085 | 0.091 | 0.936 | 0.606 | 1.650 | |

| Trust | 0.219 | 0.125 | 1.747 | 0.636 | 1.573 | |

| Networking | 0.199 | 0.127 | 1.558 | 0.457 | 2.187 | |

| Natural heritage | −0.063 | 0.098 | −0.647 | 0.159 | 6.303 | |

| Tangible cultural heritage | −0.229 | 0.112 | −1.876 | 0.170 | 5.898 | |

| Intangible cultural heritage | 0.237 | 0.122 | 2.006* | 0.313 | 3.198 | |

|

|

||||||

| Model | F(p) = 5.316***, R2 = 0.494, Adj. R2 = 0.401, Dublin–Watson = 2.202 | |||||

References

Baek, SJ, MC Kim, MS Kang. 2001. ‘北濟州郡 翰京面 楮旨里: 信仰’ [Northern Jeju-gun Hankyung-eup Jeoji-ri: Religion]. 國文學報 [Korean Literature Academic Report]. 15(524):224-272. Retrieved from oak.jejunu.ac.kr/handle/2020.oak/3098

Brown, R 2017. Durham castle and cathedral world heritage site management plan 2017–2023 Durham, UK: Durham Cathedral. Retrieved from https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/files/Durham%20WHS%20Management%20Plan%202017.pdf

Chilvers, J, M Kearnes. 2016. Remaking participation: towards reflexive engagement Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Chinyele, BJ, NB Lwoga. 2018. Participation in decision making regarding the conservation of heritage resources and conservation attitudes in Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. 9(2):184-198.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-05-2017-0019

Chirikure, S, M Manyanga, W Ndoro, G Pwiti. 2010. Unfulfilled promises? heritage management and community participation at some of Africa’s cultural heritage sites. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16(1–2):30-44.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441739

Choi, JY, HS Kim. 1994. Group and Leadership Seoul, South Korea: Yupung Publisher.

In: Coningham R, Lewer N, 2019. (Eds), Archaeology, cultural heritage protection and community engagement in South Asia London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cuthill, M, J Fein. 2005. Capacity building: facilitating citizen participation in local governance. Australian Journal of Public Administration. 64(4):63-80.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2005.00465a.x

Fan, L 2014. International influence and local response: understanding community involvement in urban heritage conservation in China. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 20(6):651-662.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.834837

Ferreira, TC 2018. Bridging planned conservation and community empowerment: Portuguese case studies. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. 8(2):179-193.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-05-2017-0029

Ha, JH 2020 October 26 Residents’ participation should be based on activation of agricultural and fishing villages. The Farmers Newspaper Retrieved from https://www.nongmin.com/news/NEWS/POL/ETC/328199/view

.

Hair, JF, WC Black, BJ Babin, RE Anderson, RL Tatham. 2006. Multivariate date analysis London, UK: Pearson.

Hill, AB 2015. The environment and disease: association or causation? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 108(1):32-37.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814562718

Historic England. 2020 Heritage at risk 2020 registers London, UK. Historic England; Retrieved from https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/har-2020-registers/

.

Historic England. 2005 Understanding historic landscapes: sharing knowledge across boundaries London, UK. European and World Perspectives; Retrieved from https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-bulletin-50/

.

Hung, K, E Sirakaya-Turk, LJ Ingram. 2011. Testing the efficacy of an integrative model for community participation. Journal of Travel Research. 50(3):276-288.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362781

ICOMOS. 2008 ICOMOS charter for the interpretation and presentation of cultural heritage sites Quebec, Canada. Retrieved from http://icip.icomos.org/downloads/ICOMOS_Interpretation_Charter_ENG_04_10_08.pdf

.

Jaafar, M, SM Noor, SM Rasoolimanesh. 2015. Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: A case study of the Lenggong world cultural heritage site. Tourism Management. 48:154-163.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.018

Jang, JH, IH Lee. 2001. A study on the relationship between the sense of community and resident self-help activities. Journal of the Korean Urban Geographical Society. 4(2):15-26.

Jeju Special Self-governing Province. 2017 Ordinance for the Creation of a Community of Jeju Special Self-governing Province Settlers, c. 2 Sejong, South Korea. Retrieved from https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do

.

Jeju Special Self-governing Province. 2019 Folk and Culture Sejong; South Korea. Retrieved from https://www.jeju.go.kr/culture/folklore/religious/religious01.htm

.

Jimura, T 2011. The impact of world heritage site designation on local communities: a case study of Ogimachi, Shirakawa-mura, Japan. Tourism Management. 32(2):288-296.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.02.005

Kang, KH, JH Lee. 2015. An empirical study of the mediating effect of governance in relationship between resident participation and rural community design rroject performance: Focused on the case of Utturu village. Journal of Korean Society of Rural Planning. 21(1):103-115.

https://doi.org/10.7851/ksrp.2015.21.1.103

Ki, JH, HB Lim, HJ Chun, MK Sung, GH Park. 2020. Current status and challenges of resource management and utilization in rural villages Naju, South Korea: Korea Rural Economic Institute.

Kim, DJ 2003. The right understanding of Jeju cultures and its application plans-related to the period of Jeju free international city. Journal of Local History and Culture. 6(2):315-346.

https://doi.org/10.17068/lhc.2003.11.6.2.315

Kim, IW 2008. The advance of the outer forces into Jeju and Jeju women’s lives with them during the Goryeo and Joseon periods. The Journal for the Studies of Korean History. 32:143-172.

Kim, JH, YH Lee. 2018. A study on the documentation method of intangible cultural heritage and training center. The Korean Journal of Archival Studies. 56:147-182.

https://doi.org/10.20923/kjas.2018.56.147

Kim, JH, G Kim, HY Jung. 2021. Reflection of Kimhae multicultural locality: from the space of distinction to encounter. The Journal of Localitology. 25:119-160.

https://doi.org/10.15299/tjl.2021.4.25.119

Kim, TG, TG Choi, SS Mun, SS An, CS Yun, YJ Hyun, et al. 1994. 北濟州郡 舊左邑 漢東里 現地學術調 査報告 [Northern Jejugun Gujwa-eup Handong-ri on-site academic research report] Jeju City, South Korea: 白鹿語文 學會 [Baengnok Language Literature Academic Society].

Kline, TJ 2005. Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage Publications.

Ko, CS 2019 History of Jeju island Jeju Special Self-Governing Province; South Korea. Retrieved from https://www.jeju.go.kr/culture/history/period/period01.htm

.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2020 Heritage in urban contexts: impacts of development projects on world heritage properties in cities Fukuoka, Japan. Author; Retrieved from https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:R27GZU7GsmsJ:https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/1516/+&cd=13&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk

.

Landorf, C 2009. A framework for sustainable heritage management: a study of UK industrial heritage sites. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 15(6):494-510.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903210795

Landorf, C 2011. A future for the past: A new theoretical model for sustainable historic urban environments. Planning Practice & Research. 26(2):147-165.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2011.560458

Li, J, S Krishnamurthy, AP Roders, P van Wesemael. 2020. Community participation in cultural heritage management: a systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities. 96:102476.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102476

MacRae, G 2017. Universal heritage meets local livelihoods: awkward engagements’ at the world cultural heritage listing in Bali. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 23(9):846-859.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1339107

May, S 2020. Heritage, endangerment and participation: alternative futures in the Lake District. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 26(1):71-86.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1620827

Meissner, M 2021. The valorisation of intangible cultural heritage. Intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development New York City, USA: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79938-0_5

Millar, S 2005. The impact of world heritage sites on communities. Conservation Bulletin. 50:13.

Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. 2020 Framework act on agriculture, rural community and food industry Sejong, South Korea. MAFRA; Retrieved from https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do

.

Mydland, L, W Grahn. 2012. Identifying heritage values in local communities. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 18(6):564-587.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.619554

Nam, JN, HS Lee, I Heo. 2018. Econometrics Seoul, South Korea: Hongmoonsa Publisher.

National Trust. 2020 For everyone, for ever: our strategy to 2025 Swindon, UK. Retrieved from https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/for-everyone-for-ever-our-strategy-to-2025

.

No, WJ 2021. Ecological sustainability of Jeju sea and the role of Jeju Haenyeo’s community. Master’s dissertation. Jeju National University, South Korea.

Pearce, PL, G Moscardo, GF Ross. 1996. Tourism community relationships Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Perkin, C 2010. Beyond the rhetoric: negotiating the politics and realising the potential of community-driven heritage engagement. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16(1–2):107-122.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441812

Poulios, I 2014. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. 4(1):16-34.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-10-2012-0048

Presidential Committee for Balanced National Development. 2020 2020 Vision and Value Sejong, South Korea. PCBND; Retrieved from http://www.balance.go.kr/base/contents/view?contentsNo=27&menuLevel=2&menuNo=52

.

Puddifoot, JE 2003. Exploring “Personal” and “Shared” sense of community identity in Durham City, England. Journal of Community Psychology. 31(1):87-106.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10039

Quan-Haase, A, B Wellman, JC Witte, KN Hampton. 2002. Capitalizing on the net: social contact, civic engagement, and sense of community. In: Werry B, Haythornthwaite C, (Eds), The Internet in Everyday Life (pp. 291-324). NJ, USA: Blackwell.

Ranwa, R 2021. Heritage, community participation and the state: case of the Kalbeliya dance of India. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 27(10):1-13.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1928735

Rasoolimanesh, SM, M Jaafar, AG Ahmad, R Barghi. 2017. Community participation in world heritage site conservation and tourism development. Tourism Management. 58c:142-153.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.016

Rasoolimanesh, SM, M Jaafar, N Badarulzaman, T Ramayah. 2015. Investigating a framework to facilitate the implementation of city development strategy using balanced scorecard. Habitat International. 46:156-165.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.12.003

Reddel, T, G Woolcock. 2004. From consultation to participatory governance? a critical review of citizen engagement strategies in Queensland. Australian Journal of Public Administration. 63(3):75-87.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2004.00392.x

Schmidt, PR 2014. Community heritage work in Africa: village-based preservation and development. Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage. 14(2):133-150.

So, JG 2004. The logic of connecting local autonomy system with regional development through accumulating social capital. The Korea Local Administration Review. 18(2):67-91.

Song, MY, JI Sung, IC Han, KC Min. 2020 A panel survey for rural villages Naju, South Korea. Korea Rural Economic Institute; Retrieved from http://www.krei.re.kr/krei/researchReportView.do?key=67&pageType=010101&biblioId=527428&pageUnit=10&searchCnd=all&searchKrwd=&pageIndex=1

.

Song, SS, BS Han. 2012. Relationship between community attachment and participation intention to endogenous community tourism development in Jeju. Journal of Tourism Sciences. 36(1):241-261.

Statistics Korea. 2022 Economically active population Daejeon, South Korea. Statistics Korea; Retrieved from https://kostat.go.kr/understand/info/info_lge/1/detail_lang.action?bmode=detail_lang&pageNo=2&eyword=0&cd=SL3966&sTt=

.

Sung, MK, JH Ki. 2021. Influence of educational and cultural facilities on apartment prices by size in Seoul: do residents’ preferred facilities influence the housing market? Housing Studies. Advanced Online Publication. 1-27.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1908962

Taberner, S 2021. Heritage and our sustainable future Retrieved from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Funesco.org.uk%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F05%2FBiocultural-Heritage-and-Landscapes-Linking-Nature-and-Culture.pdf&clen=3703223&chunk=true

The Ministry of the Interior and Safety. 2021 Special act on the establishment of Jeju Special Self-Governing Province and the development of free international city Retrieved from https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engMain.do

.

In: Thomas S, Lea J, 2014. (Eds), Public participation in archaeology Rochester, New York, USA: Boydell & Brewer.

Timothy, D, C Tosun. 2003. Appropriate planning for tourism in destination communities: participation, incremental growth and collaboration. In: Singh S, Timothy D, Dowling R, (Eds), Tourism in destination communities (pp. 181-204). Wallingford, UK: CABI Publisher.

UNESCO. 2019a The UNESCO recommendation on the historic urban landscape Paris. UNESCO World Heritage Centre; Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/

.

UNESCO. 2019b Operational guidelines for the implementation of the world heritage convention Paris. UNESCO World Heritage Centre; Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/

.

Vollero, A, F Conte, G Bottoni, A Siano. 2018. The influence of community factors on the engagement of residents in place promotion: empirical evidence from an Italian heritage site. International Journal of Tourism Research. 20(1):88-99.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2164

Waterton, E, L Smith. 2010. The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 16(1–2):4-15.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441671

Yang, DS, YS Kang. 2008. Resident participation raises local community consciousness, which is vital. Journal of Local Government Studis. 20(1):71-89.

Yonhap News Agency. 2021 August 1 Jeju’s shrine is groaning from disasters and difficulties caused by typhoons. Maeil Business Newspaper Retrieved from https://www.mk.co.kr/news/culture/view/2021/08/741770/

.

Yun, WS, DS Yang. 2014. A study on the influence of satisfaction of community center participation on local social capital: focusing on Jeju Special Self-governing Province. Tamla Culture. 45:57-86.

https://doi.org/10.35221/tamla.2014..45.003

Yung, EHK, Q Zhang, EHW Chan. 2017. Underlying social factors for evaluating heritage conservation in urban renewal districts. Habitat International. 66:135-148.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.06.004

Zhang, R, S Brown. 2022. Benefit or burden? The world heritage listing of Libo Karst, China. International Journal of Heritage Studies. Advanced Online Publication. 1-19.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.2025144

Zhong, X, H Leung. 2019. Exploring participatory microregeneration as sustainable renewal of built heritage community: two case studies in Shanghai. Sustainability. 11(6):1617-1632.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061617

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 2 Crossref

- 4,584 View

- 83 Download

- Related articles in J. People Plants Environ.