|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 25(1); 2022 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: The benefits of green spaces are starting to be recognized, particularly after the emergence of COVID-19. However, only well-managed green spaces deliver positive benefits. To maintain green spaces, various assessment tools have been developed. The Green Flag Award (GFA), which is the UKŌĆÖs national audit tool, is focused on the structure and criteria of green spaces assessment. However, we do not know about the changes that drive our understandings of well-managed green spaces, impacts of the GFA, or changes in other assessment tools. Therefore, the aim of this study is to understand the changes that drive the development of green space assessment tools, with a focus on the GFA, to deliver a framework for the long-term management of these spaces.

Methods: This study employed the Protocol and Reporting result with Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis (PSALSAR) and Develop frameworks, as well as the assessment-focused place-keeping analytical framework. The PSALSAR framework was used to ensure accuracy, systematisation, exhaustiveness, and reproducibility. The assessment-focused place-keeping analytical framework was employed to understand the contribution of green space assessment tools in the long-term management of these spaces.

Results: First, well-managed green spaces (GS) were positively associated with quality of life, which is a widely known fact. However, the approach to managing GS in the long term is a key issue. Second, the GFA had great impacts on the ability to manage GS well by providing developed domains and reflecting contemporary GS issues. Third, drivers of GS assessment tools include the persistence and importance of conventional maintenance, emphasis on accessibility by expanding practical boundaries, the inevitability of enhancing community involvement, and diversity of involvement in the judging process. Lastly, assessment-focused, place-keeping analytical frameworks imply that approaches to long-term management should be contextualised based on policy, funding, governance, partnership, and maintenance.

Conclusion: Understanding changes that drive GS assessment and its association with GS management should be prioritised. This study concludes that approaches to GS assessment should be framed in the context of long-term management, underscored by understanding contemporary GS issues.

Methods: This study employed the Protocol and Reporting result with Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis (PSALSAR) and Develop frameworks, as well as the assessment-focused place-keeping analytical framework. The PSALSAR framework was used to ensure accuracy, systematisation, exhaustiveness, and reproducibility. The assessment-focused place-keeping analytical framework was employed to understand the contribution of green space assessment tools in the long-term management of these spaces.

Results: First, well-managed green spaces (GS) were positively associated with quality of life, which is a widely known fact. However, the approach to managing GS in the long term is a key issue. Second, the GFA had great impacts on the ability to manage GS well by providing developed domains and reflecting contemporary GS issues. Third, drivers of GS assessment tools include the persistence and importance of conventional maintenance, emphasis on accessibility by expanding practical boundaries, the inevitability of enhancing community involvement, and diversity of involvement in the judging process. Lastly, assessment-focused, place-keeping analytical frameworks imply that approaches to long-term management should be contextualised based on policy, funding, governance, partnership, and maintenance.

Conclusion: Understanding changes that drive GS assessment and its association with GS management should be prioritised. This study concludes that approaches to GS assessment should be framed in the context of long-term management, underscored by understanding contemporary GS issues.

Today, green spaces significantly contribute to peopleŌĆÖs quality of life given their positive effects on mental health (Nam and Kim, 2021), stress relief (Grahn and Stigsdotter, 2010), and abatement of mental fatigue (Kaplan, 2001), thus improving overall health and increasing physical activity levels (Nam and Dempsey, 2019a). In addition, urban green spaces can hold potential benefits across a wide range of environmental issues, such as leading to improvements in the local climate and air quality (Pugh et al., 2012), carbon sequestration (Townsend-Small and Czimczik, 2010), and supporting biodiversity through habitat provision (Sandstr├Čm et al., 2006). However, the statements above are not always the case that well-managed green spaces can deliver these benefits unless poorly managed green spaces result in undesirable effects, such as anti-social behaviours and vandalism, as well as serious crimes (European Commission, 2010). Further, it is not enough to understand why green spaces should be well-managed and what the associated impacts are. In terms of the importance of well-managed green spaces, many assessment tools examining green space management have been developed and implemented around the world. Indicators and domains have been widely introduced, reflecting the paradigm shift toward the need to manage green spaces well. In particular, a national assessment tool for green spaces called the Green Flag Award (GFA), which was introduced in the UK and is employed in several countries, has been highlighted as a representative audit tool. The tool has made great contributions to the long-term management of green spaces and has improved the overall quality of these spaces (Nam and Dempsey, 2019a). However, we do not know about the strong impacts of GFA in terms of its contributions to managing these spaces well. In addition, increasing the numbers of countries to adopt national and local green spacesŌĆÖ assessment tools have referred and benchmarked to the structure and domains of GFA (Nam and Kim, 2019a). Furthermore, several countries, e.g., the European Union (EU), United Arab Emirates, Australia, New Zealand, and others, have already acquired the license for GFA from Keep Britain Tidy, or are currently in the process of doing so. This means that GFA provides standards for changes in the assessment of green spaces, reflecting contemporary trends for green space management. Given the importance of green space assessments and GFA, increasing numbers of green space assessment tools have been established in the UK, EU, USA, and Australia. As such, further studies are needed to better understand the drivers of change in green space assessment tools, while focusing on the GFA. The findings from these studies will ultimately provide keys to framing the ongoing and proper management of green spaces with positive benefits in the long term.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to understand the drivers of change of green space assessment tools, focusing on the GFA. To address this aim, the objectives of this study were as follows: 1) to review the meaning of well-managed green spaces; 2) to explore the GFA and its positive impacts; 3) to understand a wide range of assessment tools and their drivers of change; and 4) to rethink assessment-focused green space processes to achieve long-term positive benefits.

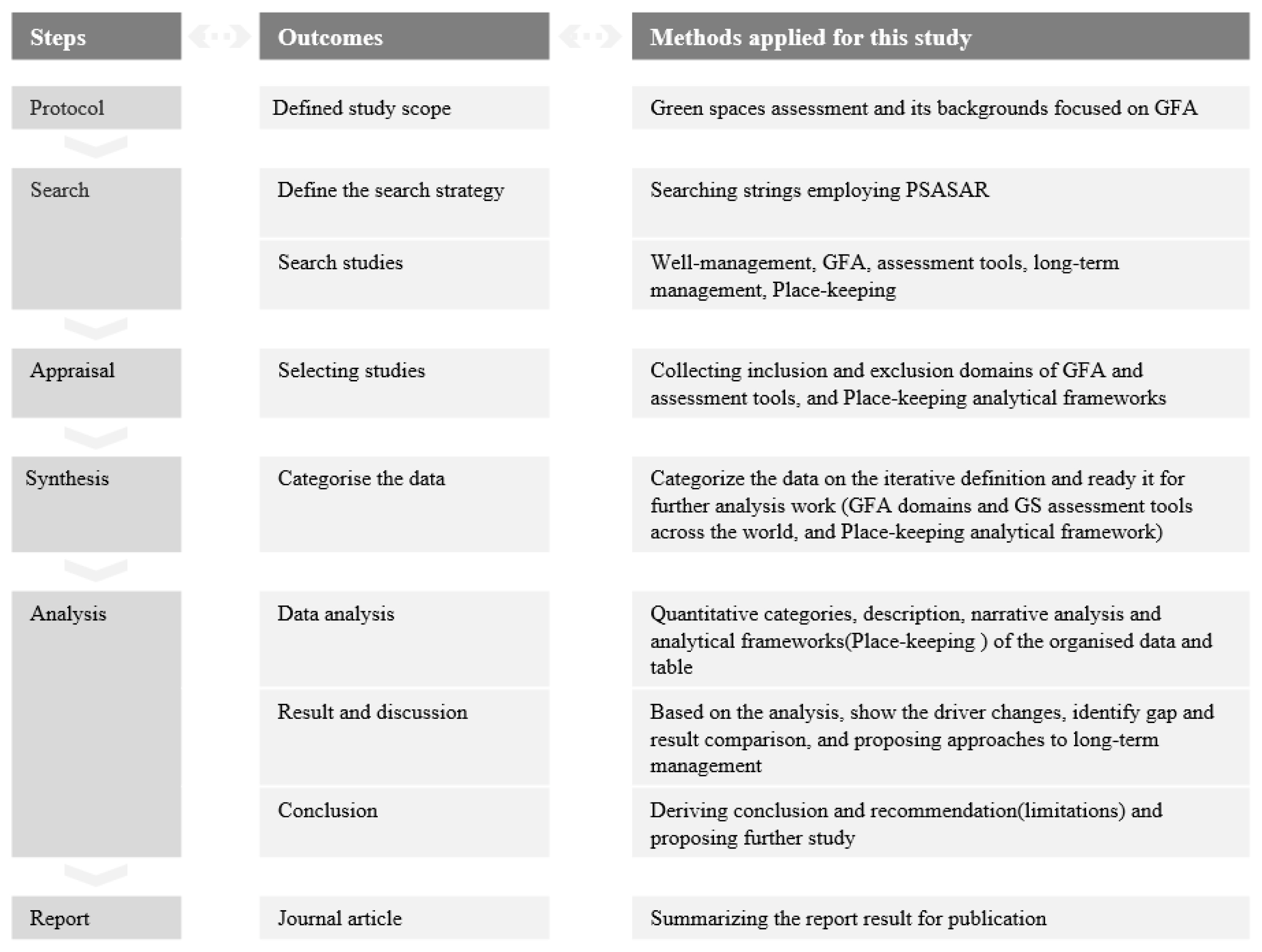

To address the aim of this study, this study employed the Protocol and Reporting results with Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis framework, and the Develop (PSALSAR) framework. PSALSAR originated from the Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis (SALSA) framework (Grant and Booth, 2009), which aids in the development of search protocols for systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. This methodological approach was used to ensure methodological accuracy, systematisation, exhaustiveness, and reproducibility (Mengist et al., 2020). To explore and understand specific issues and to develop the knowledge base for this study, the PSALSAR framework was used (Fig. 1).

As green space assessment tools are generally utilised in practice, the grey literature was also collected. Email-based collection was also conducted during the search process and were collected when data were unavailable in open sources. Eighteen tools in total were collected across the UK, EU, USA, and Australia. Several tools not targeting public green spaces or parks were excluded from the appraisal step (Table 1).

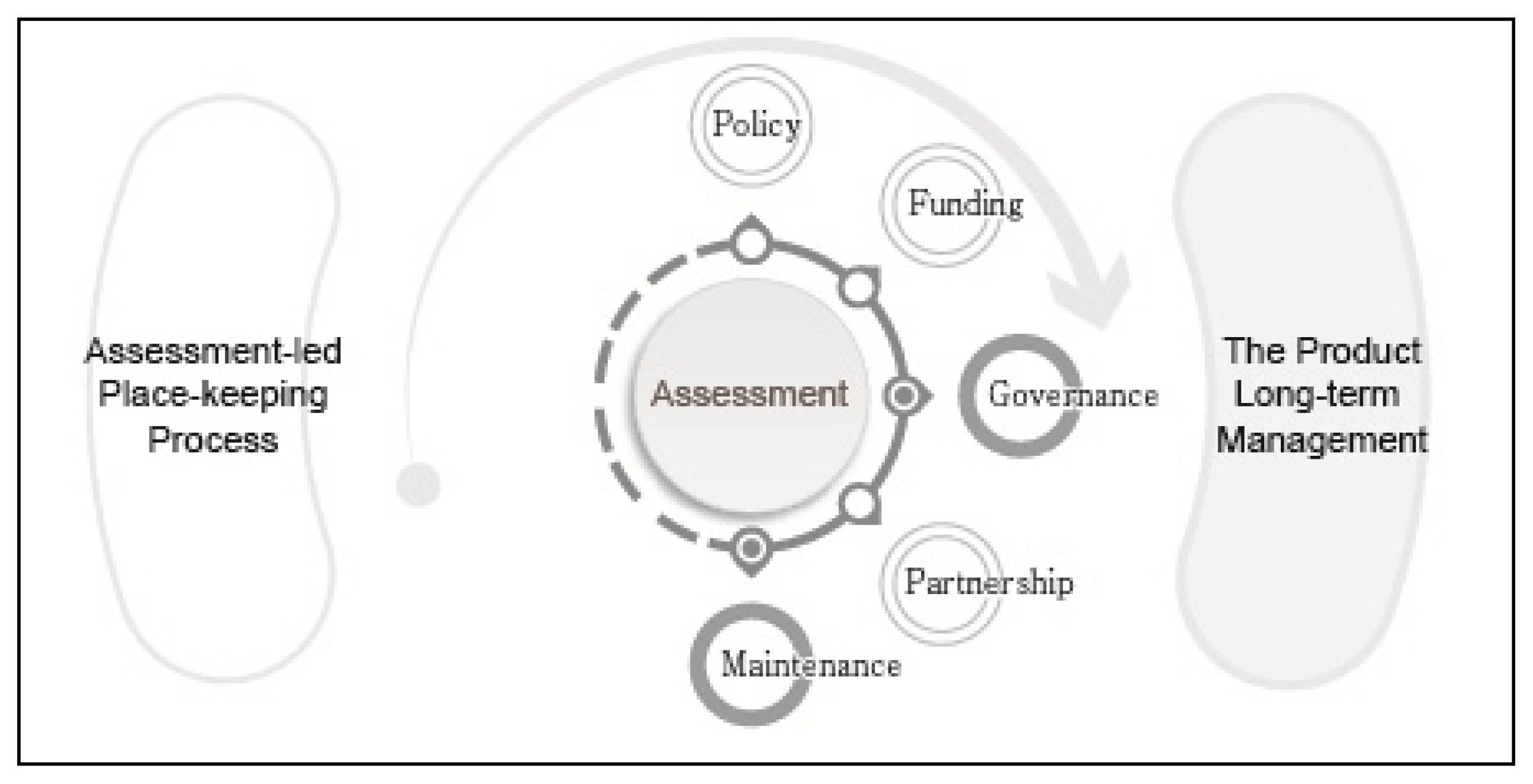

The analytical framework of ŌĆśplace-keepingŌĆÖ coined by Wild et al. (Wild et al., 2008) contextualises the importance of long-term management, which brings positive social, economic, and environmental benefits to people and nature for future generations (Dempsey et al., 2016). Place-keeping analytical frameworks, in general, explore how to enhance and maintain the qualities of and benefits derived from public spaces, including green spaces maintained through long-term management, while employing the dimensions of policy, funding, governance, partnership, maintenance, and evaluation. Application of the place-keeping analysis framework detailed in Table 2 can be used to support and evaluate practical and actual connections between the quality of space management and the feasibility of long-term management.

The framework not only provides comprehensive and meaningful approaches on how to properly manage such spaces by defining resources and allocative structures, norms, and ideas for each dimension of the place-keeping analysis, but also helps to derive evaluation indices. The availability and reliability of this framework has recently broadened the evaluation of various spaces, particularly in terms of the management of these spaces, and has also extended these opportunities to other countries. These evaluations have included an analysis of citizens managing urban green spaces in 21 European countries (Mattijsse et al., 2017), revealing an interconnection between quality of life and green space management (Nam and Dempsey, 2019b), case studies of community-led particulate alleviation gardening (Nam and Kim, 2019b) in the UK, a managerŌĆÖs perspective on place-keeping for public green spaces management in Norway and Sweden (Fongar et al., 2019), and island landscape management in Korea (Nam and Oh, 2020).

Place-keeping analytical frameworks provide reliable approaches to long-term management. However, the approaches should be monitored, insofar as each dimension is well-operated. Therefore, the norms for evaluation can be prioritised in the context of the proper and long-term management of these spaces. In addition, evaluations can help reflect a wide range of recent drivers of changes in green space management. This research, therefore, employed an assessment-focused, place-keeping analytical framework of emerging issues related to green space assessments, while acknowledging that assessment-focused, place-keeping analytical frameworks have been applied to understand the contribution of green space assessment tools in their long-term management.

Green spaces are well-recognised as harnessing positive benefits for humanŌĆÖs quality of life, including their overall health and well-being (Nam and Dempsey, 2019b). In this study, many of the benefits can be derived by well- or properly managed green spaces. In some cases, green spaces can provide mental and physical health benefits to people (Nam and Kim, 2021). Boosting users to improve their walkability and recreational experiences, and to enjoy a natural and green environment can play a role in various approaches to addressing ill-health and obesity (CABE Space, 2003), reducing physical and mental health disparities (Mitchell et al., 2015), and contributing to enhanced well-being (CABE Space, 2009).

With respect to the environment, well-managed green spaces can play a significant role in developing urban climate resilience, decreasing urban heat in the summer, and reducing urban flooding (National Trust, 2014). In terms of the economy, CABE Space (2003) noted that properly managed green spaces can provide such stakeholders, e.g., householders, customers, and services providers, with positive and financial benefits that influence the value of near-by domestic properties. Well-managed green spaces also play a crucial role in contributing to the level of environmental and economic awareness of villages, districts, and cities (CABE Space, 2009). This can involve providing opportunities for more frequent exercise and increased accessibility to green spaces and nature, reducing expenses by leveraging public services without fees, and contributing to childrenŌĆÖs education (CABE Space, 2009).

CABE Space (2004) has also concluded that in terms of social context, the benefits of well-kept and maintained public green spaces involve making users feel safe from unwanted occurrences, such as antisocial behaviour and vandalism. In other cases, well-managed landscapes are associated with peopleŌĆÖs perceptions and actions. The process of enhancing green spaces to become better places can deliver positive impacts on usersŌĆÖ perspectives which, in turn, can positively influence a personŌĆÖs mental and physical well-being and health (Landscape Institute, 2013). From a practical point of view, well-maintained or managed green spaces can convey cleanliness, where the term ŌĆśwell-maintainedŌĆÖ is often associated with a sense of quality of the spaces, as well as the maintenance activities that are used to maintain the space (Dempsey and Burton, 2012).

Effective space management, which is evaluated as proper green spaces maintenance, is pragmatic and holistic in nature, meaning that this process focuses on ŌĆśdoingŌĆÖ, which encompasses intellectual actions such as designing and planning (Hitchmough, 1994, p. 2). This concept coincides with the understanding that well-managed spaces, including green spaces, can be systematically managed in the long term (Randrup and Persson, 2009).

While these benefits could generally be limited to such landscapes, e.g., well-managed green spaces, it should also be noted that derelict, unmanaged, or poorly managed open/green spaces can create or exacerbate unwanted happenings, such as anti-social behaviour (e.g., graffiti, flying tipping, and vandalism; European Commission, 2010). Wilson and KellingŌĆÖs ŌĆśBroken Window TheoryŌĆÖ is a well-known academic theory (Wilson and Kelling, 1982) that uses broken windows as a metaphor to explain disorder within neighbourhoods; it can also be used to explain these negative influences while emphasising the necessity for regular or proper management. Poorly managed green spaces in towns and cities are likely to see declines in overall use and positive experiences. This might have negative effects on peopleŌĆÖs social experiences, health, well-being, and quality of life (Newton, 2007). In some instances, derelict, insufficient, or abandoned management can lead to more serious anti-social and criminal behaviours (Wilson and Kelling, 1982), as well as to a tremendous loss of security, safety, and standardised green spaces (Burton et al., 2014; Perkins, 2010).

It is clearly accepted that there is remarkable evidence to support the arguments and claims that well-managed green spaces are more likely to harness positive associations with peopleŌĆÖs well-being, while insufficiently or poorly managed, or unmanaged, landscapes/green spaces are more likely to have negative effects. Further, the key to addressing these negative impacts and long-lasting positive impacts could lead to an understanding of how well-managed green spaces can be sustained in the long term.

The GFA was first established in 1996, with the first actual award being given in the following year. The core aims of the GFA are to enhance the standard/quality of parks and green spaces, and to enhance public green spaces and parks, which might be responding to the high expectations of local residents, users, and green space-related stakeholders (Greenhalgh et al., 2006). The GFA has been implemented since 1996, and has been underpinned by a scoring-based assessment of the GFA, leading to the creation of awards for high-scoring public spaces and parks (DETR, 1999).

According to the DETR policy, the importance of the GFA implied that urban green spaces and parks are necessary. Some parks and green spaces won by GFA can be reckoned as proven quality and standards. In turn, the GFA is reliable and represents EnglandŌĆÖs first national green space assessment tool approved by the UK Government Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), but it was actually licensed in 2012 by Keep Britain Tidy - an independent charity established in 1955 that aimed to improve places (Nam and Kim, 2019a). The GFA is not a permanent assessment tool, meaning that authorised process for another five years was conducted as a national green space evaluation index in 2015 (Nam and Kim, 2019a). According to a government report published in 2006, the GFA was recommended for use as a national standard for the development of urban green space management (The National Audit Office, 2006). More importantly, the emphasis and influences on the GFA, along with the pursuit of improving green space standards at a national level, was cascaded to local areas. In the area of local government, Sheffield, the fourth biggest city in the UK, has also bench-marked the GFA when launching their own simplified and independent green space assessment in various areas in the city. The Sheffield City CouncilŌĆÖs green space assessment audit tool, which is called the ŌĆśSheffield StandardŌĆÖ, is a representative example that uses GFA-focused green assessment criteria developed for local areas. This may reflect the emerging paradigm that promulgates the significance of green space management.

The GFA aims to provide enhanced accessibility to standard green spaces, emphasising users (including potential users) and placeness based on sufficient green space management and criteria (Table 3)(Greenhalgh and Parsons, 2004). The GFA has a tendency to mirror approaches of recent policy contexts to green space management through a wide range of criteria and their necessary to evaluate the implementation of policies (Dizdaroglu, 2017).

In much of the literature, the GFA places an emphasis on investigating green space standards. Such green space audit tools can handle a variety of domains (e.g., general conditions such as vegetation, cleanliness, facilities, and equipment; Bedimo-Rung et al., 2006; Broomhall et al., 2004; Cavnar et al., 2004; Edwards et al., 2013; Foster et al., 2006; Gidlow et al., 2012), ecological and natural diversity; and plantings (M├╝ller and Kamada, 2011). The GFA is widely considered to use integrated approaches when monitoring environmental, ecological, marketing, and regular maintenance, as well as overall management. This approach was well-benchmarked, for example, in the Nordic Green Space Award (NGSA) (Lindholst et al., 2016), which was used in an integrated way in four Nordic countries; this was adapted from GFA-based criteria with some revisions and variations.

Understanding the value of GFA is based on reflecting contemporary drivers of change in the context of green spaces. For instance, community involvement-focused governance approaches, including the opportunity to engage in decision-making processes, represents a core key to managing and developing green spaces in the UK and worldwide. The GFA involves assessing community engagement and empowerment, or their associated activities, as detailed in the study by Mattijssen et al. (2018). In other similar contexts, this paradigm has been illustrated, such as in the case of the TAES (CABE Space, 2007) and the International Awards for Liveable Communities (LivcomAward, 2013), which monitor community-centred activities (but do not have stronger applications than the GFA), noting that an awareness of active community involvement and activities in the process of assessing green spaces might contribute to growing understandings of the importance of green space management.

However, from a different perspective, the GFA has its weaknesses, as trained or qualified experts can be involved in the assessment processes both at the desk and in the field. Therefore, there are arguments that user perspectives and experiences in green spaces have been well-reflected. This is because there has been increasing consideration of usersŌĆÖ perceptions toward current issues that can be associated with green space standards. According to DŌĆÖAntonio et al. (2013), users in green spaces and parks should serve as judges in the decision-making process, as this can prevent the degradation of green spaces. Additionally, with respect to policy, opportunity for and reflection of decision-making should be framed in green space assessments. This can help understand usersŌĆÖ needs for quality of park and green spaces.

Further, the GFA did not take into account funding issues in contemporary financial crises and partnerships, which have been underlined as key factors of place-making and keeping, even though UK policy has often mentioned them recently. The GFA can be widely utilized to develop and understand standards of current green space maintenance, which is a key point; however, it is limited in its ability to integrate and assess extended green space management in relation to policy, funding, and partnerships. Thus, the approach toward the GFA will have to pursue an integrated structure coordinating the dimensions, which can lead to long-term management.

The categorization and analysis of the domains collected from 18 assessment tools in the UK, Europe, USA, and Australia since 1996, as based on the 8 domains of the GFA, revealed the following four findings: the persistence of conventional maintenance and its importance, the emphasis on accessibility by expanding practical boundaries, the inevitability of raising community involvement, and the diversity of involvement in the judging process (Table 4).

The conventional and fundamental maintenance (e.g., cleanliness and facility maintenance) in green space management still dominates the various domains of park and green space assessment tools. The importance of this has remained an essential factor, as it cannot be overlooked in terms of user satisfaction. However, the evaluation items showed greater specificity in the ŌĆśsettingŌĆÖ domain. In the case of plant materials in green spaces, which represent the most important factor in parks, they tend to be specified in the ŌĆśmanagementŌĆÖ assessment domain. For example, it is evaluated that the maintenance of perennial and annual plants is performed separately. In the case of facilities, it has been shown that facility maintenance assessments for general use and recreation facilities should be conducted separately. As such, it is noted that domains to assess maintenance are continuously persist ed as the cornerstones of assessment.

The emphasis on the accessibility of green spaces through the expansion of practical boundaries is also seen during assessments. Essentially, the areas within and beyond the green spaces can be expanded and managed. These are evaluated based on the overall convenience and accessibility of green spaces. Maintenance of the external environment is also required by the assessment domains, so as to invite more users. In addition, the maintenance assessment of signs with location information of green spaces and bulletin boards containing information related to various park uses reflects this. This seems to broaden the actual boundary of green spaces by expanding the maintenance framework, which tends to be focused on the inside of existing green spaces; it can also lead to an expansion of the functions and roles of green spaces.

Community participation and expansion of community membersŌĆÖ roles in increasing community involvement have been leading trends since the mid-2000s. Although this has been reflected in some green space assessment since the late 1990s, the actual expansion in Europe, the United States, and Australia became evident in the mid-2000s. Interestingly, community involvement is different from the previous social perceptions, where community participation is reckoned through voluntary participation. However, considering the expansion of the green space assessment domains, community participation has now become an essential factor. In other words, it has been shown that community participation accounts for a large proportion of contributions in green space maintenance (Nam and Dempsey, 2019). This highlights that the issue of governance is also reflected in green space assessment.

Increasing participation of various judges in green space assessments represents an interesting finding in this study. In the late 1990s, the assessment process consisted of pre-trained judges. However, since the mid-2000s, the participation of experts, focus group participants, users, and local residents has been noticeably encouraged. In other words, various stakeholders are now involved in the assessment process. This change reflects the perceptions that users and potential users are involved in the assessment.

The data analysis conducted via the assessment-based, place-keeping analytical framework and its five dimensions considers three dominant themes: qualitative improvement of green spaces, quality of life, and budget cuts, which can affect the importance of assessment in the context of green space management. This calls for a coordinated understanding of the five dimensions of this framework in the assessment, where the assessment-based place-keeping analytical framework explores the concept of ŌĆślong-term managementŌĆÖ, which involves the positive impacts of green spaces on peopleŌĆÖs quality of life (Fig. 2).

Sustainable and continual assessment-based approaches to properly maintaining green spaces, along with policy support, have been the keys to framing long-term management. Neoliberalism and competitive composition sparked by the economic crisis in the UK showed negative effects on green space quality. This brought about a holistic, policy-based assessment. For instance, the Department of the Environment, Transport, the RegionsŌĆÖ Urban White Paper of 2000, and the Urban Parks ForumŌĆÖs Public Parks Assessment from 2001, followed by the PPG17 from the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM), emphasized the importance of green space quality to harness its positive benefits. This increased emphasis calls for a systematic assessment approach, which reflects a wide range of current issues. The UK GovernmentŌĆÖs Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) has employed GFA as national green space assessment tool since 2012. As mentioned in the previous chapter, GFA has contributed to better green spaces framed in a reflection of continuous policy. This shows that assessment-focused policy systemization and overall continuity contribute to the proper maintenance of green spaces by identifying their status and reckoning the need for a continuous management system. Therefore, in the TAES Framework (CABE Space, 2007), there is a need to add the assessment domain to improve our understanding of green space-related policies.

A newly emerging challenge to green space management in an era of austerity is the need for self-generating income. The assessment item does verify income generation approaches (e.g., marketing category in the GFA). This means that the dynamics between assessment and income generation are interrelated, as enough funding can lead to the deployment of resources that can enhance the condition of green spaces. In terms of the introduction of neoliberalism and compulsory competitive tendering derived by the economic recession, this paradigm has been permeated throughout the context of green space management. Therefore, new changes require the ability to identify opportunities for income generation. This could ultimately ensure that green spaces are practically managed in the long term.

Reliance on community involvement accounted for a considerable portion of green space management. This was due to the lack of resources, including finance and labour, to manage green spaces. Dramatic budget cuts for green space management and the overall deteriorating quality of these spaces have led to increased community engagement and decision-making authority. Therefore, the assessments showed the impacts of governance on the surviving green spaces after monitoring how much the community became involved in the maintenance and management of these spaces, while encouraging them to become more actively involved. This is reflected in the categories featured on most of the assessment tools identified in this study, where categories for assessing community involvement and activities are key. This illustrates that governance relies on community involvement, and assessment of community engagement is inevitable in the long-term management of green spaces that face budgetary deficits.

The term ŌĆśpartnershipŌĆÖ connotes sharing responsibility for green space management and societal corporatism. Thus, such assessment tools (e.g., The TAES Framework 2007) contain the domain to monitor partnership working. This process should be expanded upon due to the vague partnership approaches used, meaning that concrete and detailed structures and processes for partnerships are not clearly established. It is noted that growing concerns associated with monitoring partnerships across detailed domains can provide the structure needed for partnerships in green space management. This will also lead to stakeholdersŌĆÖ varying involvement, responsibility sharing, and effective partnership functions.

On-site maintenance is still centred on activities in green space management because users often or regularly visit and express their satisfaction on the condition of green spaces. The direction of assessment also includes various factors associated with maintenance, ranging from planting to heritage facilities. However, anti-social behaviour and vandalism caused by poor maintenance are arising as issues since these activities are directly linked to the health, safety, and frequency of visits to green spaces. As mentioned in the previous chapter, in order to address these negative issues, recent assessment domains have expanded to include intangible boundaries, encompassing the areas both inside and outside green spaces, where the focus is on security, health, and safety. Thus, the scope of green space management can be inevitably broadened. Nevertheless, clearly addressing these issues will bring about an increase in positive benefits from properly and long-managed green spaces, while ensuring that the appropriateness of green spaces is made known.

By assessing and understanding the negative factors associated with poorly managed green spaces, it may be possible to address these while reflecting the recent trends that have emerged in green space management. In this study, green space management is essentially required over the long term. This finding is derived through an analysis of well-managed green spaces and the GFA. However, it was also found that policies, budgets, governance, partnerships, maintenance, and evaluation should be applied simultaneously. Recent green space assessments have highlighted the importance of governance based on community involvement and regular maintenance. However, monitoring policies and partnerships have been overlooked. Accordingly, future drivers of change in green space assessments must shift toward an expanded and coordinated structure that coordinates policies, budgets, governance, partnerships, and maintenance. However, the GFA has several priorities: firstly, the GFA needs to establish additional domains that reflect current policy and funding issues because they represent one of the keys to supporting the overall long-term management of green spaces. Secondly, the domains that promote governance-related activities - in particular, how to invite communities - need to be added because the contributions of community involvement were demonstrated and underlined. Thirdly, when it comes to the judging process, increasing numbers and varying types of stakeholders need to be invited as judges of the perceived quality of green space management. Combined, these changes will ultimately lead to the positive benefits that can emerge from well-managed green spaces in the long term.

Fig.┬Ā1

The study approach underlined by the PSALSAR framework.

Source: modified from Mengist et al. (2020)

Fig.┬Ā2

The process of the assessment-led, place-keeping analytical framework and the product for long-term management.

* Governance and maintenance: Already properly met Policy, funding, and partnership: Essentially will be developed

Table┬Ā1

Collected green space assessment tools

Table┬Ā2

An analytical framework for the dimensions of place-keeping

Resources: revised table derived from Dempsey et al. (2014).

Table┬Ā3

Criteria and sub-criteria for the Green Flag Award

Table┬Ā4

Analysis of characteristics of green space assessment domains

| Codes | WP | HSS | WMC | EM | BLH | CI | MC | MG | Judges* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSA-1 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | Tr |

| GSA-2 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Tr |

| GSA-3 | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Tr |

| GSA-4 | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Tr |

| GSA-5 | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Fg |

| GSA-6 | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Fg, Us |

| GSA-7 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Ex, Us |

| GSA-8 | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Ex, Us |

| GSA-9 | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | La |

| GSA-10 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | Ex |

| GSA-11 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Lr, Us |

| GSA-12 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Lr |

| GSA-13 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | Lr |

| GSA-14 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Sth |

| GSA-15 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Fg |

| GSA-16 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÜ | Sth |

| GSA-17 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | ŌłÆ | Lr, Tr |

| GSA-18 | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | ŌłÜ | Sth |

References

Burton, M, N Dempsey, A Mathers. 2014. Connecting making and keeping: Design and management in place-keeping. Place-Keeping: Open Space Management in Practice. 125-150.

Broomhall, M, B Giles-Corti, A Lange. 2004. Quality of Public Open Space Tool (POST) Perth, Western Australia: School of Population Health, The University of Western Australia.

Bedimo-Rung, A, J Gustat, BJ Tompkins, J Rice, J Thomson. 2006. Development of a direct observation instrument to measure environmental characteristics of parks for physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 3(Suppl 1):176-S189.

Cavnar, MM, KA Kirtland, MH Evans, DK Wilson, JE Williams, GM Mixon. 2004. Evaluating the Quality of Recreation Facilities: Development of an assessment tool. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration. 22(1):96-114.

CABE Space. 2003. The value of public space, how high quality parks and public spaces create economic, social and environmental value London, UK: Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment.

CABE Space. 2007. Parks and open spaces: Towards an excellent service London, UK: Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment.

CABE Space. 2009. Open Space Strategies: Best Practice Guidance London, UK: Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment.

Coral, C, W Bokelmann. 2017. The role of analytical frameworks for systemic research design, explained in the analysis of drivers and dynamics of historic land-use changes. Systems. 5(1):20.

https://doi.org/10.3390/systems5010020

Dempsey, N, M Burton. 2012. Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 11(1):11-20.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2011.09.005

Department for the Environment. Transport and the Regions (DETR). 1999. Towns and country parks London, UK: The Stationary Office.

Dizdaroglu, D 2017. The Role of Indicator-Based Sustainability Assessment in Policy and the Decision-Making Process: A Review and Outlook. Sustainability. 7(9):1018.

Dempsey, N, M Burton, R Duncan. 2016. Evaluating the effectiveness of a cross-sector partnership for green space management: The case of Southey Owlerton, Sheffield, UK. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 2016(15):155-164.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.12.002

DŌĆÖAntonio, F, C Iacovella, A Bhide. 2013. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 42(5):509-517.

https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13194

Dempsey, N, H Smith, M Burton. 2014. Place-Keeping: Open Space Management in Practice (pp. 274London, UK: Routledge.

Edwards, B, M Gray, B Hunter. 2015. The impact of drought on mental health in rural and regional Australia. Social Indicators Research. 121:177-194.

European Commission. 2010. Making our cities attractive and sustainable: How the EU contributes to improving the urban environment European Commission.

Ellicott, K 2016. Raising the standard Department of Communities and Local Government. London:

Foster, C, M Hillsdon, A Jones, J Panter. 2006. Assessing the relationship between the quality of the urban green space and physical activity London: CABE.

Fongara, C, TB Randrupb, B Wistr├Čmb, I Solfjeld. 2019. Public urban green space management in Norwegian municipalities: A managersŌĆÖ perspective on place-keeping. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 44:2019. 126438.

Grant, MJ, A Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal. 26(2):91-108.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Grahn, P, UK Stigsdotter. 2010. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landscape and Urban Planning. 94(3ŌĆō4):264-275.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.10.012

Gidlow, CJ, NJ Ellis, S Bostock. 2012. Development of the neighbourhood green space tool (NGST). Landscape and Urban Planning. 106:347-358.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.04.007

Greenhalgh, L, J Newton, A Parsons. 2006. Raising the standard-The Green Flag Award Guidance Manual London, UK: CABE Space.

Hitchmough, JD 1994. Urban Landscape Management (pp. 2Sydney, Australia: Inkata Press.

Picavet, HSJ, I Milder, H Kruize, S de Vries, T Hermans, W Wendel-Vos. 2016. Greener living environment healthier people?: exploring green space, physical activity and health in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Preventive Medicine. 89:7-14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.021

Kaplan, S 2001. Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior. 33(2001):480-506.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973106

Landscape Institute. 2013. Public Health and Landscape London, UK: Landscape Institute.

Lindholst, AC, C Cecil, K van den Bosch, CP Kjoller, S Sullivan, A Kristoffersson, H Fors, K Nilsson. 2016. Urban green space qualities reframed toward a public value management paradigm: The case of the nordic green space award. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 17(2016):166-176.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.04.007

LivCom Awards. 2011 The international awards for liveable communities Available at http://www.livcomawards.com

. Accessed 30 December 2021

Mengist, W, S Teshome, G Legese. 2020. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX. 7(2020):100777.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2019.100777

Mitchell, RJ, EA Richardson, NK Shortt, JR Pearce. 2015. Neighbourhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental Well-Being. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 49(1):80-84.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.017

M├╝ller, N, M Kamada. 2011. URBIO: an introduction to the International Network in Urban Biodiversity and Design. Landscape and Ecological Engineering. 7(1):1-8.

Miller, RW 1997. Urban Forestry, Planning and Managing Urban Green spaces (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. New Jersey, USA:

Mattijssen, T, A Buijs, B Elands, B Arts. 2018. The ŌĆśgreenŌĆÖ and ŌĆśselfŌĆÖ in green self-governance - a study of 264 green space initiatives by citizens. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning. 20(1):96-113.

Mattijssena, T, APN van der Jagt, AE Buijs, BHM Elands, S Erlwein, R Lafortezz. 2017. The long-term prospects of citizens managing urban green space: From place making to place-keeping? Urban Forestry and Urban Greening. 26(2017):78-84.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.05.015

National Trust. 2014. DCMS English Heritage New Model Consultation Swindon, UK: National Trust.

Newton, J 2007. Wellbeing and the Natural Environment: A brief overview of the evidence Bath, UK: The University of Bath.

Nordic Green Space Award. 2011. Nordic Green Space Award Oslo, Norway:

National Audit Offce. 2006. Enhancing Urban Green Spaces London, UK: National Audit Office.

Nam, J, N Kim. 2019a. An understanding of green space policies and evaluation tools in the UK: A focus on the green flag award. Journal of the Korea Society of Environmental Restoration Technology. 22(1):13-31.

https://doi.org/10.13087/kosert.2019.22.1.13

Nam, J, K Kim. 2019b. Exploring community-led particulate matters abatement-The cases of particulate matters abatement community gardens in London, UK. Journal of Recreation and Landscape. 13(3):39-52.

https://doi.org/10.51549/JORAL.2020.13.3.039

Nam, J, K Kim. 2021. Determining correlation between experiences of a sensory courtyard and DAS (Depression, Anxiety and Stress). Journal of People Plants Environment. 24(4):403-413.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2021.24.4.403

Nam, J, N Dempsey. 2019a. Place-keeping for health? Charting the challenges for urban park management in practice. Sustainability. 11(16):4383.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164383

Nam, J, N Dempsey. 2019b. Understanding stakeholder perceptions of acceptability and feasibility of formal and informal planting in SheffieldŌĆÖs district parks. Sustainability. 2019(11):360.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020360

Nam, J, N Kim, D Kim. 2019. Exploring policy contexts and sustainable management structure for park regeneration. Journal of the Korea Society of Environmental Restoration Technology. 22(4):15-34.

https://doi.org/10.13087/kosert.2019.22.4.15

Nam, J, C Oh. 2020. Delivering the implication of place-keeping on long-term island landscape management. The Journal of Korean Island. 33(1):247-265.

Perkins, HA 2010. Green spaces of self-interest within shared urban governance. Geography Compass. 4(2010):255-268.

Pugh, TAM, AR MacKenzie, JD Whyatt, CN Hewitt. 2012. Effectiveness of green infrastructure for improvement of air quality in urban street canyons. Environmental Science Technology. 46(2012):7692-7699.

https://doi.org/10.1021/es300826w

Randrup, T, B Persson. 2009. Public green spaces in the Nordic countries: development of a new strategic management regime. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 8(1):31-40.

Richardson, EA, J Pearce, R Mitchell, S Kingham. 2013. Role of physical activity in the relationship between urban green space and health. Public Health. 127(4):318-324.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2013.01.004

Sandstr├Čm, U, P Angelstam, G Mikusi┼äski. 2006. Ecological diversity of birds in relation to the structure of urban green space. Landscape and Urban Planning. 77(1ŌĆō2):39-53.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.01.004

Sheffield City Council. 2013. Sheffield Standard Sheffield City Council. Sheffield, UK:

The National Audit Office. 2006. Enhancing urban green space The National Audit Office. London:

Townsend-Small, A, CI Czimczik. 2010. Carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions in urban turf. Geophysical Research Letters. 37:L02707.

https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041675

Wild, TC, S Ogden, DN Lerner. 2018;An innovative partnership response to the management of urban river corridors-SheffieldŌĆÖs river stewardship company. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Urban Drainage; IAHR/IWA, Edinburgh, UK. 23 September 2018.

Wilson, JQ, GL Kelling. 1982. Police and neighborhood safety. Broken windows. Atlantic Monthly. 127(1982):29-38.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 1,000 View

- 15 Download

- Related articles in J. People Plants Environ.