|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 23(1); 2020 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

This study focused on the composition of the exterior space of Parkjinsagoga, the types of gardens and planting and the landscape characteristics of walls, and examined its meaning as modern garden remains. Parkjinsagoga is a modern Korean house that harmonizes traditionality and practicality, and is an invaluable material for research not only on architecture but also on changes in the gardens of upper-class gardens. Its exterior space can be divided largely into An-chae (inner house), Outer Sarang-chae (outer house) and Inner Sarang-chae areas, and a garden was created in each yard (inner garden). In particular, one thing noticeable is that the yard of Inner Sarang-chae, unlike traditional gardening styles, was actively decorated. At the center of the yard of Inner Sarang-chae, two atypical planters and artificial moundings were created and the traffic line of the garden was designed to enjoy them while walking. An atypical pond was created on one of the artificial moundings and trees and shrubs were densely planted. Natural stones were also placed. The style seemed to be affected by Japanese gardens. These characteristics observed in the gardens of Parkjinsagoga are closely related to the transitional characteristics that traditional gardens started to show in modern times. A total of 35 families and 57 species were planted in the gardens of Parkjinsagoga and there were 19 species of tall trees, 20 species of shrubs and 17 species of flowering plants. The number of species planted in the garden of Inner Sarang-chae was the highest, and a total of 22 species of tall trees and shrubs. The walls in Parkjinsagoga were basically earth and rock-fill walls but their materials and patterns differed depending on the type of spaces. Four types of walls were found to be introduced to the house.

Parkjinsagoga is an old house of Park’s family built in the late Joseon period in Cheonggwang-ri, Gaecheon-myeon, Goseong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do. The house was designated as Gyeongsangnam-do’s Cultural Property Material No. 292 on February 22, 2001, and was known to produce many devoted sons and jinsas (those who passed the first examination for office) from generation to generation. Devoted son, Hyo-Geun Park (1800–1853) was born in this house and his son Han-Hoe Park and his grandsons served jinsas in a row. For this reason, this house is called Parkjinsagoga. The house was extended and repaired in the Japanese colonial period and this modern Korean house well harmonizes practicality and traditionality, being recognized as an invaluable material for research on the architecture of the late Joseon period. In addition, its gardens that were created in the same period has been well preserved until now, which improves its landscape values. In particular, although the garden of Sarang-chae (a men’s quarter) is an invaluable case that shows the styles of gardens created in upper-class houses in the transitional period called the Japanese colonial period, it has not been academically researched. Detailed information on the history of the gardens were collected from the eldest son of the family who has managed the house. However, if the gardens are no longer researched as they are, it will be more difficult to ascertain the original form and history of the gardens through historical research in the future. Against this backdrop, this study conducted on-site investigations and interviews to analyze the status and landscape characteristics of the exterior space of Parkjinsagoga that has not been academically researched until now. The results will be left as one of the important cases of the gardens created in upper-class houses in the Japanese colonial period and will serve as a clue that shows one aspect of the gardening styles back then. The purposes of this study were to analyze the landscape characteristics of the gardens created in Parkjinsagoga focusing on its exterior space, the types of gardens and planting, and the landscape characteristics of walls and thus to examine the meaning and characteristics of the gardens as modern garden remains.

Jang (2004) was the only study that examined Parkjinsagoga examining one of the target sites in discussing the architecture of modern Korean houses built in the central area of Gyeongnam. The study, however, focused only on its architectural characteristics, and there has been no in-depth study on its exterior space.

There are some studies that comprehensively researched the gardens created in Korea in modern times when the gardens of Parkjinsagoga were created. Kim (2015) analyzed the styles and components of gardens, facilities and planting characteristics targeting Japanese-style gardens created in Korea in the 1920s–30s, and reported that they were mostly distributed in Jeolla-do and Gyeongsamnam-do. Lee and Kim (2006) selected 14 gardens created between the mid-19th century and the mid-20th century and analyzed the styles of building gardens, locations, spatial construction and design elements and discussed the transitional aspects of traditional gardens. The study reported that the space of gardens changed centering on Sarang yard and that other changes were observed such as changes in the form of gardens and mixed styles, changes in the function of Sarang yard and inner-directed visual structures centering on gardens. Lee and Rho (2013) examined gardens created in modern times individually and selected Seogo-jeongsa and Sameun-jeong in Miryang to identify transitional characteristics such as the characteristics of separate houses created in the late Joseon period and the emergence of foreign tree species. In addition, Kim (2009) and Kim et al. (2011) examined the typical characteristics of Japanese-style gardens created in Korea during the Japanese colonial period. Meanwhile, Park (2011) selected 47 upper-class houses built in the Joseon period and analyzed their gardening styles and the process of modern division observed in the gardens of traditional houses. This study aimed to confirm that the gardens of traditional houses change depending on the active expression of garden types in Sarang yard, the expanding area of gardens and pursuit of decorativeness and practicality.

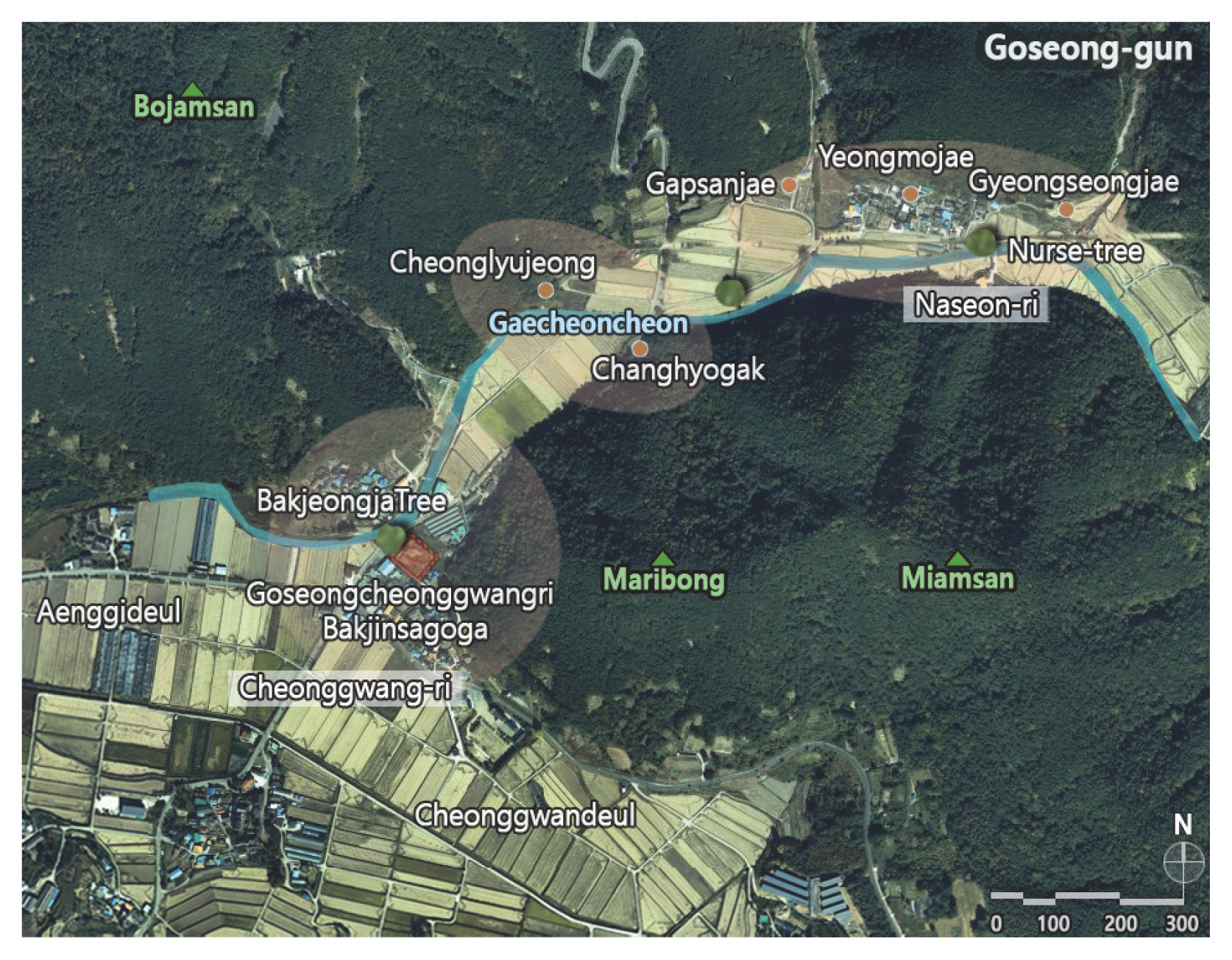

The administrative location of Parkjinsagoga is 292–3, Cheonggwang-ri, Gaecheon-myeon, Goseong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do. The head house of the Miryang Park Chungheongong Clan was a modern traditional Korean house to which the family moved from a village in Naseon-ri near the current place where the family first settled. Several historical sites of the Miryang Park family such as houses, studies and monument houses (Parkjinsagoga, Yeongmojae, Gyeongseongjae, Cheongryujeong, Changhyogak, etc.) are distributed across the village (Fig. 1). These historic sites in the village were targeted in this study to understand their historic and cultural context such as the process of forming a village and their relations with Parkjinsagoga.

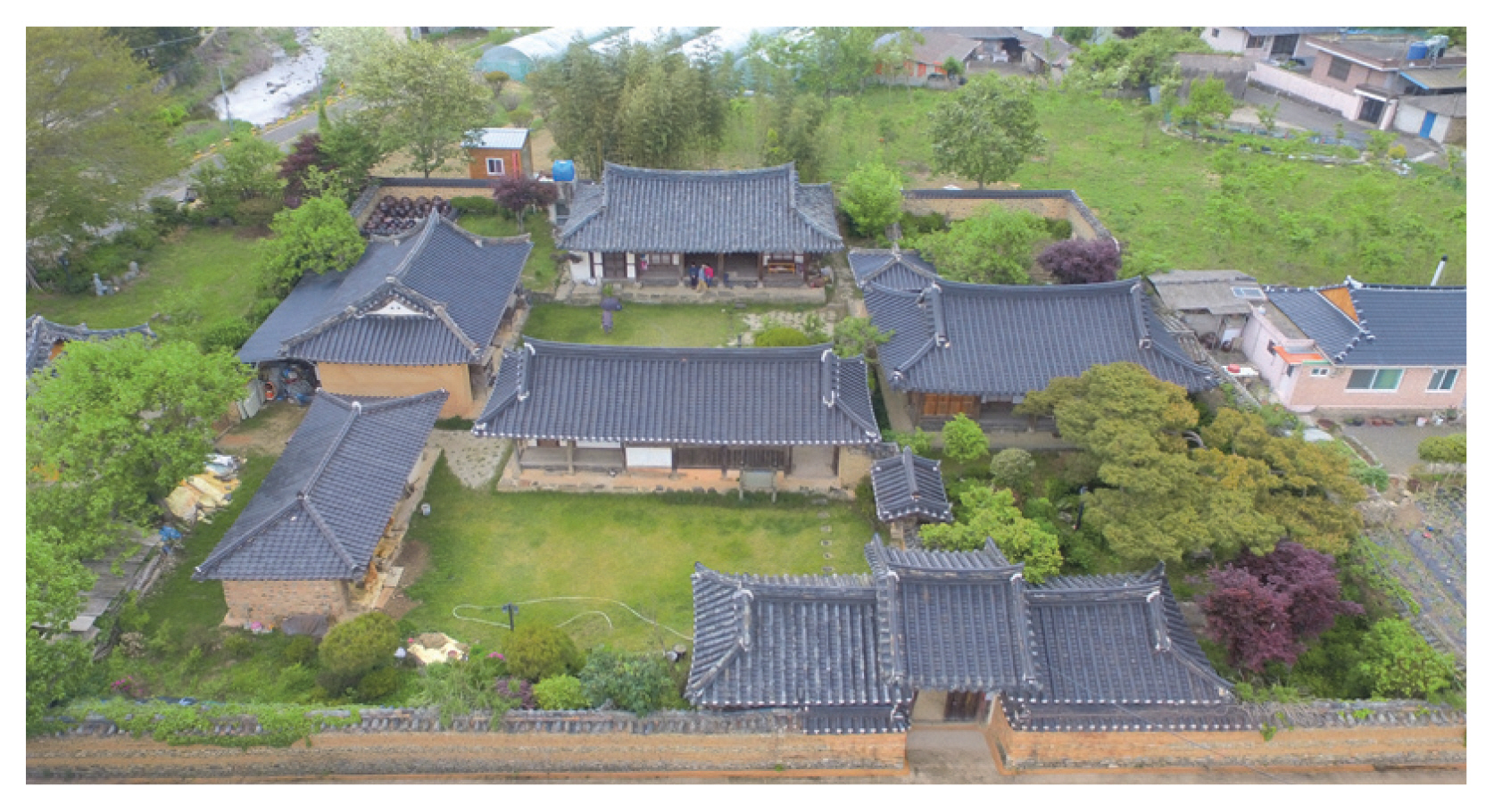

Parkjinsagoga, the main research target, is composed of seven buildings and each building has a yard (inner garden). Among them, this study focused on the garden of Inner Sarang-chae of which original form has been well maintained since it was created in the early 20th century and examined the elements of its exterior space such as yard and wall. The temporal scope of this study was set from the creation of the village in the early Joseon period to now, but mainly focused on changes in the landscape of the garden from the early 1900s when the garden was created to now.

Since Parkjinsagoga has been maintained well and structures, gardens and facilities remained in a good condition, it is important to examine their status. An on-site investigation was conducted three times in March, May and August, 2018 and physical environments, landscape elements and trends in changes were surveyed and analyzed. The results were used as base information in this study. The elements of the exterior space such as structures, gardens, walls and facilities were measured and mapped using the AutoCAD program. In addition, the species of plants in each garden were surveyed and listed, and the status of distributed plants was mapped.

In-depth analysis was conducted based on the surveyed data through literature review and interviews. Cheonggangmungo, a compilation of 3,000 ancient documents, contains information on Parkjinsagoga, and especially Cheonggangmunjip (unpublished), a translated version of poetry and prose in the compilation was referred to mainly. The historical background of the house, such as the history of the house, historical contents related to the extension and reconstruction of the house and the creation of gardens, was heard from Mansan Sang-Ho Park, the eldest son of the Miryang Park Chungheongong Clan who was born and still lives in the village through an interview.

Electronic searches for general information and geographic information were performed using Cultural Heritage Administration (www.heritage.go.kr), Goseong-gun (www.goseong.go.kr), National Geographic Information Institute (www.ngii.go.kr), Naver, or Kakaomap.

Cheonggwang-ri where Parkjinsagoga is located is a village to which people moved and settled in the Japanese colonial period. The place to which the Miryang Park family first moved and formed a clan family in the early Joseon period is in Naseon-ri about 900 m away from the old house. Gaecheon-myeon where Cheonggwang-ri and Naseon-ri are located was originally under Jinju-gun but was incorporated into Goseong-gun in 1906. Its western side is surrounded by mountains such as Yeonghwabong (478 m) and Sirubong (541 m), part of the Yeonhwasan Provincial Park, and its northeastern side is surrounded by mountains such as Miamsan (358 m), Sogoksan (481 m) and Pildubong (418 m). On its southern side, mountains such as Namsan (425 m) and Deoksan (278 m) are located. Small streams flow through these mountainous areas and narrow valley flats are formed. Naseon-ri is a remote village in Gaecheon-myeon and is located in a narrow plain stretched near Gaecheoncheon, a stream that flows from Bosamsan in the northern direction to Miamsan in the southeastern direction. It is connected to Cheonggwang-ri along the stream. Meanwhile, since Cheongwang-ri has a relatively open field compared to other valley plains, the area of arable lands in Cheongwang-ri is bigger than those in Naseon-ri. There was Dongcheong (a community office) in Nadong Village in Naseon-ri but was demolished after Korea achieved independence (Goseong-gun). The old big tree next to the Dongcheong is aged over 700 years and is designated as a protected tree. There is an old and large shade tree in Cheonggwang-ri, showing the history of the village.

Wancheondang Deok-Son Park (1484–1568?), an early member of the village, studied together with Gwang-Jo Cho (1482–1519) in the period of Jungjong of Joseon. As he was involved in the purge of 1519 called Gimyosahwa, he stayed for a while in Sanin-myeon, Haman-gun and in Jucheon Village in Guman-myeon, Goseong-gun and finally settled in Nadong Village in Naseon-ri, Gaecheon-myeon for the purpose of reclusion in the same year. Deok-Son Park who lived in seclusion became the middle progenitor of the Nadong Park family and was no longer in government service. His descendants including Hyo-Geun Park, Han-Hoi Park and Don-Byeong Park passed the first examination for office and called jinsa from generation to generation and the house of the family started to be called Parkjinsagoga, and later moved to and settled in Cheonggwang-ri in the Japanese colonial period.

Several houses, studies and monument houses are distributed across Naseon-ri and Cheonggwang-ri and form a Confucian village landscape (Figs. 1 and 2). At the entrance of the village, Changhyogak (Gyeongsangnam-do’s Cultural Property Material No. 535), a monument is built to praise the filial behavior of Jukpogong Yeong-Hoi Park (1823–1886) in 1894. In the foot of Bojamsan on the opposite side of Changhyogak, Cheongryujeong is located and was built by Cheonggang Don-Byeong Park (1863–1951) as a study and separate house. A square-shaped pond with a round island in it is located in front of Cheongryujeong and trees such as Lagerstroemia, Pinus densiflora and Salix chaenomeloides were planted around the pond. Flower beds were created along the walls within its yard. The place was repaired and decorated by Nasan Yong-Ha Park (1887–1954), and he himself designed the garden of Sarang-chae in Parkjinsagoga, which shows his special interest in creating gardens. According to the eldest son of the family interviewed in this study, elders in the family back then enjoyed the tea ceremony, and there were tea fields near the pond and outside the wall of the pavilion. There are also Gyeongseongjae, a house of Hyo-Geun Park, and Gapsanjae and Yeongmojae, houses of the Miryang Park family within the village, and Yeongmojae located at the center of the village was the house where the Park’s family stayed before moving to Cheonggwang-ri.

Parkjinsagoga was originally built by the Jeonju Choi family on an auspicious site according to the theory of divination based on topography and the family was known to prosper and become a rich family later. However, the family’s fortune went down in the late Joseon period and the house was bought by Park’s family who had considerable financial power back then and was extended and repaired as it is today. One of the important reasons why the head house was moved from Nasan-ri to Cheonggwang-ri seemed to be related to the expansion of the family. Nasan-ri where the family first settled had a narrow land and a limited area of arable lands, while Cheonggwang-ri had broad arable lands such as Anggideul and Cheonggwangdeul (Fig. 1).

The old house is located in a plain between Bojamsan and Miamsan in the southeastern direction. It has been known that there was no particularly intended direction in determining a residential location, but the facade of An-chae(a main building of house) faces in the direction of Naknamjeongmaek, one of the mountain ranges on the Korean Peninsula. Munpilbong in a distant view in the southern direction was known to have a shape that produces many scholars. As Maribong in Miamsan, a mountain at the back of the house has a shape of tiger, a bamboo forest was created near the mountain. According to the interviewed eldest son of the family, there are Miamsan at the back of the house and Aribong (Aribangi) in front of the house, which looks like a seated tiger. Rocks on the hillside of the mountain look like the teeth of the tiger and the ridge at the end of the mountain looks like the tale of the tiger. The flat and wide rock right below the mountain peak is called Gaeuji Rock.

There is an old Zelkova serrata shade tree called Parkjeongjanamu at the entrance of the village. The tree was planted and managed by the Miryang Park family as the family moved to the village. A stream flowing next to the tree, was re-directed by Yong-Ha Park who created the garden of Sarang-chae to ensure it flows close to the old house as it is.

Parkjinsagoga is an upper-class house built in the late Joseon period, and is assumed to be first built in the 1850s. According to its construction document, Daemun-chae (a big gate house) was built in 1858 and Sarang-chae and An-chae are also assumed to be built around that time. Some areas seemed to be affected by Japanese styles and be repaired later during the Japanese colonial period. This house is an invaluable material for research as the house harmonizes traditionality and practicality (Jang, 2004). An-chae was located in the rearmost part of the house in the northeastern direction, and Gotgan-chae (a storage room) and Heotgan-chae (a barn) were located at the western side of An-chae, Inner Sarang-chae at the eastern side and Outer Sarang-chae and Hangrang-chae (servants’quarters) at the southern side. A total of seven buildings were built on a sqaure-shaped land, and based on the intentionally arranged location of buildings, gardens were divided (Figs. 3 and 4).

Within the tall gate in Daemun-chae, a memorial monument for devoted sons was hung and a room, toilet and bathroom were installed. A bathtub assumed to be produced in the Japanese colonial period was installed within the bathroom, which indicates that the upper-class house was affected by the Japanese culture. Passing through Daemun-chae, there was a side door on the right side heading to the yard of Inner Sarang-chae and the door was used by outsiders.

Outer Sarang-chae built behind Daemun-chae was also used as Jungmun-chae, a mid-gate house, and it had a quite practical floor plan. A treadmill was connected to Inner yard, an inner garden, and this shows that Inner yard was utilized as a space for working, which is one of the unique characteristics of modern Korean houses (Jang, 2004). The signboard of ‘Darogyeonggwonsil’ that was hung in the main hall was the calligraphy of Chusa Jeong-Hui Kim (1786–1856), and the calligraphy possessed by Seongpa Dong-Ju Ha (1879–1944), a calligrapher in modern times affected by Chusa’s calligraphy, was engraved on the signboard. Don-Byeong Park who constructed Cheongryujeong, a separate house, enjoyed the tea ceremony and exchanged with famous figures such as Dong-Ju Ha.

Inner Sarang-chae was located at the eastern side as a separate house and was used to greet visitors. The reason why Jungmun-chae was used like Outer Sarang-chae while Inner Sarang-chae was surrounded with tall walls shows the status of Inner Sarang-chae within the house and is also in line with the formation of splendid gardens.

In addition, large-sized Gotgan-chae and Heotgan-chae were located on the western side of the house. On the eastern side of An-chae, Gobang (a store room) was installed to store household supplies and this small-sized room properly blocked the view of the back garden of An-chae and Inner Sarang-chae.

The exterior space of Parkjinsagoga can be divided based on the purpose of the spaces into An-chae, Outer Sarang-chae and Inner Sarang-chae areas (Fig. 4). When entering the main gate, the first thing you can see is Outer Sarang yard that is open and spacious. Heotgan-chae located on the western side was used as a space for working. Its floor was covered with weathered granite to ensure water is rapidly drained and a square-shape planter was installed on the wall on the western side later.

Right behind Outer Sarang-chae, Inner yard was located. It is the most spacious and secluded exterior space in the house. The exterior space surrounding Inner yard were created for women to do household work. The space was surrounded by An-chae, Gotgan-chae and Gobang, and its size was relatively very big compared to traditional upper-class houses. However, its four sides were all surrounded by buildings, which gave a cosy feeling. Chaewon, a vegetable garden, was located in the eastern side of An-chae, and a platform for crocks on the western side gave an image as living spaces. The narrow gate heading to the vegetable garden was destroyed and the location of the platform for crocks used to be a place for storing firewood.

The flower garden created along the wall on the eastern side of Inner yard was created later and there were originally a tall wall for blocking An-chae and the platform for crocks. After the wall was destroyed by rain and typhoons, crocks that used to be next to the wall were moved to next to An-chae, and a garden was created on the place to play a role as a wall. It was known that Park Sang-ho, the eldest son, created the garden in the late 1950s. There are still the remains of the wall such as tiles and it is planned to be restored.

The back yard located between An-chae and the outer wall was narrow and long. The chimney located in the back yard was built for the purpose of decoration and it was as tall as 3.5 m. There used to be a small door heading to the bamboo forest created behind the house, but only its remains are there. Near the chimney, a small-sized flower garden was created along the wall to ensure people enjoy the garden from the main room and the opposite room through their windows.

On the eastern side of the house, the Inner Sarang-chae area was located. The area was separated by walls from other yards. The yard of Inner Sarang-chae was blocked with tall walls, and gardening facilities such as planters, artificial moundings, a pond and a well were densely installed. There was a small garden behind Inner Sarang-chae and a square-shaped planter along the wall was created. Considering the characteristics of Inner Sarang-chae, a house with several wings, it was designed to ensure people enjoy a garden from the back room from which people cannot see the main garden.

Traditionally, the Sarangchae area was used as a place for men to stay or meet visitors. Sarang yard located in front of Sarangchae is usually created mainly by borrowing the landscape of the outside. Yards are not densely filled with plants but a single tree or a small number of trees and shrubs are planted only. Unlike this traditional style, the yard of Inner Sarang-chae in Parkjinsagoga was richly decorated. This kind of style is also observed in Gyosudaek, Songhwadaek and Geonjaegotaek in Asan, Seong’s Old House in Changnyeong and Yong-Uk Lee’s House in Boseong, and they all show the transitional characteristics observed between the 19th century and mid-20th century. The introduction of these active gardens is observed mostly in Sarang yard among several gardens in houses, and changes in the gardening style are also observed at this point (Lee and Kim, 2006).

Ever since the garden of Inner Sarangchae in Parkjinsagoga was first created, its original form has maintained well until now (Fig. 5). The garden was created by Nasan Yong-Ha Park, the grandfather of the current eldest son (Fig. 6A) in the Japanese colonial period when he was in Bosung College, and he directly supervised the overall construction process, coming and going to Seoul. The work was initiated in accordance with the wishes of his father, Byeong-Don Park, but he himself expressed his opinions on and supervised the entire process from determining garden components and elements to planting. He met new cultures while he studied in Seoul and traveled Japan, and his new experiences seemed to affect the creation of the garden. According to Lee and Kim (2006), those who built gardens during the period were mostly from the upper class with power and wealth and had hobbies such as creating or collecting gardens and the number of those who directly experienced foreign cultures also increased.

Unlike traditional houses where planting plants was prohibited in the middle of gardens, planters were created at the center of the yard of Inner Sarang-chae. Even artificial moundings were created and trees and shrubs were densely planted. Compared to the size of the garden, it was quite huge, which might make some feel visually too heavy. Two planters were created freely, and the size of the planter on the western site was 16.0 m2, and that of the planter on the eastern side was 22.0 m2 (Fig. 6B). There was a narrow path between the two planters and the ∞-shaped traffic line of the garden was intended for people to look around the garden, which reminds of Japanese circuit-style gardens. The outer boundary of the planters was built with big natural stones and Japanese-style artificial mounding that were observed in the gardens of upper-class houses created around the time were introduced (Fig. 6B, C). The shape of artificial mounding gave dynamic images like natural geographical features and the height of the moundings on the western and eastern side was 1.0 m and 1.5 m respectively. In the hills, Pinus densiflora was planted and their lower part was covered with flowering shrubs. Meanwhile, natural uncut stones of different sizes were used in multiple places in the garden of Inner Sarang-chae and were placed along with trees and shrubs in several places on the artificial moundings as well as in the boundary of the planters, which reminds of Japanese stone gardens. The stones used in the garden were bluestones, one type of sedimentary rocks, collected from the same region. In between planters, 1 m-tall engraved stone monument written as ‘洗心’(clean your mind) in calligraphy of Yong-Ha Park was placed.

In the upper part of the artificial mounding created on the eastern side, an atypical small pond (2.3 m2) called ‘Sesimji’ was created, and natural uncut stones like the boundary of the planters were used. The bank of the pond was built using a rubble masonry technique (Fig. 6D). The pond created below the Pinus densiflora planted on the artificial mounding cannot be easily seen from the ground, but can be seen when standing on the hill. Natural stones were placed like stairs naturally for people to come up the stones and enjoy the pond. In traditional houses, square-shaped ponds with straight lines were created on the flat ground and were externally exposed and compared to them the pond in Parkjinsagoga seems to be affected by Japanese-style gardens from various aspects including its atypical shape, the bank built with natural stones, the small size and hidden location of the pond and the traffic line designed to enjoy the pond. Water was continuously supplied to the pond from the undercurrent beneath the ground and the nearby well also used the groundwater as a source. The well located on the southern side of the garden was known to be used not only as drinking water but also as water for bath in the bathroom built on the side of Daemun-chae.

Apart from the planters at the center of the garden, an one step-tall flat planter was created around its three walls, and tall trees (mostly broadleaf trees), flowering shrubs and flowering plants were planted in the planter and on the eastern side tall trees were not planted to enjoy the decorative wall.

While Sarang yards in traditional houses focused on emptiness, the garden of Inner Sarang-chae was very densely planted. Trees that had been preferred traditionally and those with curved branches were preferred in the garden. Among the tall tress planted in the early years of creating the garden, Pinus densiflora, Prunus mume and Acer palmatum still remain. Pinus densiflora was the most outstanding tree in the vegetation of the garden and out of the five Pinus densiflora trees only three trees are left today. One of the three trees withered to death but grew back from the same spot and the rest two trees did not seem to grow well. Since the three trees are on the eastern side today, the two dead trees are assumed to be planted on the western side of the planter. Tall trees on the western side include Chamaecyparis obtusa and Camellia japonica, and they are assumed to be planted after the Japanese colonial period. On the outer planter of the garden, deciduous trees such as Acer palmatum and Prunus mume were planted mostly in order to give a sense of the season. It was known that the current Prunus mume tree was re-planted using its side branch after the original one withered to death.

It is difficult to identify when exactly individual trees were planted, but Paeonia suffruticosa and Camellia sinensis seemed to be there even when the garden was created. According to the eldest son of the family, there used to be many Camellia sinensis trees near the well, but there is a tea tree garden that was created later in the back yard of Inner Sarang-chae. In line with that, Cheonggang Don-Byeong Park was known to enjoy the tea ceremony and there are several pieces of poetry and prose on tea in Cheonggangmungo (Miryang Park’s family Chung Heon Gongpa, 2006). The plantains that were planted in front of the narrow door in the early stage of creating the garden withered to death. Campsis grandiflora observed along the decorative wall on the eastern side was known to be planted long ago. The rest flowering plants and small shrubs observed today mostly seemed to be planted later. As the preference of house owners was reflected, the vegetation landscape of the gardens has also changed.

As discussed above, gardens were actively created not only in front of but also behind Inner Sarang-chae in Parkjinsagoga. The house was affected by Japanese styles and its garden was densely planted with trees in the middle of the gardens with tall walls surrounding the house, which showed transitional characteristics in modern times unlike traditional houses. In detail, dynamic hills that utilized the ups and downs of the ground were created centering on the atypical pond and planters at the center of the garden. In addition, trees were densely planted and natural stones were placed, which indicates that Japanese-style gardens back then were introduced and affected the garden.

The current vegetation planted in the gardens of Parkjinsagoga was surveyed and there were a total of 35 families and 57 species. There were 19 species of tall trees (40 trees), 20 species of shrubs (501 shrubs) and 17 species of flowering plants. The surveyed species were listed, and their location was marked (Table 1). In addition, the area of the house was divided into the back yard of Gotgan-chae, the vegetable garden and the back garden of Inner Sarang-chae, the garden of An-chae, the yard of Heotgan-chae, and the garden of Inner Sarang-chae, and their planting status was mapped individually (Fig. 7). On the planting maps, flowering plants were excluded, and tall trees and shrubs were marked only.

The number of tall trees planted in the garden of Inner Sarang-chae, the main garden of the house, was the highest, and a total of 22 species of trees, including Pinus densiflora, Prunus mume, Acer palmatum, Chamaecyparis obtusa, Sophora japonica, Camellia sinensis, Cercis chinensis, Paeonia suffruticosa and Campsis grandiflora. Pinus densiflora (3 trees), Prunus mume and Acer palmatum seemed to be the oldest ones as they are assumed to be planted when the garden was created. The height of Diospyros kaki and Acer pictum subsp. mono was over 7.0 m. Trees like Lagerstroemia indica, Lagerstroemia indica, Pinus densiflora f. multicaulis Uyeki, Punica granatum, Kalopanax septemlobus and Eleutherococcus senticosus were patch-planted (1–5 trees). Flowering plants were planted in different places along the walls of the house, and they are assumed to be planted later. The number of liliaceous plants such as Lilium amabile and Lilium amabile was the highest (5 species).

A bamboo forest was also created outside the outer wall of the house, but it was not listed here. Since the back side of Parkjinsagoga was an open and flat land, the bamboo forest seemed to be created to supplement in the early stage of building the house, but only a part of the forest is left today.

Walls were not just an accessory facility in traditional structures, but played a very important role in surrounding and protecting their inner spaces in terms of the construction of space (Lim, 2013). The stone walls that surrounded Parkjinsagoga have maintained well as they were first built in the late Joseon period, and since then they have been partially repaired. To ensure An-chae cannot be seen directly from Daemun-chae, inner walls were built to block people’s view and tall walls were built to separate the inner and outer spaces of the house. Basically, they were mostly earth and rock-fill walls, but their materials and patterns differed depending on the type of spaces. Four types of walls to the house were introduced (Fig. 8). The total length of the walls was 180 m, and the types of soil used to form the walls include the soil collected from rice paddies and red clay. Bricks, broken tiles and rocks were mixed together using a coursed masonry technique to form the body of the walls and tiles were placed on top of that, which shows not only the formality of upper-class houses but also their solidity and sophistication.

The wall of the yard of Inner Sarang-chae had the most decorative form among other wall types found in Parkjinsagoga (Fig. 8A-1, 2). The patterns and materials found in the middle of the wall made it look like a floral wall and harmonized with the garden. The upper and lower parts of the wall were decorated with broken pieces of channel tiles to make vertical striped patterns and flat broken stones were used in some areas. At the center of the wall, a pattern (35×30 cm) was added at intervals of 2 m. A square-shaped frame was created with bricks and the grid pattern - ‘亞’+’井’- was made inside the frame using broken pieces of channel tiles inside the frame. The frame was filled with soil. This grid pattern was also found in traditional latticed doors and densely-placed square shapes look like a net, serving as Byeoksa (repelling evil spirits; Heo, 1997). In addition, as the decorative elements used in windows and doors in the buildings of Parkjinsagoga were repeatedly used on the wall, giving a strong sense of unity and solidarity (Joo, 1979). Likewise, using the latticed pattern on the walls in the houses is a unique case, and the pattern seemed to be designed to symbolically express communication between the inner garden and the outside. Concave tiles were placed on the surface and a circle-shaped hole was made. Using the long side of channel tiles, a long band-shaped pattern was created across the entire wall, differentiating itself from other wall types. The wall in the space of Inner Sarang-chae visually surrounded the yard, which helped people better enjoy the garden created at the center and its secretive mood.

Meanwhile, the inner walls that divided the inner space centering on Inner Sarang-chae into An-chae, Outer Sarang-chae, Hangrang-chae and Chaewon were built high and were connected to the side wall of buildings. They perfectly separated each inner gardens (Fig. 8B-1, 2). Tile pieces were combined with earth and rock-fill walls, and flat broken stones and broken pieces of channel tiles were mixed and placed at a certain interval to highlight the band-shaped pattern. Compared to the floral wall in the garden of Inner Sarang-chae, its decorative impact was low but its well-ordered pattern gave a sense of modernity but at the same time restrained traditional beauty.

The wall bordered by an alley outside the gate, unlike other wall types in the old house, had big natural rocks piled from the bottom without any gap, and its upper part was made with the mixture of soil, rocks and tile pieces (Fig. 8C). Among other walls, the height of the wall was the highest, which was clearly intended to block the view of outsiders. In addition, unlike the one on the back side of the house, this wall was exposed to the outside, and for this reason the left and right sides of the tall gate were elaborately decorated to elevate the dignity of the old house. Similar to the decorated wall of Inner Sarang-chae, a band-shaped pattern was created using the long side of channel tiles and a circle-shaped hole was made on the surface of concave tiles in order to visually relieve the closed mood of tall walls and communicate with the outside. In the upper and lower parts of the wall, flat stones and tile pieces were used alternately, but its interval and density were controlled to some extent to give dynamic images to the long wall that might look boring.

The outer wall that was created on the back side of the house centering on An-chae, the platform for crocks and Gotgan-chae was created in an earth and rock-fill form using rubble stones (Fig. 8D). Compared to other walls in the old house, the wall had slightly rough and indigenous images, and its height was also the lowest, which indicates that people back then thought that this practical wall type was sufficient enough for spaces that were not exposed to outsiders.

The most widely used wall type observed in traditional houses built in the late Joseon period was an earth and rock-fill wall, and it mostly used rubble stones and a rubble masonry technique (Lim, 2013). Whereas, the walls in Parkjinsagoga, unlike typical rubble masonry walls observed in traditional houses, used tile pieces and bricks and introduced patterns and a coursed masonry technique, improving its sophisticated decoration. That is, considering that Korea’s traditional walls strongly reflected the social status of house owners (Joo, 1995), the walls in Parkjinsagoga with a significant level of formality gave several clues to the status of the family back then. Meanwhile, walls taller than 2.1 m perfectly separated spaces and also made people feel pressure and grandiosity (Yoo, 1991). The average height of inner walls in traditional houses built in the late Joseon period was 1.9–2.1 m, and the average height of outer walls was 1.6–2.0 m (Lim, 2013). Considering the results, the walls (more or less than 2.3 m) in Parkjinsagoga were a rare case of creating closed spaces.

The several characteristics observed in the walls in Parkjinsagoga, as discussed above, are related to the transitional changes of upper-class houses found in their architecture and gardens, and they also can be viewed as the characteristics of modern times when traditional norms started to change.

This study conducted on-site investigations and interviews to analyze the status the exterior space of Parkjinsagoga located in Cheonggwang-ri, Goseong-gun and discuss its landscape characteristics. This study focused on the composition of the exterior space, the types of gardens and planting and the landscape characteristics of walls, and examined its meaning as modern garden remains.

Parkjinsagoga is a modern Korean house that harmonizes traditionality and practicality, and is an invaluable material for research not only on architecture but also on changes in the gardens of upper-class gardens. Its exterior space can be divided largely into An-chae, Outer Sarang-chae and Inner Sarang-chae areas, and a garden was created in each yard (inner garden). In particular, one thing noticeable is that the yard of Inner Sarang-chae, unlike traditional gardening styles, was actively decorated. The garden was directly designed by Nasan Yong-Ha Park who experienced new cultures during the Japanese colonial period and he showed his special interest in creating gardens. At the center of the yard of Inner Sarang-chae, two atypical planters and artificial moundings were created and the traffic line of the garden was designed to enjoy them while walking. An atypical pond was created on one of the artificial moundings and trees and shrubs were densely planted. Natural stones were also placed. The style seemed to be affected by Japanese gardens. Apart from the planters at the center, a flat planter was created around the three walls of the garden. Tall trees (mostly broadleaf trees), flowering shrubs and flowering plants were planted to decorate the planter. These characteristics observed in the gardens of Parkjinsagoga are closely related to the transitional characteristics that traditional gardens started to show in modern times.

A total of 35 families and 57 species were planted in the gardens of Parkjinsagoga, and there were 19 species of tall trees, 20 species of shrubs and 17 species of flowering plants. The number of species planted in the garden of Inner Sarang-chae was the highest, and a total of 22 species of trees, including Pinus densiflora, Prunus mume, Acer palmatum, Chamaecyparis obtusa, Sophora japonica, Camellia sinensis, Cercis chinensis, Paeonia suffruticosa and Campsis grandiflora. Pinus densiflora, Prunus mume and Acer palmatum were assumed to be planted when the gardens were first created. Relatively young trees, shrubs and flowering plants were assumed to be mostly planted later. As the preference of house owners was reflected, the vegetation landscape of the gardens has also changed.

The walls in Parkjinsagoga were basically earth and rock-fill walls but their materials and patterns differed depending on the type of spaces. Four types of walls were introduced to the house. The wall of the yard of Inner Sarang-chae had the most decorative form among other wall types found in Parkjinsagoga and was utilized as a gardening element. The walls found in Parkjinsagoga mostly had a high level of formality and created closed spaces, which coincided with the changes observed in the architecture and gardens of upper-class houses built in modern times.

The status and landscape characteristics of the exterior space of Parkjinsagoga discussed in this study are expected to be utilized as a case for comparison in conducting studies on the efficient management of cultural assets and traditional gardens in modern times.

Table 1

Existing trees in the Parkjinsagoga garden

References

Heo, G 1997. The secrets of Korean traditional architectural decoration Seoul, Korea: Daewon Publishing.

Jang, BJ 2004. A Study on the ‘Han-ok’ of modern era in middle Kyungnam province. Master’s thesis. Kyungnam University, Changwon, Korea.

Joo, NC 1979. The design of Korean architecture Seoul, Korea: Ilji Publishing.

Joo, NC 1995. The beauty of Korean architecture Seoul, Korea: Ilji Publishing.

Kim, JS 2009. The study of Japanese-style garden characteristics in Lee, Hun-dong Garden, Mokpo, Korea. J Korean Inst Tradit Landsc Archit. 27(3):49-60.

Kim, JY 2015. Characteristic comparative analysis of Japanese garden in Korea. Master’s thesis. Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea..

Kim, SB, YS Yun, DS Kim. 2011. A study on the spatial composition principle and feature of Japanese garden, “Haechang Joojojang in Haenam Jeollanam-do. J Korean Inst Tradit Landsc Archit. 9(1):33-40.

Lee, HW, JH Rho. 2013. The formative characteristics of Seogo-jeongsa & Sameun-jeong byeolseo gardens in Toerori Miryang. J Korean Inst Tradit Landsc Archit. 31(4):70-83.

Lee, WH, YK Kim. 2006. A study on the transitional aspects in designing elements of Korean gardens that reflected during mid-19th century to mid-20th century. J Korean Inst Tradit Landsc Archit. 24(2):56-69.

Lim, DY 2013. A Study on the characteristics in the traditional houses fences of the late Joseon Dynasty. Master’s thesis. Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea.

Miryang Park’s family Chung Heon Gongpa. 2006. Cheonggang bookstore Jinju, Korea: Moon cheon gak at Gyeongsang National University.

Park, EY 2011. Modern division of the style of gardens presented in Korean traditional house yard. J Korean Inst Tradit Landsc Archit. 29(2):28-38.

Yoo, JH 1991. A study on the characteristics of fences on Choson period palaces. Master’s thesis. Konkuk University, Seoul, Korea..

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 1,382 View

- 10 Download

- Related articles in J. People Plants Environ.

-

Landscape Characteristics of

Sojinjeong Garden in Geochang2022 December;25(6)The Characteristics of Flora at Gogunsan Archipelago area in Jeollabuk-do2014 February;17(1)