|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 23(5); 2020 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: The elderly living in homeless living facilities for a long time suffer from various mental health problems. This study aims to determine the psychological, emotional, and social effects of a horticultural therapy program composed of gardening activities, which was designed based on the semantic structures of life for the homeless elderly living in the facilities for a long time.

Methods: A total of 12 subjects (6 in the control group and 6 in the experimental group) participated in the study. The horticultural therapy program consisted mainly of gardening activities, and a total of 16 sessions were conducted once a week for 16 weeks, 60–90 minutes per session. The subjects were tested to evaluate their self-esteem, depression, and horticultural activities. The data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon rank test, and Friedman test, which were nonparametric tests, conducted at a 95% significance level.

Results: First, in the case of self-esteem, a significant difference was found between the groups, 20.00 points (SD = 5.69) in the control group, and 25.50 points (SD = 3.73) in the experimental group (p = .034). Second, in the case of depression, no statistically significant difference was found in the posttest. Finally, in the case of the horticultural activity evaluation, the scores of most variables gradually and significantly increased during the program [Verbal interaction during activity (p = .006), Self-concept and identity (p = .006), Need-drive adaptation (p < .001), Interpersonal and social relations (p < .001)].

Conclusion: These results support that the horticultural therapy program could help the elderly improve psychological relaxation, emotional stability, and social relationships. In order to generalize the results, it is suggested to increase the number of subjects or conduct additional repetitive experiments in further research.

Methods: A total of 12 subjects (6 in the control group and 6 in the experimental group) participated in the study. The horticultural therapy program consisted mainly of gardening activities, and a total of 16 sessions were conducted once a week for 16 weeks, 60–90 minutes per session. The subjects were tested to evaluate their self-esteem, depression, and horticultural activities. The data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon rank test, and Friedman test, which were nonparametric tests, conducted at a 95% significance level.

Results: First, in the case of self-esteem, a significant difference was found between the groups, 20.00 points (SD = 5.69) in the control group, and 25.50 points (SD = 3.73) in the experimental group (p = .034). Second, in the case of depression, no statistically significant difference was found in the posttest. Finally, in the case of the horticultural activity evaluation, the scores of most variables gradually and significantly increased during the program [Verbal interaction during activity (p = .006), Self-concept and identity (p = .006), Need-drive adaptation (p < .001), Interpersonal and social relations (p < .001)].

Conclusion: These results support that the horticultural therapy program could help the elderly improve psychological relaxation, emotional stability, and social relationships. In order to generalize the results, it is suggested to increase the number of subjects or conduct additional repetitive experiments in further research.

Homelessness is the state in which one is deprived of the right to have a proper place to live, thereby living in an inappropriate or unsafe place for living without a specific home, mostly due to economic poverty (Sung, 2016). The homeless are excluded from not only leading a living worthy of a minimum of human dignity but also various opportunities, and their rights are violated with the social stigma of being labeled as potential criminals that threaten the rights of others, being socially excluded and discriminated in various ways (Sung, 2016).

The homeless in Korea have become a social issue in the Korean society due to the financial difficulties and high unemployment rates caused by the IMF crisis, which led to the beginning of the homelessness support services at the national level (Shin, 2019). According to the Survey on the Homeless 2016 by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, there are 11,340 homeless people in Korea, most (9,325) of which were living in facilities, and 21.4% of them were living in long-term facilities of at least 20 years (Ministry of Health and Welfare[MOHW], 2017). The homeless are undergoing great stress and many crises, but due to separation from family as a direct, primary social support system to solve these problems, they fail to adapt to the society or face intensified negative emotions like anxiety, depression and frustration (Kim and Won, 2000). According to Won (2003) who conducted a phenomenological study on the homeless, the homeless had five semantic structures about life: 1) ‘Unplanned life’ such as misfortune due to others, sense of freedom, laziness, and aimless life; 2) ‘Self-rationalization’ such as sense of defeat, resignation, resentment towards the support system, or lack of will; 3) ‘Superficial interpersonal relationships’ such as indifference, discord, hiding or avoiding each other; 4) ‘A sense of devastation’ such as mental helplessness, refuge, feeling regretful, demotivation, and lack of confidence; and 5) ‘The hope of new life’. Moreover, Won (2003) claimed that it is necessary to come up with nursing intervention plans based on these semantic structures of the homeless and promote and manage their health accordingly. Intervention studies on complementary and alternative therapies conducted to solve the mental health problems of the homeless are as follows. Park and Park (2015) performed art therapy for homeless people suffering from alcoholism, which is one of the common problems of the homeless, and found its positive effects on depression and abstinence self-efficacy. Moreover, Bak and Joung (2019) reported that imagery poetry therapy has the effect of providing psychological and emotional stability for the homeless. Moreover, Lee (2015) announced the effect of music therapy on self-esteem and interpersonal relationship building of the homeless. As such, despite many studies proving the intervention effects of complementary and alternative therapies on the homeless in various fields, there is insufficient research on horticultural therapy.

Horticultural therapy is a complementary and alternative therapy in which the participants take care of plants, explore their emotions in the process, build relationships with others, and improve their psychological and emotional stability as well as physical well-being and social relations (Sabra, 2016). In particular, horticultural therapy is applied for successful aging of the elderly, who not only obtain resilience from nature by encountering nature in the process of carrying out various horticultural activities, but also have more opportunities in social participation and the rehabilitation effect of physical functions as well as productive efforts through gardening activities (Nicholas et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2020). According to Grabbe et al. (2013) who had homeless women participate in horticultural activities, it was found that the activities relieved stress of the participants and improved their social inclusion and self-realization, while also reducing alienation from the society and pressure about homelessness under protection. Moreover, Niklasson (2007) reported that participating in a series of horticultural therapy programs regained self-esteem of the homeless, improved a bond with the community, helped them explore the negative emotions inside them as well as their ego while taking care of plants, and induced positive changes by driving creative talent. Furthermore, many studies, although not on the homeless, also reported the positive effects of horticultural therapy such as improvement of self-esteem and relief of depression. To begin with, as a result of applying horticultural therapy to participants living in or going to senior care facilities that are similar to the group of participants in this study, it was found that horticultural therapy alleviated depression and solitude (Chen and Ji, 2015; Chan et al., 2017; Yoon and Sung, 2017). As a result of conducting horticultural therapy on caregivers of the elderly with dementia facing depression due to various problems such as severance of social relations, it was found that the therapy alleviated depression (Kim et al., 2020). Moreover, according to Kim and Park (2018) who conducted horticultural therapy on middle-aged women, the therapy reduced depression and anxiety of middle-aged women and also promoted their ego-identity. As such, horticultural therapy brings positive changes to mental health problems like depression or ego-identity as a complementary and alternative therapy.

Accordingly, this study verifies the psychological, emotional and social effects of horticultural therapy by carrying out a program focused on gardening activities based on the semantic structures of the homeless about life proposed by Won (2003), examining the homeless elderly facing various mental health problems in addition to aging while living in a homeless living facility for a long time.

The objectives and methods of this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of G University (Approval No.: GIRB-A18-Y-0021), after which the study was conducted from March 15 to August 13, 2018 at a homeless living facility located in J city, Gyeongsangnam-do. The subjects were recruited on the public bulletin board in the living facility for 2 weeks starting March 15, 2018. The subjects were selected among the applicants by priority of the elderly who have lived in the facility longer according to the objectives of the study. We explained the purpose of research according to the research ethics code and conducted the study after obtaining consent for participation. The 12 final subjects were randomly divided into 6 subjects in the control group and 6 in the experimental group, and the experiment was conducted according to a two-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design (Table 1), after which the control group was provided with a gift as a reward for participation.

The horticultural therapy program was comprised of total 16 sessions carried out once a week from April 23 to August 13, 2018 to improve self-esteem and alleviate depression that has been mentioned as the main psychological and emotional problem of the homeless living in a facility for a long time. The detailed activities of the program to achieve the purpose were carried out based on the semantic structures of life that the homeless have proposed by Won (2003) to manage mental health of the homeless. The study by Won (2003) is a phenomenological qualitative research conducted based on sufficient literature analysis despite few cases to find interventions for the homeless living in facilities. It determined the semantic structures of the homeless to capture their psychological needs. The program was carried out with 1 facilitator (master’s program in horticultural therapy) and 3 assistant facilitators (1 in the doctor’s program and 2 in the master’s program in horticultural therapy), and each session was 60–90 minutes. The program was carried out in some parts of the garden within the facility (area of the garden where the program took place = approximately 30m2 in size, 20m long and 1.5m wide) and the program hall.

The program was designed with activities tending a garden prepared within the living facility, implementing various types of horticultural activities aside from gardening as plants require time to grow (Table 2). Moreover, in all sessions aside form the one in which gardening is the main activity, activities such as managing the garden (watering, removing weeds, thinning out, etc.) at the beginning, followed by the main activities for each session. The main crops cultivated were lettuce (Lactuca sativa), chili pepper (Capsicum annuum) and corn (Zea mays). Lettuce was seeded in Session 2, raised, and then planted in Session 5. Seedlings of chili pepper and corn were purchased and planted in Session 5. Moreover, lettuce and chili pepper were to be harvested and used by the subjects as food ingredients for mealtime within the facility in the gardening process. This was to compliment the subjects for contributing to the facility and encourage them to obtain sociality and a sense of responsibility.

The activities for each session are as follows. In Session 1 ‘Making a name tag’, the subjects were to decorate their names with pressed flowers to start over by participating in the horticultural therapy program. This was to fulfill the need for change in ‘The hope of new life (HN)’, the fifth semantic structure. In Session 2 ‘Sowing seeds’, the subjects sowed the seeds of lettuce and garden balsam and learned that the start of growing plants is in sowing the seeds. In association with that, the subjects could recall their own meaning of ‘beginning’ and give significance to a new life to fulfill the need of HN. In Session 3 ‘Picking dandelion shoots and making salad’, the subjects harvested dandelions they could easily find in the fields in childhood in the nearby fields and used them to make salad, which they ate together. In this process, the subjects talked about childhood memories and foods, and were reminded of their innocent selves from the past, unlike the way they are negatively distorting themselves today, losing the positive side. This activity was to change the negative mindset to positive as part of the second semantic structure ‘Self-rationalization (SR)’. Session 4 ‘Making paper carnations’ was also related to SR, intended to change the negative perspective as well as resentment towards the support system that the subjects had. The subjects were to use paper to make ‘carnations’ that are used in events to express gratitude such as on ‘Parents’ Day’ and rethink the meaning of family, recall good memories, and think about what they want to thank. Session 5 ‘Transplanting’ was planting lettuce seeded in Session 2 and chili pepper and corn prepared in seedlings in the garden. The subjects were to plan in which part of the space given to them to plant each crop and were notified that they must manage their own crops, along with how to manage them. This enabled them to live an active, planned life instead of a passive, unplanned life while living in the living facility for a long time, which is related to the first semantic structure ‘Unplanned life (UL)’. Session 6 ‘Earthing up and setting up a support (encouraging and supporting)’ was earthing up corn and chili pepper planted in Session 5 and setting up a support for chili pepper, which was for the subjects to support the growth of the crops they planted. This reminded them of how they are supported, changing the mindset toward a positive direction, such as resentment towards the support system in SR or indifference to others in the third semantic structure ‘Superficial interpersonal relationships (SI)’. Session 7 ‘Gomusin dish garden’ was decorating gomusin (traditional Korean rubber shoes) with which the subjects are familiar from childhood and planting oxalis. The subjects were to talk about happy memories from childhood and were reminded of their positive sides as they learned the language of oxalis (“I will protect you until the end”), thereby establishing the positive way of thinking about the support system. This was to help the subjects think positively about anxiety, sense of defeat, and resentment towards the support system in SR from living in the facility for a long time, as well as about the negative perspective and mental helplessness in the fourth semantic structure ‘A sense of devastation (SD)’. In Session 8 ‘Transplanting corn plants (lucky trees)’, the subjects recycled 2L bottles into flowerpots, wrote down the goals they want to achieve and the luck they have, and then transplanted corn plants. This was to resolve the issues in SD such as lack of confidence and negative perspective, and express their desire for change in HN, thinking that they can become a new person like the used bottle that was recycled into a flowerpot. In Session 9 ‘Making bouquets with wildflowers’, the subjects walked around the facility where the program was carried out and picked wildflowers, with which they made bouquets and gave to someone they want to thank among those living in the facility with them. This was to help change their negative perspective toward others in SI into a positive perspective. Session 10 ‘Making a flower ring’ was to make a ring with white clover, which is an activity they had experienced in childhood. They walked around the facility looking for white clover growing naturally in the surroundings and made rings with the flowers. This activity helped them recall pleasant childhood memories and good friends and talk about the games they had enjoyed when they were young. This reminded them of positive memories, leading their currently distorted and unstable self-image in SR toward a positive direction. Session 11 ‘Taking a walk in the arboretum’ was visiting ‘Gyeongsangnam-do Arboretum’ located nearby and taking a walk inside. This outdoor field trip was to remind the subjects of mental helplessness they feel as they live in one place for a long time, which is a problem in SD, and make them share their emotions about strolling in the natural environment and think about the meaning of rest. Session 12 ‘Harvesting plums and making plum extracts’ was harvesting plums grown in the facility and making plum extracts. This was to resolve the negative self-awareness that they have achieved nothing, which appears in SD. To this end, the subjects harvested plums and made plum extracts, while thinking and talking about what they have achieved in life. Session 13 ‘Dyeing nails with garden balsam’ was for the subjects to recall how they used to dye their fingernails with garden balsam flowers, which is a common childhood activity, by harvesting the garden balsam that was seeded in Session 2 and dyeing their nails. In the process, they were to think about the positive person they want to be and resolve to change into that positive person like the color of the nails changing as they are dyed. This was to change the negative perspective about themselves in SD into positive and fulfilled the need for change in HN. Session 14 ‘Making fruit punch’ was making punch with watermelon and Korean melon and eating it with others. The subjects talked about using watermelon and melon in a new way to make something new instead of eating it as it is and also about how they want to change in the future. This activity was to help them set up goals to become a ‘new person’ as a change to their currently aimless life in UL, thereby living an active, planned life. In Session 15 ‘Harvesting corn’, the subjects harvested, boiled, and ate corn together, talking about how they felt in the process of harvesting corn and the meaning of harvest. This was to change the negative thought about the topic in UL and SD, such as laziness, helplessness, and self-indulgent and aimless life that they cannot do anything into a positive way of thinking. Finally, in Session 16 ‘Cleaning up the garden’, the subjects cleaned up the garden they had used in the past sessions and looked back on the activities they had carried out. They also talked about what has changed before and after the program, carrying out a series of gardening activities in the past 4 months such as sowing seeds, transplanting crops in the garden, taking care of crops in their section, and finally harvesting the crops. They also set the goals to live an active, planned life, talking about how they would apply the successful experience from gardening activities to the rest of their lives. This was to end the aimless life they had in the past in UL and fulfill the need in HN by turning into a new person for remaining life.

We conducted a survey on gender and age to examine the demographic characteristics and used the self-esteem scale and depression scale to check the psychological and emotional changes of the subjects through the horticultural therapy program. Moreover, to verify the change of the experimental group in the process of carrying out horticultural activities, the items of the daily horticultural activity evaluation form were evaluated by the main therapist and assistants therapist in each activity based on discussion about the subjects.

The self-esteem scale used in this study was the Korean version of the scale by Rosenberg, which is a one-dimensional scale comprised of 10 items. The reliability of the Korean version of the self-esteem scale was analyzed by Lee et al. (2009), and it turned out that Cronbach’s α was in the range of .75–.87 depending on the group. The internal consistency, Cronbach’s α coefficient, was .548 in this study, which was low compared to the number of measurement items. As a result of testing the validity through principal component analysis, the factor loading was low, and 9 items except No. 8 with a different direction from other items were added up and used in the analysis. Accordingly, Cronbach’s α of this scale increased to .66, and the range of total score was 9–36 points, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem.

The depression scale used in this study was the Short Form Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) developed by Yesavage et al. and adapted and standardized in the Korean version by Kee (1996). 15 items are rated on a dichotomous scale of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, with the total score ranging from 0 to 15. Scores under 5 points are considered normal, 6–9 points severe depressive symptoms, and 10 points and above depression. Cronbach’s α of the tool in the study by Kee (1996) was .88, and that in this study was .75.

The horticultural therapy evaluation form was the tool developed by Oseas to determine the participation of subjects in group activities of occupational therapy as well as interest in work and capacity to evaluate horticultural activities, which was adapted and used by Koh (1999). This study performed observational assessment on total 6 items related to psychological, emotional and social aspects depending on the purpose of the study, such as ‘Participation’, ‘Interest and assistance’, ‘Verbal interaction during activity’, ‘Self-concept and identity’, ‘Need-drive adaptation’, and ‘Interpersonal and social relations’. Cronbach’s α in this study was .96. Higher scores in each item indicate that the participating attitude is desirable. The horticultural therapy evaluation form was applied only to the experimental group that participated in the horticultural therapy program, and 3 assistant therapists performed an observational assessment of the subjects after each session of the program. ‘Participation’ was rated on a 4-point scale from Reject (1 point), Just observe (2 points), Convince (3 points), and Voluntary (4 points), and ‘Interest and assistance’ from None (1 point), Disturbing others (2 points), Only interested (3 points), and Help the facilitator (4 points). The rest of the items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

The IBM SPSS 25 Statistics package was used for statistical analysis and graph drawing. For descriptive statistics of the measures for the general characteristics of the subjects, self-esteem, and geriatric depression scale as well as for comparison of pretest-posttest results, we used the nonparametric methods such as the Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon rank test, with a 95% significance level. For the results of each session measured using the horticultural therapy evaluation form, we conducted the Friedman test with a 95% significance level.

The subjects in each group were comprised of 4 men and 2 women, and their mean age was 72.4 (SD = 5.5) for the control group and 74.0 (SD = 5.1) for the experimental group. Moreover, the average years of living in the facility was 31.4 years (SD = 4.9) for the control group and 33.2 years (SD = 6.0) for the experimental group, with most of them living for a long time, at least 30 years on average. As a result of conducting a homogeneity test on the mean age and average years of living in the facility for the experimental group and control group, there was no statistically significant difference.

As a result of the preliminary test of homogeneity on self-esteem and depression of the subjects (Table 2), there was no significant difference between groups in all items. Accordingly, self-esteem and depression of the two groups can be presumed as homogeneous.

We analyzed the posttest mean difference between groups and pretest-posttest means of each group to determine the changes in self-esteem after the horticultural therapy program (Table 3). As a result of comparing the posttest mean difference between groups, the control group was 20.00 (SD = 5.69) and the experimental group was 25.50 (SD = 3.73), showing a significant difference between groups (p = .034). As a result of the pretest-posttest means of each group, the control group’s score changed from 22.00 (SD = 3.41) to 20.00 (SD = 5.69), showing a decrease but without statistical significance. On the other hand, the experimental group’s score increased almost with statistical significance from 23.17 (SD = 2.14) to 25.50 (SD = 3.73) (p = .071). Such a positive change in self-esteem was similar to the results of previous studies that conducted horticultural therapy on the elderly, which is the same age group as this study, although not on the homeless (Jeong et al., 2006; Han et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017). Moreover, the effect of horticultural therapy on improving self-esteem was also found in various subjects. Kim and Park (2018) reported that horticultural therapy on middle-aged women improved their ego-identity, and Eum and Kim (2016) discovered that horticultural therapy on schizophrenics increased their self-efficacy. In addition, Ha and Kim (2019) conducted horticultural therapy on multicultural adolescents and confirmed that their self-esteem has improved. As such, horticultural therapy is proved to be an effective intervention in improving self-esteem or related ego-identity and self-efficacy. This study also proved that conducting horticultural therapy significantly increased self-esteem of the subjects like previous studies. Low self-esteem of the homeless, the subjects of this study, is a factor that causes them to maintain homelessness and lose the will to work and rehabilitate, while also causing severe depressive situations. It is a key factor that makes homelessness become chronic, and thus it is necessary to develop a program to increase their self-esteem (Shin and Baek, 2010).

We analyzed the posttest mean difference between groups and pretest-posttest means of each group to determine the changes in depression after the horticultural therapy program (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in all results of statistical analysis. However, the control group tended to show an increase from 6.83 (SD = 3.97) to 7.33 (SD = 3.93) after the program, and the experimental group showed a decrease from 5.83 (SD = 3.13) to 4.83 (SD = 2.40).

This result did not show a significant change unlike the results of many previous studies on horticultural therapy reporting that depression of the experimental group decreased significantly. There may be two following reasons for that. First, analysis on the needs of the subjects in selection was not appropriate. Previous studies on the homeless were presenting ‘depression’ as one of the problems of the homeless (La Gory et al., 1990; Kim and Won, 2000; Cameron, 2010). Accordingly, this study also used ‘depression’ as an evaluation item based on previous studies. However, the depression of the subjects before the program was on the boundary between ‘normal level’ and ‘severely depressed’, with the control group 6.83 (SD = 3.97) and the experimental group 5.83 (SD = 3.13). This shows that, unlike the results of previous studies, the subjects in this study did not have a high level of depression as a major problem. Accordingly, this study could not find a significant change unlike previous studies on horticultural therapy. This is a limitation of this study that raises the need to undergo deliberation of the research protocol and survey items before selecting the actual participants is important so that the study on human subjects can be deliberated by the IRB. The limitation of this study is that it was inevitable to select the survey items based on previous studies accordingly. Therefore, further research shall seek ways to select survey items by determining the needs of actual subjects, in addition to using the results of previous studies in the selection process. Second, there was insufficiency in setting and attaining the detailed goals of the horticultural therapy program used in this study to alleviate depression. The program was organized based on the semantic structures of life by the homeless. Thus, the activities carried out were suitable for detailed goals that bring a significant change to the improvement of self-esteem, but insufficient for alleviating depression. In particular, depression of the homeless elderly may be caused by another aspect due to the special environment of being ‘homeless’ in addition to the depression generally experienced by the elderly due to aging (La Gory et al., 1990; Kim and Won, 2000; Cameron, 2010). Therefore, it is necessary in further research to more closely determine the cause of depression in the special group of ‘the homeless’, capture the needs of the actual subjects as mentioned, and set up more suitable detailed goals and methods accordingly.

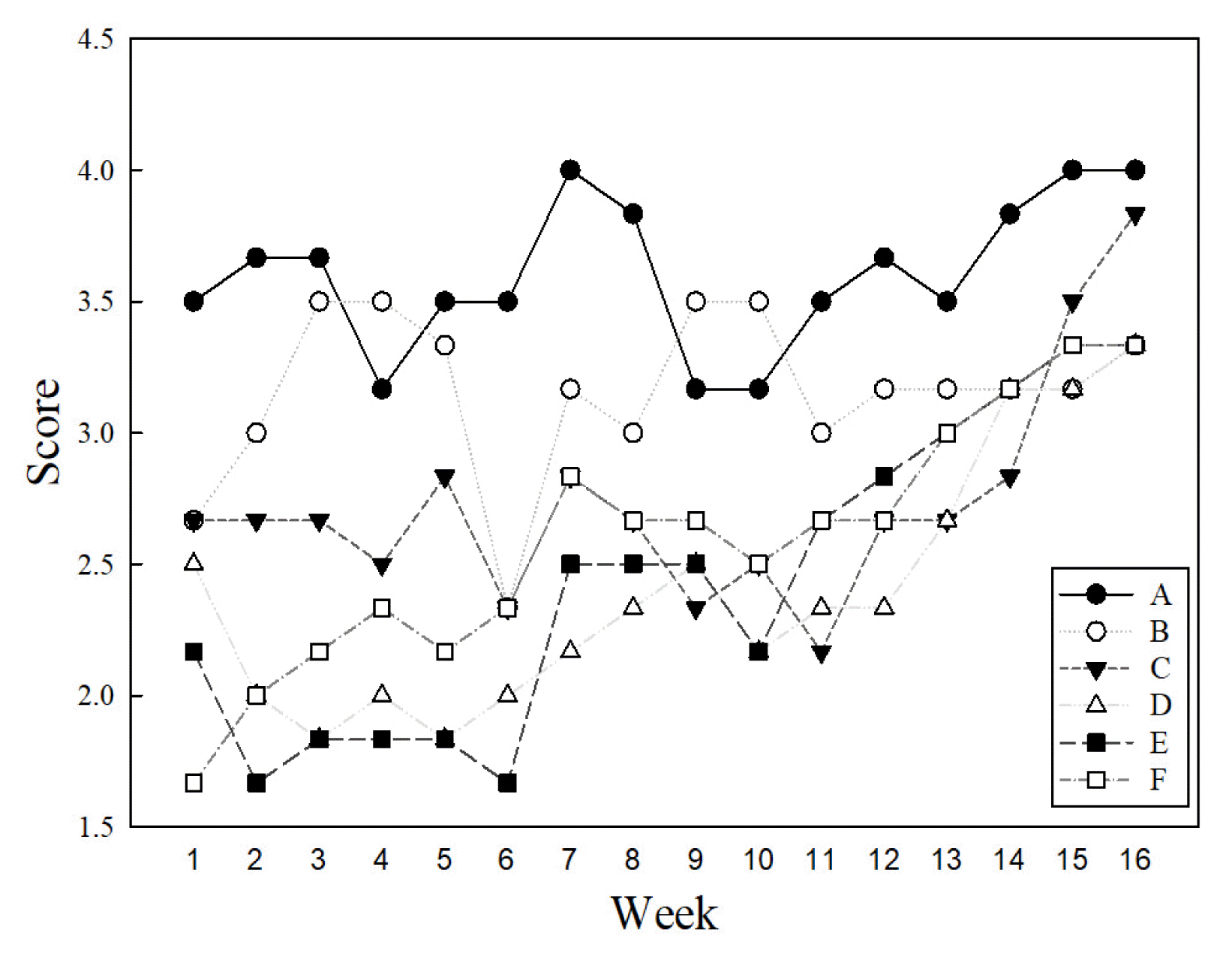

As a result of examining the change in the experimental group after the horticultural therapy program using the horticultural therapy evaluation form (Fig. 1), there was a statistically significant change after the program in all items except ‘Participation’ (Fig. 1A) and ‘Interest and assistance (Fig. 1B)’.

First, ‘Verbal interaction during activity (Fig. 1C)’ started as 2.67 (SD = 0.82) in Session 1 and changed to ‘Moderate-good’ at 2.17–2.83 until Session 14, then significantly increased to 3.50 (SD = 0.55) in Session 15 and finally to 3.83 (SD = 0.42) Session 16 (χ2 = 32.336, p = .006). Communication skills like this increased in Sessions 15 and 16 perhaps due to the fact that these sessions used more time for the subjects to talk about their changes or feelings about the activities as the final stage of the program.

‘Self-concept and identity (Fig. 1D)’ started as 2.50 (SD = 0.84) in Session 1, maintained 1.83–2.50 from Session 2 to Session 12, then increased to 2.67 (SD = 0.82) in Session 13, 3.17 (SD = 0.75) in Sessions 14 and 15, and 3.33 (SD = 0.82) in Session 16, showing statistical significance (χ2 = 32.336, p = .006). This is because Session 12 helped the subjects form positive self-awareness about their fruition, dealing with the negative perspective and mental helplessness in that they have achieved nothing in ‘Sense of devastation’ in the semantic structures about life (Won, 2003) that the subjects had had. Moreover, the activities that followed helped them set active and planned goals for their future and enjoy success in harvesting, thereby increasing the scores for ‘Self-concept and identity’ throughout the sessions.

‘Need-drive adaptation (Fig. 1E)’ was 2.17 (SD = 0.98), ‘A little’. in Session 1, but decreased to ‘None-a little’ to 1.67–1.83 in Session 2-Session 6. However, the score began to increase starting Session 7 (Mean = 2.50, SD = 0.55), showing a constant rise until the final Session 16 (Mean = 3.33, SD = 0.82) except Session 10 (Mean = 2.17, SD = 0.41), and this change was statistically significant (χ2 = 57.272, p < .001). This may be because before Session 7, the activities were focused on forming and tending the garden, but from Session 7, the subjects could participate in activities that they had never experienced before, thereby inducing their interest in the activities. In carrying out activities before Session 7, the subjects frequently showed responses such as “boring”, “uninteresting”, and “dull”, but in Session 7, they showed responses such as “new”, “fun”, and “interesting”. Further research can be conducted on the effects of the program based on the subjects’ responses to the activities to determine whether the different responses affected their concentration on the activities.

Finally, ‘Interpersonal and social relations (Fig. 1F)’ tended to generally increase from Session 1 (Mean = 1.67, SD = 0.52) to Session 7 (Mean = 2.83, SD = 0.75), but decreased from Session 8 (Mean = 2.67, SD = 0.52) to Session 10 (Mean = 2.50, SD = 0.55). However, the score increased constantly again from Session 11 (Mean = 2.67, SD = 0.52) to the final Session 16 (Mean = 3.33, SD = 0.52), showing statistical significance (χ2 = 43.295, p < .001). This may be due to the fact that the activities in Session 8 and Session 10 were concentrated on the semantic structures of the inner life of the individuals, not activities related to social support or collaboration with other subjects. However, while Session 9 was intended for change in ‘Superficial interpersonal relationships’ in terms of semantic structures of life, the cumulative indifference, pressure or discord from living in the facility for a long time led to inadequate results for expressing gratitude toward others in the facility, thereby reducing the score for ‘Interpersonal and social relations’.

In sum, ‘Participation’ and ‘Interest and assistance’ showed nearly perfect scores on average compared to other items from the beginning of the program, and thus the change in scores until the final Session 16 is not statistically significant. Other items generally showed an increase at a statistically significant level. This indicates that the horticultural therapy program has stabilized the psychological and emotional problems of the subjects in a positive way and improved their social skills. This result supports the qualitative research by Niklasson (2007), who discovered that horticultural activities of the homeless in community gardens alleviated the common psychological and emotional problems of the homeless and provided shared experiences through the group activities, thereby proving to be an effective intervention for forming a bond within the community. Moreover, Grabbe et al. (2013) conducted a horticultural therapy program at an adult day care center to promote mental health of homeless women and reported that the program improved social connectedness and self-realization and alleviated negative emotions, which was a result also found in this study. Furthermore, Lee (2019) conducted horticultural therapy on the elderly living in a facility for a long time although not homeless and discovered that the therapy improved their self-regulation ability, which is similar to the result of this study that the program has improved self-concept, independence and need-drive adaptation.

The homeless have various mental heath problems such as depression or suicidal ideation compared to others, and these mental health problems including severe depression and cognitive impairment stand out more among the homeless elderly as mental diseases become chronic along with aging. There is a need for various interventions such as counseling, therapy, and rehabilitation programs to solve these problems. Accordingly, this study conducted horticultural therapy on the homeless elderly living in a homeless living facility for a long time, as an exploratory study to verify the effectiveness of the horticultural therapy program as a solution to the mental health problems of the homeless elderly. Most of the subjects were the homeless elderly living in a homeless living facility for a long time, at least 30 years. The program implemented to the experimental group was comprised of total 16 sessions carried out once a week, 1–1.5 hours for each session. The results showed that there were positive changes with statistical significance in self-esteem of the subjects as well as the psychological/emotional and social aspects measured using the horticultural therapy evaluation form. However, there was no statistically significant change in depression. This result is due to the fact that severe depression mentioned as a major problem in previous studies was not found among the subjects of this study, which is due to the insufficiency in determining the needs of the subjects in the selection process and setting detailed goals related to depression in organizing the horticultural therapy program. Accordingly, it is necessary to organize a program for depression management of the homeless by determining more detailed causes of depression among the homeless as well as more detailed needs of the actual participants, thereby coming up with more suitable detailed goals and activities. These results support the psychological and emotional problem solving effect and social effect that are proved to be the effects of horticultural therapy on the homeless. They were also consistent with the results of previous studies on horticultural therapy for the elderly that are suffering not only mental health problems but also aging. This proved the potential of the horticultural therapy program as an intervention to solve mental health problems of the homeless elderly. However, the limitations of this study are that the results cannot be generalized due to the small sample size, and that there are environmental constraints as most activities were focused on gardening. Therefore, further research can verify the effectiveness of the program using a greater number of subjects, implement horticultural activities based on the preferences of each subject instead of focusing on gardening, create a manual for applicable programs in various situations, and prove the effects of horticultural therapy on the mental health of the homeless.

Fig. 1

Changes in the treatment group by horticultural therapy programs. A = participation; B = interest and assistance; C = verbal interaction during activity; D = self-concept and identity; E = need-drive adaptation; F = interpersonal and social relations.

Table 1

Protocols for horticultural therapy program (HTP) sessions

Table 2

Homogeneity test of subject’s characteristics

| Variables | Control (n = 6) | HTP (n = 6) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Self-esteem | 22.00 | 3.41 | 23.17 | 2.14 | .459NS |

| Depression | 6.83 | 3.97 | 5.83 | 3.13 | .818NS |

References

Bak, JH, MH Joung. 2019. The effects of simsang (imaginary-oriented)-poetry therapy on the psychology and emotion of the homeless. Asia-pacific J Multimed Serv Converg Art Humanit Sociol. 19(12):603-613. http://doi.org/10.35873/ajmahs.2019.9.12.001

Cameron, KL 2010. Older homeless women with depression. Doctor Dissertation. The University of Arizona, Arizona, USA.

Chan, HY, RCM Ho, R Mahendran, KS Ng, W Wai-San Tam, I Rawtaer, MKW Ng. 2017. Effects of horticultural therapy on elderly’ health: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 17(1):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0588-z#Sec16

Chen, YM, JY Ji. 2015. Effects of horticultural therapy on psychosocial health in older nursing home residents: A preliminary study. J Nurs Res. 23(3):167-171. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000063

Eum, EY, HS Kim. 2016. Effects of a horticultural therapy program on self-efficacy, stress response, and psychiatric symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 25(1):48-57. https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2016.25.1.48

Grabbe, L, J Ball, A Goldstein. 2013. Gardening for the mental well-being of homeless women. J Holist Nurs. 31(4):258-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010113488244

Han, KH, SM Lee, JK Suh. 2009. Effect of group horticultural therapy on the change of depression and self-esteem in older adult. J Korean Soc People Plants Environ. 12(4):1-12.

Ha, YJ, EA Kim. 2019. Convergence effect of horticulture activity program on self-esteem and school life adaptation of multicultural adolescent. J Digit Converg. 17(6):409-416. https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2019.17.6.409

Jeong, SH, MR Huh, BH Lee, JC Park. 2006. Effect of horticultural therapy on the self-esteem of geratric patients. J Korean Soc People Plants Environ. 9(4):79-87.

Kee, BS 1996. A preliminary study for the standardization of geriatric depression scale short form-korea version. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 35(2):298-307.

Kim, KB, JS Won. 2000. A study on family support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in homeless persons. J East-West Nurs Resear Seoul. 5(1):50-64.

Kim, KH, SA Park. 2018. Horticultural therapy program for middle-aged women’s depression, anxiety, and self-identify. Complement Ther Med. 39:154-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.06.008

Kim, YH, CS Park, HO Bae, EJ Lim, KH Kang, ES Lee, SH Jo, MR Huh. 2020. Horticultural therapy programs enhancing quality of life and reducing depression and burden for caregivers of elderly with dementia. J People Plants Environ. 23(3):305-320. https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2020.23.3.305

Koh, EH 1999. Effect of horticultural therapy on the rehabilitation of mentally retarded and physical disorder persons. Master’s thesis. Konkuk University, Seoul, Korea.

Kong, JH, SY Yun, BJ Choi. 2015. The effects of reminiscence-based horticultural therapy on institutionalized demented elders’ self-esteem and quality of life. J Korean Soc People Plants Environ. 18(4):305-309. https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2015.18.4.305

La Gory, M, FJ Ritchey, J Mullis. 1990. Depression among the homeless. J Health Soc Behav. 31(1):87-102. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137047

Lee, JH, HS Choi, SY Yun, BJ Choi, EJ Jang. 2017. Effects of horticultural activities and flower tea drinking based on reminiscent storytelling on demented elders’ cognitive and emotional functions. J Korean Soc People Plants Environ. 20(4):351-360. https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2017.20.4.351

Lee, JY, SK Nam, MK Lee, JH Lee, SM Lee. 2009. Rosenberg’ self-esteem scale: analysis of item-level validity. Korean J Couns Psychother. 21(1):173-189.

Lee, S 2019. Effects of a horticultural activity program based on validation therapy on the mental functions of elderly patients in nursing homes. J People Plants Environ. 22(6):611-619. https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2019.22.6.611

Lêng, CH, JD Wang. 2016. Daily home gardening improved survival for older people with mobility limitations: An 11-year follow-up study in Taiwan. Clin Interv Aging. 11:947-959. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S107197

Ministry of Health and Welfare. 20172016 Survey on the status of homeless people, etc Retrieved from https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=032901&CONT_SEQ=342798.

Nicholas, SO, AT Giang, PL Yap. 2019. The effectiveness of horticultural therapy on older adults: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 20(10):1351-e1.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.021

Niklasson, J 2007 Horticultural therapy for homeless people : What are the causes and conditions of homelessness, what needs do homeless people have and how can we best address these needs with a horticultural therapy program? Master’s thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; Uppsala, Sweden. Retrived from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:slu:epsilon-s-8317.

Park, JE, SG Park. 2015. A study on the positive art therapy program on depression and self-efficacy of homeless alcohol addiction. J Arts Psychother. 11(1):1-19.

Sabra, C 2016. Connecting to self and nature. J Ther Hortic. 26(1):31-38.

Scott, TL, BM Masser, NA Pachana. 2020. Positive aging benefits of home and community gardening activities: Older adults report enhanced self-esteem, productive endeavours, social engagement and exercise. SAGE Open Med. 8:2050312120901732. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901732

Shin, JS, JH Baek. 2010. The effect of self-esteem and social support on depression for middle-aged and elderly male homeless. J Korean Gerontol Soc. 30(4):1393-1407.

Shin, WW 2019. Development process and policy tasks of homeless assistance service in Seoul. Asia-pacific J Multimed Serv Converg Art Humanit Sociol. 9(11):964-972. http://doi.org/10.35873/ajmahs.2019.9.11.086

Sumalinog, R, K Harrington, N Dosani, SW Hwang. 2017. Advance care planning, palliative care, and end-of-life care interventions for homeless people: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 31(2):109-119. https://doi.org/10.5840/ncbq201717348

Sung, JT 2016. Study on Korea’s homeless problem-solving ideas. Law Rev. 57(2):61-88.

Yoon, MJ, KM Sung. 2017. The effects of a horticultural program based on cox’s interaction model on ability for daily life and depression in older patients with mild dementia. Korean J Rehabil Nurs. 20(1):12-21. https://doi.org/10.7587/kjrehn.2017.12

Won, JS 2003. The life experiences of the sheltered homeless. Korean J Adult Nurs. 15(1):56-66.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 5 Crossref

- 3,080 View

- 119 Download

- Related articles in J. People Plants Environ.