Introduction

Although community gardens were created in the first place with an aim to resolve the food issues and improve the health of the urban poor in overseas countries including the U.S., U.K. and Germany (Kim et al., 2012; Gyeonggi Research Institute, 2012, Son et al., 2013), they now recovered and promoted communities and have been being developed as a space to provide education and establish the culture during the process of cultivation and production of food altogether as well as fulfilling the function as a green space that controls the environment (Mustafa, et al., 1999; The Conservation Law Foundation et al., 2012; Tracy, 2012; Cohen et al., 2012). Community gardens are closely linked to the urban agriculture, which is contributing to securing safe food and the health of vulnerable groups under the spotlight of the world (De Zeeuw and Dubbeling, 2011).

Vulnerable groups refer to those who failed to satisfy the requirements in the life-changing cycle with the property owned by individuals, who are prone to be exposed to the social risks and in a poor condition not to overcome such risks (Shin, 2012). Under the Provision 1 of Article 2 of the Act on support for welfare and self-reliance of the homeless, etc., vulnerable groups who live without sustainable residence for a while are called homeless (Korea Ministry of Government Legislation, 2015). The homeless came to the spotlight of the society under the Asian economic crisis under the IMF (Lee et al., 2013; Gyeonggi Research Institute, 2006). Since the number of the homeless is not decreasing at the moment when South Korea has already overcome the economic crisis, it is necessary to provide continuous self-support programs for them, which may not be supported by the temporary sheltered housing. In particular, housing vulnerability may have negative impacts on safety and health and hinder the opportunity for independence and development of self-support capabilities, causing the vicious circle of not getting out of poverty (Nam, 2009).

Housing support projects have been conducted in various forms as the importance is recognized among the support projects for the homeless people. The housing support project for the homeless, which had been provided in a similar form as temporary sheltered housing or shared housing (Nam, 2010), started to provide supportive housing under the purchased rental housing project in 2014 (The Religious Sector Network to Support the Homeless, 2015). The supportive housing for the homeless has an operating system that provides all kinds of necessary services as well as safe residential spaces to the homeless people, by offering studio spaces which guarantee separate spaces for individuals (Nam, 2012).

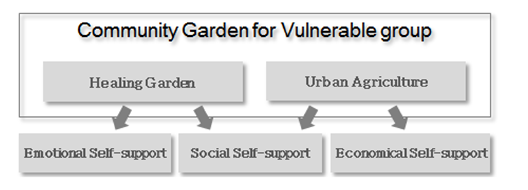

Since there are only a few cases on such supportive housing for the homeless and no researches on supportive housing services, it is necessary to conduct the researches on the necessary services and service areas for the homeless. If the community gardens are created as part of self-support services by applying the urban agriculture that is recently being expanded under the interests of the society, the gardens may be used as a space for the homeless tenants to interact with the nature and relax. Creating community gardens is expected to lay a foundation to not only improve the emotional self-support under the horticultural therapy but also achieve the social self-support based on the meetings and exchanges, and to improve the capability of economic self-support by tending the vegetable gardens, producing foods and learning techniques (Lee and Kim, 2015).

This research aimed to set the necessary principles for community garden design of supportive housing to enhance the self-support capabilities of the homeless, and use them as a basic data to design community gardens for effective self- support improvement program for vulnerable groups.

Research method

1. Research subject and method

This study aimed to set the principles for community garden design of supportive housing for the homeless to enhance their self-support capabilities so that the homeless people can be members of the society. It is necessary to plan to create the community gardens as a space for healing and producing to enhance the emotional, social and economic self-support of the homeless (Lee and Kim, 2014).

The research set the space planning principles depending on the subjects who would use the spaces by reviewing the relevant domestic and international resources to set the principles, and drew the necessary principle categories for space planning through FGI (Focus Group Interviews) with the specialists given the purpose of the use of community gardens.

FGI is one of the methods for in-depth group interviews with the participants who have clear sense of purpose even if they do not represent certain groups, and having intensive discussions over the given topics (Lederman, 1990). FGI is basically a method to listen to the opinions of the participants and learn from them within the form of a group interview, and the discussed ideas are the key data to the focus group (Shin et al., 2004).

This research selected 6 specialists for the focus group including three urban agriculturalists, two horticultural therapists and one rooftop garden designer, who have experiences in creating and operating healing gardens and community gardens and understand vulnerable groups. At first, the research asked the specialists to produce resources on necessary principles and matters to be considered for space planning for vulnerable groups to collect unlimited open answers, and conducted a discussion by comparing between the items acquired from the website and literature materials by the moderator and the items prepared by the specialists. The research elicited the principle categories for community garden design to improve self-support capabilities of vulnerable groups after two hours of discussion.

2. Analysis method

The research collected data from literature materials including the articles on the websites, research papers and books to set the principles for community garden design to improve the self-support capabilities of the homeless people. The literature used in data collection classified the categories of space planning principles from international and domestic resources and research papers based on the characteristics of the subjects, including the domestic relevant guidelines of ŌĆ£Universal design characteristics of ŌĆśDesign SeoulŌĆÖ public design guidelines for public spaces (Min et al., 009)ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Universal design guideline of homeless facilities in Seoul (Seoul, 2012)ŌĆØ, ŌĆ£Systemization of design characteristics of the residential environment and products developed under a universal design (Park and Lee, 2001)ŌĆØ, and the international guidelines of ŌĆ£Seven Universal Design Principles (Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, 2015)ŌĆØ, ŌĆ£Universal Design Principles and Model (Null, 2014)ŌĆØ, and ŌĆ£Product performance program (Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, 2003)ŌĆØ.

The principles for space planning according to the purpose of activities were established using the plans for healing gardens and the healing environment (Marcus and Barnes, 1999; Marcus and Sachs, 2014; Larson, 2004; Lee et al., 2014; Park, 2007; Kim et al., 2003; Kim, 2004; Simson and Straus, 1998) and the categories of design principles, and the principles for vegetable gardens were set from the space planning for urban agriculture by Carpenter and Rosenthal (2011) and Philips (2013).

The classified categories were divided again into subcategories, which were established as the principles after revision and supplementation through the FGI composed of the specialists for each area.

Conclusion and consideration

1. Space planning principles given the characteristics of subjects

The homeless people have a higher prevalence rate of mental disorder than ordinary people and the alcohol use disorder has a negative impact on social integration (Hahm et al., 2007; Shin, 2001). The patients with Schizophrenia may cause disorder in social function as well as the symptoms of delusion, hallucination, collapsed language and emotional dullness, more often attempt suicide than ordinary people, mostly fail to adjust to the society and experience recurrence and re-hospitalization (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The deterioration of health led to depression, influencing anger and self-efficacy. Since the decline in self-efficacy is closely linked to the will of self-support, it is necessary to support the homeless people to get out of homelessness based on social assistance and support (Kim et al., 2003). Community gardens for self-support of the homeless may supplement such physical, psychological and social vulnerabilities so that it is required to create the space for psychological stability and healing.

Universal Design (UD) is used as a guideline for design for the vulnerable many times. The concept of UD is used in convenient products, architecture, environment and services equitably provided to everyone regardless of disability, age, gender and language (Namgoong, 2011). Therefore, this research summarized the cases on UD to set the basic directions for community garden design for self-support of the homeless people (Table 1). The most applied principles of UD are the principles suggested by the Center for excellence in UD, including seven principles of equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, size and space for approach and use (Centre for Exellence Universal Design. 2003). Null (2014) suggested supportability, applicability, accessibility and safety as a basic principle for the UD principles and models.

Table┬Ā1.

Universal design principles for planning and design.

Seoul city adopted the concept of Universal Design in establishing the guideline for public design including welfare facilities, based on five principles of self-supporting, safety, perceptible information, healthiness and sustainability (Seoul, 2012). Other than that, economic feasibility, aesthetics and environmental friendliness were added to the existing principles and applied to the product design to evaluate universal design (Nakagawa, 2005). There were attempts to suggest the principles of acceptability, suability, informativeness, safety, comfortability and accessibility (Park and Lee, 2001; Connell et al., 2003), or the principles of functional efficacy, acceptability, efficiency of communication, comfortability and accessibility (Min et al., 2009) after adjusting the universal design principles to public design.

In terms of the commonly used principles, appropriate size for access and use has been mostly used, indicating that it is important to create a space that is easily accessed and used regardless of the physical conditions of the users. The second mostly used principles were flexibility in use and perceptible information. This showed that it is necessary to change or choose the space depending on the lapse of time, individual preference and user ability, and design the space, of which is easy to recognize the usage, directions or risks, regardless of the perception ability of the users.

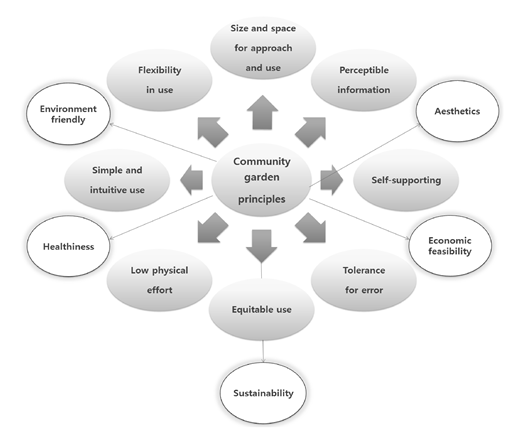

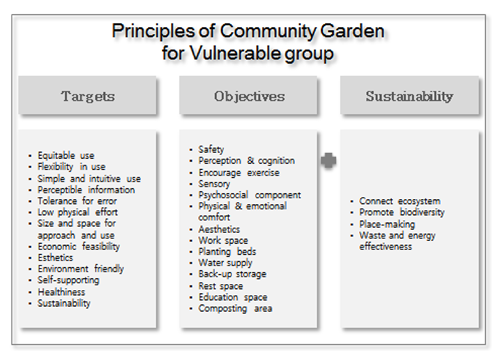

It is also necessary to approach to the mental issues aside from the physical and perceptional ones. The aesthetic or self- supporting aspects are very important in principle, despite with the lower frequency of use. In addition, since the support for the facilities for vulnerable groups is not easy to lead to maintenance and remuneration after establishing the facilities, it is necessary to consider sustainability and economic feasibility and to create environmentally friendly and comfortable spaces in the aspect of physical health (Fig. 1).

Therefore, 13 principled that applied universal design given the characteristics of the homeless people with difficulties in overcoming the physical, psychological, social and financial risks were set as the principles of space planning considering the characteristics of the subjects. The 13 principles are equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, size and space for approach and use, self-supporting, aesthetics, economic feasibility, environment friendly, healthiness and sustainability.

2. Space planning principles depending on the purpose of activities

It is required to plan the spaces for community gardens for improving self-support of the homeless depending on the purposes. However, as the emotional, social and financial levels of self-support of the homeless people using the community gardens are not the same and the purposes may change depending on the program progress, it is required to create the space given the circumstances. Healing gardens may become a space for relaxation and recovery, healing and exchange between the users for emotional and social self-support, and the vegetable gardens will serve as a space to produce foods that will contribute to the education of the base technologies for economic self-support and family finances. In this regard, the research came up with the principle categories necessary for planning the spaces for healing and vegetable gardens.

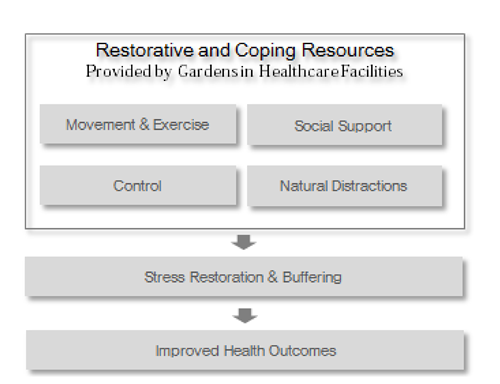

Marcus and Banes (1999) developed a model for healing gardens where the users can recover through light exercise by appreciating the nature, use the spaces that respect privacy and recover from stress and improve health through social support (Fig. 2). The self-support program using healing gardens aimed to i) continue the healing procedure by providing the users an access to large and small areas, individual and group areas, and planting areas within the gardens under the healing program; ii) give new confidence, technologies and understandings to the users as they face with others within the gardens; iii) strengthen the resilience as the gardens are used as a place to relax, recover and enjoy; and iv) provide amenity facilities so that the gardens can be used as a beautiful place by the program host and visitors (Simson and Straus, 1998).

With an increasing importance of quality of life, wellbeing and healing and health maintenance cost, the research started by Ulrich in 1984 is gaining ground that health management using plants has a positive impact on disease prevention and health maintenance. Larson (2004) from the service division of horticultural therapy of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum suggested 6 principles to apply to designing healing landscapes and gardens including diversity of space, use of plant materials, encouragement of physical activities, providing relaxation, minimizing negative elements such as noise and cigarette smoke and ambiguity.

Marcus and Sachs (2014) considered safety, security, privacy, accessibility, physical and psychological stability, change to positive interest, link to the nature, sufficient management and sustainability as key considerations for the general design guidelines for healing gardens.

Kim (2004) suggested the planning elements to plan the spaces for healing gardens for the people with mental disorder, given the disabilities in various senses and emotional aspects. Although the space planning for apartments used to focus on indoor, the apartment spaces started to be created for various purposes by gradually recognizing the importance of the external environment and Lee et al. (2014) elicited safe environment, therapeutic environment, comfortable environment, assistive environment, improved orientation, and social environment as planning elements to apply the planning elements of healing gardens to the external spaces of housing complex. The hospital environment, which used to prioritize the therapeutic functions, is starting to be created as a therapeutic environment as it changed to the patient-focused environment that satisfies the psychosocial requirements of the patients. In the example of introducing healing environment to the architectural planning for a womenŌĆÖs hospital, the planning elements were classified into the elements from the perceptional access of environmental perception, the elements from the structural access from the physical environment and the elements of healing environment from the psychosocial access (Park, 2007). Kim (2010) suggested exercise, perceptional and sensuous and psychosocial elements as the key elements to creating healing gardens on the rooftop of hospitals to maximize the therapeutic effects of horticulture.

The elements suggested as essential for designing healing gardens (Table 2) considered the physical and psychosocial aspects and did not exclude social exchanges by protecting comfortable and individual privacy. However, the plan for healing gardens contained the elements in the physical and psychological aspects and partly in the aspect of sociality, but the elements regarding jobs, which are the final stage of self- support for the vulnerable groups, have yet to be suggested. The prevocational rehabilitation program for those with chronic mental disorder conducted in healing gardens by Kim (2004) was limited to improvement of dexterity of hands and reduction of physical and psychological stress.

Table┬Ā2.

Elements/considerations of healing garden design.

For self-support of the homeless people, it is required to provide the works relating to producing and processing, which are one step ahead of healing, and education and technology that may lead to employment to the homeless. Such a goal of financial self-support is expected be accessed through urban agriculture. This is because domestic urban agriculture, which was started as hobby activities, is moving to the state that considers the economic aspect.

The awareness and use of urban agriculture may vary by country and region. Urban agriculture has been used for the purposes to not only offer food safety and local produces to individuals but also revitalize the local communities and improve the urban environment to become environmentally friendly and ecological (Table 3).

Table┬Ā3.

Principles/components of urban agriculture design.

Philips (2013) planned urban agriculture from the perspective of urban infrastructure and suggested 15 principles for the systematic thinking approach to urban agriculture. Philips suggested promotion of biodiversity, circulation of health and materials by food safety, social responsibility and economic benefits and opportunities. Holmgren (2002) pursued to overcome the environmental crisis and lead a sustainable life by suggesting 12 principles for management and design of natural resources to maintain health and wellbeing of the present and future generations as a concept of ŌĆśPermacultureŌĆÖ.

Hoe et al. (2013) suggested health, economy, culture, creating communities, values and importance of sustainability of education and environment to promote communities and make sustainable cities through community gardens. The elements and principles of the plans were able to be established based on the components of urban agriculture. Carpenter and Rosenthal (2011) provided the urban farmers who are planned to make vegetable gardens the necessary guidelines for the preliminary process of site preparation, components, design, creation and maintenance of urban agriculture.

It is able to know the concepts of healing garden and urban agriculture are changing depending on the need of the users according to the times. The necessary natural elements for the recovery of patients at hospitals are being used to create spaces that can lead to the active activities of experiencing, feeling and exchanging and showing the cases of making the healing environment in the residential areas beyond the hospitals. Such healing environments are based on the physical activities, considering comfortable environment and social psychology for relaxation and pursuing the spaces for safe use. Urban agriculture is suggesting the principles that can be applied in the size of city, region and individuals, gaining health from producing safe foods, receiving economic benefits and including the exchanges between the local communities and healthiness of urban ecology.

Therefore, the principles for community garden design depending on the purposes have been established in combination between the components of healing gardens and the components of urban agriculture depending on the purposes of emotional, social and economic self-support (Fig. 3). Basically, it is necessary to divide spaces with high availability for education for self-support program and work, and the spaces should respect the privacy for emotional self-support, provide relaxation for strengthening physical and mental resilience and improving health and be comfortable, beautiful, accessible and safe through plants. In addition, it is required to maintain the spaces well so that they can be used in a sustainable manner. In terms of the established principles of space planning, the users should be able to talk with each other and work together in the spaces for social self-support, and to learn and develop technologies which may lead to the production activities in the spaces for economic self-support.

3. Principles of community garden design for improving self-support for vulnerable groups.

The homeless need complicated and comprehensive assistance as they are vulnerable to physical, emotional, social and economic difficulties. If such issues can be overcome through community gardens using the residential area, it may become a huge contribution to self-support of vulnerable groups.

1) Space planning principles given the characteristics of subjects

To set the principles for community garden design for improving self-support for vulnerable groups, it is required to understand vulnerable groups, who are the research subjects. This is because community gardens should be built to meet the needs of the users. The universal design principles that may supplement the vulnerable characteristics of the homeless are essential to creating community gardens. Therefore, the principles with universal design was composed of 13 principles of 8 key elements of equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, size and space for approach and use and self- supporting assistance and 5 elements of aesthetics, economic feasibility, environment friendliness, healthiness and sustainability.

2) Space planning principles depending on the purpose of use

The design of community gardens vary by the purpose of use. This study set the purpose of community garden design as self-support of the users. Basically, community gardens have many users. This means that the conditions and requirements of each individual should be different. The spaces were planned with an aim of emotional, social and economic self-support including the physical and psychological aspects but the need of the users may change depending on the conditions of individuals and surrounding areas so that it is desirable to plan the spaces to be evolved to meet the changes. For the spaces for emotional self-support, it is required to design the spaces where the users can recover their senses using the plant materials to provide stability and comfortability with the nature and can engage in the physical activities. For social self-support, it is required to provide the spaces to create the spaces for meeting and exchange between the users given the psychosocial aspects as well as to protect the privacy of the individuals. Sociality can be improved with collaboration as well as meeting, greeting and conversation, and by learning skills and enhancing self- esteem through the growth process of the plants. Therefore, it is necessary to create ornamental gardens as well as vegetable gardens to tend and harvest.

3) Space planning principles considering sustainability

It is required to add the space planning principles that consider the ecological aspects such as circulation of material, reduction of energy and increase of biodiversity to guarantee sustainability of self-support programs using community gardens, except for the above considerations. Since the scope of the activities needs to be expanded as the level of self-support increased to the social and economic self-support, opening and expansion of the spaces for potential exchanges with the local communities should be included in the space planning principles, and the parts of social support including maintenance of space and securing specialists for improving the quality of the program should be included in the space planning principles (Fig. 4).

Summary

This study aimed to establish the principles for community garden design for improving self-support of vulnerable groups. To that end, the study considered the characteristics of the community garden users and the purpose of use of the gardens.

The research subjects were those in vulnerable groups and the universal design principles were applied after considering the characteristics of the homeless people who have difficulties in overcoming physical, emotional, social and economic risks. The 13 principles with universal design included equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, size and space for approach and use, self-supporting assistance, aesthetics, economic feasibility, environment friendliness, healthiness and sustainability.

Since the space planning principles according to the purpose of use of community gardens set the goal of emotional, social and economic self-support, the principles were established in combination between the elements of healing gardens and the elements of urban agriculture to meet the goal. The spaces should be divided with high usability for programs, respect the privacy of individuals, provide relaxation for strengthening resilience and improving health, comfortable and beautiful with plant materials, accessible and safe, and well-maintained and sustainable. For the ultimate goal of economic self-support, the space planning principles were established to develop the acquired technologies and lead to the production activities.

To secure sustainability of space and use, the principles included circulation of materials, efficient use of energy, promotion of biodiversity and connection with and assistance by the local communities.