Perception and Intent to Participate of Indigenous Residents on Rural Tourism and Urban-Rural Exchange in Namhae County, South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects require positive perception and participation of local residents. This study was conducted to analyze the perception and participation of indigenous residents and to propose ways to increase their intent to participate.

Methods

A survey was conducted to analyze indigenous residents’ perception of visitors, migrants, rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, and local government. The results were compared with the perceptions by visitors or migrants. In order to propose a plan for increasing their intent to participate, an equation composed of 5 explanatory variables was derived through stepwise multi-regression analysis.

Results

Indigenous residents were older, had a lower level of education compared to visitors or migrants, and perceived that the key motive of visitors was mainly enjoying the natural scenery and that having fun with family/friends was less important. Visitor satisfaction and intent to revisit were perceived to be lower. They were positive about the settlement of migrants. They generally rated tourism attributes low. They had a strong image of local agricultural products. They perceived that the awareness of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects was low, but the necessity was very high. For information source, they were less dependent on people around them and did not use much internet or social media. They perceived that the local revitalization was well performed, but the income from increased visitors was not as high as they expected. They strongly perceived the necessity of the local government’s role, but the level of its support was low.

Conclusion

Their perceptions tended to be consistently ‘undervalued’ overall compared to those of visitors or migrants. Their intent to participate can be effectively increased by preferentially improving awareness, partnership with migrants, and local government support focusing on income generation; reinforcing and proving the expertise of the department in charge; and spreading positive information about the success of major tourism resources.

Introduction

Rural tourism has become a major choice for economic development of rural areas and improved quality of life. Overseas travel is limited due to COVID-19, and as a result, domestic travel is receiving more and more attention, taking a new turn in terms of rural tourism. To reduce the gap between urban and rural areas since the 1990s, the central government and local governments have built infrastructures in rural areas by establishing laws and systems to promote rural tourism, supported various projects such as construction of green villages, and boosted exchange between urban and rural residents through urban-rural exchange projects to promote rural tourism. Rural tourism includes various experiential elements such as rural nature, farming, and rural culture (Yu et al., 2013). Urbanrural exchange refers to exchanging, trading, and providing human resources, agricultural products, culture, services, and information between urban and rural areas, and the type of urban-rural exchange most preferred by urban residents is exchange of recreation and leisure (Han, 2005), which shows that urban-rural exchange is a major part of community-based rural tourism (Park et al., 2021b).

Most countries view rural tourism as an alternative to supplement insufficient agricultural income (Moon et al., 2009). Two things are needed for the success and sustainability of rural tourism: one is to lead rural tourism to increasing nonfarm income for local residents, and the other is to satisfy the visitors and lead them to revisit. One of the key factors affecting visit satisfaction is the perception of tourism by local residents, and positive perception and participation of local residents are essential for success in the tourism industry (Allen et al., 1988; Lankford and Howard, 1994; Ritchie, 1988). Studies on local residents’ perception of tourism development worldwide suggested that it is necessary to accept the opinions and values of local communities for sustainable tourism (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014; Akis et al., 1996; Andereck et al., 2005; Getz, 1994; Gursoy et al., 2002; Hernandez et al., 1996; Lankford, 1994; McGehee and Andereck, 2004). Tourism development is carried out in many rural areas to increase income and revitalize the region, but tourism development without an appropriate plan and consideration of local values and environment also has a negative effect on the community in the social, cultural, environmental, and economic aspects (Sheldon and Abenoja, 2001). Therefore, to implement adequate policies, optimize benefits, and minimize issues, there is a need for awareness of residents’ perception of tourism and intent to participate (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014). However, most rural communities are currently in a complicated structure of long-term residents, owners of seasonal homes, and migrants who do not have the same perception of rural tourism (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014; Saxena, 2014). This indicates that it is necessary to explain their perceptions by distinguishing the different groups.

It is desirable that studies are continuously conducted on rural tourism and urban-rural exchange to establish policies in South Korea, but most of them are conducted at the national level or focus on generalization or theorization (Jang, 2013; Park et al., 2021b). When actually applied to rural areas, these generalized results may not match the situations of various different regions or not be effective. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously conduct studies at the regional level to implement region-specific rural tourism policies. Meanwhile, most studies conducted analysis from the perspective of tourists that are consumers, while very few focused on local residents from the perspective of agents that provide tourism services (Ulker-Demirel and Ciftci, 2020). This study is conducted to analyze the perception and participation of indigenous residents and suggest ways to increase the intent to participate based on the results of previous studies on the perception by visitors and urban-to-rural migrants of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange in Namhae County, Gyeongnam.

Research Methods

Site and subjects

Among rural areas in which the tourism industry is relatively activated, Namhae County, Gyeongnam was selected as the site. Namhae County is comprised of 75 islands (3 inhabited and 72 uninhabited) at the southernmost area of the Korean Peninsula, with the area of 357.6 km2. It has fine accessibility, connected to the land with Namhae Bridge, Noryang Bridge, and Changseon-Samcheonpo Bridge. It has a population of 42,650 as of June 2021, 16,375 (38.4% of the total population) of which are aged 65 and above, and visited by 4 million tourists a year (Namhae County, 2021). Indigenous residents were selected as the subjects. Indigenous residents are defined as long-term inhabitants that were born in Namhae Country and have since been living there. As of 2020, there are 1,145 migrants (about 2.6%) and the majority of the local community are indigenous residents (KOSIS, 2021).

Questionnaire design

According to the social exchange theory, the community’s perception of and attitude toward rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects are formed by the exchange of benefits and costs, taking the fundamental form of human interactions (Ap, 1992; Ekeh, 1974; Jurowski et al., 1997). Based on this concept, rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects can be explained by the perception and interaction of indigenous residents (supplier/host), visitors (consumer), migrants (partner), and government and local governments (supporter) related to the exchange of tourism resources, facilities, and services. Indigenous residents, who make up the majority of local communities, play an important role in a destination’s image and are often an integral part of the tourism experience (Chancellor et al., 2011). The more they support the tourism industry, the more amicable they tend to be, thereby providing more positive experiences for visitors and increasing the intent to revisit and word-of-mouth recommendations (Murphy et al., 2000). Therefore, their support is needed for success and sustainability of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, and support is regarded as the intent to participate (Ap, 1992; Jurowski et al., 1997). For that reason, it is necessary to increase indigenous residents’ intent to participate (Allen et al., 1988; Lankford and Howard, 1994; Ritchie, 1988). Intent to participate is affected by positive perception of tourism, which may lead to actual participation (Ahn and Yun, 2021; Park et al., 2021b).

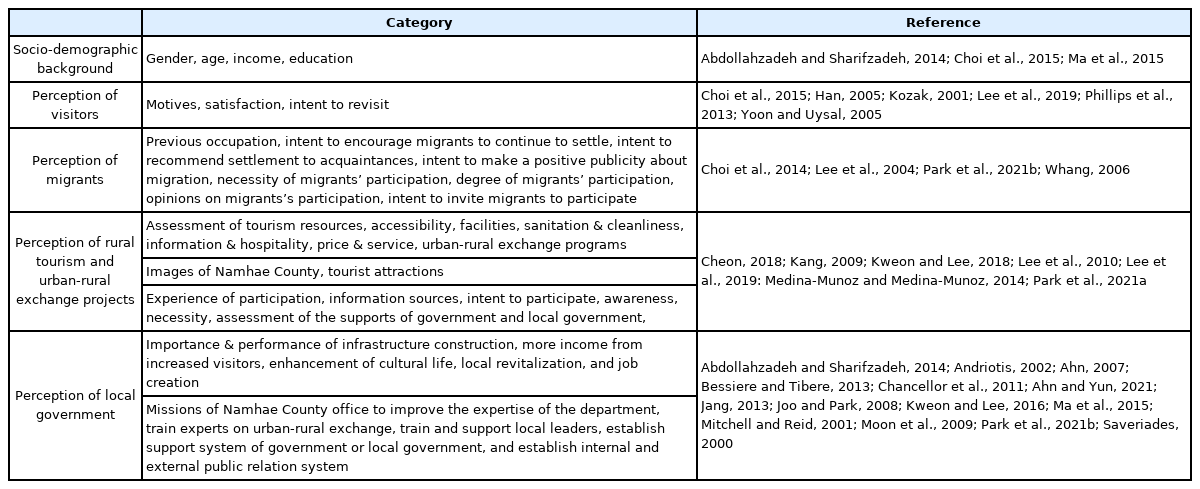

Based on the aforementioned theoretical background, we designed a questionnaire to analyze indigenous residents’ perception of visitors, migrants, rural tourism, urban-rural exchange projects, and the local government as well as their participation using the conceptual framework shown in Fig. 1. Questions were classified into sociodemographic background and perception of visitors, migrants, rural tourism, urban-rural exchange projects, and Namhae County Office (local government). For comparative evaluation, the questions were organized to have consistency with Park et al. (2021a) and Park et al. (2021b) (Table 1). Sociodemographic background included items on gender, age, income, and education. Perception of visitors included items on visiting motives, satisfaction, and intent to revisit. Perception of migrants included items on previous occupation, settlement, and migrant participation in projects. Perception of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects included items on tourism resources, facilities and services, urban-rural exchange programs, image and tourist attractions of Namhae County, participation experience, information source, intent to participate, awareness and necessity of projects. Perception of the local government included items on the importance and performance of the purposes of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects and necessity of missions (Andriotis, 2002; Bessiere and Tibere, 2013; Chancellar et al., 2011; Jang, 2013; Ma et al., 2015; Mitchell and Reid, 2001; Moon et al., 2009; Park et al., 2021b; Saveriades, 2000).

Perception and participation of indigenous residents on visitors, migrants, local government, and rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects in Namhae County, South Korea.

Scheme of questionnaire design for the perception and participation of indigenous residents on visitors, migrants, local government, and rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects in Namhae County, South Korea

Most items were designed in closed-ended questions rated on a nominal scale or a 5-point Likert scale (5 = Very satisfied/Strongly agree, 1 = Very dissatisfied/Strongly disagree). For visiting motives, the subjects were to provide multiple responses (first and second priority). Two items on the image and tourist attractions of Namhae County were open-ended questions designed to list up to 3 and 9 responses respectively.

Survey and analysis

The survey was conducted from November to December 2021. Indigenous residents were selected as surveyors to easily identify indigenous residents. The questionnaire were distributed to indigenous residents and responded in a self-administered approach. Data collected from 135 copies excluding those with inadequate responses were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. Variables related to the sociodemographic background and perception of visitors, migrants, and Namhae County Office were analyzed using frequency analysis or descriptive analysis. Most variables were analyzed using descriptive analysis in the perception of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects. Descriptive analysis and reliability analysis were conducted on variables related to tourism attributes such as tourism resources, facilities, and services (Lee et al., 2020). Variables related to the image and tourist attractions of Namhae County were analyzed using frequency analysis (Park et al., 2021a). Importance-performance analysis (IPA) was conducted to evaluate the expectations and performance of the purposes of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects (Kim and Huh, 2019; Martilla and James, 1977). Finally, correlation analysis and regression analysis were conducted in an exploratory method to suggest ways to increase the intent to participate. Independent variables with high correlation were included in multiple regression analysis to explain the intent to participate and analyzed in the stepwise method, and a regression model equation was derived with the independent variables that had highest explanatory power (Lee and Lim, 2018).

Results and Discussion

Socio-demographic background

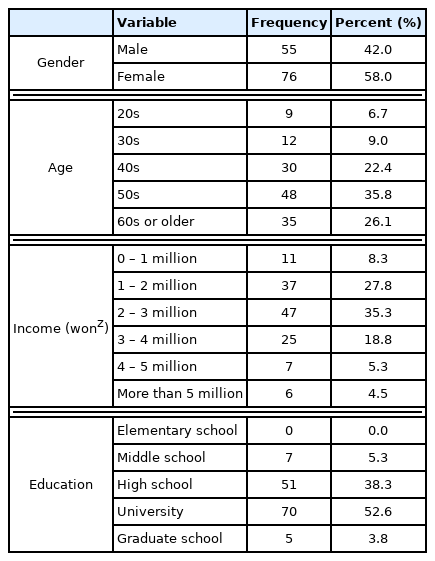

42.0% of the respondents were male and 58.0% were female (Table 2). 35.8% were in their 50s and 26.1% were in their 60s or older. 18.8% earned 3–4 million won, 35.3% earned 2–3 million won, and 27.8% earned 1–2 million won. 52.6% graduated university and 38.3% graduated high school. Compared to migrants (Park et al., 2021b), Indigenous residents were aged and had high income and low education levels. Along with the perception that business competency gets weaker as rural villages grow older, the skepticism about the possibility of success in community-based projects is also growing (Na and Choi, 2018). Aged residents have a low level of understanding as well as education effect, and thus it is relatively not easy to carry a project forward (Cho and Hwang, 2016). Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh (2014) stated that older respondents less perceived the benefits associated with economic aspects and activities related to physical attributes such as nature and village, and might feel uncomfortable with changes in life caused by physical activities such as tourism development. Andriotis and Vaughan (2003) claimed that people with low education levels do not perceive tourism benefits and are more likely to be negative about the effect of tourism.

Perception of visitors’ motives, satisfaction and revisit

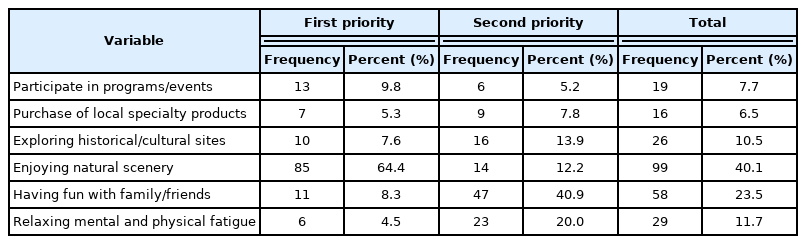

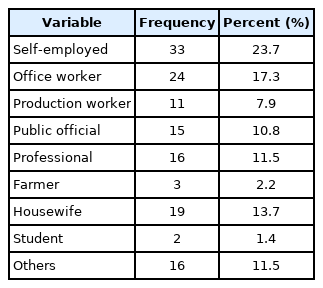

Indigenous residents perceived the motives of visitors as shown in Table 3. Enjoying natural scenery (64.4%) was highest for first priority, and having fun with family/friends (40.9%) was highest for second priority. In total, enjoying natural scenery (40.1%) was highest, followed by having fun with family/friends (23.5%) and relaxing mental and physical fatigue (11.7%). According to Park et al. (2021a), the actual visitor motives were enjoying natural scenery (36.9%), having fun with family/friends (34.8%), and relaxing mental and physical fatigue (13.9%), and 48.6% of visitors came with family. Comparing the two results, indigenous residents had a higher perception of enjoying natural scenery and lower perception of having fun with family/friends and relaxing mental and physical fatigue. This difference may result in setting an inappropriate direction for development and operation of tourism attributes and failing to effectively increase visitor satisfaction and intent to revisit. Lee (2004) claimed that the motive for participating in experience-based programs is family trips, gettogethers, or picnics. Jung et al. (2016) and Lee et al. (2020) revealed that the motives for rural tourism include healing and recovering of exhausted mind and body by enjoying nature. Visitor satisfaction and intent to revisit were perceived as 3.40 and 3.45 (Table 4). According to Park et al. (2021a), the actual visitor satisfaction and intent to revisit were 3.71 and 4.05, respectively. This shows that indigenous residents estimated tourism attributes of Namhae Country relatively low.

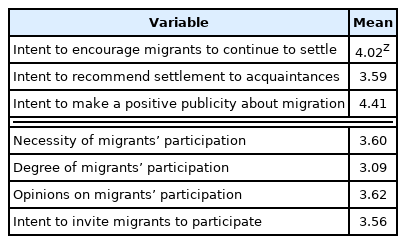

Perception of migrants’ previous occupation, settlement and participation

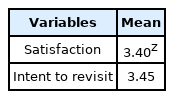

Indigenous residents’ perception of migrants’ previous occupation was highest for self-employed (23.7%), followed by office worker (17.3%) and housewife (13.7%), and was unusually high for others (11.5%) (Table 5). According to Park et al. (2021b), the actual frequency distribution of previous occupation of migrants was highest for self-employed (31.9%), followed by production workers (19.1%) and professionals (16.3%), and was low for others (2.8%). The relatively low frequency of self-employed, production workers, and professionals indicates that they might underestimate the potential skills of migrants. The intent to encourage migrants unsatisfied with settlement to continue to settle was 4.02, while the intent to recommend and make a positive publicity about migration was 3.59 and 4.41 respectively (Table 6). They had a positive attitude toward migrants’ inflow and settlement. They perceived that the necessity of migrants’ participation in rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects was 3.60 and that the current migrants’ participation level was 3.09. Opinions on migrants’ participation and intent to invite migrants to participate were relatively positive at 3.62 and 3.56. These results show that there is a high potential for forming partnerships between indigenous residents and migrants. Kim and Lee (2009) claimed that partnership among residents in rural tourism has a positive effect on the attitudes of residents. Moreover, Ko and Seo (2017) stated that, as a characteristic of rural community, the recommendation of others greatly affect the intent to participate in rural tourism projects.

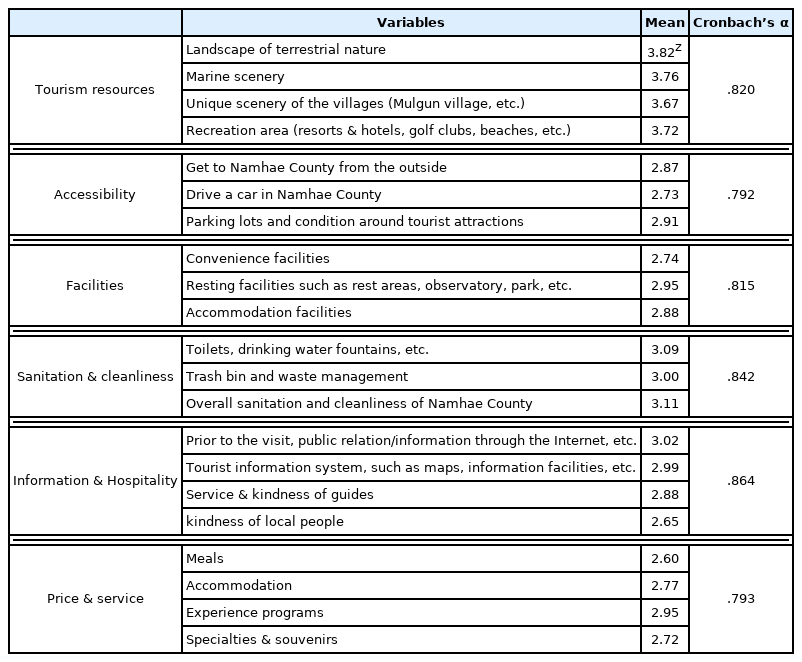

Perception and participation of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects

All groups of variables to assess tourism attributes showed acceptable reliability with Cronbach’s α value of 0.7 or higher as shown in Table 7 (Cheon, 2018; Kang, 2009; Kweon and Lee, 2018; Lee and Lim, 2018; Lee et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2019; Medina-Munoz and Medina-Munoz, 2014; Park et al., 2021a). Indigenous residents rated the tourism resources as excellent overall. Landscape of terrestrial nature was highest at 3.82, and the unique scenery of the villages was lowest at 3.67. This shows that the value of historical and cultural resources is perceived to be relatively lower. Accessibility was below average, with driving a car in Namhae County lowest at 2.73. Facilities were below average, with convenience facilities lowest at 2.74. Sanitation and cleanliness were about average. Information and hospitality were below average, with the kindness of local residents lowest at 2.65. Prices and services were below average, with specialties and souvenirs lowest at 2.72. Indigenous residents assessed that tourism resources were excellent, but facilities, prices, and services were below average: especially, prices and services were lowest among the attributes. According to Park et al. (2021a), the actual visitor satisfaction with most attributes was better as 3.5 or higher. In Park et al. (2021b), migrants’ assessment tended to be similar or better. In the assessment of urban-rural exchange programs, visit of cultural sites was highest at 3.84, wooden crafts experience was lowest at 3.19, and the rest were around 3.5 (Table 8). Livestock experience at a sheep ranch and visit of cultural sites such as German village were relatively high. The overall evaluation of the quality and operational expertise of urban-rural exchange programs was low at 3.21. Indigenous residents perceived that the quality and operational expertise of urban-rural exchange programs were relatively low, despite the excellent natural and cultural resources. According to Park et al. (2021a), the actual visitor satisfaction with urban-rural exchange programs and the overall evaluation of quality and operational expertise were 3.92 and 3.7 on average. As a result, the assessment of indigenous residents was lower than the satisfaction of visitors. The relatively low assessment indigenous residents have of tourism attributes can develop to negative perception and deteriorate the intent to participate. Thus, it is necessary to determine and improve the cause while also effectively providing indigenous residents with positive information about visitor satisfaction and revisit (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017; Saufi et al., 2014).

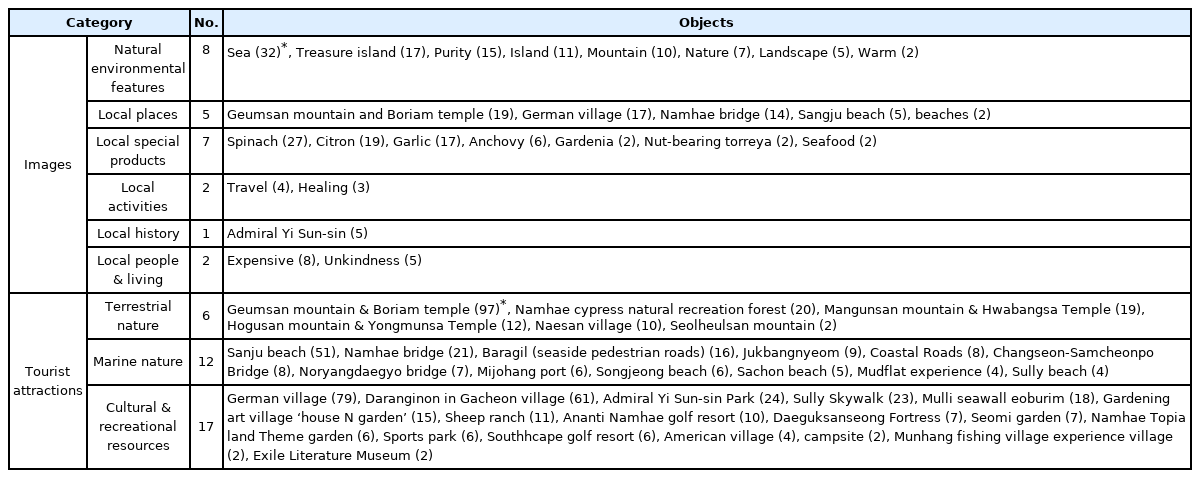

The results of analyzing the images of Namhae County and the tourist attractions recommended by indigenous residents are as shown in Table 9, and there was a difference from the perceptions by visitors and urban-to-rural migrants (Park et al., 2021a; Park et al., 2021b). The images that indigenous residents had showed lower diversity, and they particularly had a simpler image about natural environment features. Meanwhile, there were more extensive factors affecting image formation. They had a stronger image of local major agricultural products such as spinach, citrons, and garlic, and a less strong image of German Village developed for the tourism industry. Unlike migrants, they had the image that the prices was high and local people were unkind, which may be the result of the negative perception of the changes brought about by rural tourism (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014). Tourism development adopted to boost the community may rather increase local prices, destroy and damage local culture, expand consumerism, destroy the natural environment, create issues such as traffic congestion and waste disposal, and generate conflicts by forming various interest groups (Milman and Pizam, 1988; Sheldon and Var, 1984).

There were total 35 tourist attractions recommended, while in the previous study, visitors selected 17 tourist attractions as destinations (Park et al., 2021a). Tourist attractions with high frequency were Geumsan mountain and Boriam temple, German village, Daranginon in Gacheon village, and Sangju beach, which were similar to the perception by migrants and visitors (Park et al., 2021a; Park et al., 2021b). This difference shows that visitors did not have sufficient information about the attributes of tourist attractions or that the other tourist spots were not very attractive. Destination attributes may be a determinant with the highest correlation with destination attractiveness, which is why it is necessary to provide more abundant information about destination attributes in order to attract tourists (Caber et al., 2012; Medina-Munoz and Medina-Munoz, 2014; Park et al., 2021a). Moreover, destination attractiveness must be improved to attract and satisfy potential tourists (Kim and Perdue, 2011; Taplin, 2012).

Meanwhile, the images and tourist attractions related to rural experience villages created for rural tourism showed little or very low frequency. Moreover, there was almost no perception of the images or tourist attractions related to the unique local food, crafts, etc. This tendency was found similarly in the perceptions by visitors and migrants (Park et al., 2021a; Park et al., 2021b). Rural experience villages must be improved to attractive destinations related to the region’s unique and differentiated products and services, and local food and crafts unique to the region must also be developed (Bessiere and Tibere, 2013; Giampiccoli and Kalis, 2012).

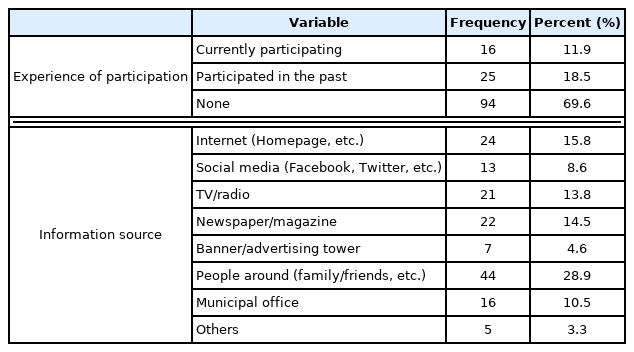

For experience of participation, 11.9% were currently participating, 18.5% participated in the past, and 69.5% had no experience (Table 10). Considering that the intent to participate was 3.41, and very willing and willing were 7.4% and 44.4% (total 51.8%), it is more necessary to increase the opportunity to participate. As for migrants, 9.1% were currently participating, 29.4% participated in the past, and 61.5% had no experience (Park et al., 2021b). Their intent to participate was 3.45, and very willing and willing were 10.5% and 44.8% (total 55.3%) (Park et al., 2021b). Considering that participation experience of indigenous residents and migrants were 30.4% and 38.5%, the opportunity to participate was equally provided without discrimination between indigenous residents and migrants, and actual participation was affected by the intent to participate (Ahn and Yun, 2021). Considering the frequency difference of those currently participating and those participated in the past between the two groups, the persistence of participation of indigenous residents was relatively high. This shows that participation of indigenous residents must first be increased for sustainable growth of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, and that it is necessary to develop urban-rural exchange programs operated by community collaboration (Park and Kim, 2010). For information source of indigenous residents, people around showed the highest frequency (28.9%), followed by the internet (15.8%), newspapers/magazines (14.5%), and TV/radio (13.8%). For information source of migrants, people around showed the highest frequency (33.9%), followed by the internet (20.5%), social media (12.5%), and newspapers/magazines (11.6%) (Park et al., 2021b). Compared to migrants, indigenous residents had lower dependency on people around, used less internet and social media, and depended more on TV, newspapers and banners. Considering the age of indigenous residents, it is necessary to not only come up with a way to expose them to new information sources but also effectively provide them with necessary information through conventional information sources while also increasing the opportunity to exchange and strengthen the partnership among members so that residents can share information among themselves (Ko and Seo, 2017).

Indigenous residents’ participation experience and information sources of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects in Namhae County, South Korea

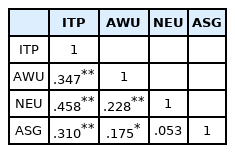

Indigenous residents’ intent to participate was 3.41, which was between average and willing (Table 11). Awareness was 3.00, necessity was 3.94, and assessment of the supports of government and local government was 2.81. Compared to migrants’ intent to participate (3.45), awareness (3.20), necessity (3.69), and assessment of the supports (3.61) (Park et al., 2021b), intent to participate was similar, awareness was lower, and necessity was higher, and assessment of the supports was lower. This indicates that while indigenous residents had relatively higher expectations for rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, they had low information accessibility, and as a result, they didn’t receive adequate support or sufficient benefits. Intent to participate showed a significant correlation (p < .01) with awareness, necessity, and assessment of the supports of the government and local government (Table 12). Since rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects include various activities to use the natural environment, settlement spaces, and agricultural spaces, they require voluntary participation and effort from local residents, for which it is necessary to first improve the perception of indigenous residents (Jang, 2013; Kang and Jeong, 2013). This result shows that intent to participation can be improved as awareness increases, awareness of necessity increases, and positive assessment of the supports of government and local government increases.

Intent to participate, awareness, necessity and assessment of indigenous residents of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects in Namhae County, South Korea

Perception of Local government

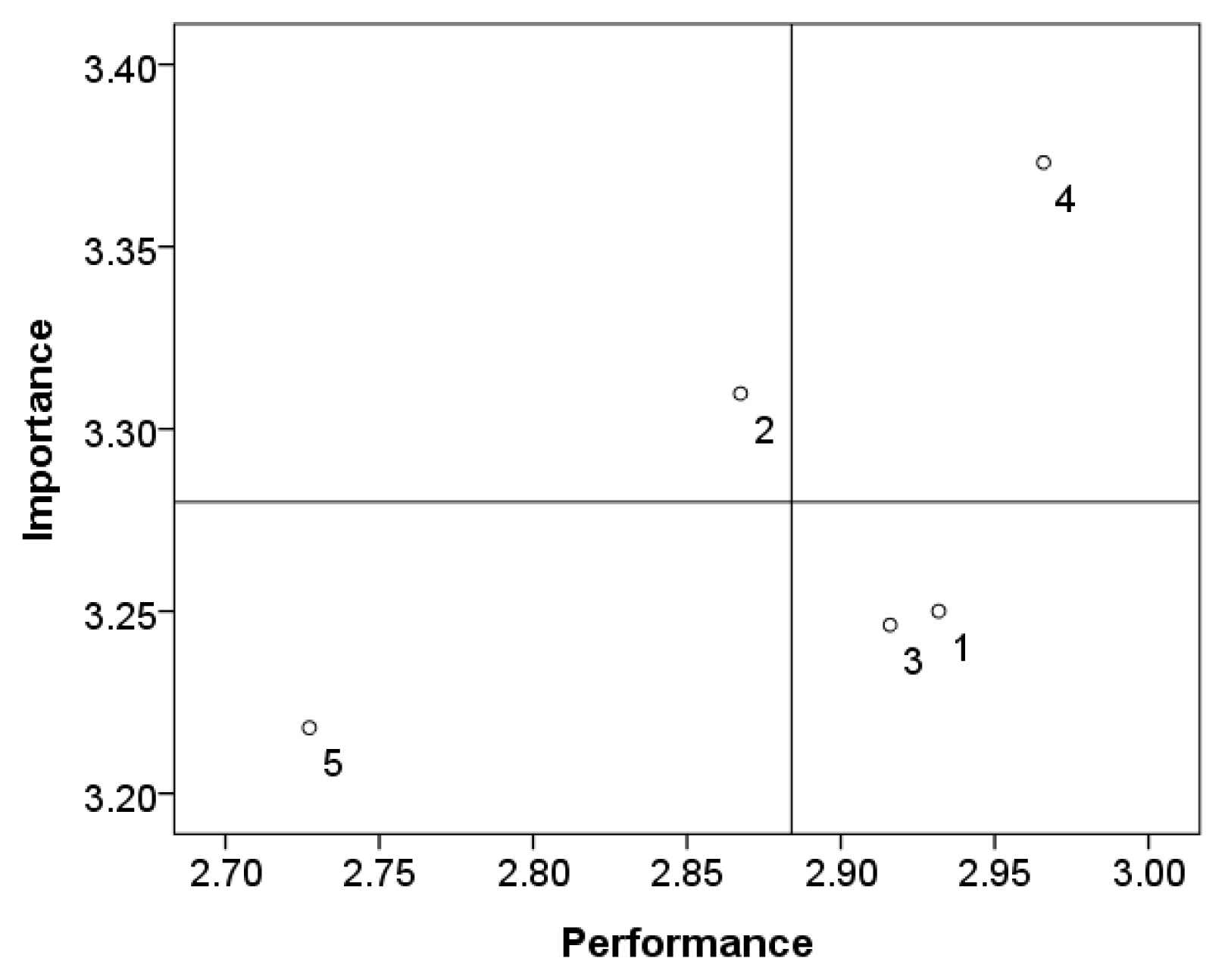

In the importance-performance analysis (IPA) of indigenous residents on the purposes of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, ‘local revitalization (4)’ is located in Quadrant 1 with high importance and performance (Fig. 2). ‘More income from increased visitors (2)’ is located in Quadrant 2 with high importance and low performance, ‘job creation (5)’ in Quadrant 3 with low importance and performance, and ‘infrastructure construction (1)’ and ‘enhancement of cultural life (3)’ in Quadrant 4 with low importance and high performance. ‘Local revitalization (4)’ is at ‘keep up the good work’ and thus needs to be kept at the current level, while ‘more income from increased visitors (2)’ is at ‘concentrate here’, which is top priority for improvement (Martilla and James, 1977). ‘Job creation (5)’ is ‘low priority’, and ‘infrastructure construction (1)’ and ‘enhancement of cultural life (3)’ are ‘possible overkill’.

IPA of indigenous residents on rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects in Namhae County: 1 = infrastructure construction, 2 = more income from increased visitors, 3 = enhancement of cultural life, 4 = local revitalization, 5 = Job creation.

Indigenous residents perceived that local revitalization was most important and has been well performed, and that income from increased visitors has not been generated as much as they expected. Importance of job creation, infrastructure construction, and enhancement of cultural life was relatively low, which means that excessive administrative and financial efforts were perceived for infrastructure construction and enhancement of cultural life. This shows that rural tourism should not only improve visitor satisfaction and revisit, but also provide a plan to expand the nonfarm income of local residents (Moon et al., 2009), and it is necessary to develop and implement projects that can benefit local residents even if it is small (Ahn, 2007). The more indigenous residents actually experience and feel the increase in nonfarm income, the more they would participate and support with positive perception. According to the social exchange theory, residents perceiving that tourism development benefits individuals tend to support tourism development and show a positive attitude (Ap, 1992; Jurowski et al., 1997).

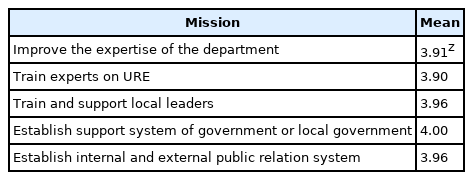

For missions that Namhae County Office must concentrate on, all the items scored 3.9 or higher, indicating that they were perceived as necessary (Table 13). Compared to migrants who responded an average of 3.7 to the same questions and needed internal and external public relation system more than expertise of the department in charge (Park et al., 2021b), indigenous residents had a stronger perception of the necessity of Namhae County Office’s role. This indicates that, compared to migrants, indigenous residents are more dependent on government and local government, while showing a passive attitude toward the projects. This tendency may be mainly due to the economic situation in which most indigenous residents have small farm or nonfarm income, but may also be the result of the fact that most rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects have been carried out by government-led administrative and financial supports (Ahn and Yun, 2021; Joo and Park, 208). Meanwhile, due to lack of information compared to migrants, indigenous residents may have perceived that Namhae County Office is not playing a relatively sufficient role.

Enhancement of intent to participate in rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects

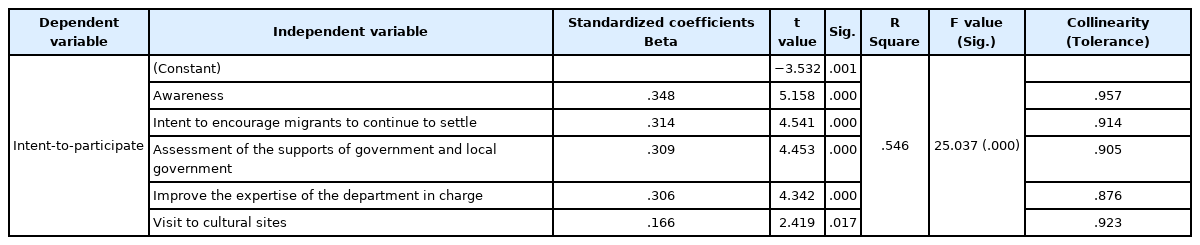

We conducted correlation analysis and stepwise multi-regression analysis in an exploratory method and derived a regression equation model with 5 significant independent variables to estimate the intent to participate with explanatory power (Table 14). For collinearity among the variables, the tolerance was much higher than .10 and thus there is no problem. R2 of the model was .546, indicating that the 5 independent variables were explaining 55% of the variance of the intent to participate (Lee and Lim, 2018). Comparing the standardized coefficients Beta of independent variables, the impact on the intent to participate was highest for awareness of projects, followed by intent to encourage migrants to continue to settle, assessment of the supports of government and local government, improvement of the expertise of the department in charge, and assessment of the visit to cultural sites.

Regression model of indigenous residents’ intent to participate with different variables related to rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects in Namhae County, South Korea

To effectively increase the intent to participate, first it is most effective to promote awareness of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects. Since low awareness serves as an obstacle in participation, this must be improved by education (Saufi et al., 2014; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2017). Learning and education related to tourism business must be continued regularly for a long time (Ahn and Yun, 2021; Cho and Hwang, 2016). Considering the aging of indigenous residents and major information sources, it is necessary to hold briefing sessions, public hearing, and panel discussions in addition to building a publicity system and implementing IT education. Second, it is necessary to form a positive perception about the quality of life and migrants and improve partnerships with migrants. There must be education to consider values such as nature, agriculture, and rural culture important in addition to improving the regional economy and living environment. Confidence and motivation for income generation through the community can be provided with education and field trips (Ahn, 2007). Reliable and positive information about rural tourism must be provided, while allowing the local community to share more information (Joo and Park, 2008). Since other people’s recommendations have a great impact on the intent to participate in a rural area where community norms are relatively strong (Ko and Seo, 2017), it is necessary to increase the chance to make contact through festivals and public hearings, thereby increasing the intent to participate and form partnerships between indigenous residents and migrants including neighbors (Ahn and Yun, 2021). Third, support plans associated with income generation of local residents must be established and implemented, and the outcomes must be proven. Indigenous residents have a stronger image about major agricultural products such as spinach, citrus, and garlic. According to the IPA, income from increased visitors is not increased as much as expected. According to the social exchange theory, residents benefiting from tourism perceive greater physical and economic benefits on average than those not benefiting (Milman and Pizam, 1988). Therefore, it is necessary to develop and implement projects associated with agricultural products that can benefit local residents even to a small extent (Ahn, 2007). Moreover, support plans must be established in the long-term view by accepting and reflecting the opinions, values, and needs of residents. The potential and fulfilled benefits and effects of those plans must be proved by constantly providing relevant information, and ultimately enable indigenous residents to experience and feel the economic benefits and effects (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014; Akis et al., 1996; Andereck et al., 2005; Getz, 1994; Gursoy et al., 2002; Hernandez et al., 1996; Lankford, 1994; McGehee and Andereck, 2004). Fourth, expertise of the department in charge must be enhanced and proven. The results in Table 13 show that indigenous residents are expected to have strong dependency on Namhae County Office, especially the department in charge, while also having doubts or dissatisfaction with the department’s expertise and services. Matters that are considered important when the intent to participate leads to actual behavior include confidence about the benefits such as nonfarm income and the ease of participation. Therefore, effective information, education, and consulting provided by the department in charge must include contents that promote awareness of the project’s benefits and ease of participation (Hwang and Cho, 2021), while also providing information that can directly induce participation (Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh, 2014). Meanwhile, it is necessary to consider improving satisfaction of indigenous residents with the department’s services and induce local residents to give word-of-mouth recommendations. Fifth, positive perception of best cases of major tourism resources must be expanded, and on the other hand, those cases must be linked to the nonfarm income of local residents. Interpreting the results of Tables 8, 9, and 14, it seems that indigenous residents perceived visits to cultural sites (German village, Gardening art village ‘house N garden’, etc.) as the best case of major tourism resources and improved their intention to participate as positively assessing the success and sustainability of the cases. Meanwhile, as an image that represents the region, their perception of major agricultural products was stronger, while their perception of German Village was less strong compared to those of visitors and migrants (Park et al., 2021a; Park et al., 2021b). This indicates that indigenous residents perceived tourism resources or images associated with direct income generation as more valuable. Therefore, effective administrative and financial support that can sustain the success of major tourism projects in the region is required, providing positive information about benefits rather than perceived costs by residents of Namhae County’s support (Joo and Park, 2008), and the benefits generated by it to spread widely in the region. According to the social exchange theory, residents who perceive that tourism development benefits individuals support tourism development and show a positive attitude (Ap, 1992; Jurowski et al., 1997). Moreover, festivals or public hearings must be held in major tourist business sites to promote connection or partnership between indigenous residents and tourist business operators. Positive perception and intent to participate improve in the process of sharing culture and experience, which as a result will be a driving force and a virtuous cycle that voluntarily revitalizes the region (Kang and Jeong, 2013).

Conclusion

Success and sustainability of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects require positive perception and participation by local residents. Perception and participation by indigenous residents that take up most of local residents are affected by the interactions of visitors, migrants, tourism attributes, and local governments. This study analyzed the perception and participation by indigenous residents in Namhae County and suggested ways to increase the intent to participate.

Indigenous residents were older and had a lower level of education compared to visitors or migrants. This may lead them to have a lower understanding and education effect, perceive less benefit, feel more uncomfortable about tourism development, and have a more negative perception. Compared to the actual perception of visitors, they perceived that the visitor’s motivation was mainly to appreciate the natural scenery, and perceived lower importance of having fun with family/friends and relaxing mental and physical fatigue. They also perceived lower visitor satisfaction and intent to revisit. They tended to rate the potential of migrants low, were positive toward their migration and settlement, and were likely to form partnerships with migrants. They generally rated tourism resources, facilities, prices and services, and urban-rural exchange programs lower. They had a strong image about local agricultural products and also an image about expensive prices and unkindness. They had a weak image about rural experience villages created and supported by government and local government or ranked them low in recommended tourist attractions. They rarely perceived the region’s unique local foods and crafts that lead to nonfarm income.

They had low awareness of rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects and assessed the government and local government supports low, while they perceived the necessity of the supports high. For information sources, they were less dependent on people around, used less internet or social media, and obtained information through conventional methods such as TV, newspapers, and banners. They perceived that, in rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, local revitalization was most important and well performed, but did not perceive that income due to increased visitors was as high as they expected. Expectations related to job creation, infrastructure construction, and enhancement of cultural life showed relatively low importance, and they especially perceived that excessive administrative and financial efforts were put into infrastructure construction and enhancement of cultural life. They strongly perceived the necessity of Namhae County Office’s role.

In sum, compared to the perception by visitors or migrants, the perception of indigenous residents was consistently ‘undervalued’ in terms of tourism attributes, visitor satisfaction and revisit, and government and local government supports. This tendency may give negative perception about participation. Positive perception may induce support and participation in rural tourism and urban-rural exchange projects, and improving support and participation may be regarded as increased intent to participate. Indigenous residents’ intent to participate can be effectively increased by the following suggestions. First, this can be done by promoting awareness of the projects, providing positive or specific information for participation. Second, it is necessary to increase indigenous residents’ intent to encourage migrants to continue to settle, which requires their positive evaluation of quality of life, sense of community, and partnership. Third, there must be improved government and local government supports, where it is important to plan and implement supports that meets the opinions, values, and needs of indigenous residents as well as supports associated with income generation. Fourth, to improve the expertise of the department in charge, it is necessary to reinforce and prove the expertise of the department in charge, and the service provided should include information about the benefits of the projects, ease of participation, and participation itself. Fifth, success can be sustained by spreading the positive perception of best cases in major tourism resources. Positive information on the benefits of the projects must be provided rather than the costs, and those benefits must induce support from local residents in association with their nonfarm income.