Forest therapy program reduces academic and job-seeking stress among college students

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Recreation or activities in forest are regarded as therapy. Many forest therapy programs have been developed and assessed in the domestic. This study was conducted to investigate the effect of the forest therapy program on academic and job-seeking stress in college students.

Methods

Thirty five subjects were selected as the experimental group and 25 as the control group, and 29 subjects in the experimental group and 11 in the control group participated in the follow-up test to verify the persistence of stress reduction effects. The forest therapy program was carried out once a week for 2 hours each from September 4 to December 4, 2018, adding up to total eight sessions.

Results

The experimental group showed statistically significant reduction in both academic stress and job-seeking stress, whereas the control group did not. For the persistence of the forest therapy program, the experimental group did not show a statistically significant difference between the posttest and the follow-up test, and thus the stress reduction effect was maintained.

Conclusion

This study proved the reduction of academic and job-seeking stress in forest therapy programs and the persistence of the stress reduction effect of the forest therapy program. The result is consistent with the Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) that shows the stress reduction effect of nature. In addition, it has significance in that it has verified that the program using the forest on campus can reduce stress of most college students.

Introduction

College students suffer from job-seeking stress and academic stress due to the jobs crisis. The employment to population ratio of the youth aged 15–29 is merely 42.7%, and their unemployment rate is constantly increasing from 7.5% in 2012 to 9.5% in 2018 (Statistics Korea, 2018). This is the highest unemployment rate since the currency crisis in 1999. Accordingly, ‘career after graduation’ (60.0%) became the No. 1 concern of college students, followed by ‘studies’ (25.2%; Ministry of Education, 2017). According to the National College Mental Health Survey’ conducted on 2.78 million college students nationwide, academic and career problems were the biggest stress suffered by college students (Kwon, 2017).

Job-seeking stress in college years is associated with academic stress, and students are facing anxiety about the future, stress related to employment, depression, mental pressure, hopelessness, and fear (Bae and Kim, 2016; Choi and Lee, 2014; Lee and Bae, 2019; So and Park, 2016).

As such, stress suffered by most college students in Korea is a process of adaptation to harmonize the body and mind according to the new state since it is impossible to maintain the current state (Hwang, 1998). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined stress as a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being. Job-seeking and academic stress that is most commonly faced by students is known to cause insomnia, deterioration of concentration and depression, and have a negative effect on career decision self-efficacy, career maturity and career compromise (Kang, 2006; Lee and Kang, 2011; Shin and Jang, 2003). Thus, it is most necessary to relieve stress of college students. Suh (2011) reported that how one copes with stress determines life satisfaction and subjective happiness more than the stress itself. However, college students are relieving stress inappropriately, such as by drinking and smoking (16.6%), giving up or avoiding the cause of stress (5.7%), and eating (12.2%; Chu et al., 2001).

Studies on forest therapy activities are conducted as a method to relieve stress. Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) argued through the attention restoration theory that people today are exposed to attention fatigue, and the natural environment recovers the fatigue. Forest environment is reported to have positive effects in terms of Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and electroencephalography (EEG; Lee et al., 2009). Moreover, environments with high greening ratio like the forest can be perceived as a restorative environment by individuals and anticipate the effect of emotional recovery as well, thereby having a positive effect on recovery of stress and negative emotions (Song, 2011). As such, the forest environment has the effect of relieving stress as it is. Studies are proving that forest therapy activities in the forest environment have positive effects on psychological stress, psychological fatigue, physical fatigue, stress resistance, and stress index (Park, 2015). Park (2019) reported that forest therapy programs increase serotonin and reduce social and psychological stress as well as depression, anger and fatigue. This indicates that the forest environment and forest therapy programs have positive effects on stress. However, additional research is needed on the effects of forest therapy programs on academic and job-seeking stress, as there is insufficient research on the persistence of the effects.

Accordingly, this study set the following hypotheses: “The experimental group that participated in the forest therapy program will show a decrease in academic and job-seeking stress compared to the control group” and “The forest therapy program will show persistence in reducing academic and job-seeking stress”. In addition, this study also investigates the change in stress of college students as well as persistence of stress when participating in the forest therapy program.

Research Methods

Subjects and site

This study was conducted on college students attending C University in Cheongju to determine the effects of the forest therapy program on stress of college students. There were 60 subjects divided into the experimental group (35 subjects) and the control group (25 subjects) to determine the effects of the forest therapy program. Moreover, the follow-up test was conducted to examine the persistence of the stress reduction effect after the program. Six subjects in the experimental group and 14 in the control group dropped out and thus only 29 in the experimental group and 11 in the control group participated in the follow-up test. The selected site was the lawn surrounded by trees on the campus of C University (Fig. 1). The area of the site is 7,746.8 m2, and it has little mobility of outsiders, a broad view, and a great screening effect by the trees. Gatersleben and Andrews (2013) argue that areas with a broad view and a screening effect by trees tend to have the greatest healing effect. The main species (42 trees) is Chamaecyparis pisifera (Siebold & Zucc.) Endl. and the average diameter of basal height is 33.95(±8.08) cm and the average height is 14.07(±2.52) m. Other species include broadleaf trees such as Prunus yedoensis Matsum, Zelkova serrata, and Quercus aliena Blume, and needleleaf trees such as Pinus densiflora, Juniperus chinensis, and Pinus koraiensis.

Procedures

The forest therapy program was carried out once a week for 2 hours each from September 4 to December 4, 2018, adding up to total 8 sessions. The program was carried out on the experimental group, whereas it was not applied to the control group, who maintained their ordinary life. Both groups were to fill out the pretest, midtest, posttest and follow-up test surveys. We explained the purpose and content of research as well as the schedule to the two groups, and received consent for the tests and the program. The follow-up test was conducted 12 weeks after the program ended.

Forest therapy program

Each session of the program was carried out by forest therapy experts such as forest therapists and forest interpreters and assistants comprised of graduate students. The program went on for 2 hours each - warmup exercises were done for 15 minutes before and after the program to prevent injuries, and the main program for 1 hour and 30 minutes. As shown in Table 1, the purpose of the program was to pursue emotional stability, activate the body, and relieve stress with cognitive and physical activities such as breathing in the forest, tree climbing, aroma massage, etc.

Testing tools

Academic stress (Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey)

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS) is a measure reconstructed for students based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey (MBI-GS), and it is comprised of three subfactors such as exhaustion, cynicism, and efficacy (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Schaufeli et al. (2002), which validated the MBI-SS, conducted a factor analysis on 1,661 college students in the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain, and proved that this model was suitable for the three countries. As a result of conducting an exploratory factor analysis by testing reliability and validity of the model on 382 college students in Korea, it was found that total 14 items (five items on exhaustion, five items on inefficacy, and four items on cynicism) were suitable. After confirming the suitability of the factor structure model, it was proved to be suitable in the three-factor model (Lee and Lee, 2013). This study uses the questionnaire by Shin et al. (2011) who adapted the MBI-SS and validated it for 947 students to prove that it is applicable to Korean students. The questionnaire is comprised of 15 items (five items on exhaustion, six items on inefficacy, four items on cynicism). Among the subfactors, inefficacy was calculated through reverse scoring. The responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale: ‘Strongly disagree (1 point), ‘Disagree’ (2 points), ‘Neutral’ (3 points), ‘Agree’ (4 points), and ‘Strongly agree’ (5 points).

Job-seeking stress (Job-Seeking Stress Survey)

The ‘Job-Seeking Stress Survey’ was developed by Hwang (1998) based on the Cornell Medical Index (CMI) of Cornell University, comprised of four factors (stress from studies stress from personality, stress from college circumstances, stress from family circumstances), and 72 items. This study used Hwang’s questionnaire revised and improved by Kang (2006). The questionnaire is comprised of six items on ‘stress from personality’, five items on ‘stress from family circumstances’, four items on ‘stress from studies’, four items on ‘stress from college circumstances’, and three items on ‘stress from employment anxiety’. Reliability of each factor is as follows: Cronbach’s α = .849 for stress from personality, Cronbach’s α = .876 for stress from family circumstances, Cronbach’s α = .798 for stress from studies, Cronbach’s α = .789 for stress from college circumstances, and Cronbach’s α = .782 for stress from employment anxiety, thereby showing reliability of the test. The responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale: ‘Strongly disagree (1 point), ‘Disagree’ (2 points), ‘Neutral’ (3 points), ‘Agree’ (4 points), and ‘Strongly agree’ (5 points).

Data analysis

Statistical treatment and analysis of data were conducted using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Science) 21.0 program. Frequency analysis was conducted to analyze the demographic characteristics. An independent samples t-test was conducted to test the homogeneity between the experimental group and control group, and one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) was used to test academic and job-seeking stress. It was tested at the significance level of p < .05, p < .001.

Results and Discussion

General characteristics of subjects

For general characteristics, this study examined gender, age, year of college, grade point average (GPA) of the entire semester, GPA satisfaction and family economic status, and conducted a frequency analysis (Table 2). There were 39 male (65%) and 21 female (35%) subjects, indicating that more male students participated than female. Most of the subjects were aged 20 (25%), 21 (23.33%) and 22 (16.67%), and the average age was 21.5 (±1.74). For GPA, 23 subjects received ‘3.5 to lower than 4.0’ (38.33%), 17 received ‘3.0 to lower than 3.5’ (28.33%), 13 received ‘2.0 to lower than 3.0’ (21.67%), six received ‘4.0 or higher’ (10.00%), and one received ‘1.0 to lower than 2.0’ (1.67%). As for GPA satisfaction, 27 subjects were ‘dissatisfied’ (45.00%), 17 were ‘neutral’ (28.33%), nine were ‘satisfied’ (15%), and seven were ‘very dissatisfied’ (11.67%). While many subjects showed medium-high GPA, many showed medium-low satisfaction. For family economic status, 31 subjects were ‘middle’ (51.67%), 16 were ‘medium-high’ (26.67%), eight were ‘medium-low’ (13.33%), three were ‘high’ (5.0%), and two were ‘low’ (3.33%).

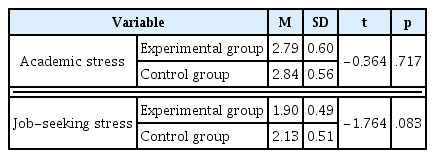

Test for homogeneity of academic and job-seeking stress between groups

To test the homogeneity between groups, an independent samples t-test was conducted on academic stress and job-seeking stress in the pretest. As shown in Table 3, the two groups did not show a statistically significant difference in academic stress (t = −0.364, p = .717). There was also no statistically significant difference in job-seeking stress (t = −1.764, p = .083), thereby confirming that the experimental group and control group are homogeneous.

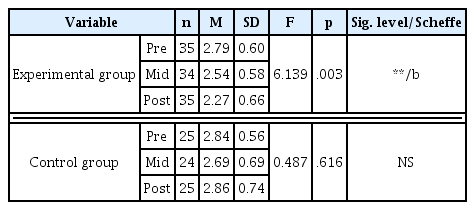

Verifying the effects of the forest therapy program on academic stress

Table 4 shows the results of conducting ANOVA among the pretest, midtest, and posttest to determine the effects of the forest therapy program on academic stress. The experimental group that participated in the forest therapy program showed a significant difference between the pretest (M = 2.79, SD = 0.60) and posttest (M = 2.27, SD = 0.66; F = 6.139, p = .003). Accordingly, the academic stress of the experimental group decreased after the program, which indicates that the program has the effect of reducing academic stress. This result is consistent with Ulrich et al. (1991) claiming that the natural environment reduces stress. The control group did not show a significant difference in the academic stress scores among the pretest (M = 2.84, SD = 0.56), midtest (M = 2.69, SD = 0.69), and posttest (M = 2.86, SD = 0.74; F = 0.487, p = .616).

Table 5 shows the results of analyzing the subfactors of academic stress. In the experimental group, exhaustion (F = 1.914, p = .153) did not show a significant change within the course of the program, but it decreased as the program went on from pretest (M = 2.77, SD = 0.99) to posttest (M = 2.39, SD = 0.82). Cynicism (F = 4.263, p = .017) and inefficacy (F = 6.776, p = .002) showed a significant decrease as the program went on. This represents that the forest therapy program has the effect of recovering cynicism and inefficacy. The control group did not show a significant change in all three factors such as exhaustion (F = 0.516, p = .599), cynicism (F =0.399, p = .672), and inefficacy (F = 0.209, p = .812).

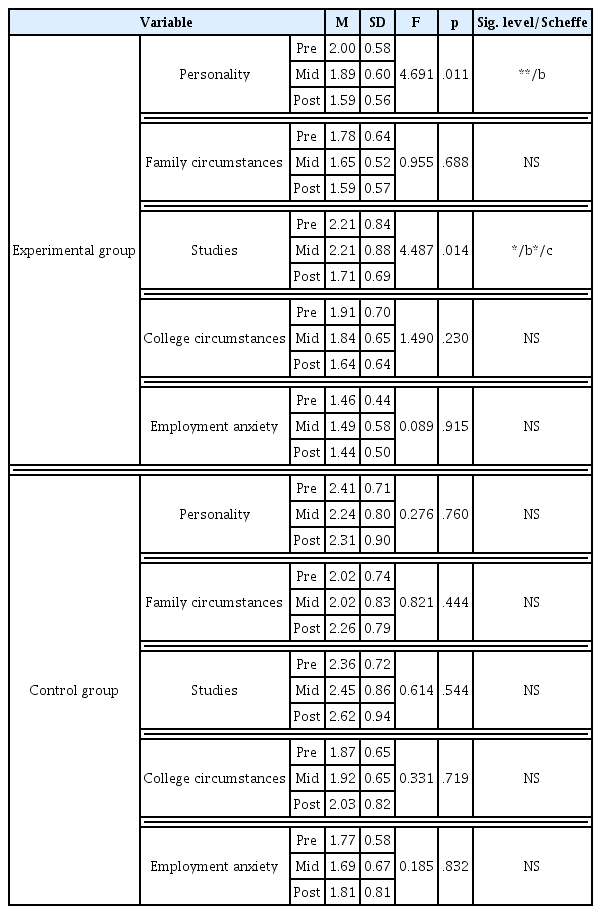

Verifying the effects of the forest therapy program on job-seeking stress

Table 6 shows the results of conducting ANOVA among the pretest, midtest, and posttest to determine the effects of the forest therapy program on job-seeking stress. In the experimental group, job-seeking stress continuously decreased after the pretest (M = 1.90, SD = 0.49), showing a significant decrease in the posttest (M = 1.60, SD = 0.48; F = 3.626, p = .03). This indicates that the program has the effect of reducing job-seeking stress. This is consistent with the study by Kim et al. (2014) proving that forest activities reduce stress. The control group did not show a significant difference between the pretest and posttest (F = 0.365, p = .695).

Table 7 shows the results of analyzing the subfactors of job-seeking stress. In the experimental group, personality (F = 4.691, p = .011) and studies (F = 4.487, p = .014) showed a significant decrease in the posttest than the pretest. For family circumstances (F = 0.955, p = .688), college circumstances (F = 1.490, p = .230), and employment anxiety (F = 0.089, p = .915), the means in the posttest decreased compared to the pretest. This indicates that the experimental group that received forest therapy showed a decrease in job-seeking stress, whereas the control group that did not receive therapy did not show a decrease in job-seeking stress, which shows that the forest therapy program helps reduce job-seeking stress. In the control group, all subfactors such as personality (F = 0.276, p = .760), family circumstances (F = 0.821, p = .444), studies (F = 0.614, p = .544), college circumstances (F = 0.331, p = .719), and employment anxiety (F = 0.185, p = .832) did not show a significant difference in the pretest and posttest.

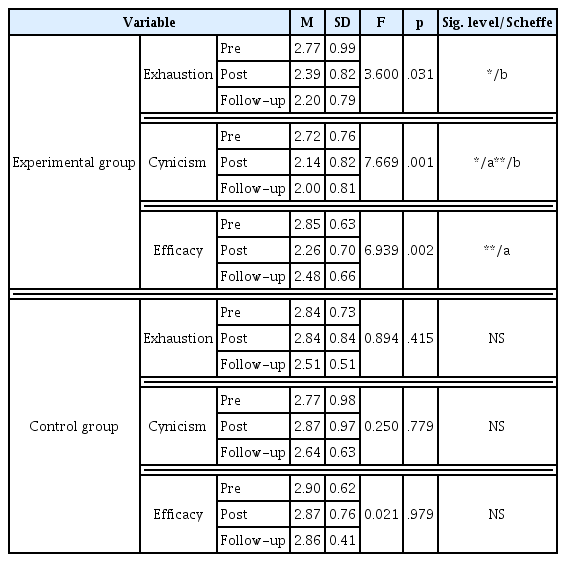

Verifying the persistence of the forest therapy program’s effect on academic stress

A follow-up test was conducted after 12 weeks to test the persistence of the forest therapy program’s effect on academic stress. The test results are as shown in Table 8. Six subjects in the experimental group and 14 in the control group dropped out, and thus 29 subjects in the experimental group and 11 in the control group participated in the follow-up test. For the ANOVA test (F = 8.062, p = .001) of the experimental group, there was a significant result in which the academic stress decreased in the follow-up test (M = 2.26, SD = 0.59) compared to the pretest (M = 2.79, SD = 0.60), whereas there was no significant difference between the posttest (M = 2.27, SD = 0.66) and the follow-up test, and academic stress was sustained. For the ANOVA test (F = 0.326, p = .723) of the control group, there was no significant result among the pretest (M = 2.84, SD = 0.56), posttest (M = 2.86, SD = 0.74), and follow-up test (M = 2.69, SD = 0.40).

The results of the ANOVA test of each subfactor of academic stress are as shown in Table 9. In the experimental group, exhaustion (F = 3.600, p = .031) decreased significantly in the follow-up test (M = 2.20, SD = 0.79) compared to the pretest (M = 2.77, SD = 0.99). Cynicism (F = 7.669, p = .001) decreased significantly in the posttest (M = 2.14, SD = 0.82) and follow-up test (M = 2.00, SD = 0.81) compared to the pretest (M = 2.72, SD = 0.76). Inefficacy (F = 6.939, p = .002) did not show a significant difference between the pretest (M = 2.85, SD = 0.63) and follow-up test (M = 2.48, SD = 0.66), but the mean decreased. All three subfactors did not show a significant difference between the posttest and follow-up test, which shows that stress, which had de creased in the posttest, remained the same without increasing in the follow-up test. Moreover, exhaustion and cynicism showed a significant reduction effect between the pretest and follow-up test, indicating that the stress reduction effect of the forest therapy program was sustained. The results of the ANOVA test of each subfactor of academic stress in the control group did not show a significant difference in all three subfactors such as exhaustion (F = 0.894, p = .415), cynicism (F = 0.250, p = .779), and inefficacy (F = 0.021, p = .979).

Verifying the persistence of the forest therapy program’s effect on job-seeking stress

A follow-up test was conducted after 12 weeks to test the persistence of the forest therapy program’s effect on job-seeking stress. The test results are as shown in Table 10. For the ANOVA test (F = 3.591, p = .031) of the experimental group, there was no significant difference between the pretest (M = 1.90, SD = 0.49) and follow-up test (M = 1.67, SD = 0.47) even though the mean decreased. There was also no significant difference between the posttest (M = 1.60, SD = 0.48) and follow-up test, and job-seeking stress was sustained. As for the ANOVA test (F = 0.235, p = .791) of the control group, there was no significant result among the pretest (M = 2.13, SD = 0.51), posttest (M = 2.24, SD = 0.71), and follow-up test (M = 2.19, SD = 0.40).

The experimental group showed a reduction effect in job-seeking stress between the pretest and posttest, and the effect was sustained since there was no significant increase in the follow-up test compared to the posttest.

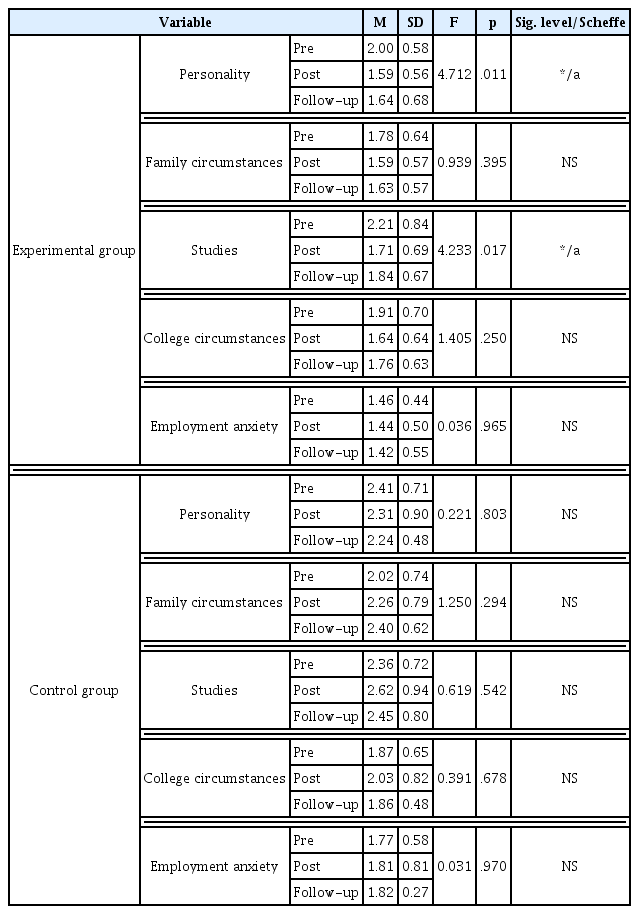

The results of the ANOVA test of each subfactor of job-seeking stress are as shown in Table 11. In the experimental group, personality (F = 4.712, p = .011) decreased significantly in the posttest (M = 1.59, SD = 0.56) and follow-up test (M = 1.64, SD = 0.68) compared to the pretest (M = 2.20, SD = 0.58), whereas there was no significant difference between the posttest and follow-up test. Studies (F = 4.233, p = .017) decreased significantly in the posttest (M = 1.71, SD = 0.69) compared to the pretest (M = 2.21, SD = 0.84), and also decreased in the follow-up test (M = 1.84, SD = 0.67) but did not show a significant difference. There was no significant difference in all of family circumstances (F = 0.939, p = .395), college circumstances (F = 1.405, p = .250), and employment anxiety (F = 0.036, p = .965).

The results of the ANOVA test of each subfactor of job-seeking stress in the control group did not show a significant difference in all five subfactors such as personality (F = 0.221, p = .803), family circumstances (F = 1.250, p = .294), studies (F = 0.619, p = .542), college circumstances (F = 0.391, p = .678), and employment anxiety (F = 0.031, p = .970).

Conclusion

This study was conducted to properly reduce stress of college students and improve the quality of their lives by determining the effects of the forest therapy program on academic and job-seeking stress. The program, comprised of forest walking, forest bathing, playing with natural objects and tree climbing, was carried out by forest therapy experts such as forest therapists and interpreters. The program began with total 60 subjects (35 in the experimental group and 25 in the control group). 20 of them dropped out before the follow-up test, and thus 40 subjects (29 in the experimental group and 11 in the control group) participated in the follow-up test. The experimental group participated in eight sessions of the forest therapy program lead by forest therapy experts to determine the stress reduction effect. The results were tested using the academic and job-seeking stress surveys.

The results of this study are as follows. First, the forest therapy program was effective in reducing academic stress. The experimental group that participated in the program (F = 6.139, p = .003) showed a statistically significant reduction effect in academic stress between the pretest and posttest. There was no statistical significance between the pretest and midtest, which may be due to the insufficient time and sessions to display the effect of the program. The control group (F = 0.487, p = .616) did not show a statistically significant difference.

Second, as a result of verifying the job-seeking stress reduction effect, the experimental group (F = 3.626, p = .030) showed a statistically significant difference between the pretest and posttest, showing the reduction effect of the forest therapy program on job-seeking stress. There was no statistical significance between the pretest and midtest, implying that there is insufficient time and number of sessions like academic stress. The control group (F = 0.365, p = .695) did not show a statistically significant difference.

Third, as a result of verifying the persistence of the forest therapy program’s academic stress reduction effect, the experimental group (F = 8.062, p = .001) showed a statistically significant difference, and the control group (F = 0.326, p = .723) did not. The experimental group showed a statistically significant difference between the pretest and follow-up test, but no statistically significant change between the posttest and follow-up test. This indicates that academic stress, which decreased after the program, continued to remain low instead of increasing after the program, showing that the program has persistence in its academic stress reduction effect.

Fourth, as a result of verifying the persistence of the forest therapy program’s job-seeking stress reduction effect, the experimental group (F = 3.591, p = .031) showed a statistically significant difference, and the control group (F = 0.235, p = .791) did not. The experimental group showed the job-seeking stress reduction effect between the pretest and posttest, but no significant difference between the posttest and follow-up test. This shows that the result of the follow-up test was not significantly lower than that of the pretest, but job-seeking stress that decreased from the pretest to the posttest did not show a significant difference between the posttest and the follow-up test but showed persistence instead. This proved that the job-seeking stress reduction effect of the forest therapy program has persistence.

This study proved the effects of the forest therapy program on academic and job-seeking stress based on the results above. Moreover, persistence of the effects was proved to verify that the stress reduction effect remains even after the program has ended. This result is consistent with the stress recovery theory (SRT) by Ulrich et al. (1991) that shows the stress reduction effect of nature. Furthermore, it is in line with previous research proving the job-seeking stress reduction effect in the pretest and posttest after carrying out 8 sessions of the forest therapy program for approximately 2 months with 70 subjects (Lee, 2015). It is also consistent with previous research proving the academic stress reduction effect in the pretest and posttest after carrying out 12 sessions of the forest therapy program for approximately 2 months with 20 elementary school students (Jeong, 2018). Accordingly, this study examined and confirmed the persistence of the forest therapy program that has not been covered in previous studies.

This study verified the stress reduction effect of the forest therapy program on college students using the forest on campus and proved the persistence of the effect. This study has significance in that it has verified that the program using the forest on campus, which is highly accessible for college students, can reduce stress of most college students, and that the stress reduction effect has persistence. However, there are limitations in that the results of this study cannot be generalized since the subjects are limited to students of a single college. It is necessary to consider the regional and environmental differences in studying college students. Furthermore, the site is somewhat monotonous for the forest therapy program. Even though there is a mix of broadleaf and needleleaf trees, there are only a few of them and most are Chamaecyparis pisifera (Siebold & Zucc.) Endl. Finally, many subjects dropped out in the follow-up test to verify the persistence, thereby deteriorating the reliability of the statistics. Further research must take dropouts into consideration when deciding on the number of subjects, and manage them in order to prevent dropouts. These limitations will be hopefully overcome by future studies in experimental design.