Factors Affecting the Willingness to Pay for Environmental Improvements during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Taean-gun, Chungcheongnam-do

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

This study aimed to assess satisfaction with environmental factors during the COVID-19 pandemic and key factors affecting the willingness to pay (WTP) for environmental improvements using logistic regression analysis.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey data of 504 residents of Taean-gun in Chungcheongnam-do (South Chungcheong Province), taken from July to August 2020, were used.

Results

The assessment of their satisfaction with five environmental factors found that their satisfaction with the natural ecology had the highest score, while their satisfaction with the waste factor had the lowest score. With respect to overall environmental satisfaction, it was found that regardless of gender, age, and income, most residents were highly satisfied with the overall environment of Taean-gun (Taean County). In addition, the WTP for environmental improvements was slightly higher among males than among females. Residents in their 60s or older and with a monthly income of 4–4.99 million won were most likely to express WTP for environmental improvements. A binominal logit analysis found that increased environmental concerns (EC), satisfaction with environmental health (EHS) and income were crucial factors in determining the WTP for environmental health. The variables of increased EC and income, have a positive (+) relationship with WTP, while the variable of EHS has a significantly a negative (−) relationship with WTP.

Conclusion

In other words, the higher the EC, the lower the EHS, and the higher the income, the more likely residents were to express WTP for environmental improvements. This study has significance in that it can provide primary data for sustainable local environmental plans to improve public environmental awareness for sustainability, and environmental strategies to prepare for post-pandemic life.

Introduction

“Failure to respond to climate change”, “extreme weather events”, “biodiversity loss”, “natural resource crises” and “human environmental degradation” are five of the top 10 risk factors the world faces in the next decade according to the Global Risk Report 2022 published by the World Economic Forum in 2021 (McLennan, 2022). As the environmental sector ranks in the top 5, accounting for half, it appears that the importance of the environment increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the recent Global Risk Report 2024, extreme weather events are identified as the greatest threat facing humanity in 2024, and the major risk factors the world faces in the next decade are related to the acceleration of climate change and the failure to respond to climate change, including extreme weather events, rapid changes in the earth’s ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, and scarcity of natural resources (McLennan, 2024). As the long-term risk factors humanity faces are closely related to the environment, it can be expected that the public role of the central and local governments in improving environmental quality. In combating climate crisis, environmental policies will be further emphasized in the future.

In 2020, the unprecedented global infectious disease outbreak, COVID-19, went beyond threatening individual health to have a huge impact on society as a whole, with social order and economic crises emerging (Borio, 2020; Susskind and Vines, 2020). Multiple studies have been conducted on the cause and spread of COVID-19. Notably, from an environmental perspective, some studies have suggested that meteorological factors, including temperature, humidity, and precipitation, affect the transmission of COVID-19; others report that the rate of COVID-19 transmission varies depending on air quality, various pollutants, and water and soil characteristics (Han et al., 2023; Cheval et al., 2020; SanJuan-Reyes et al., 2021; Annlet et al., 2021; Vadiati et al., 2023; Rume and Islam, 2020; El Zowalaty et al., 2020). As the relationship between infectious diseases, including COVID-19, and environmental sectors is being studied, and more environmental research is needed for a sustainable society, it is time for central and local governments to pursue environmental measures and policies from a long-term perspective to improve the environment.

Satisfaction with the environment varies from region to region depending on geopolitical characteristics. Satisfaction in each environmental sector may vary depending on a number of externalities, including differences in individual subjective tendencies and ecosystem service benefits for each region, as well as the occurrence of various pollutants. Reviewing the existing research, as quality of life and environmental satisfaction are related, many studies have been conducted which examined residents’ environmental satisfaction (Ma et al., 2018; Lee, 2021, Frey, 2010; Ferreira et al., 2006). Various studies were performed in each environmental sector, including residential or life satisfaction based on air or water pollution, satisfaction with forest-related ecosystem services in the natural ecology sector, and satisfaction with management systems and improvement plans in the soil and waste sector (MacKerron and Mourato, 2009; Kruize and Ruysbroek, 2004; Wakuma, 2019; Luechinger, 2009; Kim and Kang, 2016; Frey et al., 2010; Rehdanz and Maddison, 2008; Nadeem, 2020; Shi et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Olander et al., 2018). Recently, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, studies have reported that environmental improvement and health should be prioritized (Anessi-Pessina et al., 2020; Tracker, 2020; Dzigbede et al., 2020). A number of other studies have suggested a relationship between human health and the environment, and examined the importance of the surrounding environment and satisfaction with the residential area from a mental health perspective (Anessi-Pessina et al., 2020; Tracker, 2020; Dzigbede et al., 2020). Moreover, many studies have been conducted on approaches to improving environmental quality, including studies estimating the willingness to pay (WTP) for improved water services using the contingent valuation method (Galarza Arellano, 2023; Parsons et al., 2022; Catma and Varo, 2021), or estimating the WTP for better air quality and examining the factors affecting the public’s WTP (Malik et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2024; Song et al., 2021). However, few studies have examined satisfaction for each environmental sector in regions and WTP to pay for environmental improvements based on changes in environmental concerns after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Taean-gun (Taean County) has diverse natural and environmental resources, including areas that require habitat protection. It utilizes forest and marine resources, including Taeanhaean National Park, the only coastal national park in the Chungcheongnam-do Province, the Taean Peninsula on the west coast, beaches, Chinripo Arboretum, and Anmyeondo Island Recreational Forest. On the other hand, in 2007, the Taean Crude Oil Spill occurred off the coast of Taean, resulting in severe marine pollution. As the Taean Thermal Power Plant is located in the area, there is also a high possibility of air pollution. As of January 7, 2021, during the pandemic period, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Taean-gun per 100,000 people was 54.6, which was lower than the national rate of 128.6 and the Chungcheongnam-do rate of 83.4. Although the actual prevalence of COVID-19 was low, people in Taean-gun perceived the risk both directly and indirectly, and seemed to have high environmental awareness and sensitivity to environmental health (Park, 2021). It is an area in which the direction of local government budget investment, and investment in the environmental sector are important, as it has two sides, encompassing both various environmental factors and environmental risk factors.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the satisfaction of Taean-gun residents with each environmental sector and whether their environmental concerns have changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to determine the willingness to pay for environmental improvement and the determinants that affect the willingness to pay. In this study, frequency analysis, cross-tabulation analysis, and logit analysis were performed based on a survey conducted in 2020, during the COVID-19 period. Thus, this study has significance in that it can be presented as basic data to emphasize the importance of a sustainable environment when formulating environmental policies in preparation for future pandemics, and can be used to improve residents’ awareness.

Research Methods

Study area

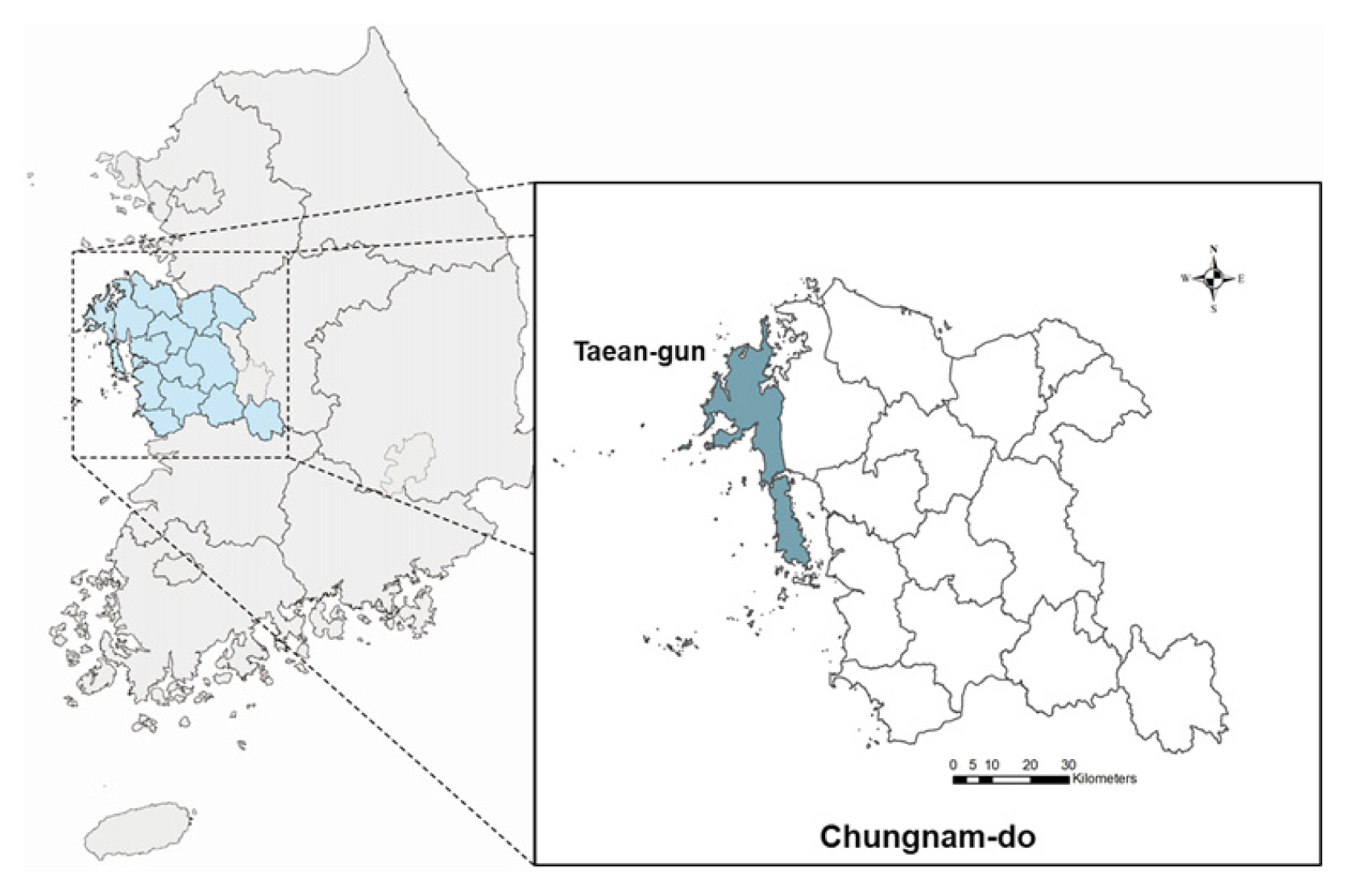

The study area was Taean-gun, Chungcheongnam-do (Fig. 1). As of 2023, the total population of Taean-gun is 60,866, with a total area of 2516.13 km2. Taean-gun is a peninsula bordered on three sides by the West Sea. The entire area is called “Taean Peninsula,” and borders the city of Seosan, in South Chungcheongnam-do, to the east. In terms of administrative districts, the area is divided into two eups (towns) and six myeons (villages). It is bordered by the city of Seosan and Cheonsuman Bay to the east, the West Sea to the west, Wonsando Island in the city of Boryeong to the south and the Deokjeok Archipelago in the city of Incheon to the north; put simply, Taean-gun is surrounded by the sea on all sides except the east, and has a 559.3 km long ria coast, with 114 islands. The topography is a low hilly area that is high in the north and low in the south; Ihwasan, Ijeoksan, Seungjusan and Cheolmasan mountains are located in the north, Jiryeongsan mountain in the west and Baekhwasan mountain in the city center, accounting for 55% of the total area. The rivers are mainly distributed in the northern part of Taean-gun, a mountainous area, and take a natural form, mainly in rural areas. The area has abundant tourism and recreational resources, with the advantage of a natural ecosystem. Meanwhile, in the summer, the higher number of tourists at resorts and tourist destinations increases water pollution and the amount of waste generated, raising concerns about habitat damage in the area. Not only is the area home to a thermal power plant and industrial complexes that emit large amounts of hazardous chemicals and air pollutants, but in 2007 a large amount of crude oil spilled into the sea off the coast, causing extensive damage to the environment of the marine basin. Thus, it is also an area in which there is a risk of direct and indirect health damage to residents (Yoo et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2020; Lee and Kim, 2021; Kang, 2021).

Method

Using a survey, between July and August 2020, one-on-one interviews were conducted with residents in eight towns and villages in Taean-gun by experienced researchers who had received prior training in surveying. The characteristics of the population were examined by extracting the ratio of respondents by gender and age, and the sample was selected by planning the survey scale. Descriptive analysis was performed using Stata software on a total of 504 valid responses only, once those with insincere responses were excluded.

The demographic survey questions consisted of general information about the respondents, including gender, age, and location of residence. The survey questions were designed based on existing studies and reports to investigate environmental conditions in Taean-gun, including current environmental satisfaction, changes in environmental concerns (EC) after COVID-19, satisfaction with environmental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, willingness to pay for environmental improvement, and socioeconomic characteristics. Satisfaction items surveyed included satisfaction with air, water, natural ecology, waste, soil, and the overall environmental factors; the questions were composed using a 5-point Likert scale which ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Data from the survey were analyzed using frequency analysis to determine satisfaction with environmental factors, willingness to pay for environmental improvements, and demographic characteristics. Resident satisfaction with each environmental factor was examined using frequency analysis to determine the mean and standard deviation of the data surveyed on a 5-point scale. Moreover, frequency analysis and cross-tabulation analysis were used to examine environmental concerns (EC), environmental health satisfaction (EHS), and WTP for environmental improvements by demographic characteristics, including gender, age, and income. A binomial logit analysis was conducted to determine which variables affect willingness to pay for environmental improvements. Binomial logit analysis is a statistical technique that uses bivariate variables as the dependent variable, and includes variables that may affect the independent variable to identify statistically significant variables. In this study, a binomial logit analysis was conducted with willingness to pay for environmental improvement as the binary dependent variable, and independent variables such as increased concerns in the environment, satisfaction with environmental health, gender, age, and income.

Results and Discussion

General characteristics of respondents

Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the Taean-gun respondents are as follows (Table 1). For gender, the proportion of males and females was almost equal, with 49.7% males and 50.1% females. For age, those in their 50s and 60s or older were the most prevalent, with each representing 25.3% of the survey group, followed by those in their 30s (19.2%) and 40s (18.8%), at similar proportions. In terms of income, those with a monthly income of 4–4.99 million won represented the largest group at 37.8%, followed by those with a monthly income of 3–3.99 million won (32.7%).

Satisfaction with environmental factors

Satisfaction based on changes in environmental concerns

The results of the survey of Taean-gun residents’ satisfaction with environmental factors are shown in Table 2. The average satisfaction of Taean-gun residents with the overall environmental factors (overall environmental satisfaction) was 3.75 points, indicating that they were generally satisfied. Among the environmental factors, the highest level of satisfaction was found to be with natural ecology at 3.76 points, followed by soil (3.44), water (3.34), air (3.17), and waste (2.29; the lowest satisfaction level). This result seems to be related to the fact that the environmental factor that they could most visually recognize was waste, and the amount of waste increased during the pandemic period due to waste associated with COVID-19 (Yoon et al., 2021). Furthermore, Taean-gun has a lot of marine debris problems caused by visitors who come to enjoy the West Sea, which is likely to affect their low satisfaction with the waste factor (Kang, 2024).

Demographic characteristics based on overall environmental satisfaction (OES)

Table 3 shows the results of the survey of Taean-gun residents’ OES. By gender, both males and females had a high percentage of respondents who said their OES was “high,” at 54.2% and 46.6%, respectively. Among all age groups, most respondents said their OES was “high.” By age group, the percentage of respondents with “high” environmental satisfaction was 50% among those in their 20s, 51.5% among those in their 30s, 50.5% among those in their 40s, 53.9% among those in their 50s, and 46.1% among those in their 60s or older. By income, 45.5% of residents with an income of 1.99 million won or less responded that they had “high” environmental satisfaction, and 44.9% of residents with an income of 2.00–2.99 million won responded that they had “high” environmental satisfaction. Among residents with incomes of 3.00–3.99 million won, 4.00–4.99 million won, and 5 million won or more, 50.9%, 51.3%, and 56.2%, respectively, responded that they had “high” environmental satisfaction. Based on this, it was found that regardless of gender, age, or income, most respondents reported high satisfaction with the overall environment in Taean-gun.

Demographic characteristics based on environmental concerns (EC) after the COVID-19 pandemic

When asked whether their EC changed after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4), by gender, 50.6% of males reported an increase in their EC, and 45.8% reported no change; among females, 48.6% reported an increase in their EC, and 47.4% reported no change. By age, the group in their 20s had the highest proportion reporting no change in their EC (50.0%), followed by those reporting an increase (48.2%). Those in their 30s and 40s had the highest percentages of respondents reporting no change in EC (49.5%) and an increase (52.6%), respectively. Those in their 50s had the highest percentage (48.4%) reporting no change in their EC, while those in their 60s or older had the highest percentage (53.9%) reporting an increase in their EC. Moreover, a slightly higher percentage of males than females responded that their EC increased after the COVID-19 pandemic. By age, more respondents in their 40s, and in their 60s and older reported an increase in their EC than other age groups. By income, more respondents with monthly incomes of 2–2.99 million won and 5 million won or more reported an increase in their EC than other income groups.

Demographic characteristics based on environmental health satisfaction (EHS)

The results of the survey of Taean-gun residents’ EHS are shown in Table 5. First, by gender, in both males and females the largest group reported being moderately satisfied with environmental health, at 41.4% and 52.2%, respectively. By age, 50.0% of those in their 20s, 50.5% of those in their 30s, 45.3% of those in both their 40s and 50s, and 45.3% of those in their 60s or older reported being moderately satisfied with environmental health. Across all age groups, from those in their 20s to those in their 60s or older, the highest percentage of respondents reported moderate satisfaction with EHS. By income, the highest percentage of respondents reported moderate satisfaction with EHS; 72.7%, 33.3%, 49.7%, 47.1%, and 45.8% for groups with monthly incomes of 1.99 million won or less, 2.0 to 2.99 million won, 3.0 to 3.99 million won, 4.0 to 4.99 million won, and 5 million won or less, respectively.

WTP for environmental improvements by socio-economic background

Table 6 shows the results of the survey on respondents’ WTP for environmental improvements according to their socio-economic background. By gender, 165 males (65.7%) were willing to pay for an improved environment and 86 (34.3%) were not; among females, 174 (68.8%) respondents were willing to pay and 79 (31.2%) were not. Looking at WTP by age group, among those in their 20s, 42 respondents (75.0%) were willing to pay, while 14 (25.0%) were not. Among those in their 30s, 65 respondents (67.0%) were willing to pay, but 32 (33.0%) were not. Of respondents in their 40s, 59 (62.1%) were willing to pay, while 36 (37.9%) were not. For respondents in their 50s, 84 (65.6%) were willing to pay, but 44 (34.4%) were not. Among respondents in their 60s or older, 89 (69.5%) were willing to pay, and 39 (30.5%) were not. Looking at WTP by income, among respondents with a monthly income of 1.99 million won or less, 17 (77.3%) were willing to pay, but 5 (22.7%) were not. Of the respondents with a monthly income of 2–2.99 million won, 52 (66.7%) were willing to pay, but 26 (33.3%) were not. Within respondents with a monthly income of 3–3.99 million won, 118 (71.5%) were willing to pay, while 47 (28.5%) were not. Of respondents with a monthly income of 4–4.99 million won, 127 (66.5%) were willing to pay, but 64 (33.5%) were not. Among respondents with a monthly income of 5 million won or more, 25 (52.1%) were willing to pay, while 23 (47.9%) were not.

WTP for environmental improvements based on environmental concerns (EC) and environmental health

Table 7 shows the results of the survey on respondents’ WTP for environmental improvements. First, looking at the WTP of respondents who reported increased EC after the COVID-19 pandemic, it was found that 115 respondents (69.7%) whose EC increased greatly had the highest percentage of WTP, followed by 41 respondents (24.8%) whose EC did not change. In addition, 66 respondents (44.0%) whose environmental health satisfaction (EHS) was moderate had the highest percentage of WTP, followed by 58 (35.2%) whose EHS had decreased. This is consistent with basic research suggesting that the lower the level of previous EHS, the higher the WTP for environmental improvements (Chu, 2020; Khan et al., 2020). Moreover, since this finding reflected EHS during the COVID-19 period, the psychological factors that seem to be at work are different from those in previous times without the health risk. This finding was in line with earlier research, which reported that environmental concern and awareness require efforts to improve environmental factors (Rousseau and Deschacht, 2020; Severo, 2021; Barouki, 2021; Rume and Islam, 2020; Vanapalli et al., 2021; Cheval et al., 2020).

WTP for environment improvement by environmental concerns and the satisfaction of environmental health

Logit analysis results

Table 8 shows the results of examining the factors affecting WTP for environmental improvements based on a binomial logit model. When examining the model fit, the log likelihood and chi-square values were found to be statistically significant at −298.93 and 39.52 (p < .001), respectively. Based on a logit analysis, it was found that increased EC and EHS were statistically significant variables at 1%, and among the socioeconomic variables, income was a statistically significant variable at approximately 5%. The signs of the statistically significant variables were (+) for EC, (−) for EHS, and (+) for income, as expected. This seems to indicate that as EC increases, EHS decreases, and as income increases, the WTP for environmental improvements increases. Furthermore, the Exp(β) values were found to be 24.81 for EC, 7.25 for EHS, and 3.97 for income. Based on EC, this suggests that, holding other variables constant, a one-unit increase in EC increases the likelihood of WTP by approximately 25 times compared to no change in EC. This result is consistent with the findings of earlier studies that WTP for environmental improvements, including improvements in water quality and air pollution, is associated with EC (Wang et al., 2006; Akhtar et al., 2017, Hao et al., 2023). It is also consistent with research reporting that household income has a positive (+) relationship with WTP, as well as previous findings that the cost of environmental improvements is considered a significant variable for WTP (Akhtar et al., 2017; Casey et al., 2006; Osiolo, 2017; Liu et al., 2018).

Conclusion

As the importance of the environment has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this study, targeted residents of Taean-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, aimed to investigate their environmental satisfaction according to their demographic characteristics during the pandemic; level of environmental concern (EC) during the pandemic; environmental health satisfaction (EHS); and willingness to pay (WTP) for environmental improvements and the variables affecting WTP. In terms of the demographic characteristics of the respondents, by gender, half of the respondents were males and half were females, and by age, the majority of respondents were in their 50s and 60s. By income, those with a monthly income of 4–4.99 million won accounted for the highest proportion, followed by those with a monthly income of 3–3.99 million won. The average income of the respondents was slightly higher than the gross regional national income per capita (KRW 37,515,000) in 2020.

With respect to their satisfaction with the overall environment and each environmental factor, their satisfaction with the overall environment was generally above average. Among the environmental factors, it was found that the highest satisfaction was in the area of natural ecology, while the lowest satisfaction was in the area of waste. It might be interpreted as the regional characteristics of Taeangun. Compared to the Seoul metropolitan area, Taean-gun has rich and diverse natural elements such as the sea and mountains. Meanwhile, in contrast with other environmental factors, the waste factor, which can be exacerbated by tourists visiting beaches, can cause immediate discomfort and odor, so the satisfaction with this factor seems to be relatively low. Moreover, since the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 period, satisfaction with the waste sector seems to have decreased due to more frequent eating at home rather than eating out under social distancing.

Regarding WTP based on socio-economic background, by gender, the proportion of males was slightly higher than that of females, and by age, respondents in their 60s or older with a monthly income of 4 to 4.99 million won were present in the highest proportion. Regarding WTP response, those with increased EC were the most likely to say they would be willing to pay and respondents with no change in EHS or low EHS were most likely to report their WTP. In addition, a binomial logit analysis was used to examine residents’ WTP for environmental improvements and the factors affecting their WTP. It was found that the higher the EC, the lower the EHS, and the higher the income, the more likely residents were to express WTP for environmental improvements.

The implications of this study are as follows. First, publicity and education among residents are needed to increase EC. At the same time, policies that can improve the quality of environmental health services are required. Budget investments for environmental policies should be expanded as considered regional characteristics and residents’ income. As EC increases due to the COVID-19 pandemic, policies for each environmental sector are needed to improve environmental quality. Second, to prepare for and mitigate the impact of future outbreaks of infectious diseases such as COVID-19, it is necessary to prioritize environmental improvement and environmental health in the direction of central and local government budget investments. For the purpose of improving the quality of environmental health services, it seems to be important to ensure basic service facilities related to policies that can reduce exposure to local infections, as well as environmental health. Third, practical strategies and support are needed for each area to implement environmental improvements.

This study has significance in that it can provide baseline data for future post-pandemic environmental plans and strategies by examining residents’ satisfaction in each environmental sector during the COVID-19 period and their WTP for environmental improvements. However, it has limitations in that the study area was restricted to Taeangun, the sample size cannot be representative of the South Korean population in terms of research method, and only basic satisfaction with environmental factors was examined. Furthermore, as this study was conducted during the COVID-19 period, future research needs to comparatively examine how environmental satisfaction has changed since the pandemic, and how satisfaction and improvements in environmental health have changed. Next research is expected to examine how environmental perceptions, which have been changed by the pandemic, lead changes into eco-friendly behaviors by applying the theory of planned behavior. In addition, with respect to estimating WTP for environmental improvements, it seems necessary to derive results using contingent valuation or choice experiment, which is a non-market valuation approach, to determine the extent of WTP. Future research on WTP for environmental improvements is also expected based on risk tolerance and regulatory focus.