Analysis of Perceived Restorativeness, Restoration Outcomes, and Plant Preference of Garden Visitors: Focusing on National Gardens, Local Gardens, and Private Gardens

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

This study was conducted to provide basic data for more active use of gardens by analyzing perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference of garden visitors.

Methods

The study was conducted from April 20 to June 25, 2022 on 6 research sites including national gardens, local gardens, and private gardens, and a survey was conducted on 360 adults who agreed to participate in the study. Perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference of garden visitors were measured. Frequency analysis, one-way ANOVA, chi-square test, Pearson’s correlation analysis, and simple linear regression analysis were conducted for data analysis using the SPSS Statistics 19.0.

Results

The results of this study are as follows. Perceived restorativeness (F = 4.507, p < .05) and restoration outcomes (F = 3.321, p < .05) of garden visitors showed statistically significant differences by group. Preference for plants with a lot of fragrance (F = 4.125, p < .05) and large-flowered plants (F = 3.155, p < .05) showed statistically significant differences by group, and the preference was high. Perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference mostly showed significant positive correlations. Perceived restorativeness had a positive effect on restoration outcomes and plant preference, and restoration outcomes had a positive effect on plant preference.

Conclusion

Gardens can serve as a restorative environment providing visitors with relaxation and psychological stability. It is necessary to reflect the design elements of a healing environment that lead to positive restorative effects on garden design and to plant preferred plants in the gardens.

Introduction

More than 55% of the world’s population is living in urban areas, and this is expected to increase to 68% by 2050. Due to continuous urbanization, non-communicable diseases are worsened in cities due to lack of green space, pollution such as noise, water and soil, urban heat islands, and insufficient active living space; and urbanization is also related to high rates of depression and anxiety as well as mental illnesses (WHO, 2022; Lederbogen et al., 2011). The rate of perceived stress by adults in South Korea in daily life was 28.7%, and 11.3% claimed they have experienced depression in which they feel sad or hopeless to the point where their everyday lives are disrupted (Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2022). This suggests that stress and depression are constantly occurring in daily life. Long-term stress, chronic anxiety, low self-esteem, and social isolation all have harmful effects on mental and physical health (Segerstrom et al., 2004). Thus, existing treatments for mental health problems must be supplemented with everyday interventions like exposure to a restorative environment (Beute and De Kort, 2018). Since Ulrich (1984) reported that looking at green natural landscape has a positive effect on the recovery of patients after surgery, many studies are proving that natural landscape is effective for stress relief and psychological stability (Grahn and Stigsdotter, 2003; Velarde et al., 2007). The need for urban green space is increasing due to the deterioration of the urban living environment, and there is also a growing social interest in the positive effects of gardens and gardening, such as improving the living environment, providing education, and promoting emotional development (Korean Association of Botanical Garden and Aboreta, 2013). Along with the increasing public interest and social awareness about gardening, the therapeutic effects and usefulness of gardens are also emphasized as the key strategy for green welfare and green healing (Park et al., 2022).

To systematically support gardens, Korea Forest Service proposed an amendment to the Arboretum Act in 2014 and established the legal grounds by amending the Act on the Creation and Furtherance of Arboretums and Gardens in 2015. The Act on the Creation and Furtherance of Arboretums and Gardens defines a garden as ‘any space in which plants, soil and stones, facilities (including artworks) etc. are continuously managed by displaying, placing, cultivating, or tending them’, and classifies gardens according to the nature of the entity that creates and manages them into national gardens created and managed by the State, local gardens created and managed by a local government, private gardens created and managed by a corporation, an organization, or a private individual, and community gardens created and managed jointly by the State or a local government and a corporation or an organization formed by residents in a village, collective housing building, or a certain area (Korea Forest Service, 2021b). By enforcing the Act on the Creation and Furtherance of Arboretums and Gardens, the First Master Plan for Promotion of Arboretums and Gardens was established and the Second Master Plan for Promotion of Arboretums and Gardens was announced; and social demand for gardens is expanding nationwide along with the operation and development of garden healing programs to classify the gardens and promote national health through gardens (Korea Forest Service, 2021a).

Gardens historically started out as part of the private realm and have become part of the public realm today for interaction between nature and people, and they are expanding into spaces to share emotional communication and bonds with local residents. As the scope of gardens has expanded into the public realm, user behavior in gardens has become more extensive, which also expanded the meaning of garden design into a space that expresses the designer’s view of art or values (Kil, 2015). There has also been active empirical research proving the psychological and physiological effects of gardens on humans (Roe et al., 2013; Lee, 2017).

Kaplan and Kaplan (1989), who proposed the attention restoration theory (ART), defined the restorative environment as an environment in which an individual’s used-up directed attention can be effectively restored and explained that the natural environment is effective in restoration setting as it has the key elements for restoration. Hartig et al. (2003) compared attention restoration and stress recovery in urban and natural environments, and Shin et al. (2013) identified a positive correlation between preference for the natural environment and psychological restoration experience. These studies reveal that mental fatigue of humans is quickly recovered in the natural environment and propose the relevance between restoration experience and perceived restorativeness in the natural environment (Urich et al., 1991; Berto, 2005).

The main components of gardens such as flowers and trees contribute to improving the public environment by providing psychological satisfaction and emotional stability through sensory experience, increasing comfort, and improving the quality of life (Kim, 2017). One of the functions of using plants in landscape design is visual therapy, which shows that visual characteristics such as form, color, and texture of plants provide a positive impression and calmness, thereby having a therapeutic effect that resolves mental stress issues (Krisantia et al., 2021). Visible landscape affects humans in various aspects including aesthetic appreciation, health, and well-being (Velarde et al., 2007), and increasing the index of greenness to see many plant leaves helps restore psychological energy and promote emotional stability (Lee, 2012). Flowers and plants with big leaves in gardens provide another sensory pleasure, and multi-sensory plants that can be found in gardens have all users immersed in a more abundant and helpful environment (Marcus and Sachs, 2013). Since 87% of the process of perceiving and remembering the external environment is carried out through vision among the five human senses, research is needed on which elements of plants can make the garden landscape more attractive. To encourage gardening of garden users that are the main subjects for making gardens popular, it is necessary to identify the usage patterns and preferences of garden users for them to easily experience and create gardens, and also to provide tips on how to create highly-preferred places and information about preferred plants (Lee et al., 2017). A survey on garden demands by Lee et al. (2017) showed that the participants are satisfied with gardening mostly because they can promote their mental health, enjoy a nature-friendly life, and make gardens beautiful, implying that gardening is an activity that that promotes mental health beyond just providing visual beauty. This suggests that gardening also has an effect on improving the quality of life.

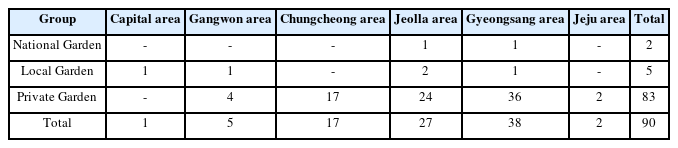

Aware of the importance of gardens, South Korea has designated Suncheon Bay National Garden and Ulsan Taehwagang National Garden as national gardens, while also registering 5 local gardens and approximately 83 private gardens (Korea Forest Service, 2022). The number of registered gardens is increasing every year due to the active use of gardens, and more and more urban residents are trying to relieve the stress from daily life based on nature, which raised the need to evaluate the restorative function of gardens as the spaces for leisure and green welfare that relieve stress and give a healthy life to urban residents. This study analyzes the relationship between perceived restorativeness and restoration outcomes according to the ART by examining visitors of national gardens, local gardens, and private gardens, and explores the relationship with plant preference through a restorative environment. This study has significance in investigating the role and value of gardens as a restorative environment by applying the ART and in providing basic data to promote use of gardens by identifying visitor characteristics. The specific research questions about garden visitors based on previous studies are as follows.

First, perceived restorativeness of visitors may vary depending on the operating entity of gardens.

Second, restoration outcome of visitors may vary depending on the operating entity of gardens.

Third, plant preference of visitors may vary depending on the operating entity of gardens.

Fourth, there may be psychological differences depending on the demographic characteristics of garden visitors.

Fifth, usage patterns of visitors may vary depending on the operating entity of gardens.

Sixth, what are the effects on key variables of perceived restorativeness, restoration outcome, and plant preference of garden visitors?

Seventh, perceived restorativeness of garden visitors will have a significant positive effect on restoration outcomes.

Eighth, perceived restorativeness of garden visitors will have a significant positive effect on plant preference.

Ninth, restoration outcomes of garden visitors will have a significant positive effect on plant preference.

Theoretical background

Perceived restorativeness

Perceived restorativeness is based on attention restoration theory (ART), which is an approach developed by Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) to understanding the restorative effects of the environment (Hartig et al, 1997). According to the ART, directed attention occurs when humans concentrate on daily life and various tasks, and this excessively used directed attention can be restored through a restoration experience or restorative environment, which also helps relieve daily fatigue and stress (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989). Kaplan (1995) classified voluntary attention and involuntary attention by James (1892) into directed attention and fascination, and saw the natural environment experience as a means that is particularly effective in recovering mental fatigue. A restorative environment, which has four components such as being away, extent, fascination, and compatibility, is an easily accessible natural environment that offers resources to relax directed attention, is attractive, and provides the immersion process of people (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan, 1995). Attention restoration is critical since attention is a core component of human efficiency, either independently or in association with other cognitive functions (Berto, 2005).

The Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) is a tool that measures the extent to which one subjectively perceives the characteristics of a certain restorative environment (Lee and Hyun, 2003). Berto (2005) used a shorter version of the PRS with five components such as being away, fascination, coherence, extent, and compatibility based on the PRS by Korpela and Hartig (1996) and revealed that, since the natural environment is fundamentally attractive, attention can be refreshed in the natural environment. Lee (2011) also examined the landscapes of cities, rooftop gardens, and forests using the PRS and proved that the restorative environment score of forests is significantly higher than that of cities.

Restoration outcome

According to Korpela et al. (2008), attention fatigue and emotional stress are alleviated by visiting or viewing the natural environment, and these positive changes are referred to as restoration outcomes. The Restoration Outcome Scale (ROS), which is used to measure the extent of recovery in a preferred place, measures the outcomes of restoration experience with relaxation, calmness, and attention restoration. Previous studies that examined the relationship between perceived restorativeness and restoration outcomes are as follows. Korpela et al. (2010) analyzed the correlation of restoration experience with preferred places and showed that restoration experience in the natural environment is more powerful than that in urban green space. Traväinen et al. (2014) compared the restorative effects of short-term visits to forests, parks, and urban environments and discovered that forests and parks were more suitable for the participants’ needs than cities in terms of perceived restorativeness, and that forests were the most attractive and harmonious place; and parks and forests turned out to be more restorative in attention restoration outcomes. Kim (2015) revealed that perceived restorativeness of Healing Forest participants has a positive effect on attention restoration outcomes, proving that perceived restorativeness in the natural environment plays an important role in restoration.

Plant preference

According to Yim (1994), environment-behavior research, which is one of environmental psychology, must be conducted based on more objective and scientific grounds as it has been led by design and planning experts in environmental design. Since visual preferences of individuals for landscape aesthetics are subjective values in applying environmental design, it is difficult to objectify them. However, it is necessary to improve the visual quality of the environment considering the visual preferences of users that many people may consider beautiful by identifying the trends in landscape preferences by user group. As part of this environment-behavior research, a survey on the usage patterns and plant preferences of visitors can be useful for setting the design direction according to visitor needs or sensitivity in using garden space, and thus can be the basic data to be used in providing guidelines and making plans. Green plants are preferred in landscapes such as savannas and forests and are considered beautiful, while flowers represent healthy and productive landscape; thus, people prefer plants that have high resource availability with big flowers and green leaves in landscape preference (Heerwagen and Orians, 1993).

There are still insufficient studies that can support the direct correlation between restoration outcomes and plant preference, but the relationship between the two can be predicted from previous studies. In a survey on garden plant preference, Kendal et al. (2012) showed that gardens are the outcomes of people’s diverse preferences as the characteristics of garden plants respond to not only the physical environment but also social heterogeneity, and that preference in garden plants is related to both visual characteristics such as flower size, leaf width, and leaf color and non-visual characteristics such as autogeny and drought tolerance. A survey on the demand for children’s gardens by Lee et al. (2007) shows that female students or lower-grade students tend to prefer plants with more fragrance or colorful and beautiful flowers, which implies that gardens must be created with plants that can satisfy the five senses. A study by Park (2016) on plant preference by personality type examined the part that is seen first in a plant among the entire tree shape, flowers, fruits, leaves, and fragrance, and the results showed that the participants paid most attention to flowers that are most visible in a plant. A study by Shin et al. (2012) on indoor plant preference by type of indoor greening showed that the participants tended to prefer foliage plants and flowers in all indoor spaces since they provide psychological stability. A study by van den Berg et al. (2003) that analyzed the relationship between environmental preference and restoration showed that higher preference for the natural environment led to greater emotional restoration. Grahn and Stigsdotter (2010) examined the preference in characteristics of urban green space and discovered that people perceive and prefer green space in 8 perceived sensory dimensions such as serene, open, natural, diverse (diverse plants and animals), sheltered, cultural, cohesive, and social. They also revealed that people perceiving stress prefer an environment characterized by the combination of shelter, nature, and species richness (diverse plants and animals), and claimed that this combination can be interpreted as the most restorative environment.

Research methods

Research sites

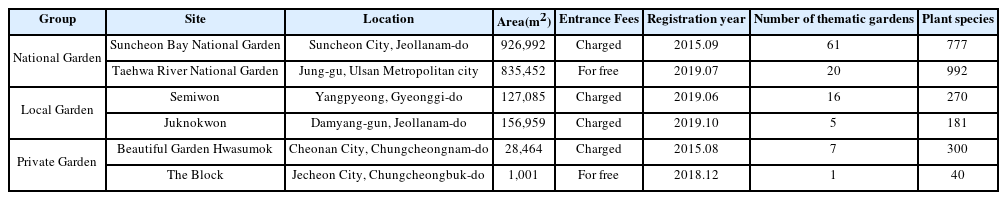

Gardens registered on Korea Forest Service as of November 2022 are 2 national gardens, 5 local gardens, and approximately 83 private gardens, with 1 in the metropolitan area, 5 in the Gangwon area, 17 in the Chungcheong area, 27 in the Jeolla area, 36 in the Gyeongsang area, and 2 in the Jeju area, and over 40 local gardens are currently being created (Table 1). As the research sites, we selected 2 national gardens such as Suncheon Bay National Garden and Taehwagang National Garden, 2 local gardens such as Semiwon and Juknokwon, and 2 private gardens such as Beautiful Garden Hwasoomok and The Block (Table 2). For selection, we investigated the number of visitors through a site survey during the preliminary survey and sent an official letter asking whether we can conduct a survey on visitors. The gardens selected were those in which the institution or the garden owner granted permission or was willing to cooperate. The other 3 local gardens were designated in 2021 and 2022, and Semiwon and Juknokwon were selected because they were both designated in 2019 and established based on the natural philosophy and environmental culture of ancestors. Since 53 out of 83 private gardens are located in the southern region and on the coast, we selected Beautiful Garden Hwasoomok and The Block as they both run a stable garden and garden café that maintains a certain number of visitors in Chungbuk and Chungnam in Chungcheong-do, the center of the national territory. Kim (2022) explains that garden cafés serve as alternative places to experience garden culture and spaces to spread garden culture to an unspecified number of visitors. There were 4 gardens with an admission fee: Suncheon Bay National Garden, Semiwon, Juknokwon, and Beautiful Garden Hwasoomok. According to a study on private gardens by Cho and Sung (2019), owners who operate gardens for free were uncomfortable about charging visitors because they think their gardens are not worth paying for. There were also gardens that also operated cafés for profit, which is the case for The Block.

Suncheon Bay National Garden covers an area of 926,992 m2, is located at 47 Gukgajeongwon 1ho-gil, Suncheon-si, Jeollanam-do, and was designated as a national garden in September 2015. This garden is created for permanent preservation of Suncheon Bay Wetland Reserve, one of the world’s 5 major coastal wetlands. There are 13 world gardens, 16 themed gardens, 32 participating gardens, 777 plant species, 5 types of 31 facilities and amenities including indoor gardens, exhibition greenhouses, and Suncheon Bay International Wetland Center. Taehwagang National Garden covers an area of 835,452 m2, is located in the whole area of Taehwa-dong, Jung-gu, Ulsan, and was designated in July 2019. This waterside naturalism garden tells the successful story of Taehwagang River, which had once been called the ‘river of death’, being revived as the ‘river of life’, and offers the experience of calmness and relaxation in the city. There are 6 themed gardens such as the ecological garden, bamboo garden, seasonal garden, aquatic garden, participating garden, and mugunghwa garden, and 992 plant species. Semiwon, a local garden, covers an area of 127,085 m2, is located at 93 Yangsu-ro, Yangseo-myeon, Yangpyeong-gun, Gyeonggi-do, and was registered in June 2019. The garden is created in the beautiful waterfront of Dumulmeori where the Namhangang River and Bukhangang River meet, based on the natural philosophy and environmental culture of ancestors. There are 16 themed gardens including White Lotus Pond, Red Lotus Pond, and Perry’s Pond, and 270 plant species. Juknokwon, a local garden, covers an area of 156,959 m2, is located in the whole area of San 37–9 Hyanggyo-ri, Damyang-eup, Damyang-gun, Jeollanam-do, and was registered in October 2019. This garden appeals to visitors with its bamboo ecological garden. There are 5 themed gardens including the historical garden, arbor garden, and traditional garden, and 181 plant species. Officially registered as the first private garden, Beautiful Garden Hwasoomok covers an area of 28,646 m2, is located at 175, Gyocheonjisan-gil, Mokcheon-eup, Dongnam-gu, Cheonan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, and was registered in August 2015. There are 5 themed gardens and various spaces including Seokbujak-gil, Tamna Botanical Garden, bonsai garden, trail and waterfall, along with diverse vegetations such as Cornus mas ‘Variegata’, Hydrangea macrophylla, Cotinus coggygria L., Zelkova serrata, and Pinus koraiensis, and idea gardens that change every season such as Allium giganteum, Lobelia inflata, and Xerochrysum bracteatum. The Block, which is the smallest private garden, covers an area of 1,001 m2 and is located at 109, Yongdu-daero 36-gil, Bongyang-eup, Jecheon-si, Chungcheongbuk-do. It is themed garden and a garden café with all kinds of vegetations including Pinus densiflora, Lonicera maackii, Ligustrum obtusifolium, and Chaenomeles sinensis as well as various garden rocks, and was registered in December 2018 (Korea Arboreta and Gardens Institute, 2022).

Research method

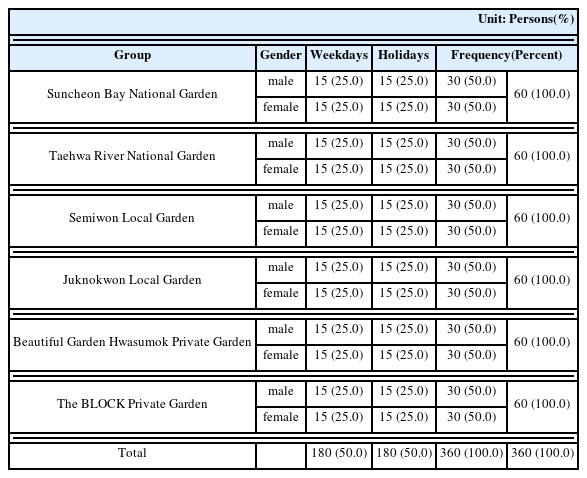

This study conducted a survey on visitors of 6 gardens: Suncheon Bay National Garden, Taehwagang National Garden, Semiwon, Juknokwon, Beautiful Garden Hwasoomok, and The Block. Purposive sampling, which is a type of non-probability sampling, was used to obtain the samples, and the survey was conducted from April 20 to June 25, 2022. The sample size in this study was determined using effect size, p-value, and power with G*Power 3. 1. 9. 7 Program (University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). The sample size of the group was calculated as 342 with reference to the study by Kang and Suh (2020) and the perception survey on gardens by Park (2021), setting the effect size as the medium effect size of 0.3 by Cohen (1988) that is commonly used in social science studies, α value of 0.05, and power of 0.95. Based on this value, the total sample size was adjusted to 376, and 360 copies of the questionnaire were ultimately analyzed excluding 16 copies with omitted responses to the survey items.

This study consists of data collection, preliminary survey, and main survey. For data collection, we collected the registration status of national gardens, local gardens, and private gardens in 2022 and the data and reports of Korea Forest Service and Korea Arboreta and Gardens Institute, and extracted variables by reviewing previous studies on the demands and preferences of garden visitors. The survey on garden visitors was divided into the preliminary survey and the main survey. The preliminary survey was conducted by collecting 30 copies of the questionnaire from garden visitors on 1 research site in April 2022, after which we tested the reliability and supplemented the questionnaire. The main survey was conducted in 6 gardens from May to June 2022 when the weather was warm and the nature was mostly green, targeting 360 subjects divided into 30 on weekdays and 30 on holidays (Table 3). When the visitors were in families or groups, we surveyed only one member within the same family or group. We conducted an exit survey 12 times on visitors exiting the garden after their visits. We provided sufficient explanation about the content and purpose of research prior to the survey, and the questionnaire was distributed to only those who agreed to participate. We set the same start time and end time for all sites, and the survey was conducted in a self-report design in which the visitors answer the survey items themselves.

Measurement tools

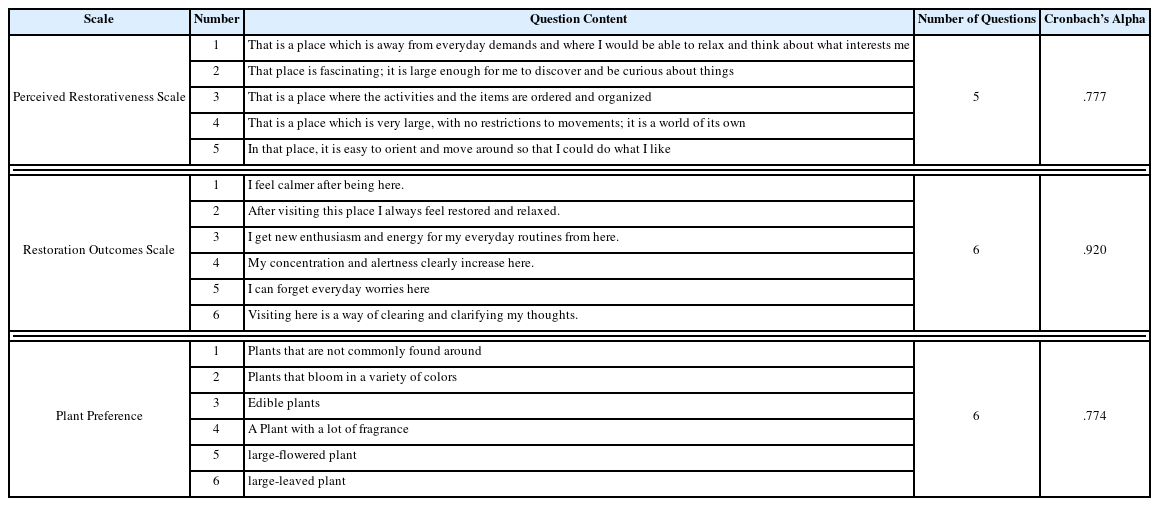

The questionnaire consisted of items on general demographic characteristics, perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference, as well as items on motivations for visit, visit frequency, companion type, means of transportation, access time, and viewing time to analyze the usage patterns of visitors. The PRS, ROS, and items on the 5-point Likert scale on plant preference as well as reliability are as shown in (Table 4).

Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS)

The Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) is a measure of how much restorativeness a certain environment has depending on the subject. Based on the PRS with 26 items by Hartig et al. (1997), a shorter version of the PRS by Kopela and Hartig (1996), and the restorative environment by Kaplan (1995), Berto (2005) created a shorter version of the PRS consisting of 5 items. We used the shorter version of the PRS adapted by Lee (2011) and used by Kim et al. (2016) in studying adults at Healing Forests. This scale consists of total 5 items, 1 each on being away, fascination, scope, coherence, and compatibility. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘Strongly disagree (1 point)’ to ‘Strongly agree (5 points)’, with higher total scores indicating higher perceived restorativeness. Cronbach’s α in this study was .777.

Restoration Outcome Scale (ROS)

For the Restoration Outcome Scale (ROS) that measures the attention restoration outcomes of subjects, we used the ROS developed by Korpela et al. (2008) and Tyrväinen et al. (2014) and adapted by Kim and Kim (2015) with factor analysis and validation completed by a study on adults. This scale consists of total 6 items on relaxation and calmness and attention restoration. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘Strongly disagree (1 point)’ to ‘Strongly agree (5 points)’, with higher total scores indicating higher restoration outcomes. Cronbach’s α in this study was .920, which is good.

Plant preference

The preference survey on plants visitors want to see when visiting the garden consisted of items developed by Lee et al. (2007) in a demand survey for plantation in children’s gardens, consisting of total 6 items such as plants that are not commonly found around, plants that bloom in a variety of colors, edible plants, plants with a lot of fragrance, large-flowered plants, and large-leaved plants. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher total scores indicating higher demand for plants. Cronbach’s α in this study was .774.

Usage patterns of garden visitors

To identify the frequency and patterns of use by garden visitors, we developed multiple-choice items on motivations for visit, visit frequency, access time, viewing time, means of transportation, and companion type.

Data analysis

For data analysis, we analyzed total 360 copies of the questionnaire using SPSS Statistics 19.0. A frequency analysis was conducted on the general characteristics of garden visitors. One-way ANOVA was conducted to test for difference in means of perceived restorativeness of garden visitors, restoration outcomes, and plant preference and test for difference in key variables according to demographic characteristics, and the Bonferroni method was used for the post-hoc test when the difference between groups was significant. A chi-square test was conducted on multiple-choice items on usage patterns of garden visitors. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted for correlation between perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference, and simple linear regression analysis was conducted for the effect of perceived restorativeness on restoration outcomes and plant preference.

Results and Discussion

General characteristics

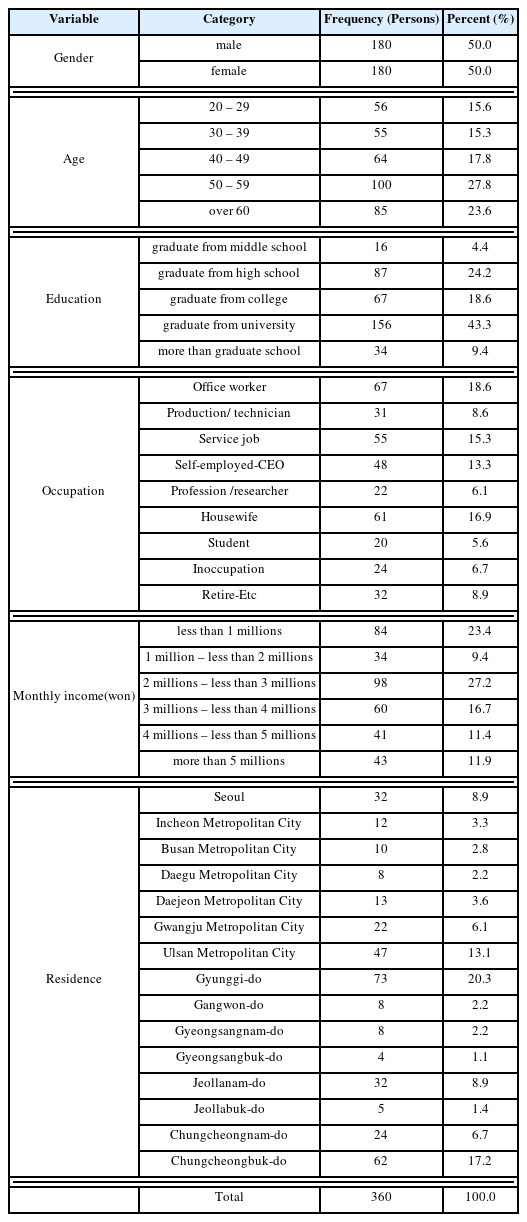

To identify the general characteristics of the participants, we conducted a frequency analysis by classifying the characteristics into gender, age, education, occupation, and average monthly income. The results of frequency analysis are as shown in (Table 5 ). There were 180 male (50 .0%) and 180 female (50.0%) participants (Table 6). 100 participants were in their 50s (27.8%), followed by 85 in their 60s or older (23.6%), 64 in their 40s (17.8%), 56 in their 20s (15.6%), and 55 in their 30s (15.3%). As for education level, 156 participants were university graduates (43.3%), followed by 87 high school graduates (24.2%), 67 junior college graduates (18.6%), 34 graduate students or higher (9.4%), and 16 middle school graduates (4.4%). For occupation, there were 67 office workers (18.6%), followed by 61 housewives (16.9%), 55 with service jobs (15.3%), 48 self-employed CEOs (13.3%), 32 retirees or others (8.9%), 31 with production and technician jobs (8.6%), 24 unemployed (6.7%), 22 professional researchers (6.1%), and 20 students (5.6%). As for average monthly income, 98 participants earned 2.01 – less than 3 million won (27.2%), 84 earned less than 1 million won (23.4%), 60 earned 3.01-less than 4 million won (16.7%), 43 earned 5.01 million won or more (11.9%), 41 earned 4.01 – less than 5 million won (11.4%), and 34 earned 1.01 – less than 2 million won (9.4%). By area of residence, 73 participants lived in Gyeonggi-do (20.3%), 62 in Chungcheongbuk-do (17.2%), 47 in Ulsan (13.1%), 32 in Seoul (8.9%), 32 in Jeollanam-do (8.9%), 24 Chungcheongnam-do (6.7%), 22 in Gwangju (6.1%), 13 in Daejeon (3.6%), 12 in Incheon (3.3%), 10 in Busan (2.8%), 8 in Daegu (2.2%), 8 in Gangwon-do (2.2%), 8 in Gyeongsangnam-do (2.2%), 5 in Jeollabuk-do (1.4%), and 4 in Gyeongsangbuk-do (1.1%).

Testing for difference between groups of garden visitors

Testing for difference in perceived restorativeness

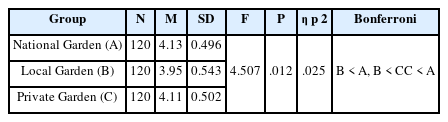

(Table 6) shows the results of conducting one-way ANOVA on 360 participants to test the difference in perceived restorativeness of national, local, and private garden visitors. Perceived restorativeness showed statistically significant differences by group at F = 4.507, p = .012,

Testing for difference in restoration outcomes

(Table 7) shows the results of conducting one-way ANOVA to test the difference in restoration outcomes of national, local, and private garden visitors. Restoration outcomes showed statistically significant differences by group at F= 3.321, p = .037,

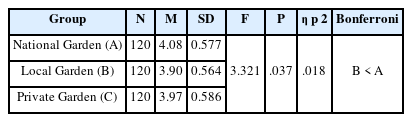

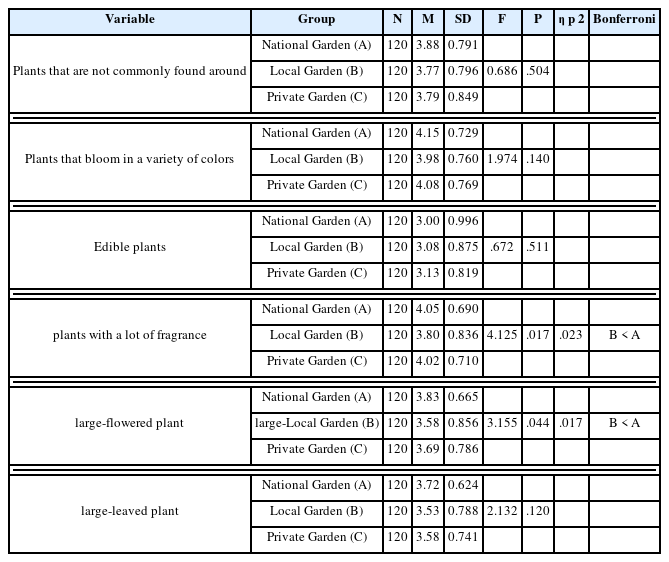

Testing for difference in plant preference

(Table 8) shows the results of conducting one-way ANOVA to test the difference in plant preference of national, local, and private garden visitors. Preference for plants with a lot of fragrance showed statistically significant differences by group at F = 4.125, p = .017,

Testing for difference according to demographic characteristics

(Table 9) shows that there were statistically significant differences as a result of analyzing the differences in perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference according to the demographic characteristics of garden visitors. There were statistically significant differences in preference for large-flowered plants according to gender and age, with the 20s showing higher preference than the 60s or older. The 30s showed higher preference for plants that bloom in a variety of colors than the 50s. The 20s and 30s showed higher preference for plants with a lot of fragrance than the 60s or older. By occupation, housewives showed higher preference for edible plants than the unemployed. By area of residence, those living in Ulsan showed higher preference for large-leaved plants than those living in Gwangju. As a result of examining the differences in perceived restorativeness according to gender, age, education, occupation, average monthly income, and area of residence, there were no statistically significant differences. There were also no statistically significant differences in restoration outcomes according to gender, age, education, occupation, average monthly income, and area of residence. There were no statistically significant differences as a result of examining the differences in preference for large-flowered plants according to education, occupation, average monthly income, and area of residence; preference for plants that bloom in a variety of colors and plants with a lot of fragrance according to gender, education, occupation, average monthly income, and area of residence; preference for edible plants according to gender, age, education, average monthly income, and area of residence; and preference for large-leaved plants according to gender, age, education, occupation, and average monthly income. These results are similar to the study results by Park (2016) that the youth show most interest in flowers from plants, by Lee et al. (2007) that younger people prefer plants with more fragrance or colorful and beautiful flowers, and by Jang et al. (2021) that firefighters in their 20s tended to show higher preference for aroma in plants than those in their 30s–50s.

Analysis on usage patterns of garden visitors

To analyze the usage patterns of garden visitors, a chi-square test (χ2 test) was conducted on multiple-choice items for motivations for visit, visit frequency, access time, viewing time, means of transportation, and companion type when visiting national gardens, local gardens, private gardens. (Table 10) shows the results of the χ 2 test to identify the motivations for visiting the gardens according to the operating entity of the garden. Motivations for visiting the gardens showed statistically significant differences by group at χ 2 (10, N = 360) = 45.828, p < .001. Specifically, 42 participants (35.0%) visited national gardens because they were close from home, 34 (28.3%) visited local gardens after being introduced by people around them, and 56 (46.7%) visited private gardens also after being introduced by people around them. The biggest motivation for visit was introduction by people around them (31.9%), followed by Internet search (23.3%), short distance from home (31.9%), group tour (9.2%), media publicity such as TV or newspaper (8.6%), and by chance (5.3%). Motivation for visit is a factor affecting visitor satisfaction and revisit, and effective tourism marketing is impossible without understanding consumer motivation (Fodness, 1994). One of the factors that have a strong impact on consumer behavior in marketing is word of mouth. A study by Kim et al. (2020) claimed that satisfaction with usage experience has a significant effect on revisit due to the effect of word of mouth, showing that visitors mostly paid visits after being introduced by people around them. These results were also consistent with the study results by Kweon et al. (2012) in a study analyzing user behavior in botanical gardens and arboretums that visitors paid visits after being introduced by people around them and for recreation.

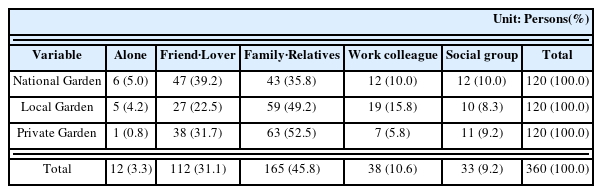

(Table 11) shows the results of the χ 2 test to identify the companion type when visiting the gardens by group. Companion type showed statistically significant differences by group at χ 2 (8, N = 360) = 18.866, p = .016. Specifically, 47 participants (39.2%) visited national gardens with friends or lovers, 59 (49.2%) visited local gardens with family or relatives, and 63 (52.5%) visited private gardens also with family or relatives. The results that many visitors were accompanied by family/relatives or friends/lovers were consistent with the results of the 2021 Korea National Tourism Survey (Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, 2022) and the study results by Kang and Suh (2020) that many visitors of Suncheon Bay National Garden visited with family.

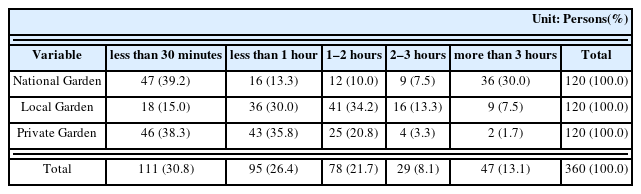

(Table 12) showed statistically significant differences in garden access time by group at χ 2 (20, N = 360) = 198.066, p < .001. Specifically, it took less than 30 minutes for 47 participants (39.2%) to visit national gardens, 1–2 hours for 41 participants (34.2%) to visit local gardens, and less than 30 minutes for 46 participants (38.3%) to visit private gardens. Most participants (57.2%) responded that it tool less than 1 hour, followed by 1–2 hours (21.7%), more than 3 hours (13.1%), and 2–3 hours (8.1%). Accessibility is the most important factor for visitors in visiting a garden and is one of the preparedness factors that cannot be ignored (Seo, 2020). These results were consistent with the study result by Grahn and Stigsdotter (2003) revealing that people with immediate access to a garden or green space are more likely to visit an urban park or a natural area in their spare time.

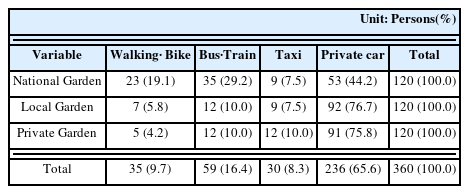

(Table 13) showed statistically significant differences in means of transportation by group at χ2 (8, N = 360) = 47.786, p < .001. Specifically, 53 participants (44.2%) visited national gardens by private car, 92 (76.7%) visited local gardens by private car, and 91 (75.8%) visited private gardens by private car. Overall, most visitors visited the gardens by private car (65.6%), followed by bus/train (16.4%), walking/bike (9.7%), and taxi (8.3%). These results were consistent with the results of the 2021 Korea National Tourism Survey (Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, 2022) that the percentage of using private cars is the highest and is annually increasing.

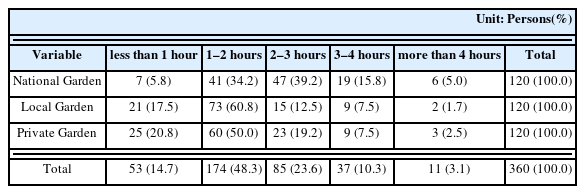

(Table 14) showed statistically significant differences in garden viewing time by group at χ2 (8, N = 360) = 46.390, p < .001. Specifically, 47 participants (39.2%) viewed national gardens for 2–3 hours, 73 (60.8%) viewed local gardens for 1–2 hours, and 60 (50.0%) viewed private gardens for 1–2 hours. Most participants viewed gardens for 1–2 hours (48.3%), followed by 2–3 hours (23.6%), less than 1 hour (14.7%), 3–4 hours (10.3%), and more than 4 hours (3.1%). These results were similar to the study results by Seo (2020) that most visitors stayed in gardens for less than 2 hours, implying the need to design gardens and develop events for visitors to stay longer, since there are various causes such as few attractions and insufficient design of traffic line.

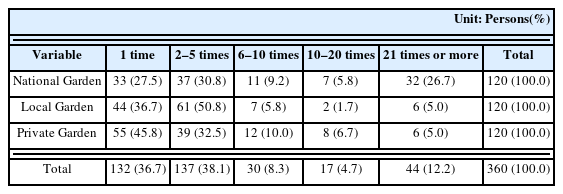

(Table 15) showed statistically significant differences in garden visit frequency by group at χ2 (8, N = 360) = 49.041, p < .001. Specifically, 37 participants (30.8%) visited national gardens 2–5 times, 61 (50.8%) visited local gardens 2–5 times, and 55 (45.8%) visited private gardens once. Most visitors visited gardens 2–5 times (38.1%), followed by once (36.7%), 21 times or more (12.2%), 6–10 times (8.3%), and 10–20 times (4.7%). According to Seo (2017), whether customers revisit a garden or not can be the result of garden evaluation and may serve as a key to indirect publicity using word of mouth or social media. This implies the need to develop highly preferred programs when providing garden information or experience to induce revisits.

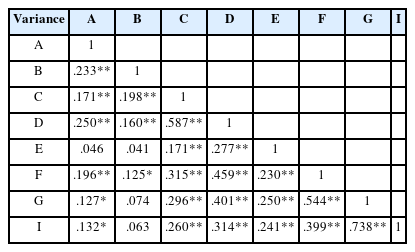

Correlation analysis of variables

(Table 16) shows the results of conducting Pearson’s correlation analysis to identify the correlation among key variables for garden visitors such as perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, plant preference, plants that are not commonly found around, plants that bloom in a variety of colors, edible plants, plants with a lot of fragrance, large-flowered plants, and large-leaved plants. The correlation between perceived restorativeness and restoration outcomes was .233, the correlation between perceived restorativeness and plants that are not commonly found around was .171, the correlation between perceived restorativeness and plants with a lot of fragrance was .196, the correlation between perceived restorativeness and large-flowered plants and was .127, and the correlation between perceived restorativeness and large-leaved plants and was .132, showing significant positive correlations. This indicates that higher perceived restorativeness leads to higher restoration outcomes. The correlation between restoration outcomes and plants that are not commonly found around was .198, the correlation between restoration outcomes and plants that bloom in a variety of colors and was .160, and the correlation between restoration outcomes and plants with a lot of fragrance was .125, showing significant positive correlations. The correlations between 6 variables of plant preference were .171–.736, showing high correlations. This indicates that higher preference for plants that are not commonly found around leads to higher preference for plants that bloom in a variety of colors. On the other hand, there were no correlations between perceived restorativeness and preference for edible plants, restoration outcomes and preference for edible plants, preference for large-flowered plants, and preference for large-leaved plants. These results were similar to the study results by Jang et al. (2014) analyzing the psychological effects of green interior office decorated with indoor plants and revealing that greater green interior effect leads to positive correlation with comfort, naturalness, and calmness. They were also similar to the study results by Kendal et al. (2012) showing that there is a weak correlation between the ratio of plants growing in people’s gardens and the preference for flowers and leaves.

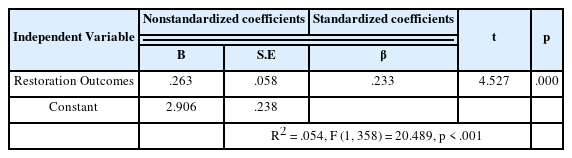

Analysis on the effect of perceived restorativeness of garden visitors on restoration outcomes

(Table 17) shows the results of simple linear regression analysis conducted to analyze the effect of perceived restorativeness of garden visitors on restoration outcomes. Since the VIF of independent variables that determine multicollinearity was less than 4.0, there was no multicollinearity. The results showed that perceived restorativeness had a significant positive effect on restoration experience (R2 = .054, F (1, 358) = 20.489, p < .001). This indicates that higher perceived restorativeness of garden visitors leads to higher restoration outcomes. These results were similar to the study results by Park and Kim (2021) that perceived restorativeness of national park visitors had a positive effect on restoration experience and life satisfaction, and by Kim and Kim (2015) that attention restoration experience through Healing Forests and healing programs had a significant effect on the emotions of healing tourism participants.

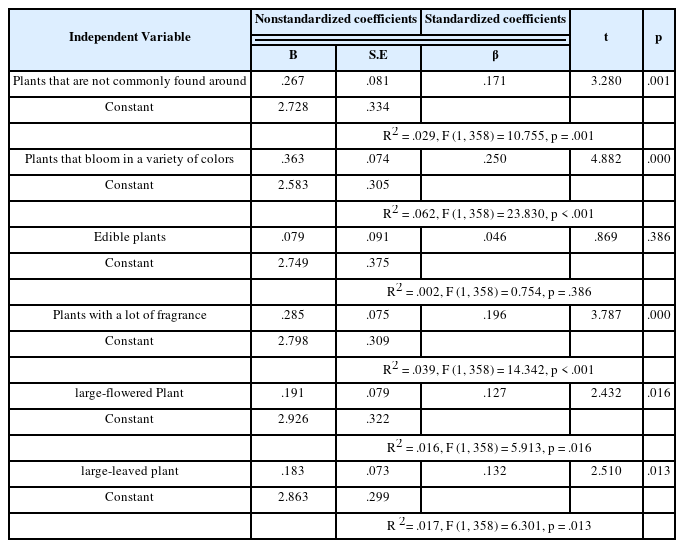

Analysis on the effect of perceived restorativeness of garden visitors on plant preference

(Table 18) shows the results of simple linear regression analysis conducted to analyze the effect of perceived restorativeness of garden visitors on plant preference. In plant preference, perceived restorativeness had a significant positive effect on preference for plants that are not commonly found around (R2 = .029, F (1, 358) = 10.755, p = .001). Perceived restorativeness had a significant positive effect on preference for plants that bloom in a variety of colors (R2 = .062, F (1, 358) = 23.830, p < .001). Perceived restorativeness had a significant positive effect on preference for plants with a lot of fragrance (R2 = .039, F (1, 358) = 14.342, p < .001). Perceived restorativeness had a significant positive effect on preference for large-flowered plants (R2 = .016, F (1, 358) = 5.913, p = .016). Perceived restorativeness had a significant positive effect on preference for large-leaved plants (R2 = .017, F (1, 358) = 6.301, p = .013). Perceived restorativeness did not have a statistically significant effect on preference for edible plants. Therefore, higher perceived restorativeness of garden visitors leads to higher preference for plants that are not commonly found around, plants that bloom in a variety of colors, plants with a lot of fragrance, large-flowered plants, and large-leaved plants. These results were similar to the study results by Jang et al. (2015) on the effect of green interior with green plants on human psychology, which revealed that space designed with green interior showed greater attention restoration effects of relaxation and refreshment than space not designed with green interior.

Analysis on the effect of restoration outcomes of garden visitors on plant preference

(Table 19) shows the results of simple linear regression analysis conducted to analyze the effect of restoration outcomes of garden visitors on plant preference. The results showed that restoration outcomes had a significant positive effect on preference for plants that are not commonly found around (R2 = .039, F (1, 358) = 14.591, p < .001). Restoration outcomes had a significant positive effect on preference for plants that bloom in a variety of colors (R2 = .026, F (1, 358) = 9.389, p = .002). Restoration outcomes had a significant positive effect on preference for plants with a lot of fragrance (R2 = .016 F (1, 358) = 5.649, p = .018). Restoration outcomes did not have a statistically significant effect on preference for edible plants, large-flowered plants, and large-leaved plants. Therefore, higher restoration outcomes of garden visitors led to higher preference for plants that are not commonly found around, plants that bloom in a variety of colors, and plants with a lot of fragrance. These results were similar to the study results by Kendal et al. (2012) that plants growing in a garden are related to people’s preference, and preference in garden plants is related to visual characteristics such as flower size, leaf width, and leaf color.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to examine the effect of perceived restorativeness on restoration outcomes and plant preference among adults who visited national gardens, local gardens, and private gardens, with the increase of gardening that is helpful for emotional restoration and stress relief. The following conclusions can be drawn based on the results of this study. Perceived restorativeness of garden visitors according to the operating entity had an effect on restoration outcomes and plant preference, and restoration outcomes had a positive effect on plant preference. These results imply that using easily accessible gardens can be a significant restoration experience and restorative environment for improving health and reducing stress of urban residents.

The results of more specific analysis of the research questions are as follows. First, there were statistically significant differences in perceived restorativeness of garden visitors according to the operating entity, and visitors experienced perceived restorativeness the most in national gardens, followed by private gardens and local gardens. Second, there were statistically significant differences in restoration outcomes of garden visitors according to the operating entity, and national garden visitors showed greater restoration outcomes than local garden visitors. These results show that national gardens have a bigger size and a greater number of plant species than local or private gardens, and thus provided more diverse restoration experiences to visitors. Thus, gardens with natural elements serve as a restorative environment that provides attention restoration, stress relief, and psychological stability. This implies that design elements of a healing environment that lead to positive restorative effects must be reflected on garden design.

Third, for plant preference of garden visitors according to the operating entity, there were significant differences in preference for plants with a lot of fragrance and large-flowered plants, and national garden visitors showed higher preference for plants with a lot of fragrance and large-flowered plants than local garden visitors. These results show that visitors prefer plants with visual characteristics such as plant shape, color, and texture in addition to a tension relief effect. Plants are important materials in a garden, and thus to promote satisfaction of garden visitors, it is necessary to consider planting plants preferred by visitors in gardens such as plants with a lot of fragrance and large-flowered plants.

Fourth, the results of analyzing the differences in perceived restorativeness, restoration outcomes, and plant preference according to the demographic characteristics of garden visitors are as follows. There were statistically significant differences in preference for large-flowered plants according to gender and age, plants that bloom in a variety of colors according to age, plants with a lot of fragrance according to age, edible plants according to age occupation, and large-leaved plants according to age area of residence. There were no significant differences in other variables. These results imply that, when creating a garden, it is possible to increase the restorative effects as well as the effects of gardening programs by using plants that bloom in a variety of colors, plants with a lot of fragrance, edible plants, and large-leaved plants according to age, occupation, and area of residence.

Fifth, the results of analyzing the visit frequency and patterns of garden visitors showed that the biggest motivation for visiting the gardens was introduction by people around them, indicating that visitor satisfaction has a strong effect on word of mouth, and thus it is necessary to improve the quality of garden publicity and services. Most visitors visited the gardens with family and relatives, which suggests the need for programs targeting families. Most visitors responded that it took less than 1 hour to access the gardens, which implies the need to increase accessible gardens in everyday life. Most visitors visited the gardens by private car, using a convenient means of transportation in terms of time and travel, which raises the need for accessible and convenient public transportation. Most visitors viewed the gardens for 1–2 hours, indicating gardens must have various traffic lines, attractions, and events. Visitors mostly visited the gardens 2–5 times, which implies the need to develop contents that provide garden information or attract visitor attention in order for the gardens to be accessible in everyday life.

Sixth, the correlation analysis between perceived restorativeness of garden visitors, restoration outcomes, and key variables of plant preference showed that higher perceived restorativeness leads to higher restoration outcomes, and higher perceived restorativeness and restoration outcomes lead to higher plant preference. This implies that planting attractive plants in the gardens may lead to attention restoration and positive emotions.

Seventh, perceived restorativeness of garden visitors had a significant positive effect on restoration outcomes. This indicates that higher perceived restorativeness of garden visitors leads to higher restoration outcomes. Attention can be restored in a highly restorative environment, and restorativeness occurs even in a short time, less than 10 minutes of exposure (Berto, 2005). Since creating a restorative environment in a garden plays an important role in restoration, it is necessary to establish facilities and layouts for visitors to feel relaxed and fascinated, and also to continuously maintain and manage those facilities.

Eighth, perceived restorativeness of garden visitors had a significant positive effect on plant preference. People show high preference for blue and green in a visual environment. People exposed to colorful flowers in a green background showed more positive attitudes and active brain functions (Jang et al. 2014). Thus, it is necessary to plant preferred plants in places that require high comfort and relaxation and enhance the value unique to the space.

Ninth, restoration outcomes of garden visitors had a significant positive effect on plant preference. This indicates that higher restoration outcomes of garden visitors lead to higher preference for plants that are not commonly found around, plants that bloom in a variety of colors, and plants with a lot of fragrance. Since gardens are composed of nature-friendly materials, people who experience positive energy from plants stay longer in the garden and are more likely to revisit. It is necessary to continuously analyze plant preference and psychological state of visitors and create gardens as spaces that can be enjoyed for a long time by developing various garden tourism and experience programs.

The limitations of this study and suggestions for further research are as follows. First, there are limitations in generalizing the results since this study was conducted on only 6 gardens involving 360 visitors, and thus research must be conducted on a greater number of samples. Second, further research must secure a sufficient number of gardens since the number of registered gardens is increasing every year. Third, since 51.4% of the participants in this study are in their 50s or older, further research must continuously investigate the effects of gardens by conducting a pretest and posttest on participants of more diverse age groups.

This study showed that visiting gardens had effects on promoting perceived restorativeness and restoration outcomes of adults as well as on differences in plant preferences. Therefore, visiting gardens will contribute to relieving mental stress, improving the quality of individual life, and fulfilling green welfare for a healthy life. This study has significance in comparing national gardens, local gardens, and private gardens to verify the effects of promoting perceived restorativeness and restoration outcomes of visitors and the differences in plant preferences. The results of this study are expected to be used as the basic data for promoting the use of gardens, hopefully establishing a high-quality garden culture by applying the factors affecting garden visits to garden operation and management plans considering the visitors.