Analysis of Performance Factors According to the Operation of Care Farms

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

This study was conducted to understand the current status and performance factors of domestic agricultural management in order to develop a business model that meets the needs of the times along with the newly emerging demand for agro-healing

Methods

An online survey was conducted on 170 care farming business entities nationwide, and the collected data were frequency-coded using SPSS Ver.25. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to extract performance factors, and a reliability analysis was performed to verify internal consistency for each factor.

Results

The factors that determine the performance of care farms, such as sales and profits, were classified into seven performance determinants (X1 to X7). Factor 1 was classified as one factor by grouping X2(excellence in use of animals/plants), X6 (program excellence), X5(quality of facility), and X3 (size of facility) together, and Factor 2 was classified as one factor by grouping two items, X7 (governmental support) and X1(location) together, showing high internal consistency between all Cronbach’s α. The correlation between the factors determining care farm performance did not have statistically significant results between X7 (governmental support), X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants), and X6 (excellence in program), but overall, there was a correlation between items that was statistically significant. A regression analysis was conducted to determine the variables affecting the performance factors of care farms, and at the 95% confidence level, both the location and sales of care farms were statistically significant.

Conclusion

Care farms that provide care farming services were often operated on a small scale because they didn’t have a sufficient base of profit, with the exception of farms operated in connection with former rural education farms. In the future, it is considered for care farms necessary to utilize factors of regional differentiation, such as the locational environment and the characteristics of the region, or to link with multiple targets and institutions in the region.

Introduction

Well-being, which was originally focused on improving human health and quality of life, is changing into a healing trend that pursues a happy and sustainable life by both healing humans and restoring nature. Since the 2000s, as numerous issues including the aging of the population and urbanization have spread worldwide, care farming has been in full swing, primarily in developed countries, with the aim of improving mental and physical health (Cho et al., 2019). Care farming is also done on a small scale in South Korea with a focus on farmhouse or farm experience activities, and takes a range of approaches including horticultural therapy, animal therapy, and forest therapy. Although it is still in its infancy, it continues to grow (Bae et al., 2019). In the early days of its introduction, care farming was developed centering on experience-based agri-tourism, but now it is spreading with the goal of improving the physical and mental health and rehabilitation of participants, aiming to alleviate problems of modern people such as anxiety, depression, and stress through exposure to nature (Lee et al., 2020). It is also developing rapidly with various age groups participating in it, from elementary school students to teenagers, adults, and senior citizens. The healing trend, which emerged after 2010, has been rapidly spreading through the press and mass media in line with the social atmosphere that promotes the benefits of relaxation, health, and mental stability, and it is currently making a meteoric rise to the extent of forming a large industry in the fields of broadcasting, books, and leisure. In accordance with this social trend, care farming is also being done in the field of agriculture to obtain healing functions through various activities using plants and animals with the goal of achieving a happy and sustainable life (Kim et al., 2014).

As the paradigm surrounding global and national healthcare policies has recently shifted to one of preventive healthcare, various topics related to “healing” are frequently being mentioned in the media. Care farming, which improves the quality of life of urban residents and provides “relaxation,” is also reported on through the Internet or social network services, and the number of related searches is steadily increasing. The legal institutionalization of care farming has been promoted, and on March 25, 2021, the Act on Research, Development and Promotion of Healing Agriculture (hereinafter referred to as the “Agro-healing Act”) was passed at the plenary session of the National Assembly, raising national interest in care farming service businesses. However, since detailed information on various profit models for beginners in this business is lacking, including the creation of business places for care farms, resource utilization, and profitable value creation, a performance model of input resources for the creation of business places is urgently required. Therefore, this study examined the business models of care farms and surveyed the operating status of related domestic agricultural business entities (ABEs) to develop a business model that meets the times along with the increasing demand for care farming, which is newly emerging. Of those, this study aims to analyze the performance determinants that affect the operation of care farms, which were derived through review of the following previous studies (Yoo et al., 2021a; Yoo et al., 2021b; Yoo et al., 2021c; Bae et al., 2019).

Research Methods

Survey subject and method

This study examined the operating status of care farms as part of research to develop strategic plans for a care farm business model. To this end, a survey was conducted for 40 days from October to November 2022, targeting 170 ABEs that had provided care farming programs to their users out of 349 farms and villages nationwide supported by national and local funds. To secure the representativeness of the survey samples, the number of samples was selected based on the population proportion by region, which was presented by company B, a domestic specialized research institute in Seoul. The survey was conducted online, in a non-face-to-face manner. After the purpose of the survey and matters to be noted when responding were fully explained to the respondents, the survey was conducted using the self-report method, in which they responded directly to the questionnaire.

Survey contents

The survey items consisted of a total of 10 items, including 3 items on demographic characteristics (gender and age group of business representatives, and location of work-place); 5 items about the general status of care farms (whether the representative is a farmer, type of facility, number of workers, total sales of facilities, and income/sales of care farming); and 2 items related to the performance of care farms. There are many items that determine the performance of care farms, including sales and profits, but these were derived through a review of previous studies prior to proceeding with this study. The performance determinants of care farms were proposed by Bae et al. (2019), and are as follows. X1 (location), X3 (facility size), X5 (facility quality), X4 (promotion/marketing), X6 (program excellence), and X7 (governmental support) were suggested in the policy priorities for revitalizing care farming services. X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants) relates to agricultural materials grown on a farm and represents excellence in being used for healing effects such as things to eat, see and enjoy. X5 (facility quality) represents the quality of facilities used to provide care farming services, including experience centers, vegetable gardens, education centers, convenience facilities, and cultivation facilities. X6 (program excellence) represents the excellence of the program provided for healing, including purposiveness, structure, content, and progress. X7 (governmental support) refers to operational support including materials or consulting provided by the central or local governments so that care farming businesses can be operated (Table 1). Differences were rated on a 5-point Likert scale for each of the 7 items derived. The higher the score, the better the evaluation: 1 point is “Poor”; 2 points is “Somewhat poor”; 3 points is “Average”; 4 points is “Somewhat good”; and 5 points is “Excellent.”

Data analysis

The total of 170 responses collected were aggregated and organized using Excel 2016 (Microsoft, USA), and then were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM, USA). A frequency analysis was conducted on the characteristics of ABEs operating care farms, and a descriptive analysis was performed to analyze factors related to the performance of care farms (based on the average evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale). Then, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to extract performance factors, and an internal consistency analysis was performed to check the homogeneity between variables constituting the factors (Cronbach’s α). For EFA, factors were extracted through Varimax rotation among orthogonal rotation methods using principal component analysis (PCA), and only factors with an eigenvalue of 1 or more were extracted and classified. To check the internal consistency of each factor, a reliability analysis was conducted to calculate the Cronbach’s α coefficient, verifying the internal consistency of each factor. A regression analysis was performed at a 95% confidence level to determine the variables that affect the performance factors of care farms.

Results and Discussion

General characteristics of ABEs operating care farms

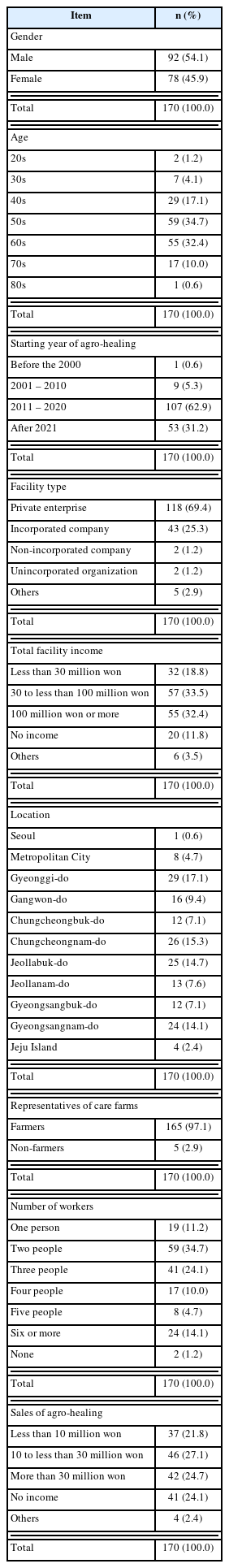

The general characteristics of ABEs operating care farms are shown in Table 2. The gender breakdown of the representatives was 92 males (54.1%) and 78 females (42.3%). In terms of age, no respondents were younger than 20 years old, with 59 people (34.7%) in their 50s representing the majority, followed by 55 (32.4%) in their 60s; 29 (17.1%) in their 40s; 17 (10.0%) in their 70s; 7 (4.1%) in their 30s; 2 in their 20s (1.2%); and 1 person in their 80s (0.6%). In terms of their location by region, Gyeonggi-do had the most with 29 people (17.1%), followed by Chungcheongnam-do with 26 (15.3%); Jeollabuk-do with 25 (14.7%); Gyeongsangnam-do with 24 (14.1%); Gangwon-do with 16 (9.4%); Jeollanam-do with 13 (7.6%); Chungcheongbuk-do and Gyeongsangbuk-do with 12 each (7.1%); Metropolitan Cities with 8 (4.7%); Jeju Special Self-Governing Province with 4 (2.4%); and Seoul with 1 (0.6%). For the starting year of care farms, the majority were started between 2011, when care farming began to be studied, and 2020, with 107 farms (62.9%); this was followed by after 2021 with 53 (31.2%); from 2001–2010 with 9 (5.3%); while only 1 (0.6%) was started before 2000. The increase in the number of care farms after 2010 seems to be the result of the introduction of the 6th industrialization, which combines processing, sales, and services for increased added value, improved farm household income, and job creation in the existing cultivation-oriented agriculture (Kim and Heo, 2011). In terms of the type of facility, private enterprises accounted for the majority with 118 (69.4%), followed by incorporated company with 43 (25.3%); others with 5 (2.9%); and non-incorporated company and unincorporated organizations with 2 each (1.2%). This is a similar finding to that of Yoo et al. (2021b) on the current status of care farm business, and the operational status of Italian social farming reported by Roberta et al. (2020). It indicates that small-scale private farms account for an absolutely large portion of the business utilizing the healing function of agriculture. It was found that the 165 care farms (97.1%) whose representatives were farmers accounted for the majority, while the remaining 5 farms (2.9%) had non-farmer representatives. In terms of the number of workers in care farms, farms with 2 workers were the largest group at 59 places (34.7%), followed by farms with 3 people at 41 places (24.1%), farms with 6 or more at 24 (14.1%), farms with 1 at 19 (11.2%), farms with 4 at 17 (10.0%), farms with 5 at 8 (4.7%), and farms with none at 2 (1.2%). For total facility income, 30 to less than 100 million won was the highest at 57 places (33.5%), followed by 100 million won or more at 55 (32.4%); less than 30 million won at 32 (18.8%); no income at 20 (11.8%); and non-responses at 6 (3.5%). Yoo et al. (2021b) reported that projects conducted in care farms were similar to those operated centering on community services by educational institutions or social welfare facilities. For care farming sales, 10 to less than 30 million won was the largest group, at 46 places (27.1%), followed by 30 million won or more at 42 (24.7%), no income at 41 (24.1%), less than 10 million won at 37 (21.8%), and no response at 4 (2.4%).

Factors related to care farm performance

Correlation analysis of care farm performance determinants

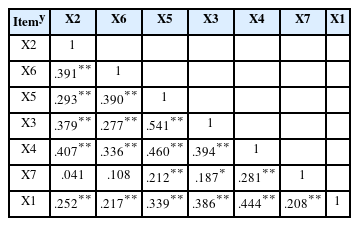

Prior to proceeding with this study, Pearson’s R value was obtained, which is a correlation coefficient between items that determine performance (i.e., performance determinants) including sales and profits of care farms derived from the review of previous studies. Based on this, as shown in Table 3, all items had correlations at a significance level of 5% and were statistically significant, excluding X7 (governmental support) and X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants), and X7 (governmental support) and X6 (program excellence). However, Kang (2016) presented that a correlation coefficient of 0.39 or less represents a weak association, so it can be seen that performance determinants have low correlation, excluding X3 (facility size) and X5 (facility quality), X4 (promotion/marketing) and X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants), X5 (facility quality), X1 (location) and X4 (promotion/marketing).

Factor analysis of care farm performance determinants

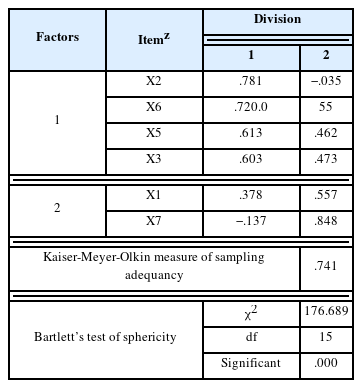

On the 7 performance determinants of care farms derived above, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted to assess the appropriateness of using factor analysis along with the explanation of terms. The KMO value, a coefficient that determines the appropriateness of the sampling mentioned by Lee (2003), was 0.789 and the significance level was .000, indicating the validity of the factor analysis with values close to 1 and 0.5 or higher, respectively (Table 4).

However, after deleting item X4 (promotion/marketing) which presented cross-loading between factors, a re-analysis also found a KMO value of 0.741 and a significance level of .000, showing the validity of the factor analysis (Table 5). Accordingly, based on the commonality of the items derived through the analysis of this study, the items were classified as internal factors (Factor 1) or external factors (Factor 2). Factor 1 was classified as one factor by grouping X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants), X6 (program excellence), X5 (facility quality), and X3 (facility size) based on their importance, and named “internal factor.” Factor 2 was named “external factor” by grouping the two items X1 (location) and X7 (governmental support) into one factor.

Internal consistency analysis by care farm performance determinant

By selecting items that determine the care farm performance and conducting a reliability analysis of them to assess the internal consistency of each factor, as shown in Table 6, it was found that the Cronbach’s α of Factor 1 and 2 was .709 and .566, respectively, representing high and acceptable internal consistency. Regarding internal consistency, Kang (2016) suggested that a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.5 or higher is a reliable value, so it seems that the construct of care farm performance determinants was good and acceptable. In addition, when an item deleted, the α coefficient showed a lower value than the total α coefficient, ensuring reliability as a measurement tool.

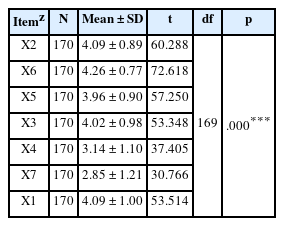

Performance determinants based on the characteristics of care farms

By evaluating their own farms for the performance determinants of care farms, the remaining five factors were found to be generally well-evaluated, ranging from 3.96 to 4.26 on a 5-point scale, excluding 2.85 for X7 (governmental support) and 3.14 for X4 (promotion/marketing). They also showed a statistically significant difference (Table 7).

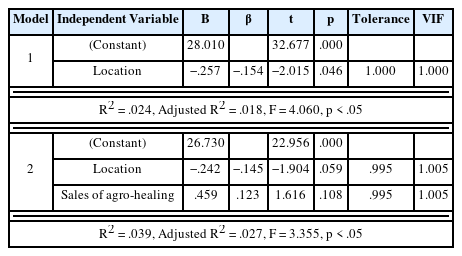

To determine the variables that affect the performance of care farms, a multiple regression analysis was conducted, with the locations of care farms and sales of care farming as independent variables, and care farm performance determinants as dependent variables (Table 8). As a result, both the location of care farms and sales of care farming were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. This suggests that these items also affect the determination of care farm performance determinants, as reported by Yoo et al. (2021b). They took the case of a healing farm in the Netherlands as an example of the establishment and vitalization of the care farm business and reported that the annual sales and location of farms affected the expansion and maturity of the market. Therefore, for the development of care farming, it is necessary to consider the locational conditions and create farms focused on regional differentiation, including regional characteristics or major potential users, and linking with institutions in the region. Considering the regional environment and diversity, it seems that care farms will develop into a converged form of agriculture, welfare, and education, if the basis for an in-depth analysis and understanding of the specific status is established.

Conclusion

To develop a business model that meets the times with the growing demand for agro-healing which is newly emerging, this study was conducted to determine the current status of domestic agricultural business entities (ABEs) related to care farms and their performance determinants. From October to November 2022, a non-face-to-face online survey was conducted on 170 ABEs related to care farms nationwide by company B, a domestic specialized research institute, and the results are as follows.

First, in terms of the general characteristics of ABEs operating care farms, the majority of representatives were male (92 persons, 54.1%), and their age and location by region were mostly in their 50s (59 persons, 34.7%) and in Gyeonggi-do (29 persons, 17.1%), respectively. As the starting year of care farming, most were established between 2011, when care farming began to be studied, and 2020, with 107 places (62.9%). For the types of facilities, private businesses and farms whose representatives are farmers accounted for the majority at 118 (69.4%) and 165 places (97.1%), respectively. For the number of care farm workers, the most common number was 2 people at 59 places (34.7%). For the total facility income and sales of care farming, the largest groups were 30 to less than 100 million won (57 places; 33.5%) and 10 to less than 30 million won (46 places; 27.1%), respectively.

Second, the items that determine the performance of care farms, such as sales and profits, were classified into 7 performance determinants: location, excellence in the use of animals/plants, facility size, promotion/marketing, facility quality, program excellence, and governmental support, based on a review of previous studies. Although there was no statistically significant correlation between X7 (governmental support), X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants), and X6 (program excellence), which are performance determinants of care farms, there was a correlation between the overall determinants, and this correlation was statistically significant.

Third, of the performance determinants of care farms, X2 (excellence in use of animals/plants), X6 (program excellence), X5 (facility quality), and X3 (facility size) were classified as Factor 1 based on their importance, and named “internal factors.” The two determinants, X7 (governmental support) and X1 (location), were grouped into Factor 2 and named “external factors.” Cronbach’s α of Factor 1 and 2 was .709 and .566, respectively, indicating high and acceptable internal consistency.

Fourth, for the satisfaction evaluation of their own farms according to the performance determinants of care farms, the remaining 5 determinants were generally well-evaluated, ranging from 3.96 to 4.26 points on a 5-point scale, excluding X7 (governmental support) and X4 (promotion/marketing). By conducting a regression analysis to determine the variables affecting the performance of care farms, it was found that both the location of care farms and the sales of care farming affected the determination of the performance, a finding that was statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

Care farms were often operated on a small scale since they did not have a sufficient base of profit, excluding those which had been operated previously in connection with rural education farms. For the development of agro-healing in the future, it is necessary to consider the locational conditions and focus on regional differentiation, including regional characteristics that can greatly utilize the conditions, or major potential users, and linking with institutions in the region. In addition, considering the regional environment and diversity, it seems that care farms will develop into a converged form of agriculture, welfare, and education, if the basis for an in-depth analysis and understanding of the specific status is established. This study has a limitation in that by conducting a survey on ABEs that are engaged in the care farming business, it did not have a large number of samples in population sampling. Nevertheless, it can be useful as basic data for establishing a care farm business model. Furthermore, a business model (draft) for agro-healing will be suggested in the future as an in-depth case study of care farms for business strategies of care farming services.