A Study on Residents’ Perception towards the Importance of Forest Therapy in the Central Region of China: Based on the Cases in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Recently, forest therapy has received strong support from the Chinese government and gradually embarked on the road of development. However, compared with South Korea, forest therapy started late in China. And it is still in the exploration stage of theoretical research and industrial practice. To study the development of forest therapy in China, we review the legal system and development of forest therapy in Korea. This study uses online surveys to help us understand the level of awareness of the importance of forest therapy in central China. And it also provides a reference for the further development of forest therapy in China.

Methods

The methods used for this analysis were Chi-square test, one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), principal component analysis (PCA), and one-way Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) .

Results

Our findings showed that the perception about forest therapy was significantly different among people with different educational level (χ2 = 25.526, p < .001). The cognition of forest therapy is significantly different from the cognition of the importance of natural healing projects (p < .001) and pro-environmental projects (p < .001). Moreover, there was a significant difference in the perception towards the importance of 18 forest therapy facilities and 9 industrial development influencing factors with or without forest therapy awareness.

Conclusion

The conclusion is that our participants have low awareness of forest therapy, but they have great expectations of forest therapy. In addition, the forest environment and emergency medical facilities reflect the recognition of the importance, including treatment programs, treatment facilities and factors affecting industrial development. Therefore, considering the successful experience of forest therapy in Korea, this study proposes practical measures to strengthen publicity, facility construction and treatment program development.

Introduction

More than 40 years since the reform and opening-up in China, it has experienced the largest population movement and the subsequent urbanization process in human history (Ren et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Rapid urbanization has transformed human living space from a natural environment to an artificial environment and exposed them to various environmental pressured that has threatened human health (Choi et al., 2011; Nowak et al., 2018). The environmental pressure brought by urbanization will have negative effects on human physical and mental health and may induce chronic diseases such as cardiovascular, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes (Tsigos and Chrousos, 2006; Friedman and Silver, 2007). It has also affected mental health and caused mental disorders such as fatigue, restlessness, and depression (Lederbogen et al., 2011; Dey et al., 2014).

In recent decades, the number of chronic disease cases in China has been increased due to urbanization (Gong et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2014). According to China’s National Health and Nutrition Big Data report, there are more than 300 million patients with chronic diseases, 7.376 million people die because of chronic diseases each year (Li and Wang, 2017), chronic diseases have become the main threat to people’s lives and health (Yi, 2020). In addition, stats of World Health Organization (WHO) has showed that more than 95 million people are suffering from depression in China, accounting for 7.3% of the total population (Huang et al., 2019). Moreover, the National Bureau of Statistics of China showed that the population over 65 years old in China accounted for 13.5% (191 million) of the total population in 2020 (Wang et al., 2022). Many research institutions such as Citic Securities predict that China will enter an aging society before 2025 (Sun et al., 2022).

Despite the rapid development of modern medical technology, it is difficult to identify the pathology of various chronic diseases. However, people are increasingly interested in forests’ prevention and treatment methods that has a significant effect on lifestyle. By spending time in a green and healthy environment, forest therapy offers a preventive alternative to cope with stress and to improve people’s health and well-being (Song et al., 2015). Due to the surge in the aging population, people are focusing on forest healing, which is a new form of China’s forest therapy industry (Ren, 2016; Zhang, 2020; Li and Chen, 2020).

Since the introduction of forest healing in 2012 (Xie et al., 2019), the state has actively promoted the development of this emerging industry in China. According to the Opinions on Promoting the Development of Forest rehabilitation and recreation industry, Forest therapy is a convergence industry. It centered on the development of forest resources, which integrates tourism, rest, medical treatment, vacation, entertainment, sports, health management, and post-aging life services, and other new concept in health care services. It is of great significance in society, not only to meet the demand for health management but it also serve as a national interest with various ecological benefit (Park, 2020; Shin et al., 2011).

In the Health China 2030 Plan, it is emphasized that health is an inevitable requirement for the all-round development of mankind, the cornerstone of economic and social development, an important indicator of national prosperity, and a common pursuit of the people (Li et al., 2018). In addition, the concept of “Clear waters and green mountains are as good as mountains of gold and silver” promulgated by President Xi Jinping. It implies the harmonious coexistence and common development of humans and nature, which is closely related to forest therapy (Wen, 2022). Based on the demand for aging and health needs, China actively cooperates with foreign governments and organizations, led by the State Forestry Administration. On March 26, 2015, China and Korea signed a memorandum of understanding on forest welfare cooperation (National Forestry and Grassland Administration, 2017), which actively communicated forest recuperation, healing, and education. At the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) meeting in August 2016, South Korea and China agreed to strengthen economic exchanges, and expand industrial cooperation, innovation cooperation, and modern service cooperation (Zhang and Jin, 2017).

Currently, there are different characteristics and paths to forest therapy development in different countries. Among countries worldwide, Korea has established the world’s first forest welfare service system (Dodev et al., 2020) based on the established forest policy to advance public welfare by flexibly utilizing forest facilities and therapy programs. In addition, the Korean government has provided efficient legal protection for the development of forest therapy, and relevant practice. Also it is a significant reference for other countries to build forest therapy systems. Moreover, Korea’s forest welfare service infrastructure is also very sound, which includes the construction and management of healing forests, program development and evaluation, and an instructor training system, which has a systematic and strict institution for providing practical experiences in the construction of bases and operation of therapy products. South Korea and China both belong to East Asia, and they have relatively consistent Confucian ideological traditions, customs, elderly care demands, etc. In August 2016, China expressed its intention to strengthen economic exchanges between China and Korea and expand industrial cooperation, innovation cooperation, and modern service industry cooperation at the Asia Economic Cooperation Conference (Ji, 2019). Therefore, it is very important to borrow the best practices from Korea’s development of the healthcare industry and promote the cooperation of the health industries between the two countries.

However, the forest therapy industry in China started relatively late and is in the stage of theoretical research and exploration of industrial practice (Zhu et al., 2020a; Duan and Li, 2019; Shu et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2022; Qian and Shen, 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2022). Therefore, to better promote the industrialization of forest therapy and improve the forest therapy service system, this study focuses on Korea as an example examining the developmental process of forest therapy. Moreover, this study has investigates the perception towards the importance of forest therapy programs, facilities, and industrial development factors using an online questionnaire. Further, it provides development directions and references for base construction, program development, legal system building, professional qualifications, etc.

In this study, awareness of forest therapy refers to whether respondents have heard of forest therapy effects and how it functions. Hong’s (2012) study found that the ex-anti perception made a difference in the perception towards the importance of the forest healing programs. In another study, awareness of forest therapy had a significant implication on use of healing facilities (Son et al, 2022). The study by Chang and Yoo (2016) concluded that a healthy forest environment and accessibility of facilities should be ensured when providing forest welfare services. In addition, Goodhardt et al. (1984) have proposed a model in which purchase (use) intention consists of three stages: awareness, trial, and repurchase (reuse). Therefore, the following hypotheses are envisaged for the development and feasibility of the forest therapy industry.

H1. A significant difference in the importance perception of forest therapy programs depends on whether people are aware of forest therapy.

H2. A significant difference in the importance perception of forest therapy facilities depends on whether people are aware of forest therapy.

H3. A significant difference in the importance perception of forest therapy industrial development factors depends on whether people are aware of forest therapy.

Forest therapy in South Korea

In 2006, Korea began to construct the healing forest. Medical scientists and forest scholars have established a juridical association Forest Healing Forum to actively explore the construction of healing forests (Korea Forest Service, 2017). In 2008, Korea Forest Service selected the suitable spaces in recreation forests to build the healing forests. And the Saneum Natural Recreation Forest area in Yangpyeong-gun, Gyeonggi-do was chosen as a demonstration site for the “Healing Forest Model”, which was officially opened in 2009 after a trial run (Korea Forest Service, 2009). Subsequently, the construction of the National Baekdu Daegan Forest Healing Park by the Korea Forest Service, which began in 2010, provided an opportunity to generate interest and investment in the mountain village area, and it has generated a positive response from local self-governing bodies for forest therapy. After the completion of the Saneum forest, the demonstration project of the mountain-village connection model of the Jangseong Hinoki Healing Forest located in Jeollanam-do, and the demonstration project of the experience facility connection model of the Hoengseong Healing Forest located in Gangwon-do has been opened. Then, through these demonstration projects, 148 billion won of national funds were invested from 2010 to 2016 to build the “National Center for Forest Therapy” for short-term stay and healing experience, which included forest healing facilities such as a health promotion center, training center, healing village, research center, healing forest road, and other facilities (Lee, 2016).

From 2009 to 2021, 69 ‘healing forests’ and ‘forest healing centers’ have been built across the country (Choi, 2021), which are divided into national, public, and private according to the ownership and operation entities. The Korea Forestry Service has divided the types of therapy facilities into ‘forest healing facilities’, ‘sanitation facilities’, ‘convenience facilities’, ‘electrical communication facilities’, and ‘safety facilities’. They also set up construction standards for the active development and standardized management of the forest therapy industry.

Along with the opening of the forest therapy system, laws related to forest therapy have gradually emerged. In 1990, “The Forest Law” was revised to include part of forest recreation, forest culture, forest education, and forest therapy. In 2006, the Forest Act was subdivided into the Forest Resources Composition and Management Act, the State Forest Management Act, and the Forest Culture, and Recreation Act. To provide a comfortable and safe forest culture and recreation service for people, “The Forest Culture Recreation Act” was revised in 2010 to provide a legal basis for the construction of healing forests by stipulating matters related to the preservation, utilization, and management of forest culture and forest recreation resources. To maximize the effectiveness of health promotion, the qualification system for forest therapy instructors and the designation system for training institutions were established in 2011, which gave professionalism to those who instruct healing activities and provided a systematic basis for training professionals (Korea Forest Service, 2017; Li, 2021).

In addition, the Forest Service collected various opinions and consultations from experts and a blueprint was established to promote national health through the flexible operation of forest therapy and the formulation of “Forest Therapy Activation Promotion Plan” on May 7, 2012 (Korea Forest Service, 2012), helped in the expansion of forest therapy infrastructure which addresses 10 specific topics in 5 fields.

The Korea Forest Service has divided the human life span into seven stages and implemented the G7 plan to provide forest welfare at each stage, and enacted the Forest Welfare Promotion Act (Korean Law Information Center, 2021) on March 27, 2015. The law contains 7 chapters and 66 articles which provides legal protection and action guidelines for the establishment of the forest welfare service system in Korea, It provides lifelong provision of forest welfare services, and strengthen the support for the disadvantaged groups of forest welfare, such as the disabled and low-income groups. These groups are more entitled to use forest welfare services (voucher system). In addition, the Korea Forest Welfare Promotion Institute (KFWPI) was established on April 18, 2016, under the Department of Korea Forest Service to provide professional and systematic forest education and welfare services (Hong and Lee, 2018).

Research Methods

Data collection

To ensure the diversity of respondents, we used an online survey method with random sampling to recruit respondents (18 ≤ people aged ≤ 65). From June 9 to July 8, 2021, by posting an announcement on the bulletin boards on the platforms of “Baidu Tieba”, “Sina Weibo”, and “WeChat Moments”. In the announcement, the purpose and content of the questionnaire were fully explained to the participants, and the research was conducted after obtaining their consent. The samples were designed through a survey software called “Questionnaire Star” to create a questionnaire format and generate links. After that, the links were shared on “Baidu Tieba”, “Sina Weibo”, and “WeChat Moments”. The entire questionnaire survey process was completed by sampling through the above three social platforms. A total of 309 Residents from central China such as Henan, Shandong, and Jiangsu participated in the survey, the total number of questionnaires collected is 336, to ensure the validity of online questionnaires, 309 valid questionnaires with a response rate of 92 percent were obtained by excluding 27 invalid questionnaires that did not meet the requirements.

The study approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University (IRB number: CBNU-202106-HR-0057) prior to initiating the study.

Questionnaire design

Although some scholars have investigated the perception and demand for forest healing in China, but it was not accurate positioning for product development, program operation, and base construction of forest healing due to incomplete perception and information asymmetry. Therefore, we designed a questionnaire to evaluate the more comprehensive perceptions of China’s central area residents toward forest therapy. Firstly, to analyze the respondents’ characteristics, we included items about the demographic background, visit motives, and perceived approach. This study on items of visit motives was based on the modification and supplementing of previous studies on the perception of importance, demand analysis, and preference for forest therapy (Hong and Lee, 2013; Huang et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022). In addition, the items of programs were designed based on the previous studies and 6 major therapies proposed by the National Institute of Forest Science of Korea in 2007 (Yoo, 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Kim, 2015; Jeong and Yeon, 2020). The items on facilities were composed by modifying and supplementing previous studies on treatment, accommodation, health management, and service (Yoo, 2011; Hong and Lee, 2013; Ko, 2009). Regarding the item about the influencing factors of industrial development, 9 items were chosen by investigating the researches of Yoo, 2011., Hong and Lee, 2013. and Ko, 2009. The items relating to users ‘ characteristics were designed on a nominal scale, and the other items were designed on a Likert scale (1 = very unimportant to 5 = very important).

Data analysis

The data collected for this study was analyzed using the SPSS Statistics 26 program (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The general characteristics, perceived approach, and purpose of participation were analyzed using frequency analysis, and the Chi-square test. These methods were used to determine the respondents’ perceptions of forest therapy. In addition, one-way ANOVA was used to determine whether there were differences in the perception towards the importance of forest therapy, facilities, and forest therapy industry development influencing factors. Further for dimensionality reduction PCA (principal component analysis) was used for 39 items, and MANOVA was used to analyze the items after dimensionality reduction. All statistical tests were used at a p-value of < 0.05 significance level.

Results

Experiences from Korea

Since 2008, Korea has been construction of healing forests, and the Forestry Service. It has established and expanded infrastructure for forest healing by setting standards for the construction of healing forests through the Forest Activation Promotion Plan. By the end of 2021, a total of 69 healing forests have been built nationwide. In addition, in 2006, the Forest Culture Recreation Act was enacted, which defined forest therapy and forest therapy programs. It regulated the forest environment in which forest healing activities were conducted. The forest therapy instructor system was introduced in 2011 to ensure the professionalism of forest healing programs. On March 27, 2015, the Forest Welfare Promotion Act was issued, which established the legal basis of forest welfare services by designating forests as a national welfare resource. The following year, Korea Forest Welfare Promotion Institute was established, and it is a specialized management agency dedicated to forest welfare work.

General characteristics of respondents about the survey

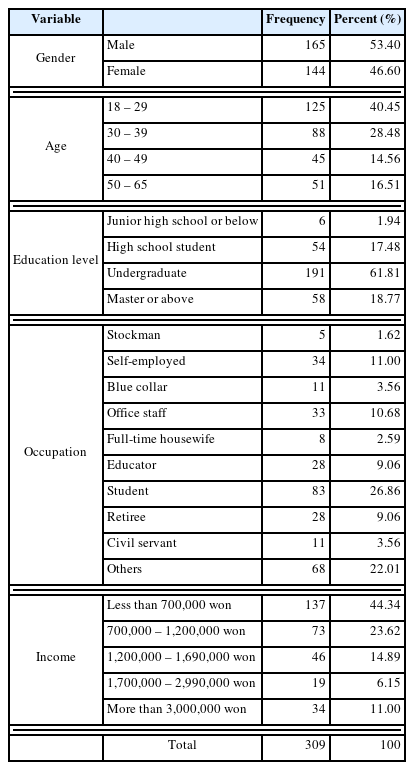

A total of 309 valid questionnaires were collected in this study. Table 1 gives the respondents’ perception of five questions about general characteristics. In the questionnaire survey, the proportion of males was 53.4%, slightly higher than that of females (46.6%). The age ranges were from 18 to 65 years old, with 40.45% were from 18 – 29 years old, 28.48% in 30 – 39 years old, 14.56% in 40 – 49 years old, and 16.51% in between 50 – 65 years old. From the perspective of age distribution, most of the respondents were in between 18 – 29 years old. In terms of education, the proportion of respondents with a bachelor’s degree are the highest (61.81%), followed by a graduate degree or above (18.77%), a high school degree (17.48%), and the rest (1.94%). In terms of occupation, students accounted for the highest percentage 83 (26.86%), 68 (22.01%) for the rest of the occupations, 34 (11%) for self-employed, 33 (10.68%) for white-collars, 28 (9.06%) for educators, 28 (9.06%) for retired, 11 (3.56%) for blue-collars, 11 (3.56%) for civil servants, 8 (2.59%) for full-time housewives, and the lowest proportion of Stockman(1.62%). The highest percentage of the income distribution was 44.34% for those who had less than 700,000 won income, followed by 700,000 – 1,200,000 won (23.62%), 1.2 – 1.7 million won (14.89%), 2.4 million won above(11%), and 1.7 – 2.4 million won (6.15%).

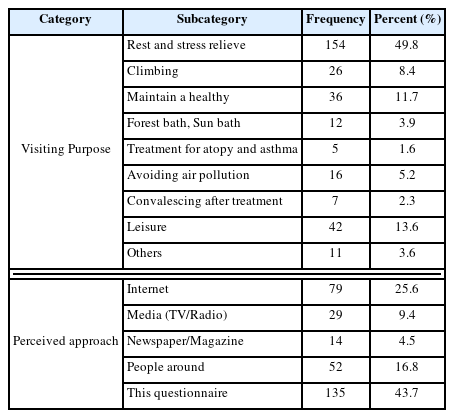

Table 2 shows, the respondents’ answers regarding the purpose of forest therapy were rest and stress relief for 49.8%, participating in leisure activities accounted for 13.6%, maintaining health accounted for 11.7%, climbing accounted for 8.4%, avoiding air pollution accounted for 5.2%, forest bathing accounted for 3.9%, others accounted for 3.6%, recuperation after the disease occurred accounted for 2.3%, and 1.6% for environmental disease treatment. This result showed that almost half of the respondents cited forest healing as a way of mental restoration, but they have little knowledge of other benefits about it. In terms of perceived approach, we can see that 43.7% of the respondents were informed through this questionnaire, followed by the internet (25.6%), people around (16.8%), media (9.4%), and newspapers (4.5%). In general, more than half of the respondents gained knowledge about forest healing through various channels, but nearly half of them did not know about it before this survey.

Perception of Forest Therapy

A chi-square analysis was conducted to determine whether there was a significant difference in the general characteristics of the investigators in perceptions of forest therapy. As shown in Table 3, the education was a significant factor that create difference in opinion about the perception of forest therapy (χ2 = 25.526, p < .001), 43 (74.1%) of those with Master or above having the highest awareness of forest therapy, 29 (53.7%) with high school graduates, 3 (50%) with Junior high school graduates or below, and 71 (37.2%) with Undergraduate. In addition, income was significantly correlated with the perception of forest therapy among the respondents who have awareness of forest therapy, 28 (60.9%) earned 1.2 to 1.7 million won per month, 42 (57.5%) earned 0.7 to 1.2 million won per month, and 15 (44.1%) earned more than 3 million won per month.

Analysis of variance

Perception of forest therapy programs

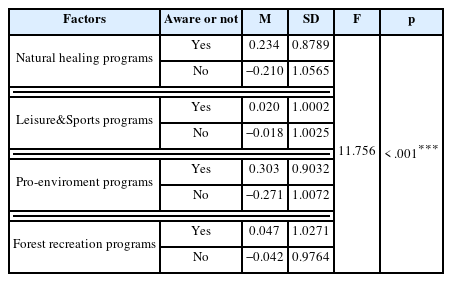

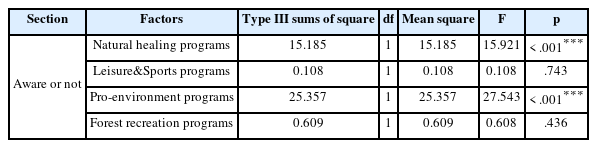

In this study, 39 forest therapy programs were subjected to dimensionality reduction analysis and subdivided into 4 types of therapy programs, namely natural healing programs, leisure&sports programs, pro-environment programs, and forest recreation programs. Among them, natural healing programs include meditation, landscape viewing, forest bathing, foot bathing, sound finding and other five senses experience programs, leisure& sports programs include camping, golf, survival games. The pro-environmental program reflects the close contact and flexible use of forest resources, such as medicinal food and tree planting. The recreation program includes recreational activity such as barefoot walking, Qigong and night walking. Table 4 shows the results of the perception of forest therapy programs, with significant differences in the perception towards the importance of therapy programs (p < 0.001) based on whether the forest therapy was known or not, and respondents with perceptions rated the importance of each item higher. To determine the degree of differences that existed between the factors, we conducted an inter-individual effect test and results are shown in Table 5. The results showed that the perception towards the importance of both natural healing programs and pro-environmental programs has significant differences at the p < .001 level.

As seen in Tables 6 and 7, landscape viewing, nature sounds finding, hot spring, and hot/cold water foot bath were the most important forest therapy program for those who were aware of forest therapy. While the most important forest therapy program for those who were not aware of forest therapy was hot springs, landscape viewing, nature sounds finding, hot/cold water foot baths. It is noteworthy that both groups of respondents considered the forest recreation programs such as barefoot walking, rock climbing/rope game, Qigong, and night walking as least important programs. This result showed that there were more concerned about the therapy programs involving sensory participation whether they have knowledge of forest therapy or not.

Perception of forest therapy facilities

In statistical analysis (Table 8), we can see a significant difference in the importance of each forest therapy facility with or without forest therapy awareness. Respondents who were aware of forest therapy had a higher level of perception towards the importance of forest therapy facilities than those who were not aware of forest therapy. And respondents who were aware of forest therapy first considered emergency medical facilities, pulse/blood pressure measurement facilities, and service centers, while respondents who were not aware of forest therapy first considered emergency medical facilities, amenities, and pulse/blood pressure measurement facilities. In general, all of the respondents were more concerned about medical facilities and public facilities instead of the facilities where they can participate in natural healing activities or utilize healing factors to improve physical and mental health. In other words, the facilities that can promote physical and mental health were not fully perceived.

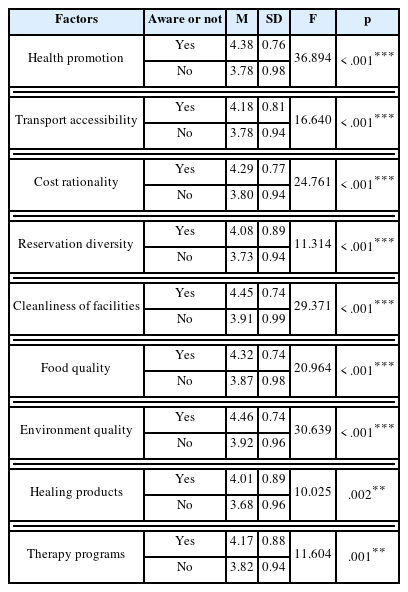

Perception of industrial development influencing factors

The analysis results in Table 9 show that there was a significant difference in the perception towards the importance of each industrial development influencing factors with or without forest therapy awareness. Respondents who were aware of forest therapy had a higher level of perception towards the importance of industrial development influencing factors than those who were not aware of forest therapy. We found that, regardless of whether they were aware of forest therapy, the surveyors’ first concerns were about the natural environment and the cleanliness of facilities, while the healing products and transportation were not a concern. This result posed a grand challenge to the industrial development of forest therapy, which may be due to the fact that most of the respondents still reside in the concept of forest tourism. Compared with forest tourism, forest therapy focuses on the quality and performance of bodily functioning, both cognitively and emotionally, including aspects of physical, mental, and social well-being. Healing products are different from tourism products, which are viewed as an opportunity to get close to nature, and people focus more on their visual experiences (Xie, 2019), while forest healing products also focus on physical and mental healing effects. In addition, while people pay attention to the experience of the forest environment and the facilities’ cleanliness is one of major concern when they visit the forest, however, transport accessibility determines the intention to use forest healing products.

Discussion

With the introduction of the Forest Culture Recreation Act, forest healing in Korea has rapidly developed, especially with the advent of the Forest Welfare Promotion Act, which marks that the Korean forest welfare service system has entered the track of institutionalization and legalization. Compared with Korea, in terms of forestry development in China, the newly revised Forestry Act (effective July 1, 2020) is of a basic law nature, and no special forest therapy laws have been formulated yet, and the current policy documents related to promoting the development of forest healing industry are not of a legal guarantee nature (Li, 2021). Generally, there are two major legislative problems regarding forest therapy in China: insufficient quantity and low quality. In Korea, the training and qualification examination system for professionals is organized by the state and managed in a hierarchical manner, which has played an active role in promoting the construction of the forest welfare service system and serving social development. The training system regarding forest therapy was introduced in 2015 at Beijing and other places in China (Huang et al., 2021b). It is still in the exploration stage and has not been expanded to the national level.

In the survey of this study, we investigated whether perceptions about forest therapy reflected significant differences in demographic characteristics of therapy programs, therapy facilities, and industrial development. These are some common influencing factors based on the perception of forest therapy. These factors are classified by gender, age, education, occupation, and income, we found that awareness of forest therapy was related to education and income, especially among respondents who obtained a graduate degree or higher (74.1%) and their monthly salary is between 1.2 million and 1.69 million won. In a survey on the perception of environmental pollution, respondents with higher education had greater awareness of smog hazards (Low et al., 2020; Philippssen et al., 2017). It may be possible to gain a better understanding of complex and large-scale problems through education, and the more education received, the more advanced their concepts are and the more comprehensive knowledge they will gain about new things (Lin et al., 2018). A study by Choi and Shin (2022) indicated that residents with an income of less than 2 million won had a higher awareness of the forest welfare complex. It presumed that this is because high-income people are more concerned with personal leisure activities than mass leisure activities, while people with low incomes are less concerned about things other than surviving. Secondly, respondents who knew about forest therapy were significantly different from those who did not know about natural healing programs (p <0.001) and pro-environmental healing programs (p <0.001). It is similar to Hong and Lee’s (2013) findings, there was a difference in the importance of natural healing programs and sports programs that are close to nature as mountaineering, forest bathing, and forest yoga according to whether or not the respondents know about forest therapy. The results of this study showed that respondents had a higher preference for natural healing programs to promote physical and mental health, and people who knew about forest therapy motivated them to have certain expectations about the efficacy of the healing program. Thirdly, the results of the survey on the perception towards the importance of forest therapy facilities and industrial development influencing factors showed that there were differences between groups for each survey. From the questionnaire results, we can see that the perception score of facility importance is consistent with the findings of Pu et al., (2019) Kweon and Kwon (2014) and Huang et al. (2021a) were medical facilities, infrastructure, accommodation, etc. are considered important. In this study, respondents who knew about forest therapy paid more attention to facilities than those who did not know. It follows that facilities are a part of the forest therapy industry, and their functions are easily ignored by those who lack knowledge. According to the result of industrial development influencing factors, all the respondents had high expectations for forest therapy, which was also reached in a study by Wei (2019) and Huang et al. (2021a) But perhaps because of the vague concept of forest therapy, which has failed to generate interest in exploring new things led to this difference.

The perception towards the importance of each therapy program was similar to the findings of Chae et al., (2021) the importance of viewing the forest landscape was considered an important healing item, which may be related to our daily life away from the forest and desire for a green environment. The respondents of this study scored high on the “emergency medical facilities” and “heart-rate/blood pressure measurement equipment” regarding the perception towards the importance of facilities. This result is somewhat different from the previous Hong and Lee (2013) demographic-based perceptions of therapy facilities, which found that facilities suitable for therapy programs were valued more than medical facilities. This is probably because the popularity of forest therapy in China is not high, and more efforts need to be invested in natural education. The facilities required for therapy programs as part of forest therapy are closed contact with therapy programs, and respondents did not score high on this because they lacked systematic knowledge of therapy programs and the facilities that apply to them. However, the factors that influence industrial development are ranked in order of their importance as “the benefits of the natural environment,” “the cleanliness of the facilities,” and “the ability to improve health,” respectively, it indicate that people are willing to participate in therapy programs with the forest environment. This is supported by a previous study on travel intentions for forest therapy, which showed that more than half of visitors focused more on the natural and cultural environment of forest therapy destinations (Zhu et al., 2020b).

Furthermore, in this study, 43.7% of respondents answered that they only learned about forest therapy through this questionnaire, which is a huge challenge for the development of the forest therapy industry in China. However, it is encouraging to note that the Chinese government is actively working to advance the industry process by actively promoting international exchange and cooperation through providing strong policy support.

This study explores the perceptions of residents in central China about major forest therapy facilities, operational programs, and industrial development influencing factors, complementing quantitative research on industrialization development. It expands the research towards the development path of the forest therapy in China (Yang et al., 2018; Song, 2020; Wu et al., 2018). In addition, we ranked the perception towards the importance of forest therapy programs, facilities, and industry development influencing factors. Then the data was used as the considerations for the facilities construction, program development, and industrial operation for future industrial development, and provide a basic reference for the development of forest therapy.

However, it is also important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Firstly, the questionnaire was collected online through social networking platforms, they pushed information based on the user’s preference, keyword search, and geographic location, resulting in a small sample size. And the samples were also affected by the age of internet users, with a large number of respondents in their 18~40 years old, so it is difficult to generalize the results of this study. Further research should be conducted in the field, and the sample size needs to be expanded to ensure the comprehensiveness of the results. Second, the health of the respondents was ignored during the survey, so it is difficult to determine whether the findings are related to health status. This misses the healing needs of diseased patients and does not provide data to support the development of healing programs for diseased patients. In addition, incorporating traditional Chinese medicine into forest therapy programs is an excellent opportunity to establish a distinctive brand of forest therapy.

Conclusion

Conclusions

In the past few years, national and local policies have continued to promote the development of the forest therapy industry. The relevant policies issued had attracted the attention of a large number of scholars. Among them, the emergence of research results such as base construction and evaluation standards, healing efficacy, and development paths (Wu et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Mao et al., 2012; Xiang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2021) has accelerated the pace of industrial development. However, what is more worthy of deeper consideration is the implementation of forest healing in China. Therefore, this paper has designed and implemented a questionnaire based on the research on the policies and regulations, facility construction, and program operation of forest therapy in Korea, in combination with the current situation of forest therapy in China. Moreover, this research provides pragmatic insights and suggestions on the development of programs and the operation of therapy facilities in China.

Through the survey, we came to know about the respondents’ awareness of forest therapy was not high, primarily because they have only been informed about forest therapy in a very limited way or they never heard of it. Although most of the respondents participated in forest therapy for relaxation and stress relief, their perception of forest therapy programs was only at the level of forest tourism. It includes viewing the landscape and finding nature sounds, and their perception toward the development of the forest therapy industry was also reflected in the natural environment. They were not aware of the fact that forest healing activities can have a positive impact on human physiology and psychology. In addition, the respondents’ perception of the importance of forest therapy facilities was more in favor of emergency medical facilities, because forest therapy was relatively new to most of the respondents and they confused the concept of infrastructure and therapy facilities. However, the purpose of their participation in forest therapy programs indicates that they have great expectations from forest therapy.

Suggestions

Improve the legal system

Recently, the management of forest tourism and forest therapy industries in China mainly relies on policy documents issued by the forestry, health, and civil affairs departments. There is no authority and guarantee of the policy documents, so it is necessary to actively promote forest therapy and related regulations and laws to improve China’s forestry legal system. It return this will provide fundamental guarantees and guidelines for the development of the forest therapy industry. Additionally, there is a need to revise the relevant laws to identify the forest industry in the form of laws and regulations.

Developing professionals

The purpose behind the realization of the healing function and the coordination of the forest therapy industry, it is necessary to introduce a human training system for forest healing instructors and to train forest healing instructors who can guide healing activities. Given this, a research committee composed of experts in related fields should be established which consists of a group of professors and lecturers who will be responsible for the intended education (Lee et al., 2013). In addition, forest therapy is an interdisciplinary industry that involves forestry, medicine, psychology, health care, and other fields. Thus, it emphasizes interdisciplinary collaboration, multidisciplinary participation, and multi-context talent cultivation (Zhang et al., 2020). Although some universities in China have set up forest recreation-related majors and the government has organized forest training courses for therapy instructors, but still there is a lack of systematic and authoritative assessment standards.

Strengthen publicity and popularize forest education

Most Chinese people do not know much about the efficacy and role of forest health care, so it is necessary to expand multi-channel publicity methods to increase public awareness. We should choose propaganda channels reasonably according to the needs of users, and use traditional media and Internet media to provide the necessary awareness. For example, videos can be used to explain the effects and benefits of forest therapy, offline public welfare lectures, and the establishment of e-commerce platforms for the promotion. In addition, to increase the awareness of forest therapy, we should launched forest experience activities during the student period, and forest education should be integrate into daily teaching work to strengthen basic education. We also can promote the forest health education in civic relying on enterprises and various social organizations.

Fully consider the professionalism and diversity of the forest facility

When constructing forest therapy facilities, we should consider how to utilize the healing function of forest environment elements and how to meet the preferences of forest visitors. First, it is necessary to provide facilities that can exert healing effects, such as forest bathing areas, sunbathing areas, and health promotion centers. Second, we can build and manage the facilities applicable to each healing program in different zones according to users’ needs. Considering that most of the trips are family-oriented, it is also necessary to build additional recreational healing experience facilities for young children, and pay attention to safety. Third, professionalism is requied in the construction process. Because health promotion facilities are an effective tool for meeting the needs of healing, which can influence the effectiveness of forest therapy. In addition, convenience facilities include ticket offices, parking lots, restaurants, and other supporting facilities, and how to put them into use and where to set them should be fully considered. Fourthly, forest trails must be maintained and managed continuously to provide a good forest therapy experience (Lee and Kim, 2001; Choi et al., 2021). Science the trails are the most utilized physical resources among the forest recreation resource, which directly or indirectly affect the quality of forest healing activities.

Develop therapy programs that meet consumer and societal needs

Consumer needs and social needs are very important in program development (Deng et al., 2022). Only by reflecting the demands of users in the program can make it a high-quality project (Kim et al., 2010). To strengthen the role of forest recreation, the direction of therapy program development should follow the principle of health promotion and physical and mental recuperation as the central goal. There is a need to develop diverse programs based on food therapy, hydrotherapy, phytotherapy, exercise therapy, spiritual therapy, and climate therapy that meet consumers’ and social needs. It is also important to be able to stimulate users’ motivation and interest in participation when developing healing activities (Lee and Jeong, 2012; Kim, 2015). Additionally, considering the different demands of visitors, the targeted and differentiated programs should be developed and evaluated.

Focus on all elements of industrial development and explore forest values

The superiority of the forest environment, the taste and quality of the food, the cleanliness of the facilities, the reasonableness of the charges, and the convenience of transportation are all important factors that concern the development of the industry and must be taken seriously. In addition, the establishment of an environmental monitoring system to quantify environmental indicators, allows visitors to understand the public welfare of the forest briefly. It also become convenient for managers to maintain the forest environment in time. Furthermore, as a big forestry country, China is rich in mushrooms and medicinal herbs in the forest (Xu, 2019), integrating these ingredients and medicinal herbs into forest therapy creates economic value by driving the development of understory products that are attached to forest therapy programs.