A Governance Structure Based on an Opinion Analysis of Local Stakeholders of Saemangeum Floating Photovoltaic Power Plants Project: Using Text Mining for Each Subject

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

As the use of renewable energy is expanding worldwide, conflicts are emerging in local communities due to environmental damage and competition for land use with existing industries, including agriculture and fishery. Accordingly, while many studies are trying to find alternatives to address such conflicts, studies on governance to implement these alternatives are insufficient. This study attempted to find options for the contentious field of renewable energy using text mining for each subject, and to suggest a direction for building governance to apply this in practice.

Methods

Text mining for each subject was conducted targeting the Saemangeum floating photovoltaic power plants (FPVs) project, a large-scale renewable energy project in Korea.

Results

As a result of the analysis, three clusters (stakeholder groups) were identified. First, local public officials complied with the government plan, as well as environmental activists from relatively remote areas. Second, local environmental activists and fishermen insisted on ecological conservation. Third, members of the public-private council (PPC) were concerned about industrial transformation. All groups shared a common perception that it was a renewable energy project that benefited the local ecological environment and people.

Conclusion

Based on this, local public officials will play a role in cooperating and arranging improvements in renewable energy projects, fishermen and local environmentalists will play a role in developing ecological environment-based renewable energy plans, and the PPC will play a role in seeking a direction for coexistence with the fishery and revitalizing the region. It was also possible to set the direction of governance to implement a project effectively. As such, establishing governance that is tailored to the area where a renewable energy zone is developed can be a starting point for managing local conflicts and operating a project efficiently.

Introduction

The use of renewable energy is spreading around the world to reduce carbon emissions and air pollution (Dincer, 2000; Moriarty and Honnery, 2012). However, various conflicts have occurred around issues that include environmental deterioration and acceptability to residents at local sites where renewable energy zones (REZs) are planned to be developed (Månsson, 2015). This occurs when there is a failure to develop a plan to characterize relevant regions through consultation with regional stakeholders on the development of a REZ (Díaz et al., 2017). To manage such conflicts at a site where a REZ is to be established, it is necessary to organize and compare the perspectives of stakeholders and suggest cooperative measures (Aslani, 2014). If the differences in their perspectives are not systematically organized, the conflict is highly likely to escalate into an emotional battle, in which the parties a re unaware of the cause.

Against this backdrop, many studies have dealt with conflicts in areas where REZs are developed, including wind and solar power. Various conflict issues have emerged, ranging from conflicts involving ecological damage (Voigt et al., 2019; Straka et al., 2020) in areas where REZs were established, to conflicts with existing industries including fishery (de Groot et al., 2014; Alexander et al., 2013). So, as an alternative, many studies have suggested renewable energy plans that consider the environment and symbiosis with existing industries. In presenting such an alternative, what is important is the establishment of governance over who, and how to implement it. If the roles of each subject are not properly established, it is not only difficult to obtain the impetus necessary to implement the suggested alternatives, but also dissatisfaction between the stakeholders may accumulate and cause a lack of communication and trust, leading to another conflict (Lange et al., 2018). If differences of opinion among stakeholders in planned REZs are not resolved by local governance, the project will eventually face difficulties caused by indigenous opposition and social conflict (Zárate-Toledo et al., 2019). In addition, even if local governance has been established, opposition from the local community may emerge where the appropriate roles and responsibilities are not assigned to the governance (Hindmarsh, 2010). In fact, one of the biggest issues of a public-private council (PPC) for renewable energy clusters is whether the council is properly formed and communicates with the local community. This indicates that there are problems with the governance of REZ.

Therefore, in this study, text mining for each subject (TMS) was performed that combined Q methodology and text mining (TM) to analyze differences in perception between subjects, and to propose governance based on this. TMS is a methodology which groups stakeholders that uses a lot of similar words by identifying which words a re used the most by each stakeholder (Lee, 2021; Lee and Kim, 2021). This methodology enables us to identify unexpected groups among various stakeholder groups, as well as common perceptions through keywords shared by everyone; based on this, it can help us determine the stakeholder structure unique to a region beyond general interests, and serve as a basis for establishing cooperative measures and governance.

This study aimed to examine the conflict of interest structure through TMS targeting the floating photovoltaic power plants (FPVs) project in the Saemangeum area, the largest renewable energy project in South Korea, and to propose a suitable governance system for it. The Saemangeum FPVs project is causing multiple conflicts despite its positive aim of generating energy by installing FPVs on unreclaimed land called Saemangeum. Various issues, including the location of the FPVs, the possibility of environmental pollution caused by solar panel waste, and ordering methods, have caused difficulties in the FPVs project (Lee et al., 2021). Accordingly, by determining differences in the stakeholders’ perceptions of the Saemangeum FPVs project, it was sought to explore an alternative for the project and governance for conflict resolution.

Management of conflicts over renewable energy zones

Although the expansion of renewable energy has the justification of the times to prevent environmental contamination caused by fossil energy, there a re cases in which indigenous species, including bats (Straka et al., 2020) and whales (Simmonds and Brown, 2010), are adversely affected at sites where REZs are established. These cases are defined as a green-green dilemma. To manage such conflicts, the need for a management plan for conflicts over REZs that fully considers the local natural environment has been raised. In this regard, studies were conducted to determine the appropriate location of REZs through environmental data analyses (Carrión et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2020) or public participation techniques (Müller et al., 2020; Plieninger et al., 2018).

Another major factor of the conflicts lies in the adverse impact of the industrial transition to renewable energy on existing agriculture and fisheries. Onshore solar and wind farms may reduce agricultural land (Späth, 2018), while offshore wind farms may encroach on fishing areas, causing friction with fishermen (Alexander et al., 2013). In this regard, alternatives were suggested, including making a greenhouse using photovoltaic (PV) panels (Marucci et al., 2018; Xue, 2017), or installing fish farms in offshore wind farms (Appiott et al., 2014).

What matters most of all in implementing these alternatives is how and by whom they will be implemented. Even if an alternative is proposed to carry out renewable energy projects in a way that is suitable for a region, the major responsibilities and tasks of each relevant subject should be well allocated to efficiently operate it (Ha and Kumar, 2021). Even if the environment is considered in a project and a direction for coexistence with existing industries is sought, damages to the environment and existing industries are likely to increase where appropriate managers for environmental conservation and energy conversion are not designated. A developer-driven project for offshore wind energy development on the isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico actually caused social schisms and conflicts. While the government-led attempt to manage this seemed to involve collecting some opinions from the residents, it did not constitute a governance in which local stakeholders properly participated. The negotiation process also did not change to a resident participatory method, which ultimately resulted in a failure in the implementation, as public sentiment against the project never eased (Zárate-Toledo et al., 2019). Even for a wind farm project in Australia, the environmental impact assessment (EIA) and participatory planning process were excluded by the project governance on the grounds that the government’s plan was reasonable and had no legal problems. Another project also faced opposition due to concerns about landscape destruction, and inadequate community engagement emerged as the primary governance issue, leading to expanding participatory governance (Hindmarsh, 2010).

Therefore, governance studies based on major issues that will enable us to allocate and manage the roles of appropriate local actors are needed (Lange et al., 2018; Niang et al., 2022). Despite this, studies on renewable energy stakeholders have thus far focused only on the conflicts themselves, so governance for conflict management and alternative implementation has not been discussed much. In addition, even research on governance for REZs dealt with the limitations of the government-led top-down method (Ha and Kumar, 2021), the importance of communication between the government and the public (Lange et al., 2018), and the significance of the geographical proximity of intermediary organization in cooperative governance (Niang et al., 2022); but did not specify a direction of how to actually establish such governance.

Text mining for each subject to build governance

Stakeholder analysis studies that aim to resolve conflicts related to the creation of REZs and seek cooperative measures have been reported. Such studies have ranged from examining the issues of a target site in qualitative terms through interviews with local residents and analyzing differences in perspectives (Colvin et al., 2016; Martinez and Komendantova, 2020), to more objectively determining differences in perceptions through surveys in quantitative terms. Nevertheless, qualitative research has a limitation in that the subjectivity of researchers cannot be eliminated, and surveys have the disadvantage that only the items and subjects set by researchers in advance can be examined (Straka et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). Even a mixed method study of interviews and surveys was conducted (Walker et al., 2018); but ultimately, since it is a method of surveying stakeholders and items that researchers consider important in an interview, the researchers may not include all relevant matters when composing survey items presented through the interview and screening stakeholders.

Some studies have examined conflicts related to REZs using the Q methodology, which is a bridge between qualitative and quantitative research. Using the Q methodology, a survey was conducted on statements selected by the researcher through an interview to identify stakeholder groups with different perceptions and compare the differences in perceptions by group (Wolsink and Breukers et al., 2010; Díaz et al., 2017). Although the stakeholder groups that reflected regional characteristics were identified based on this, the subjectivity of researchers could not be excluded when they selected the statements, and there was also a limitation in that the type of stakeholder groups may change depending on statements.

One of the alternative techniques to overcome these limitations is text mining (Kumar and Ng, 2022). TM is a technique to understand the content and structure of dialogues by calculating the relation with main words derived from text data from dialogue sessions (Tan, 1999). Since the TM technique has the advantage of quantifying interviews, which are qualitatively delivered, and quantitatively representing them, it is actively used in various social science fields, including in the media and broadcasting. Accordingly, studies on conflicts related to renewable energy using TM were also reported (Bickel, 2017). However, many such studies have been only conducted to the extent of confirming the main words spoken by the subjects set by the researchers; they have limitations when it comes to determining the structure of interests unique to regions and proposing governance based on it.

TMS, suggested as an alternative, is a technique to identify the words spoken relatively frequently by each speaker, group stakeholders based on them, and determine key words for each group. In addition to the general stakeholder classification classified by researchers, TMS has the advantage of attempting a stakeholder classification that reflects the specific situation of regions. Furthermore, it not only is effective to seek the direction of cooperative alternatives as it enables us to identify keywords of common perception (Lee, 2021), but also facilitates the proposal of governance roles depending on the opinions of the subjects as it helps identify the subjects for each major opinion (Lee and Kim, 2021). Therefore, this study aimed to suggest a governance system for the preparation and implementation of alternatives for regional conflicts over REZs using TMS.

Research Methods

Study site

In this study, the Saemangeum FPVs project was targeted to analyze the opinions of local stakeholders in the process of energy transition using TMS. The project is South Korea’s largest renewable energy project, with a power generation capacity of 2.8 GW. However, as the project involves three local governments, conflicts arise not only between local governments, but also over whether to select separate or integrated orders. In addition, environmental pollution concerns have been raised over the fiber- reinforced plastic (FRP; a type of glass fiber) used for PV panels. As an endangered species was discovered at the FPV site, it was requested in the environmental impact assessment to modify the site (Lee et al., 2021). In this study, targeting the Saemangeum FPVs project with such diverse conflicts, the major stakeholders were interviewed and TMS was conducted with the results. Based on this, it was attempted to identify the root causes of conflicts in the region and seek cooperative alternatives (See Fig. 1 & Table 1).

Methods

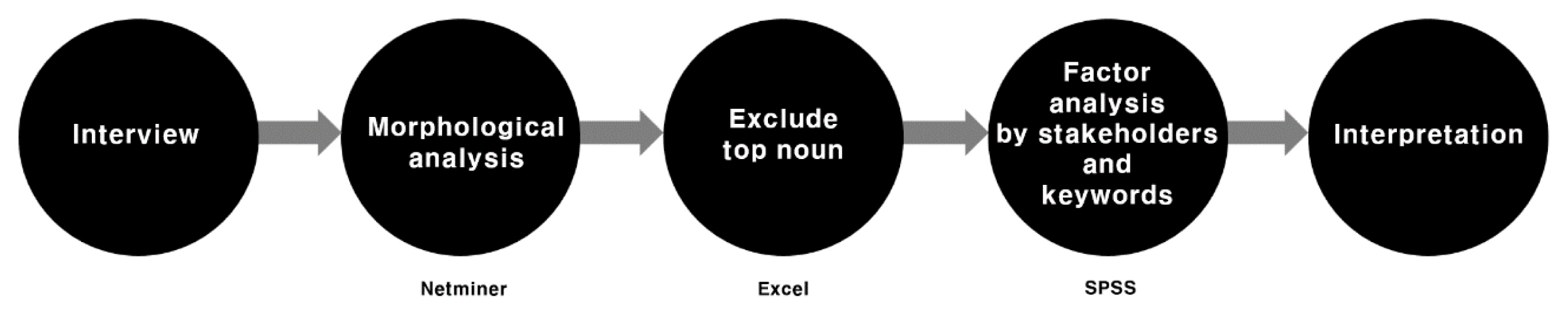

Looking at the process of TMS, the first step is to conduct an interview with the subjects. In this study, interviews were conducted with fishermen, environmental groups, public officials, experts, and business operators, centering on the 2nd-term members of the renewable energy PPC, who are major stakeholders in the conflicts over Saemangeum FPVs. A semi-structured interview was conducted on three items including current conflict issues, reasons, and alternatives, for about 1 hour per subject (Table 2).

In the second step, a morphological analysis was performed on the entire interview contents. It identified the most commonly used words in the overall interview. For the analysis, Netminer 4.3, which provides a text mining function for Korean, was used. In the third step, among the words derived by the morphological analysis, nouns with relatively high frequency were selected as the main keywords. As frequent words in TM are considered to have relatively high informational power, they are selected as the main subject of analysis (Luhn, 1958). Among such words, nouns can have meaning by themselves compared to other parts of speech, so only the top 10% of nouns with high frequency of occurrence were selected as the main keywords. In this process, major nouns were selected by comparing the number of words using Microsoft Excel. In the fourth step, a factor analysis was performed by creating a matrix for each main keyword and stakeholder after determining how many times the main keywords were used for each stakeholder. Based on this, keywords that are frequently used for each major stakeholder can be identified. In particular, since factor analysis performs the function of data standardization, it has the advantage of determining words that are spoken more frequently among them, even though many speakers spoke many words during a conversation (Bartlett, 1951; Taminiau et al., 2016). For the factor analysis, SPSS Statistics 22.0 was used. In the fifth step, the discussion structure was identified by checking the actual conversation contents based on the factor analysis results. After determining commonly used words by identifying frequently used words for each major stakeholder, the results were interpreted by understanding the context of how they were used in the actual conversation (Fig. 2).

Results and Discussion

Results of text mining for each subject

Based on the morpheme analysis, the most frequent nouns were words including development, people, landfill, seawater, and distribution. This indicates that the Saemangeum FPVs project involves the dynamics of development, nature and people (Table 3).

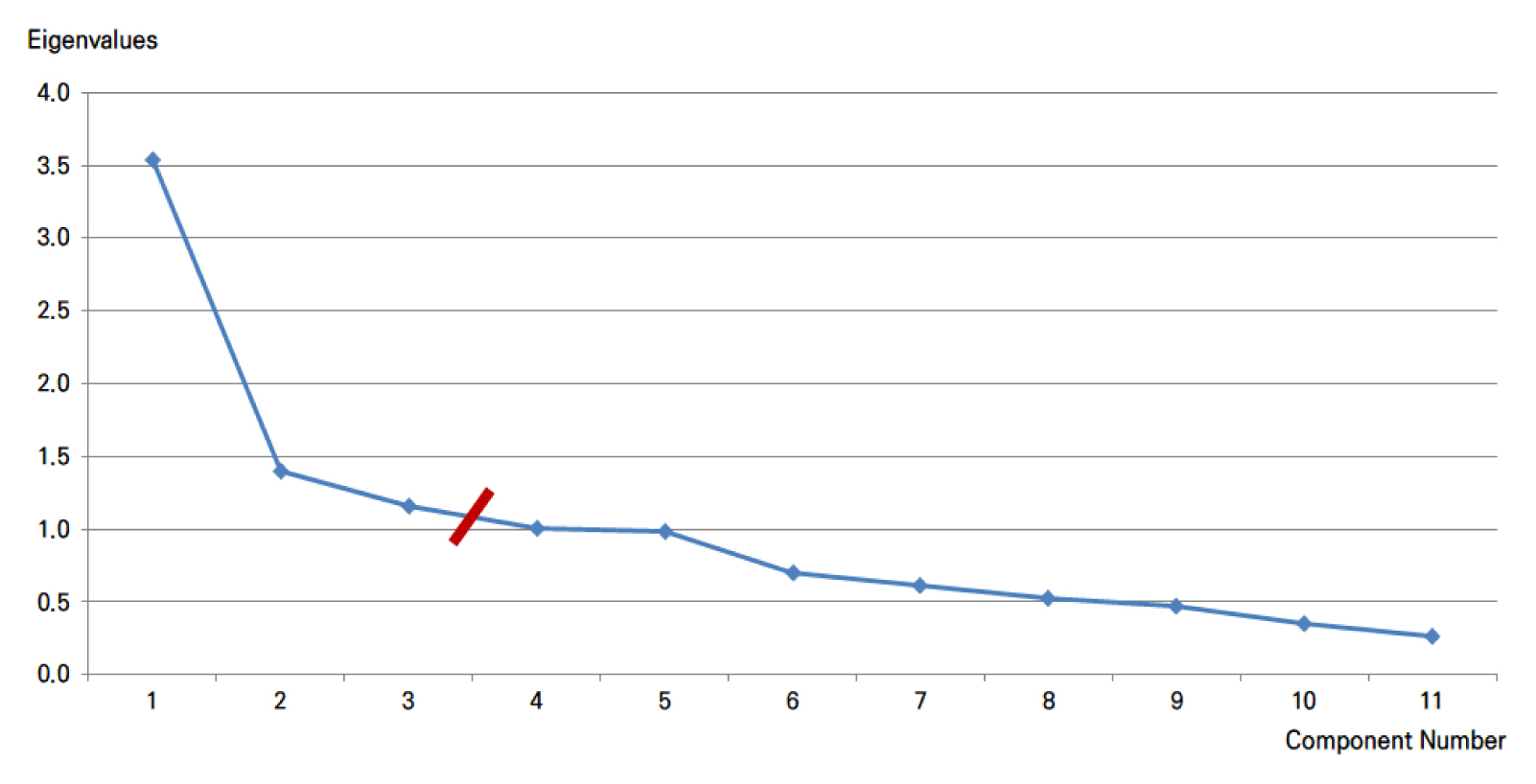

It was calculated how many times the selected keywords were used by each major stakeholder. Based on this, a matrix of utterance frequencies between stakeholders and keywords was created. Then, a factor analysis was performed focused on the stakeholders, enabling us to determine groups of the stakeholders who uttered similar words relatively more. Based on the factor analysis, 4 factors with a factor Q-sort value (Q-SV) of 1 or higher were derived, and there was little difference between factor 4 and factor 5. Considering that too many factors can hinder the simplicity of analysis, the three main factors, which correspond to the number of factors that do not sharply decrease the Q-SV, were analyzed and interpreted (Fig. 3).

The three main factors (stakeholders) derived were as follows: Factor 1, which mainly discussed development (public officials, business operators, and environmentalists in Buan); Factor 2, which mainly discussed tidal flats and seawater flow through permeable seawalls (environmentalists and fishermen in Gimje and Gunsan); and Factor 3, which discussed regional industrial transformation, including stakeholders related to industry, local governments, grid connection, and wind power (mainly PPC members including public officials, development corporations, experts, and environmental groups) (Table 4).

Factor 1 mentioned many words related to the development of renewable energy such as development, landfill, site, seawall, and wind power. Relevant local government officials, business operators, and environmentalists in Buan fell under Factor 1. They said that since the FPVs project plan has already been developed, the project could be carried out most quickly according to the plan. Local government officials and business operators seem to have this view of the need to achieve project performance quickly. Furthermore, Buan was relatively far from the FPVs project sites, so it stayed out of environmental destruction issues; it was found that environmentalists in Buan also shared such view in the context.

Factor 2 mentioned many words related to environmental conservation including tidal flats, distribution, seawater, and site. Environmentalists in Gimje and Gunsan, and fishermen from three local cities fall under Factor 2. They argued that the Saemangeum FPVs project should be based on the seawater flow through permeable seawalls. Currently, the sluice gate of the Saemangeum seawall is open twice a day for 2 hours, which helps maintain the water quality. However, they argued that the seawater flow through permeable seawalls may give movement to FPVs systems, so site selection and planning should consider this. Environmentalists and fishermen in Gimje and Gunsan seem to have made this claim because they are relatively familiar with the natural environment of Saemangeum.

Factor 3 mainly mentioned keywords related to local industries including dredging, planning, business operator, residents, industry, people, and linkage. Public officials in Buan, relevant public corporations, experts, and members of KFEM Jeonbuk fell under Factor 3. They were concerned not only over the changes the establishment of FPVs would bring to the region, but whether it could be linked to regional revitalization and job creation effects. As they expressed worries that the current FPVs plan might not be of practical help to the region, they suggested the need for a renewable energy policy that can contribute to regional revitalization. In Buan, where the data center will be built, related public corporations, experts, and urban environmental groups supported the renewable energy project, but seemed to think that the plan needs to be revised to have a positive effect on local industries.

Implication for local governance in renewable energy projects

The results of the analysis of the three factors in this study shows that the discussions by the group complying with REZ establishment according to the government-led plan that is basically understood as a green-green dilemma (Factor 1; REZ Establishment Group) and the group advocating for environmental conservation (Factor 2; Environmental Conservation Group) were expanded into those by the group advocating for regionally tailored energy transition (Factor 3; Energy Transition Group). Based on this, considering various conflict issues in Saemangeum, it seems that not only are materials and locations for FPVs that can reduce environmental pollution required, but also integrated management by relevant local governments, and project ordering methods that can have a positive effect on local industries are needed. This means that in the establishment of a regionally customized plan, the local environment and industry (Factor 2 and 3) should be sufficiently considered, while the government-led development plan (Factor 1) is carried out. This direction has been discussed in previous studies as well, and it is in line with the following studies: Attempts to find a way to build ecological REZs in the conflict between renewable energy and the ecological environment (Voigt et al., 2019; Straka et al., 2020); Efforts to find a symbiotic solution beyond conflict with existing industries including fishing and agriculture (de Groot et al., 2014; Alexander et al., 2013). However, these studies have the limitation of not determining who mainly suggested such opinions. Identification of stakeholder groups with main opinions will enable us to propose effective governance to run projects (Lee, 2021).

This study has significance in that it identified which people belong to each factor (stakeholder group). It was found that the REZ Establishment Group (Factor 1) included local public officials and environmentalists in Buan; the Environmental Conservation Group (Factor 2) included environmentalists and fishermen in Gunsan and Gimje; and the Energy Transition Group (Factor 3) included members of the public-private council (PPC). In other words, public officials sought to follow the government plan to meet their duties and conditions, fishermen demanded the preservation of the existing fishing environment, and members of the PPC debated the direction in which the renewable energy industry could aid regional development. To propose effective governance based on this, it is necessary to pay attention to the opinions of local public officials and business operators to improve the process and resolve the difficulties in the desirable implementation of the government’s renewable energy plan. To make a renewable energy plan that considers the environment, it is important to consider the perspectives of local environmentalists and fishermen who are well versed in the environmental characteristics of the region. Furthermore, to come up with measures for a fair energy transition and coexistence with the fishery, it is necessary to maintain an open mind on the opinions of the current members of the PPC.

Through this study, the role and function of PPC can be confirmed once again. The REZ Establishment Group (Factor 1) had two government sector members of the PPC of sub-regional municipalities, while the Environmental Conservation Group (Factor 2) had only one fishermen’s representative as a private sector member of the council. However, all stakeholders involved in the Energy Transition Group (Factor 3) belonged to the PPC. Compared to the civil servants of other local governments, the public officials in Buan had more learning about renewable energy, as a renewable energy theme park had been built and a related data center was also scheduled to be built. In addition, Saemangeum Development Corporation (SDCO) hoped that REZs would be well established in Saemangeum and become a means of regional revitalization; experts from local universities also argued that the participation of the local industry as private sector members of the PPC could be enhanced; and the KFEM Jeonbuk was also interested in the regional job creation effect, and wanted to reflect the regional characteristics in the project. It was found that in the Saemangeum FPVs project, the PPC played a role in debating on how to properly adapt the renewable energy project with green-green dilemmas to the region by suggesting an energy transition. In other words, the main functions to be performed by the PPC not only can include supporting the government’s planning and preparing measures to prevent environmental damage, but also can involve deriving measures such as coexistence with existing industries, conversion to the renewable energy industry, and regional revitalization (Oyewo et al., 2021; Kuriyama and Abe, 2021), In addition, impartial energy-transition experts need to participate in the PPC, and they will be able to play a role in reconciling the differences in perspective between existing industries (e.g., fishing) and new industries (wind and solar power) through various network activities.

Conclusion

A comparative analysis of the different perspectives of stakeholders on the issues of REZ sites allows us to identify the cause of conflicts, find a cooperative solution to them, and build a governance system that puts such solution into practice. In this regard, this study clarified the importance of governance organizations that can respond to problems that arise in establishing REZs by grouping opinions for each subject, and determined the need for stakeholder grouping for such purpose. An interview was conducted with the PPC for the Saemangeum FPVs project, the results of which were analyzed using text mining for each subject (TMS). A cooperative policy direction and regionally tailored governance were suggested based on the analysis results, in which this study has significance. Using the TMS presented in this study, if the opinions of various stakeholders, including the PPC, are frequently summarized and the changes are analyzed, it will aid in preventing unnecessary emotional exhaustion due to conflicts, and in deriving a cooperative alternative. Furthermore, if the main opinions for each subject are identified, ideas on how to establish a regional governance system can be obtained. In this study, TMS was used in a project site where serious conflicts had already occurred, but if it were applied at the beginning of a project, it may have the effect of preventing potential conflicts between stakeholders. It will prevent emotional exhaustion and project delays caused by conflicts, and enable regionally customized projects.

Of course, since an interview targeting the PPC for the Saemangeum FPVs project in this study was conducted with 28 participants on a one-off basis, it may have limited use as data for resolving conflicts over Saemangeum FPVs. In addition, the results for TMS might have been grasped based even on a sufficient understanding of the target site, without the analysis. Nevertheless, there seems to be no doubt that the TMs proposed in this study is a meaningful methodology; it can supplement the limitations of the Q methodology academically, provide clues for various conflicts in practice, and be used to build governance for the implementation of measures for conflict resolution. It is expected that alternatives for more effective management policies against conflicts over REZs, and directions of governance establishment will be presented in the future based on more stakeholder participation and sufficient interviews.

Notes

This study was conducted with the support of a basic research project in 2021 of the Korea Environment Institute (RE2021-02): Measures to Use Conflict Maps to Improve Resident Acceptability of Renewable Energy - Focusing on Location Planning System.