Gentrification in the Command Economy: A Story of Pyongyang Metropolitan Area in North Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Gentrification generally refers to changes in residents or operators in neighborhoods by investment in capital, a phenomenon in which wealthy or young professionals replace existing residents or operators in socioeconomic terms. Although conducted mainly in capitalist cities, some studies dealt with socialist systems or state-led gentrification. We intended to demonstrate the gentrification in North Korean by examining the cases of the socialist system and state-led gentrification and looking at urban development and urban space restructuring in Pyongyang Metropolitan Area in North Korea.

Methods

To build up methodological framework of the study, we reviewed previous literature that deals with gentrification in capitalist cities, socialist systems, and state-led planning. About the gentrification phenomenon in North Korea, we examined secondary data of North Korea refugee interviews with North Korea government documents and research papers about Pyongyang’s building and real estate development. Then, we compared gentrification in capitalist cities, socialist systems (or state-led planning), and North Korea.

Results

Gentrification in capitalist cities, socialist system and North Korea differs in their enabling conditions, gentrifying agents, gentrifiers, and processes. National and local governments, usually with the North Korea communist party, play a leading role as gentrifying agents through their public policy. In the gentrification processes, there is an increasing gap between rich and poor and spatial separation between them, especially when displaced households being pushed out of town in North Korea.

Conclusion

Urban development and apartment construction in Pyongyang shows the possibility of developing into existing gentrification, and if the private sector that leads gentrification occurs and at the same time, spatial replacement by privileged or upper classes appears, it will be clear that it is a kind of gentrification under the command economy.

Introduction

The concept of gentrification, first raised by Ruth Glass (1964), has been announced to appear in various cities around the world, but its aspects have often been subject to controversy rather than generalization (Hawkins et al., 2022; Tsang and Hsu, 2022). Nevertheless, the general definition of gentrification shared among researchers and the cases of gentrification have common features.

Gentrification generally refers to changes in residents or operators in neighborhoods by investment in capital, a phenomenon in which wealthy or young professionals replace existing residents or operators in socioeconomic terms (Lopez et al., 2022; Tsang and Hsu, 2022). As Glass (1964) emphasized, gentrification began with a positive process in which existing old and shabby houses gradually transformed into luxury dwellings after London’s working-class district was occupied by the middle class, and gradually expanded to include occupation and activity, owner-user interaction, (Nam, 2016).

Gentrification has several implications in terms of social and geographical aspects, including the transfer of low-income households to areas with low transportation and employment access (Skaburskis and Nelson, 2014) and the separation of retail from residential land use due to high land prices (Chapple and Jacobus, 2009). Gentrification is also defined as the replacement of high value-added enterprises or franchises for low value-added enterprises or small businesses (Ferm, 2016). Some scholars have also argued that there is a relationship between suburbanization and gentrification (Smith, 1996: 83).

The causes and effects of gentrification are mainly explained by political and economic discussions on the supply side (Hammel, 1999) and microscopic and behavioral discussions on the demand side (Hamnett, 1991). The supply-side study explains the causes of gentrification from a political and economic macro perspective, with the gap between capitalized and potential groundings, which also provides a reasonable rationale for the causes of gentrification due to public and private-led development and redevelopment under neoliberalism. Microscopic research on the demand side focuses on the role of human agents and the formation, thinking, and characteristics of gentrification leaders (Lees, 2000). This demand-side study attempted to clarify the reason why the middle class moved to and lived in the underdeveloped urban areas, and to understand the social, cultural, and population characteristics of gentrification in this process.

The previous studies related to gentrification were conducted mainly in capitalist cities in the West. However, some studies deal with socialist systems or state-led gentrification, which shows that the power of capital is more influential than the political system or class structure (Valiyev and Wallwork, 2019; Jolivet and Alba-Carmichael, 2021, Tsang and Hsu, 2022). Here, we probed the possibility of gentrification in the North Korean system by examining the cases of the socialist system and state-led gentrification and looking at urban development and urban space restructuring in North Korea.

To build up methodological framework of the study, we reviewed previous literature that deals with gentrification in capitalist cities, socialist systems, and state-led planning. In terms of gentrification phenomenon in North Korea, we examined secondary data of North Korea refugee interviews with North Korea government documents of construction and research papers about Pyongyang’s building and real estate development. Then, we compared gentrifications in capitalist cities, socialist systems (or state-led planning), and North Korea.

Research Methods

This study takes a methodological approach through comparison to study cities in communist countries such as North Korea. The methodological approach here is to compare capitalist cities, socialist systems, and North Korea for gentrification structures. In the case of North Korea, not only literature research but also interviews with North Korean refugees tried to increase the realism and real-time nature of the phenomenon. In the case of a comparative study, Sutherland’s conceptual model of gentrification was applied to socialist systems and North Korean cities (Sutherland, 2019).

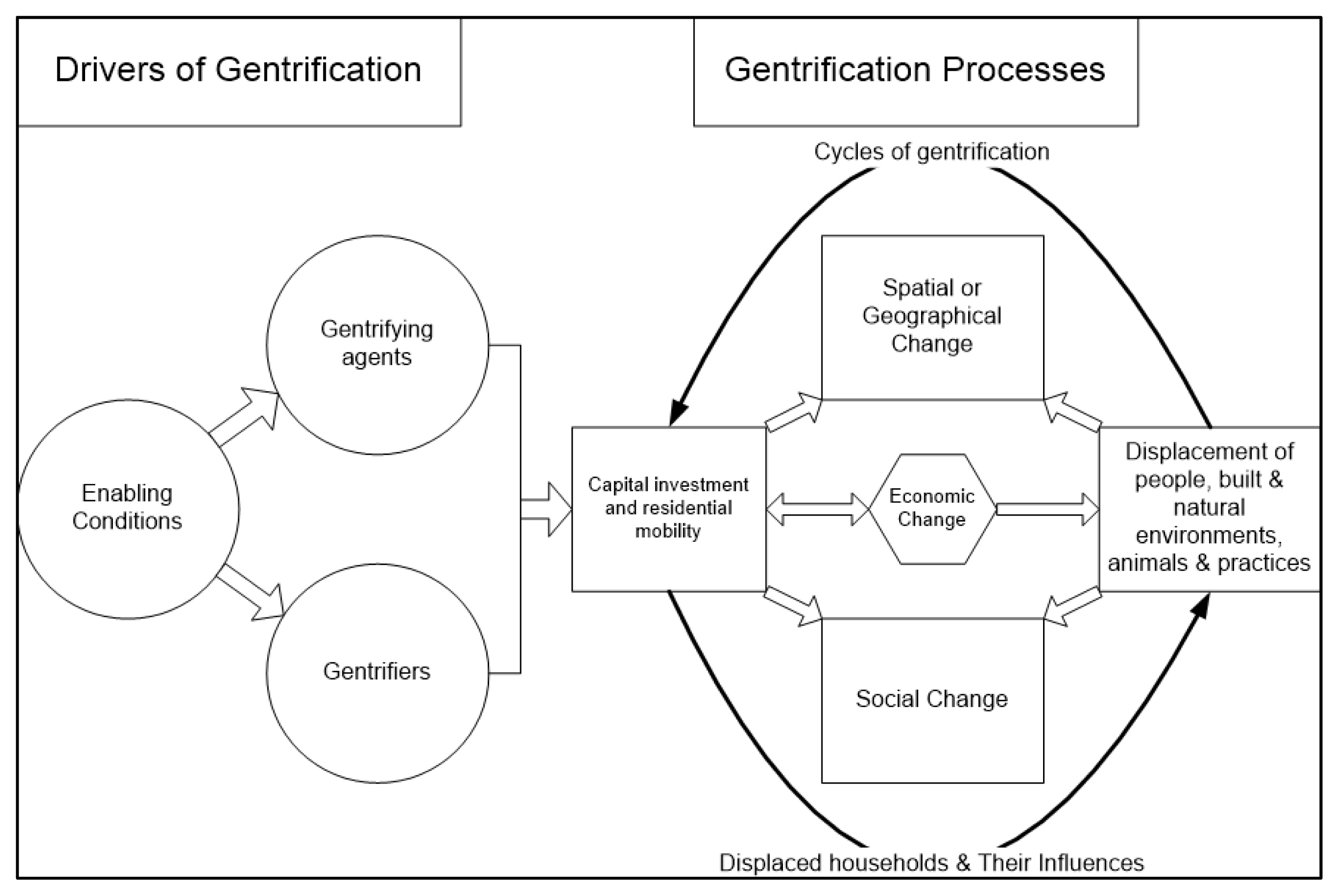

To build up methodological framework of the study, we reviewed previous literature that deals with gentrification in capitalist cities, socialist systems, and state-led planning. In terms of gentrification phenomenon in North Korea, we examined secondary data of North Korea refugee interviews with North Korea government documents of construction and research papers about Pyongyang’s building and real estate development. Then, we compared gentrifications in capitalist cities, socialist systems (or state-led planning), and North Korea. The Fig. 1 below demonstrates framework of the study, which describes a logical development the authors take to reach the conclusion of the study. In the framework, drivers of gentrification and gentrification processes are provided to assess gentrification of capitalist cities, socialist system, and North Korea cities.

A framework of the study (modified from Sutherland, 2019).

Results and Discussion

Socialist System and State-led Gentrification

As an example of socialist system and state-led gentrification, we first look at Budapest in Hungary. According to Smith (1996), Budapest’s gentrification did not begin with a plan related to the housing market, but with the global capital flow since 1989, and it was Hungary’s public policy that played a leading role. After the war, suburban expansion was led by the state in Budapest, where social housing was the focus. This focuses on solving the major housing crisis of the poor population, which in the summer of 1993, about 35% of public housing was privatized, and many of the apartments and buildings owned by the state in the past were privatized, resulting in a significant land gap. This phenomenon means that most of the essential prerequisites for Western gentrification apply to Budapest.

Gentrification in Havana, Cuba, was associated with Decree Law 288, the 2011 law that allowed Cuban citizens to buy and sell houses and own up to two houses. The case of gentrification in Havana, Cuba, comes in two forms (Jolivet and Alba-Carmichael, 2021), the first being the transfer of overseas families and self-employed citizens who have capital, replacing poor households in the city through purchases of real estate. The second form comes as Havana’s tourism economy plays an important role in several central neighborhoods, with landlords wanting to secure rooms or houses to rent to foreign tourists buying real estate for existing households. Gentrification in Havana, Cuba, is also like gentrification occurring in Western capitalist cities.

Gentrification in the Sovetsky neighborhood of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, can be said to be a national-led strategy in a socio-political context (Valiyev and Wallwork, 2019). However, Baku’s gentrification is not only explained as a result of the introduction of the market following the collapse of the Soviet Union, but it is also different from the slum district cleanup project in China. This phenomenon also has limitations in being called a post-communist growth machine by informal networks between the private and public sectors. In addition, it can be said that it is an effort to spatially redistribute socioeconomic groups and strengthen local power, led by the state, and emphasizes the creation of a comprehensive public space or urban green. In Baku, the national government commercialized space and sold land in the market in the name of exchange value. Although the landlords were not states, they formed a post-communist growth machine to weaken the state’s initiative.

State-led gentrification in Hong Kong shows a different pattern from other countries. State-led gentrification in Hong Kong appears in the form of redevelopment led by Hong Kong’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) through the Through-Town Centre (KTTC) project (Tsang and Hsu, 2022). Despite being a state-led gentrification, the project was a community-backed, community-backed process to correct environmental degradation and building obsolescence in crowded and old urban areas, and its planning reflected social goals and community aspirations. The Hong Kong Urban Development Administration tried to meet residents’ housing needs by directly engaging them in the acquisition process, and used private capital to promote redevelopment, but maintained control of the project through a plan-led approach and profit-sharing formula. In particular, the government’s continuous supply of public housing succeeded in preventing the expansion of gentrification throughout the region.

Urban Development and Urban Space Restructuring in North Korea

According to a study by Jeong (2018), in North Korea, the value of the won was depreciated due to the impact of the currency reform in 2009, and those who owned houses were relatively able to preserve it. In addition, housing prices rose, and more people participated in the real estate and housing market as demand for new homes increased due to the low housing penetration rate of 60–80 percent and the aging of homes. Since 2010, the price of imported materials from China has steadily increased, which has been reflected in the North Korean housing sale price, causing a surge in housing prices. Due to these factors, the real estate construction market begins to work in favor of suppliers because building and selling houses in North Korea can usually earn twice as much profit. Accordingly, despite high barriers to entry into the real estate and housing market in North Korea, the state, various public institutions, enterprises, individuals, and Chinese are becoming participants in housing construction.

As housing prices rise, there are cases in which apartments are built and sold to individuals, mainly by privileged institutions, or in the 2000s, institutions and businesses build houses and sell them in dollars. In this way, the authority to build apartments is transferred to institutions, but there is also a gap between institutions. For example, it is easy to build special institutions that have easy access to building materials, such as luxury companies with a lot of manpower, trade institutions that are easy to earn foreign currency, prosecutors, and Pyongyang stations, but companies that lack manpower and money, attract money to build. This makes it possible to predict that the participation of individuals and private capital in North Korea’s real estate and housing markets will increase in the future. In addition, housing supply in North Korea is led by the state, but private capital is injected into institutions and businesses in various forms, so it cannot be regarded as a national construction project.

In fact, in the 2000s, there was a boom in apartment construction in North Korea, and the main developers are state power, private capital, market, and urban bureaucrats (Hong, 2014). In North Korea, apartment construction works as a market-based mechanism, and apartments in Pyongyang will find private businesses with the right to raise funds after state agencies obtain construction permits. Therefore, there are brokers who connect state institutions and private businesses, who attract private capital, ethnic Koreans, and Chinese merchants and provide funds in kind and equipment necessary for construction. In addition, the materials needed for construction are imported from China, so they are paid in dollars, and the import rights are monopolized by a small number of organizations, including the General Bureau of Capital Construction, the Second Economy, and the People’s Security Department (Hong, 2014).

Looking at the mechanism of urban development by private capital in the market area of North Korea, institutions and businesses report the construction plan to the Cabinet’s National Construction Supervisory Service after signing an apartment construction contract with a private operator. In fact, despite the use of market capital in the process of building, it is common to count them as a national construction plan. Once approved by the Ministry of Construction and Supervision, state agencies and businesses will start construction by connecting them with the 7th General Bureau (Construction Corporation), an engineering unit under the Ministry of People’s Security, and the Capital Construction Administration (Construction Organization Control). They are the most organized institutions with the expertise of construction and manpower mobilization and can be constructed in a short period of time. Private businesses can be allocated apartment supplies from related authorities while leading construction and construction and have construction-related permits or convenience in progress.

As such, apartment construction and urban development, which have appeared in North Korea since the 2000s, show the change in urban space as the market expands. This can be seen as the gap between the rich and the poor created through the market leads to urban stratification, which is reflected in the residential space. Capitalists and powerful people mainly live in the center of the North Korean city, and low-income people mainly live outside the city, and low-income people have difficulty finding new homes because they lack capital. On the other hand, it is paradoxical that a monopoly on space occurs in North Korean cities through the collusion of private operators and government officials called Donju, and the mechanism of operation follows the logic of the market very much. In the end, lower-class people who have no money or have little connection with power are forced to be excluded from the outskirts of the city to the center of the city. Of course, it is not known exactly whether they want to move to the center of the city. Therefore, even if the form of gentrification occurring in capitalist society is not seen as it is in urban development and apartment construction in North Korea, it can be observed that the gap between the rich and the poor through the market is being fixed in urban space. In this process, lower-class people are alienated and excluded from the center of the city, and the political and economic structure to improve it is not clearly visible in North Korea’s cities and markets.

Gentrification Framework and Comparison among Capitalist Cities, Socialist System or State-led Gentrification, and North Korea Case

Gentrification in capitalist cities

Sutherland (2019) explains gentrification by dividing it into causes and processes and explains it through the following Fig. 2. This generally describes gentrification in capitalist cities, and the drivers of gentrification include land accessibility, capital circulation, and mobility of households as conditions for enabling gentrification. Under these conditions, gentrifying agents such as private developers and policy makers create opportunities for gentrification, and individuals or households seeking distinct lifestyles participate as gentrifiers. The process of gentrification is that changes in the urban landscape and social up-grade are made through capital investment and residential mobility. In this process, economic, social, and cultural capital is produced and plays a central role.

A conceptual model of gentrification in capitalist cities (modified from Sutherland, 2019).

Residents usually middle-class higher income group improve their houses. Over time if enough people act like this pushes the price of the houses up. This encourages wealthier people and developers to the area forcing the poor groups out who can’t afford the houses. This also promotes high end shops to take place at there is now a market for them. Over time the local corner shops are replaced by franchise shops and pubs are replaced by expensive bars.

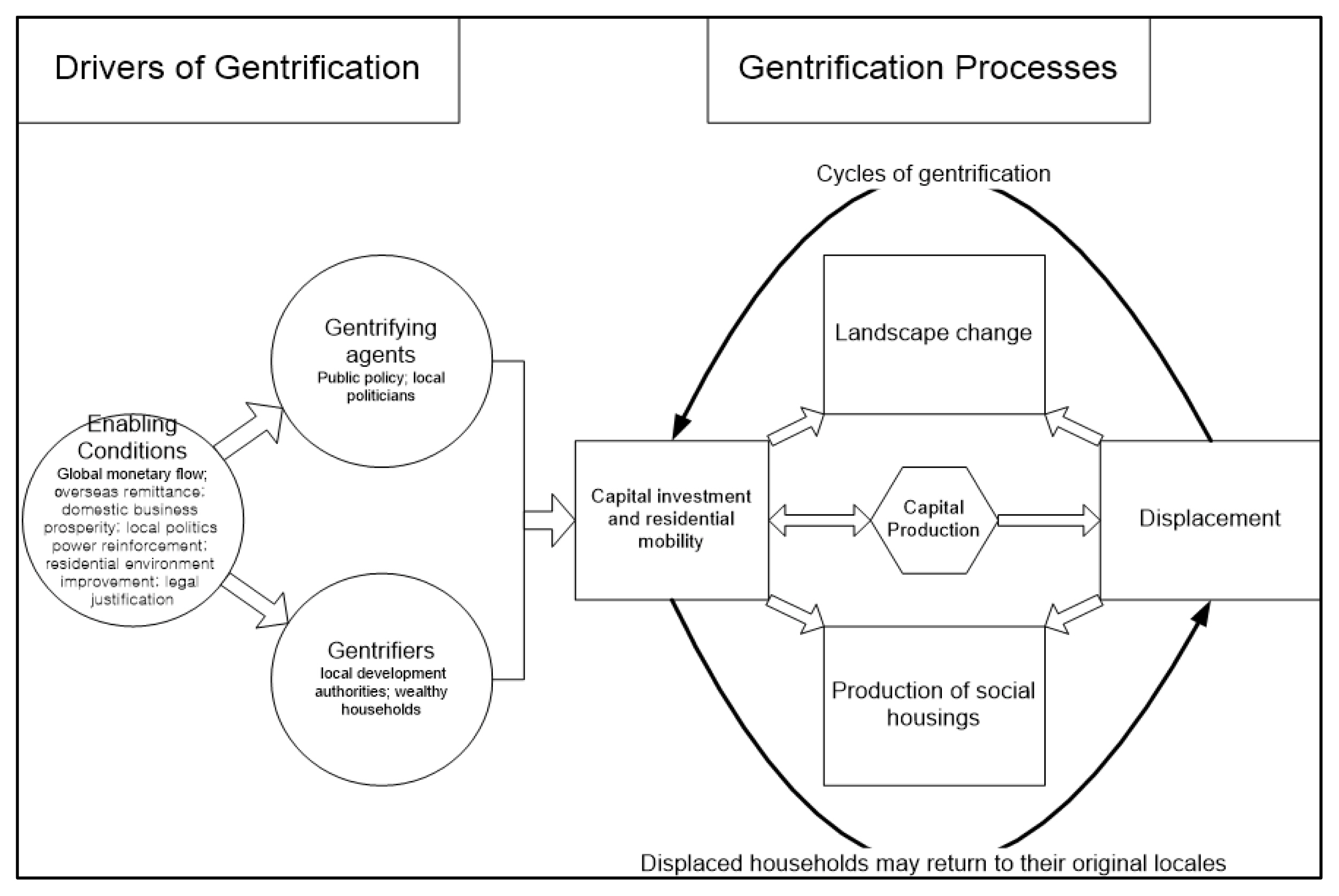

Gentrification in socialist system or state-led gentrification

Compared to gentrification in capitalist cities, that in socialist system or state-led gentrification shapes a different aspect in drivers and processes. As shown in Fig. 3 below, gentrification in socialist system or state-led gentrification is different from that in capitalist cities in terms of drivers. Global monetary flow, overseas remittance, domestic business force, local politics power reinforcement, residential environment improvement, and legal justification play an important role in enabling conditions. Local politicians play a leading role as gentrifying agents through public policy. Finally, in the case of gentrifiers, local development authorities or wealthy households appear. In terms of gentrification processes in socialist system or state-led gentrification, there is a usually mass production of public houses and displaced houses may return to their original locales.

A conceptual model of gentrification in socialist system or state-led gentrification (modified from Sutherland, 2019).

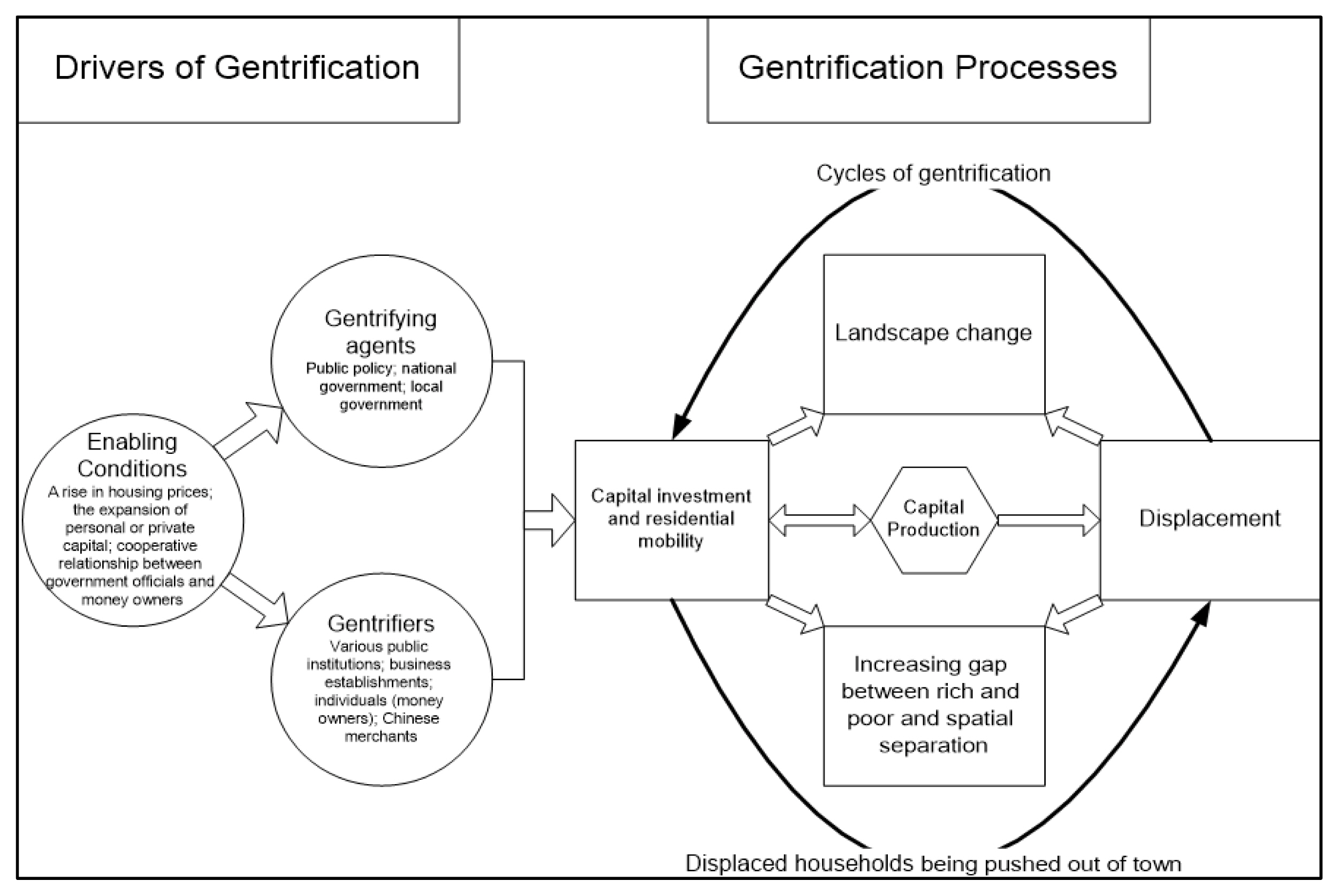

Gentrification in North Korea cities

Gentrification in North Korea shows the following differences in drivers and processes, although it does not appear in the same form as in capitalist cities or socialist systems. Fig. 4 below clearly demonstrates drivers and processes of gentrification in North Korea. A rise in housing prices, the expansion of personal or private capital, cooperative relationship between government officials and money owners play an important role in enabling conditions. National and local government, usually the North Korea communist party, play a leading role as gentrifying agents through their public policy. In the case of gentrifiers, there are various public institutions, business establishments, individuals (money owners), and Chinese merchants who are working for the gentrification in the cities. In terms of gentrification processes in North Korea cities, there is an increasing gap between rich and poor and spatial separation between them, especially when displaced households being pushed out of town.

A conceptual model of gentrification in North Korea cities (modified from Sutherland, 2019).

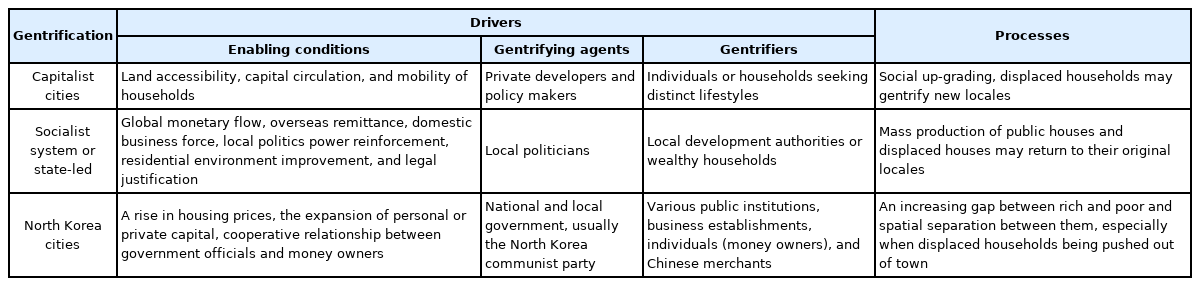

The following Table 1 clearly demonstrates major differences of gentrification among capitalist cities, socialist system, and North Korea cities. Table 1 includes drivers (enabling conditions, gentrifying agents, and gentrifiers) and processes of gentrification. Enabling conditions are in common, but there are considerable gaps of gentrifying agents, gentrifiers and processes among them. Especially the processes of gentrification show the different aspects even between socialist systems and North Korea. In the socialist systems, mass production of public houses and displaced houses may return to their original locales. In North Korea an increasing gap between rich and poor and spatial separation between them, especially when displaced households being pushed out of town.

Conclusion

In North Korea, as the market spread since the 2000s, urban development and apartment construction have increased rapidly, and private capital has played an important role, especially in large cities such as Pyongyang. Looking at the impact on institutions, developers, and residents related to the change in urban space in this process, the pattern is quite different from corporate capital in existing Western cities or gentrification led by wealthy experts.

In urban development and apartment construction in North Korea, even if private capital or individuals participate, state institutions, including the General Bureau of Capital Construction and the Ministry of People’s Security, are included in the gentrification leaders, and much of the private capital is not raised within North Korea, but foreign capital such as ethnic Koreans and Chinese. Urban development in North Korea is different from the socialist system or state-led gentrification in that they do not have explicit goals of supplying public housing, creating public spaces, or improving urban greenery or urban environment, and do not have any policies to prevent the expansion of private capital.

Nevertheless, urban development and apartment construction centered on Pyongyang in North Korea show the possibility of developing into existing gentrification, and if the private sector that leads gentrification occurs and at the same time, spatial replacement by privileged or upper classes appears, it will be clear that it is gentrification under the command economy. However, there should be more in-depth research on this, given that social and economic problems may a rise within North Korea due to such North Korean-style gentrification.

This study attempted to examine gentrification in capitalist cities, socialist cities, and above all, North Korean cities using literature research, interview data, and research models presented in previous studies. Nevertheless, there is a limit to the research in that quantitative analysis through real estate data and statistical analysis was not performed. Recalling that quantitative analysis research on gentrification is conducted through comparison of real estate prices, analysis through North Korean data is practically very difficult. However if North Korea data on building density or new development are available in the near future, gentrification in North Korean cities can be seen in more depth.

Notes

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (2021S1A 5C2A02089882).