Seniors’ Participation in Gardening Improves Nature Relatedness, Psychological Well-being, and Pro-environmental Behavioral Intentions

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Mounting evidence suggests that nature-based recreation such as gardening can generate various mental and behavioral benefits. However, the benefits of gardening for older populations are largely unknown. This study aimed to assess how a seniors’ gardening program affects older people’s nature relatedness, psychological well-being, and intent to engage in pro-environmental behavior.

Methods

We designed a one-group pretest-posttest study. Twelve seniors in their 60s and 70s participated in a gardening program occurring in a university botanical garden for 5 months. We used a 5-point Likert scale to measure the participants’ nature relatedness, psychological well-being, and pro-environmental behavioral intentions at the beginning as well as the end of the program. We compared the pretest and posttest scores on each measure using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nature relatedness and paired t-tests for psychological well-being and behavioral intentions.

Results

Our results indicated statistically significant increases in all three outcome variables after participation in the gardening program. The median score for nature relatedness was 4.167 after program participation compared to 3.500 before participation (p < .05). Also, participants’ psychological well-being mean score increased from 3.505 to 4.009 (p < .01) while their intent to engage in pro-environmental behavior mean score increased from 4.115 to 4.427 (p < .05).

Conclusion

A seniors’ gardening program can be an effective way for older people to connect with nature and improve their mental health. Also, gardening can foster the capacity of the elderly to help reduce human impacts on the environment.

Introduction

Exposure to nature has been found to restore human cognitive capacity and enhance positive emotions (Berto, 2014; Bratman et al., 2012). The psychological benefits provided by nature can be effectively attained by direct interaction with natural environments. In particular, nature-based recreation such as hiking and wildlife watching allows for first-hand experiences with nature, through which people can restore their mental capacity through sensory and cognitive stimuli. In addition, the positive outcomes from nature-based recreation can help build a connection to nature that inspires behavioral intentions to protect nature (Martin et al., 2020). Thus, outdoor activities that involve close contact with nature are increasingly gaining attention as a means to enhance human well-being and quality of life.

Despite the multiple psychological benefits provided by nature, vulnerable populations such as the elderly have limited access to nature, resulting in fewer opportunities to experience positive outcomes from nature exposure (Shores et al., 2007). The recent decline in natural areas due to urbanization puts the elderly at risk of losing the beneficial influences of nature (Kabisch et al., 2017). The marginalization of the elderly from access to nature can be addressed through organized outdoor programs specifically designed for older populations. Exposing the elderly to nature’s benefits through outdoor programs can increase the inclusivity and effectiveness of public environmental policy and education efforts.

Gardening is a nature-related activity that allows individuals to enjoy psychological and physical benefits by cultivating and harvesting plants in domesticated agriculture (Chalmin-Pui et al., 2021). Gardening is known to promote personal interest in and an understanding of the environment, as well as to encourage conservation behavior by forming connections with nature (Winkler et al., 2019). However, only a limited number of studies have explored how an organized gardening program can affect older people’s connection to nature, psychological well-being, and intent to engage in pro-environmental behavior. Examining the impacts of a seniors’ gardening program on older people’s well-being and environmentalism can highlight the role of environmental programs for underrepresented aging populations. To address this gap, this study aimed to understand how a gardening program can influence the elderly’s connection to nature, psychological well-being, and pro-environmental behavior.

Psychological benefits of nature

People experience improvements in mood and stress when they are directly or indirectly exposed to nature through activities such as forest bathing and beach driving. This phenomenon is effectively explained by the biophilia hypothesis, a belief in evolutionary psychology that humans have an innate desire to connect to nature (Kellert et al., 1993; Wilson, 2021). According to the biophilia hypothesis, humans have evolved to seek comfort and balance through contact with nature, and separation from nature can cause physical and mental deficiency (Kellert, 2003). This perspective formed the basis of Attention Restoration Theory (ART; Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989), which has been widely applied to research on the mental benefits of nature and the characteristics of the surrounding environments (Devlin, 2018).

According to ART, human cognitive activities require voluntary attention that depletes attentional capacity, and this needs to be replenished before resuming the cognitive exercise. Natural landscapes can help restore one’s attentional capacity and cognitive abilities by inducing involuntary attention (Kaplan, 1995). ART posits four environmental attributes that are essential for attention restoration: being away (i.e., psychological transport to another place), soft fascination (i.e., effortless attention drawn by soft stimuli), extent (i.e., richness and coherence that constitute another world), and compatibility (i.e., fit between desires and environmental components). A restorative environment has high levels of the four attributes that facilitate attention restoration by minimizing the need for cognitive efforts (Kaplan & Berman, 2010). For example, watching the movement of clouds or the sway of leaves in the wind requires little cognitive effort, while watching a sports event depletes attention by requiring cognitive efforts and stimulating hard fascination. Previous studies found evidence of the psychological benefits of exposure to nature such as enhanced emotional states and cognitive abilities (Bratman et al., 2015), academic achievement (Benfield et al., 2015), and environmental attitudes and behavior (Whitburn et al., 2019).

The benefits of contact with nature can be obtained not only in wild nature but also through nature-based leisure activities such as gardening. Scott et al. (2015) found that gardening activities can improve connections with nature, appreciation of aesthetic values, and the physical and mental well-being of older Australian gardeners. Soga et al.’s (2017) meta-analysis found that gardening can provide a wide range of benefits in areas such as physical health, life satisfaction, quality of life, and an increased sense of community. Chalmin-pui et al. (2021) found that greater participation in gardening resulted in better mental well-being and physical activity as well as lower stress levels among UK gardeners. In South Korea, Park and Huang (2010) reported that the horticultural leisure program positively affected the psychological well-being, depression, and life satisfaction of the elderly in rural areas. In addition, Kim (2010) found that elderly women’s depression level was reduced after participation in horticultural activities, while Park et al. (2015) found horticultural therapy to be more effective than forest therapy in reducing depression. Therefore, gardening as a leisure activity has great potential for providing nature’s therapeutic benefits in daily lives.

Connection to nature

The concept of connection to nature refers to the association of an individual with other species and natural environments in affective, cognitive, and experiential aspects (Restall and Conrad, 2015). Connection to nature can explain humans’ inherent tendency to approach and feel intimacy toward nature. This psychological construct has gained increasing attention in the field of environmental psychology since the early 2000s. Researchers have measured connection to nature using various concepts such as emotional affinity with nature (Kals et al., 1999), the inclusion of nature in self (Sultz, 2002), connectedness with nature (Mayer and Frantz, 2004), and nature relatedness (Nisbet et al., 2009). Among them, the measure of nature relatedness has relatively strong theoretical and statistical stability, and has been applied to various populations, including children and adults (Salazar et al., 2020).

Gardening provides experiences with nature through sensory contact with plants and related living organisms in the biome, which can promote individuals’ connection to nature. Shaw et al. (2013) found that urban gardening activities in an Australian city increased participants’ levels of connection to nature. In addition, Suto et al. (2021) qualitatively analyzed 23 Canadian adults participating in regional gardening activities and found that gardening enhances a sense of connection to other living things as well as positive emotions. Not only is connection to nature an outcome of gardening, but individual demand for it can also motivate participation in gardening (Eger et al., 2018). Therefore, gardening can form a virtuous cycle driven by the beneficial outcomes from nature and human desires for interaction with nature.

Psychological well-being

In the field of positive psychology, human happiness has been understood in terms of hedonic aspects such as life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985) or positive emotion (Watson et al., 1988) and eudaimonic concepts such as psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989). Psychological well-being refers to the aggregate of psychological factors that constitute and influence an individual’s life and function as a criterion for the quality of life (Veenhoven, 1991). A high level of psychological well-being represents positive human functioning driven by goals and meanings in life (Ryff, 1989). The six core dimensions of psychological well-being are self-acceptance, autonomy, environmental mastery, positive relationships with others, purpose in life, and personal growth. Psychological well-being is determined by a long-term life course rather than short-term and specific situations (Ryff and Keyes, 1995).

Prior studies reported positive associations between psychological well-being and nature-based activities. For example, a positive correlation was found between nature-based recreation activities and the psychological well-being of adults (Wolsko et al., 2019). Jean and Lee (2012) reported that the elderly’s psychological well-being improved after walking exercises. Kim and Kim (2013) argued that promoting psychological well-being plays a vital role in improving the life quality of middle-aged and older people. In addition, horticultural activities improved the psychological well-being of elderly women (Hassan et al., 2018). As such, nature-based activities play a significant role in improving one’s psychological well-being, which in turn can promote overall happiness in life.

Pro-environmental behavior

Pro-environmental behavior is conceptualized as behavior that minimizes human impact on the environment or even improves its quality based on the awareness of environmental problems (Steg and Vlek, 2009). Active pro-environmental behaviors such as using public transportation and planting trees can contribute to personal health as well as environmental conservation (Rosa and Collado, 2020). Intentions to engage in pro-environmental behavior are influenced by external factors such as other people’s judgment or regulations, as well as by internal forces including personal values and norms (Steg et al., 2014; Stern et al., 1999). Also, the amount of contact with nature and experiences in nature is positively related to pro-environmental behavioral intentions (Kim, 2002), and connection to nature formed by exposure to nature can encourage behaviors to protect nature (Whitburn et al., 2020). This relationship was also found in a positive correlation between people’s participation in nature-based leisure activities and pro-environmental attitudes (Cooper et al., 2015). These findings support the role and necessity of nature-based recreation in encouraging people’s engagement in pro-environmental behavior.

Survey studies often measure pro-environmental behavior using self-reported items to understand the frequency or intensity of engagement in behavior over a certain period of time in the past, or the strengths of intentions to engage in behavior in the near future (Lange and Dewitte, 2019). Participation of different populations in certain types of pro-environmental behavior may differ due to diverse socio-cultural settings and demographic characteristics (Poortinga et al., 2004). For example, using public transportation instead of a personal vehicle is more feasible in urban settings than in rural areas. Therefore, considering the situational and contextual factors that affect behavioral decisions (Steg et al., 2014), it is important for a survey study to use pro-environmental behavior items relevant to a study population.

The present study

There is increasing evidence of nature-based activities’ positive effects on mental health, quality of life, environmental attitudes, and community consciousness among a range of populations (Hawkins et al., 2011; Wang and MacMillan, 2018; Nicholas et al., 2019). However, the effects of gardening on the elderly’s mental well-being and environmentalism are largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a seniors’ gardening program on the elderly’s nature relatedness, psychological well-being, and intentions to engage in pro-environmental behavior. We expected the findings to advance our understanding of the practical implications of gardening programs for socially vulnerable populations such as the elderly.

Research Methods

Study design and hypothesis

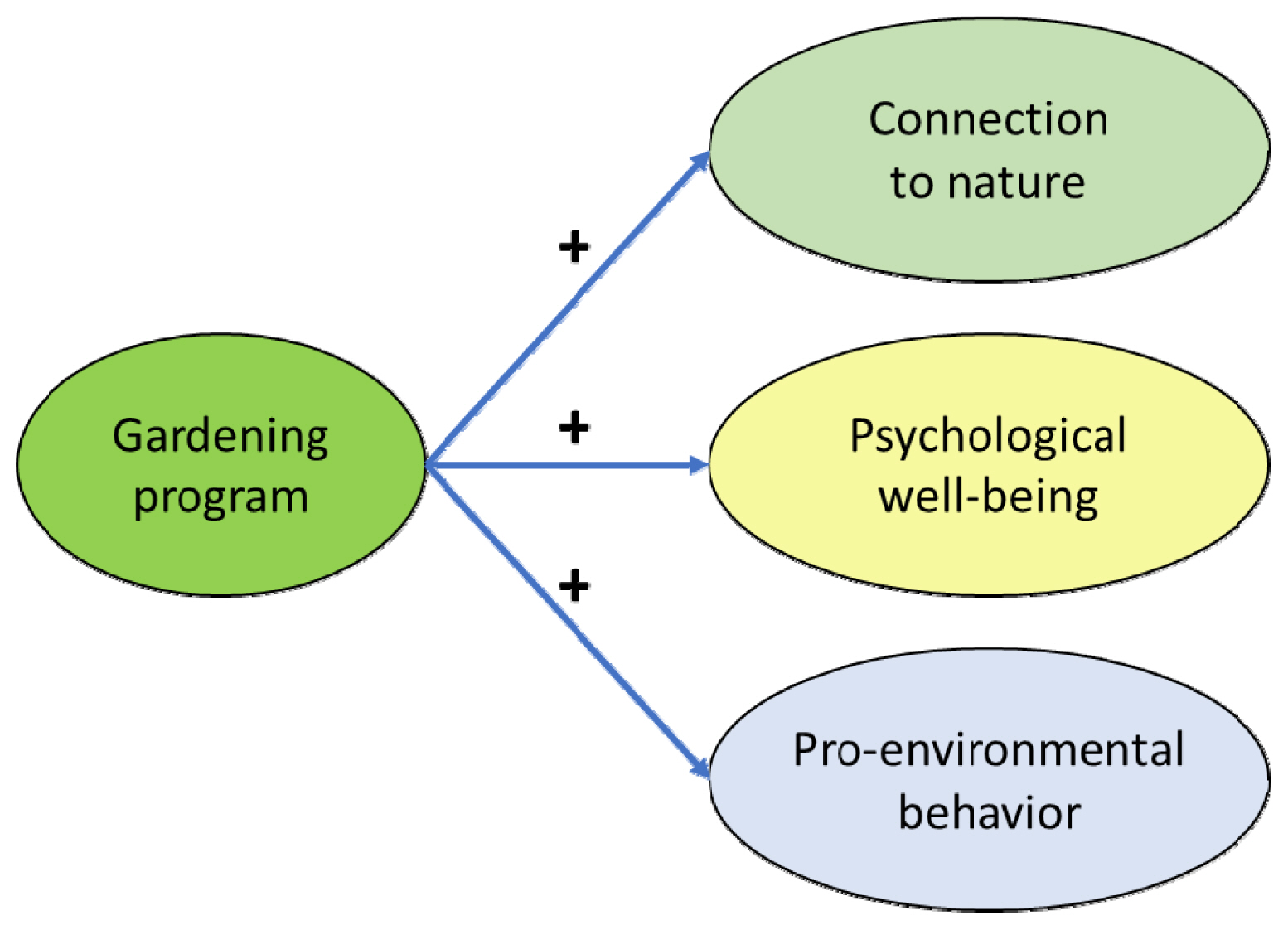

The study employed a one-group pretest-posttest design. Fig. 1 shows the hypothesized relationships among study variables. Based on prior theoretical and empirical evidence from the literature, gardening activities were expected to positively affect participants’ connection to nature, psychological well-being, and pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Accordingly, the research hypotheses were as follows:

Hypothesized effects of a gardening program on participants’ connection to nature, psychological well-being, and pro-environmental behavior.

Participants’ connection to nature scores measured after the gardening program will be significantly higher than before the program.

Participants’ psychological well-being scores measured after the gardening program will be significantly higher than before the program.

Participants’ intentions to engage in pro-environmental behavior scores measured after the gardening program will be significantly higher than before the program.

Study site

The study was conducted at Wonkwang University’s Natural Botanical Garden in Iksan, Jeollabuk-do (Fig. 2). Wonkwang University’s Natural Botanical Garden has a geographic location of 126° 45′ east longitude and 35° 50′ north latitude, 10–20 m above sea level, an annual average

Wonkwang university botanical garden (a: main gate of the botanical garden, b: botanical garden aerial photograph, c: making a garden 1, d: making a garden 2).

temperature of 13.3°C, and annual average precipitation of 1,280mm. The natural botanical garden contains about 2,000 species of plants in 150 families and 430 genera. It also features thematic gardens such as a wetland, a rockery, and a topiary.

Study participants

Study participants were recruited from the Dementia Relief Center in collaboration with the local public health centers in Iksan. We invited seniors with no mental or physical health issues to participate in the study. A total of 23 seniors from age 63 to 87 living in Iksan volunteered to participate in the gardening program implemented by the National Arboretum and agreed to participate in the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was conducted with the consent of the participants.

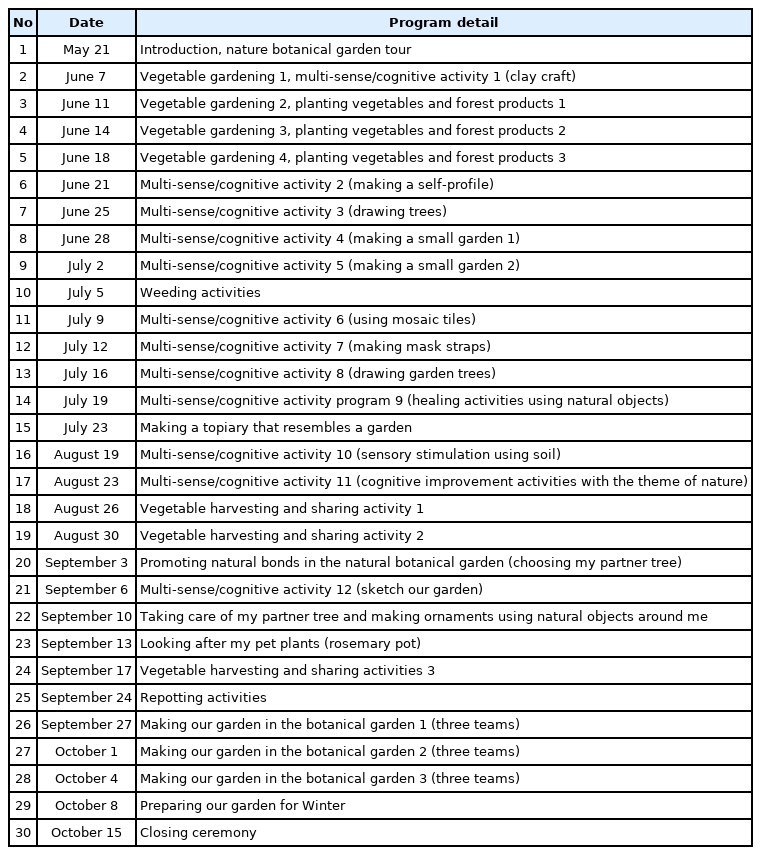

Survey results from 12 participants who attended all sessions were included in the study. Four (33.3%) of them were male, and 8 (66.6%) of them were female. The average age of the participants was 69.6 years. The program participants engaged in organized activities twice a week from May 21 to October 15, 2021 (Table 1). The program activities occurred mostly outdoors, but an indoor program was provided in the event of inclement weather such as rain and high temperatures.

Data collection

The research team led the implementation of the program while trained research assistants aided in data collection using survey questionnaires. In the in-person survey, research assistants orally delivered the survey items and recorded participants’ responses. The survey was administered at the beginning (June 7) and at the end of the program (October 8), and each survey took approximately 15 minutes.

Survey measures

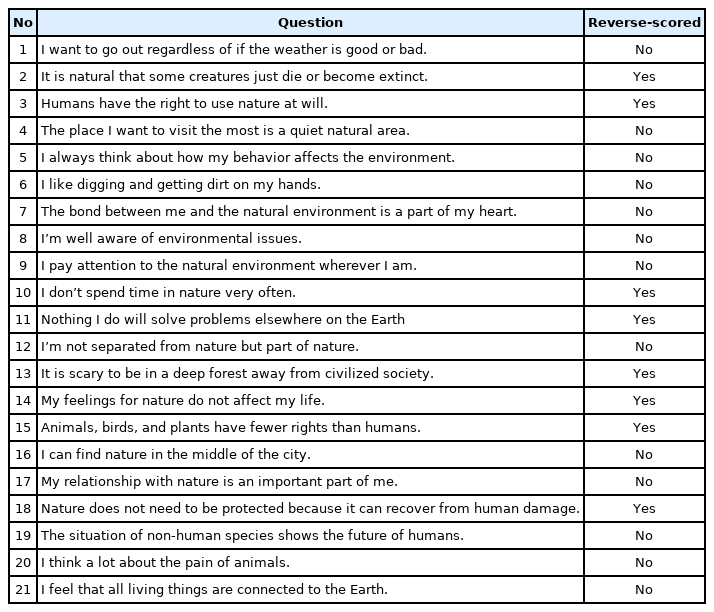

To measure participants’ connection to nature, we used the 21-Item Nature Relatedness (NR) Scale (Nisbet et al., 2009) translated into Korean and adapted to the study context (Table 2). Each item was measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items include "I want to go out regardless of if the weather is good or bad," "The place I want to visit the most is a quiet natural area" and "I feel that all living things are connected to the Earth."

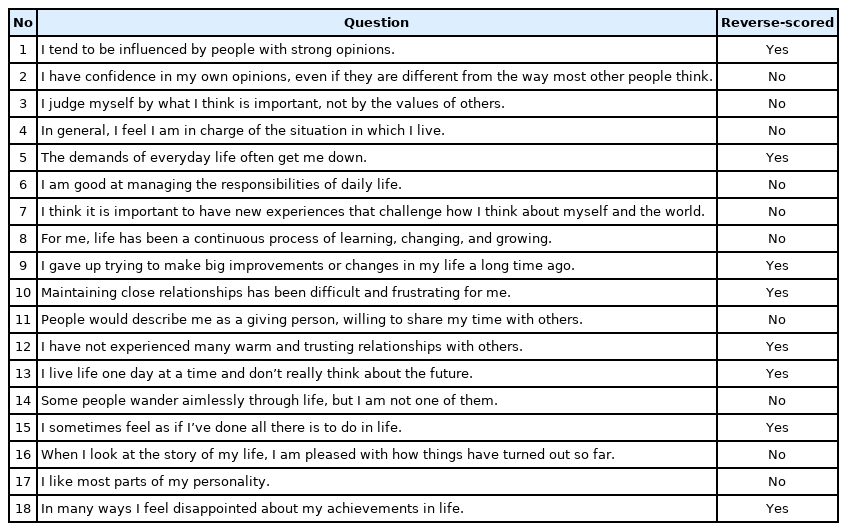

Psychological well-being was measured with the Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS) developed by Ryff (1989) and translated into Korean. The original scale consisted of 120 items (20 items for each sub-category) (Ryff, 1989), but we adapted the short version (18 items) developed by Ryff and Keyes (1995) (Table 3) to reduce the cognitive burden on respondents. Each item was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items are "I judge myself by what I think is important, not by the values of others (autonomy)," "I gave up trying to make big improvements or changes in my life a long time ago (personal growth)" and "I like most parts of my personality (self-acceptance)."

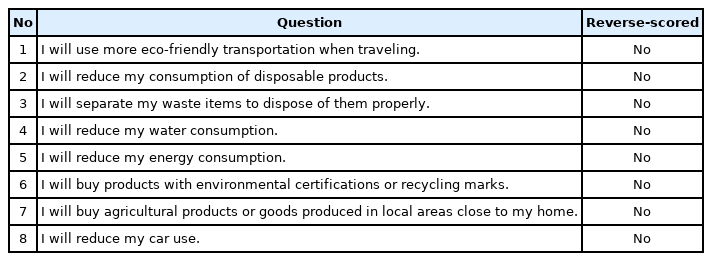

We measured participants’ self-reported intentions to engage in pro-environmental behavior using eight items (Table 4) developed in a prior study to measure the general pro-environmental behavior of Korean citizens (Ahn et al., 2021). Each item was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items are "I will use more eco-friendly transportation when traveling," "I will buy products with environmental certifications or recycling marks" and "I will buy agricultural products or goods produced in local areas close to my home."

Analysis

Participants’ responses to the items on connection to nature, psychological well-being, and intentions to engage in pro-environmental behavior were analyzed using one-tailed tests because we hypothesized the positive effects of all independent variables. We determined the appropriate analytical method for each variable following the decision-making tree shown in Fig. 3. We used Shapiro-Wilk’s normality test for each variable to determine the normality of data, and decided to use a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nature

relatedness because its scores were not normally distributed. For psychological well-being and pro-environmental behavioral intentions, the normality of the data was satisfied, so a paired sample t-test was used for each variable. R Studio was utilized for the statistical analysis.

Results and Discussion

Participants’ nature relatedness, psychological well-being, and pro-environmental behavioral intentions scores measured after the gardening program were found to be significantly higher than the scores before the program (Table 5).

Gardening program’s impact on nature relatedness

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that nature relatedness measured after the gardening program (Md = 4.167) was higher than the initial level (Md = 3.500), which was statistically significant (p < .05). This suggests that the gardening program provided a range of activities that build psychological connections between the participants and nature, likely through providing sensory stimuli as well as cognitive input. Indeed, the gardening program included activities specifically designed to promote the physical and psychological abilities of the elderly, which might have worked in favor of the affective and cognitive aspects of connection to nature. This finding is in line with prior studies that reported that a gardening program helped cultivate a sense of connection to nature and positive emotions in adults (Suto et al., 2021) and in Australian seniors (Scott et al., 2015). Our finding provides additional empirical evidence that a gardening program for seniors can improve older people’s connection to nature.

Gardening program’s impact on psychological well-being

The average psychological well-being of participants was 3.505 before program participation and 4.009 after participation, an increase of 0.504. This difference was found to be significant (p < .001). Therefore, we found evidence that a gardening program for seniors can improve the psychological well-being of elderly people. This process can be explained by the positive effects of nature exposure on eudaimonic well-being. Previous research found that frequency of nature visits and proximity to natural spaces are positively associated with eudaimonic aspects of happiness, such as the meaningfulness of life and feelings of elevation (Passmore & Howell, 2014; White et al., 2017). The gardening program for seniors in our study allowed for ample exposure to nature and human-nature interactions, which might have led to an increase in the psychological well-being of participants. This relationship has also been found in other nature-based programs, such as forest education programs for adolescents (Cho et al., 2014). Our results suggest that five months of gardening activities in botanical gardens can enhance the psychological well-being of the elderly.

Gardening program’s impact on pro-environmental behavior

The average score of pro-environmental behavioral intentions was 4.115 before participation in the program and 4.427 after participation, an increase of 0.313. This difference was statistically significant (p < .05). As expected, the gardening program increased participants’ willingness to engage in behaviors that minimize human impacts on the environment. This result may be attributed to the program’s emphasis on appreciation of nature and care for nature through hands-on activities with plants and natural materials for crafting. Not only could the cognitive input have improved participants’ environmental awareness and perceptions, but the affective connection with nature could also have contributed to their willingness to protect the environment. Thus, gardening may encourage pro-environmental behavior by fostering a strong human-nature relationship that motivates intentions to engage in conservation actions. Previous studies have also shown the behavioral benefits of nature-based programs. Jin (2019) found that nature-based activities including ecological-cultural experiences positively affected individuals’ pro-environmental behavior. Also, Mackay and Schmitt (2019) reported that a high sense of natural connection promoted pro-environmental behavioral intention. Therefore, different types of nature-based interventions can be used to promote pro-environmental behavior in various populations.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of a 5-month gardening program for seniors on elderly participants’ nature relatedness, psychological well-being, and intent to engage in pro-environmental behavior. We found positive effects of the program on the study variables, which provides evidence that nature-based programs can contribute to building a sustainable society by promoting the mental well-being and environmentalism of the elderly.

The study has the following limitations. First, although our study results agree with previous findings, it is important to note that the results were derived from 12 participants and thus are non-generalizable. Moreover, qualitative methods can be employed to explore the meanings of gardening activities to older people and how they can foster connection to nature and mental well-being. Second, this study was conducted in a pretest-posttest design without a control group. This single-group design study is not robust to the time difference, so the actual effectiveness of gardening may lack generalizability.

Despite these limitations, this study targeted seniors in vulnerable classes to investigate the positive effect of gardening on their specific psychological factors (connection to nature and psychological well-being) and pro-environmental behavioral intentions. The study has implications in terms of recognizing the value of a nature-based recreation program for the elderly.

Notes

This study was supported by the 2021 research fund from Wonkwang University