|

|

- Search

| J. People Plants Environ > Volume 24(2); 2021 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background and objective: Instagram, an image-based social media, is being used as an important outlet for the communication and place marketing of public spaces. The purpose of this paper was to analyze how types of place-based content affect user reactions (Likes and Comments) on Instagram in order to provide basic data on the operation and utilization of social media by public places such as botanical gardens and arboretums.

Methods: A total of 850 posts uploaded to the Instagram account of Kew Gardens from November 6, 2014 to July 3, 2020 were classified using 14 subject codes. Multiple regression analysis was performed to evaluate the userŌĆÖs reaction between the dependent variables (ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ, ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ) and the independent variables (14 subject codes).

Results: The findings showed that user reactions appear to differ depending on the typology of the content, and ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ were presented in independent behavioral reactions. In particular, ŌĆ£close-ups of plants (botanic, macro),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£plant colony (botanic, wide),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£place-specific landscape (building, landscape),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£anniversaryŌĆØ and ŌĆ£informationŌĆØ showed positive impacts on both ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ which could lead to electronic word-of-mouth and content sharing.

Conclusion: Based on these findings, it can be argued that the typology of a botanical gardenŌĆÖs content can be used to determine factors that affect the immediate reactions and enhance engagement with users.

Methods: A total of 850 posts uploaded to the Instagram account of Kew Gardens from November 6, 2014 to July 3, 2020 were classified using 14 subject codes. Multiple regression analysis was performed to evaluate the userŌĆÖs reaction between the dependent variables (ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ, ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ) and the independent variables (14 subject codes).

Results: The findings showed that user reactions appear to differ depending on the typology of the content, and ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ were presented in independent behavioral reactions. In particular, ŌĆ£close-ups of plants (botanic, macro),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£plant colony (botanic, wide),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£place-specific landscape (building, landscape),ŌĆØ ŌĆ£anniversaryŌĆØ and ŌĆ£informationŌĆØ showed positive impacts on both ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ which could lead to electronic word-of-mouth and content sharing.

Conclusion: Based on these findings, it can be argued that the typology of a botanical gardenŌĆÖs content can be used to determine factors that affect the immediate reactions and enhance engagement with users.

South Korea has 35.5 million social media users, 87% of its population, which is about 1.8 times the global average (49%). More specifically, Instagram has 11.49 million monthly active users (MAU) in South Korea as of June 2020, and it has also been reported that both the number of users and the average time spent per person have seen a sharp increase (DMC Media, 2020). With the development of smart devices, social media is actively being utilized as a new tool for place marketing, experiences and communication in online spaces are delivered in the form of images and text through the visual sense (Seo et al., 2020), and thus playing an important role in forming place images. Web 2.0-based social media is characterized by features such as participation, openness, conversation, community, and connectedness (FKII, 2006). As such media enables real-time connectivity and interaction with virtually no time and place constraints, the participants can communicate much more easily and directly. Accordingly, social media is being recognized as an important communication media by public institutions, and actively used to build a positive local image through place branding.

Instagram is a social networking service (SNS) officially launched in the United States in 2010 that is tailored for mobile devices, and is characterized by featuring images as the main content rather than text (Kim, 2016; Park and Oh, 2019). It is a representative third-generation SNS that allows users to express their feelings and interact with other users by posting a post with a simple hashtag when they shoot an image that they want to share with their smart device, or upload an existing image (Nam et al., 2015). Beyond just sharing photos, the service enables creative expression, allowing users to communicate and form communities through storytelling about images and interacting with usersŌĆÖ responses. On Instagram, users can follow and view the accounts they are interested in, and post user-generated content to followers to elicit immediate and intuitive reactions from them, such as ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ or ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ compared to previous social networking services (SNSs), which were dominated by text-oriented content, Instagram can quickly accommodate and spread a vast amount of information by allowing the production and sharing of visual images through photos and videos. In addition, through the service, users can search for content on a specific topic by using hashtags that provide the function of binding and cross-referencing related visual images. This enables users to follow a ŌĆ£hashtagŌĆØ for a specific topic, enhancing the ease and scalability of information retrieval, and improving the connectivity between contents (Lee et al., 2019).

Previous studies using social media data such as Instagram performed data and text mining for the purpose of big data analytics, where text analysis was mainly focused on aspects such as sentiment analysis of hashtags, location information analysis of specific place tags, and image type analysis. Looking at the research trends related to Instagram data, Kim et al. (2019) utilized InstagramŌĆÖs big data to determine the potential and importance of Instagram as a new tool in the field of regional survey and analysis as well as a data source from the perspective of urban users. Shin et al. (2020) analyzed the original news text with a data mining technique using big data to understand how the publicŌĆÖs interest in arboretums and botanical gardens has changed socially, economically, and culturally according to the trend of the times. Seo et al. (2020) investigated how information about the Seoul Botanic Park is shared and propagated on the online system, and how recipients of such information perceive it, and reported that spatial information online is delivered in various types of text through social networking services (SNS) that enable users to communicate, rather than unilaterally through the official website. Kim et al. (2019) suggested that SNS data provide important information in establishing the direction of park design and management in an effective manner by serving as the basis for the real-time monitoring of park usage patterns and satisfaction factors.

Although research has been conducted on the content types of public institutions and user interactions exposed through social media including Twitter and Facebook (Kim, 2015), the classification of the types is broad; studies that can be applied to specific public places such as botanical gardens are currently lacking. Since social media management has not yet truly been introduced to most public institutions in Korea, particularly in botanical gardens, arboretums, and national and public parks, with the exception of National Baekdudaegan Arboretum, it is urgent to establish social media utilization strategies for public institutions. Therefore, this study was conducted to provide basic data on social media utilization and operation plans in public places, particularly national and public parks and botanical gardens, by analyzing usersŌĆÖ reactions to the different types of social media contents.

The official name of Kew Gardens is Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, though it is usually called Kew Gardens. It is the first landscape garden that stretches about 120 hectares between Richmond and Kew in southwest London, and includes a number of large greenhouses, themed gardens and buildings. It is one of the oldest botanical gardens in Europe, with a history that spans more than 250 years, and was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003. In addition to the regular botanical garden program, Kew Gardens has recently been running a program that places a great emphasis on environmental education and conservation of nature. It operates a variety of communication channels such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, as well as its official website. Kew GardensŌĆÖ Instagram account made its first posting on November 6, 2014, and it has made a total of 898 posts thus far (as of October 2020). It follows 203 accounts, and has 413,000 followers (Table 1). Through sharing the plants and landscapes of Kew Gardens on Instagram, where images are the focus rather than explanations, it not only spreads information, but also forms an interaction between the botanical garden and followers.

This study collected the first 850 image posts made by the Instagram account of Kew Gardens (@kewgardens), a representative botanical garden in the UK, from November 6, 2014 (the first posting date) to July 3, 2020. To analyze the data collected by type based on the 14 content types established through a review of the literature, and to test the statistical significance of the regression coefficient for each independent variable based on a significance level of 0.01 regarding the correlation between the place-based content type and the structure of two user reactions, ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ, a multiple regression analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0, a statistical analysis software package (Fig. 1).

The typology of physical environments that constitute a ŌĆ£placeŌĆØ that directly forms a public space, and that of non-physical elements such as activities, will vary depending on the research purpose and the scope of the research site (Lee. 2019). In a previous study on public space patterns, Seo and Lim (2016) classified urban public space patterns for place identity into four types: culture and leisure- oriented, community-centered, art and design-based, and technology-embedded; Hong (2012) categorized such space pattern into four types: natural, historical, artistic, and commercial. In this study, the categorization was refined into types suitable for botanical garden contents, based on the 23 subject types of Sevin (2013), which classified the types of place-based contents on social media in the broadest range, including arts, attractions, business, characteristics, culinary, events, freebies/deals, history, local tips, lodging, movies, museums, nature, nearby information, no identifiable subject, parks, people, policies of places, sports, travel, Twitter-related, welcome (welcoming words to visitors), and other. According to Holsti (1969), analysis categories should meet five distinct requirements for classification criteria that they should reflect the research purposes, be mutually exclusive, be exhaustive, be independent, and be based on a single classification principle. Therefore, in this study, analysis categories were established based on the content typology developed for previous studies within the scope of satisfying these requirements.

To classify content types suitable for public places specified as botanical gardens, a preliminary study was conducted by selecting three botanical garden accounts on Instagram. Based on the study, a total of 14 types of content were derived, including images of animals; close-ups of plants (botanic, macro); plant colonies (botanic, wide); place-specific buildings (building, alone); place-specific landscapes (building, landscape); anniversaries; (various) information; exhibitions; photos of people working; recipe; book publishing; visitors; reposts and research (Table 2). The exposure status of each of these 14 content types was investigated, and a multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between the content type and the structure of the two possible user reactions, ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Comments.ŌĆØ

Two researchers worked to perform classification based on the 14 types of contents established through the preliminary study. First, according to the definition of each independent variable, for each of the 14 variables, content that met the definition was coded as ŌĆ£1ŌĆØ while content that did not was coded as ŌĆ£0ŌĆØ as follows: for animal content type, content containing animals was coded as ŌĆ£1ŌĆØ and content that did not was coded as ŌĆ£0ŌĆØ; for plant close-up content type, content containing close-ups of plants was coded as ŌĆ£1ŌĆØ and content that did not was coded as ŌĆ£0ŌĆØ; for plant colony content type, content containing a plant colony was coded as ŌĆ£1ŌĆØ and content that did not was coded as ŌĆ£0ŌĆØ; for the place-specific landscape type, content containing the landscape of facilities or buildings in the botanical garden was coded as ŌĆ£1ŌĆØ and content that did not was coded as ŌĆ£0ŌĆØ The coding definition of each variable is shown in Table 3.

After coding the contents that were classified, the images in which the sub-items belonging to each category did not match were re-coded through mutual consultation. In terms of ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ based on a previous study that found SNS users decide whether and when to comment depending on the amount of information they wish to share on the SNS (Ariel and Avidar, 2015), comments were analyzed by simply targeting the number of comments regardless of whether such comments are negative or positive, and applying natural logarithms to each type of ŌĆ£LikeŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentŌĆØ to control the influence of the measurement unit. To overcome the subjective bias problem of coders, inter-coder reliability was investigated using HolstiŌĆÖs method (1969), and the reliability coefficient was confirmed (Table 4).

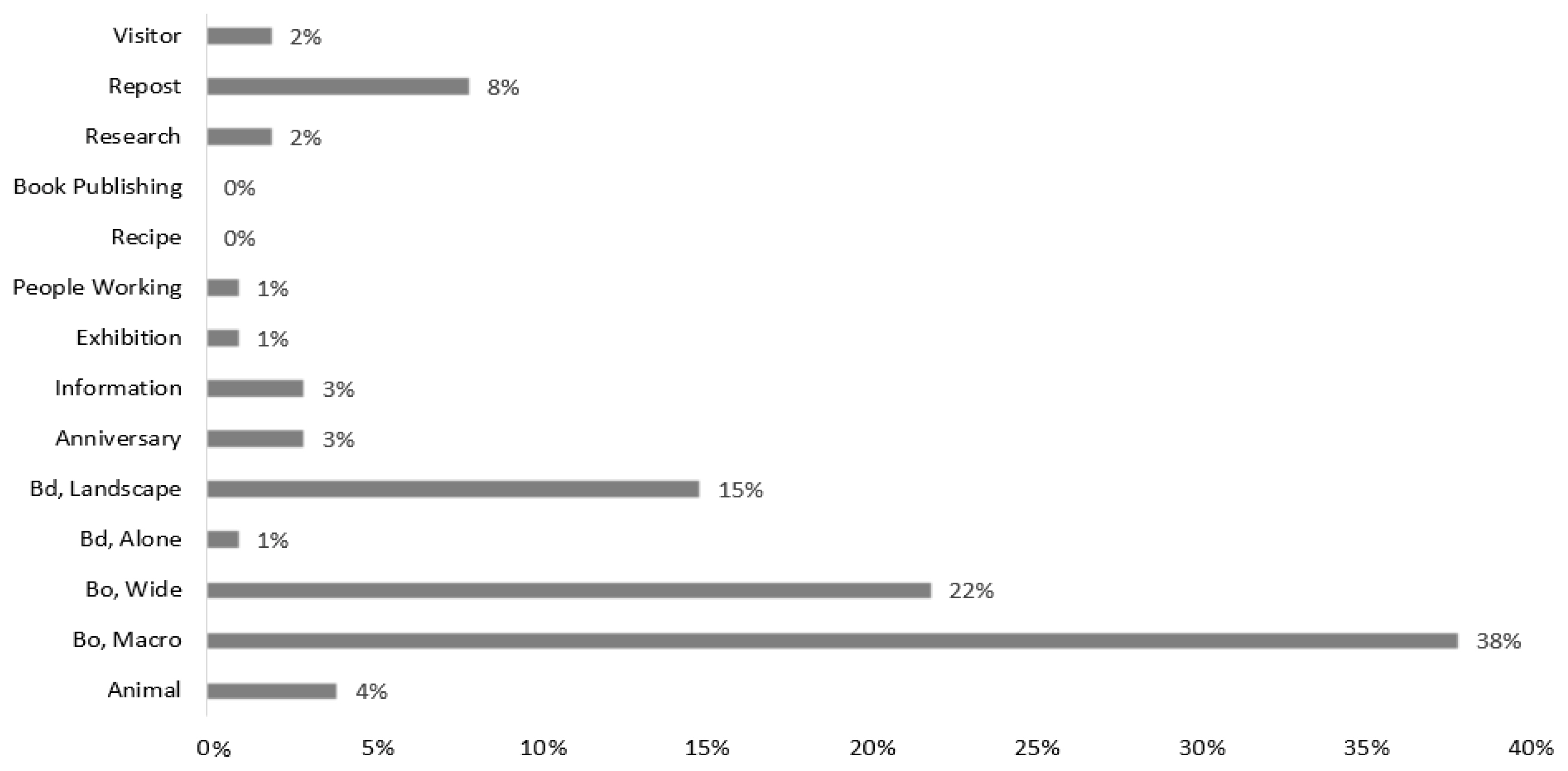

Through analyzing the posting status of 14 content types for a total of 850 pieces of content from November 6, 2014 to July 3, 2020, close-ups of plants were exposed at the highest rate, at 38%, followed by plant colonies (22%), site-specific landscapes (15%), and reposts (8%) (Fig. 2).

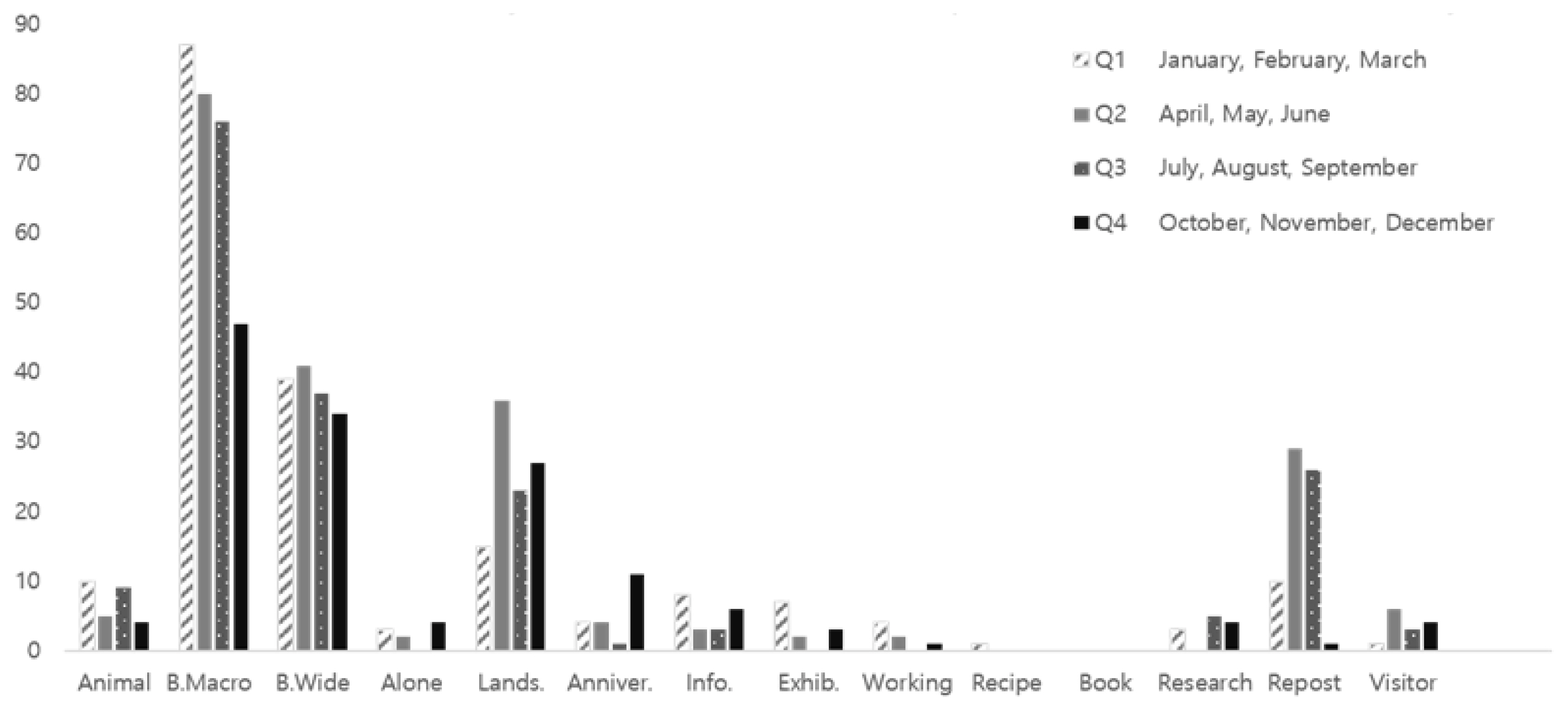

It was analyzed that, by place-based content type in the first to fourth quarters in Kew Gardens, plant colonies were steadily exposed in all four seasons, while plant close-ups were intensively exposed in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd quarters; place-specific landscapes in the 2nd and 4th quarters, and reposts in the 2nd and 3rd quarters (Fig. 3).

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to analyze the correlation between the 14 place-based content types derived from Kew GardensŌĆÖ Instagram account and the structure of the two user reactions, ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ (Table 5). First of all, through preliminary analysis, it was confirmed that there were no problems with normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity.

By verifying the correlation with ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ among the structure of user reactions for the 14 types of place-based contents in the botanical garden at a significance level of 0.001, the regression model was found to be statistically significant (F = 78.690, p < .001), and the explanatory power of the model was about 58.6% (adjusted R2 was 57.8%) (R2= .586, adj R2=.578). On the other hand, the Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.074, which was an approximation of 2, so it was evaluated that there was no problem in the assumption of the independence of the residuals; and the variance inflation factors (VIFs) were also 1.008 to 1.230, which was less than 10, indicating that there was no multicollinearity problem.

By testing the significance of the regression coefficient, the following were found to have a significant effect on ŌĆ£Likes,ŌĆØ in order of significance: plant close-ups (╬▓ = .523, p < .001), plant colony (╬▓ = .308, p < .001), place-specific landscape (╬▓ = .266, p < .001), information (╬▓ = .183, p < .001), anniversary (╬▓ = .151, p < .05), research (╬▓ = .143, p < .001), animal (╬▓ = .131, p < .001), exhibition (╬▓ =. 122, p < . 001), visitor (╬▓ = .114, p < .001), people working (╬▓ = .110, p < . 001).

Next, the results of verifying the effects of 14 content types on ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ showed that the regression model was statistically significant (F = 25.023, p < .001), and the explanatory power of the model was about 31.0% (adjusted R2 was 29.8%)(R2= .310, adj R2= .298). Meanwhile, the Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.933, which was approximately 2, so it was evaluated that there was no problem in the assumption of the independence of the residuals; and the VIFs were also 1.008 to 1.230, which were all less than 10, indicating that there was no multicollinearity problem.

By testing the significance of the regression coefficient, the following were found to have a significant effect on ŌĆ£Comments,ŌĆØ ranked in order of significance: plant close-ups (╬▓ = .292, p < .001), anniversary (╬▓ = .258, p < . 001), place-specific landscape (╬▓ = .221, p <.001), plant colony (╬▓ = .204, p < .001), information (╬▓ = .161, p < . 001), people working (╬▓ = .113, p < . 001), visitors (╬▓ = .106, p < . 001), exhibitions (╬▓ = .100, p < . 001).

To summarize the analysis results, first, it can be considered that the Kew Gardens Instagram account content that users prefer includes knowledge about plants, which is consistent with the botanical gardenŌĆÖs role as a public institution. This involves the finding that plant close-ups and plant colonies are the contents that have the greatest impact on both ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ when comparing the size of the standardized coefficients of multiple regression analysis. Since the contents containing plant close-ups and plant colonies are composed of vivid images and videos along with specific and specialized knowledge about plants such as the scientific name, form, and flowering period of the plant, such results can be considered to show the reactions of usersŌĆÖ expectations to the specific space itself, called a ŌĆ£botanical garden.ŌĆØ

Second, the type of place-specific landscape, which represented the second largest portion of user reactions after plant-related contents, can be regarded as contents containing the characteristics of a place representing Kew Gardens, which consists of the facilities of Kew Gardens and the surrounding landscape, including Palm House, Kew Palace, Princess of Wales Conservatory, Temperate House, Great Pagoda, and Kew Hive. This indicates that in addition to the knowledge of plants that can be expected from a botanical garden, users actively respond to contents sharing places and landscapes where knowledge related to history and culture harmonizes with nature; and it confirms that this is an important factor to consider when botanical gardens and national parks produce content in the future to induce usersŌĆÖ interest.

Third, it is considered that the anniversary-related content concentrated in the fourth quarter was used to increase the intention to visit the place and form a positive placeness through online word-of-mouth communication by sharing posts related to anniversaries such as Christmas and Halloween and utilizing the spatial characteristics as a medium. The following content can be interpreted as having a significant effect on both ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ as life-oriented content that enables interaction through usersŌĆÖ participation: content related to social and cultural communication familiar to users with high sympathy, such as anniversaries including ValentineŌĆÖs Day, Easter, and Christmas; and in the same context, information-type content containing various useful information on exhibitions of works such as paintings or photographs of plants, events in the botanical garden, or discounts on tickets.

Fourth, animal and research content types had a significant effect on ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ while showing low significance with ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ Considering that ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ are more active behavioral reactions than ŌĆ£Likes,ŌĆØ it can be observed that the level of empathy and behavioral variables are markedly different depending on the type of content. This confirms an efficient method for providing information by type and utilizing images when a specific public institution such as a botanical garden tries to share and spread its content in the future.

User interactions with the image contents of Kew Gardens were found to be shown as independent behavioral reactions for each content type. It can be interpreted that users show the behavioral reaction of ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ which is an easy way to express empathy, for content perceived as useful information, and that they respond with ŌĆ£Comments,ŌĆØ a more direct form of communication, only to content that provides expert knowledge or arouses sufficient empathy. To induce usersŌĆÖ recommendations and word of mouth through image-based social media, it will be necessary to produce and provide content in consideration of the characteristics of social media and user behavior. In particular, since social media contributes to overcoming informational limits in relation to the attributes of experiential products that can be known only after using the products and services (Gruen et al., 2003), it can be seen that it plays an important role in forming a positive image and attachment to a place through the userŌĆÖs place awareness by providing various information about a place and sharing a space online.

The purpose of this study was to determine the characteristics of contents and user reactions by analyzing the Instagram content type of Kew Gardens, a representative public botanical garden in the UK. Spatial information and experiences produced and shared in non-physical spaces such as social media influence the formation of placeness for those who experience a place indirectly through user reactions such as ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ or ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ and the place where a positive image is built induces active recommendations and word-of-mouth from social media users. Although various local governments and public institutions are also actively utilizing social media as a tool for publicity and communication, studies analyzing the types of content and user reactions in specific public places such as botanical gardens have been quite limited.

Therefore, in this study, we divided the content of the Kew Gardens Instagram account into 14 types and analyzed the effect of those types on the number of ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Comments,ŌĆØ which are the structure of user reactions. Plant-related contents containing plant close-ups or plant colonies, contents containing place-specific landscapes in the botanical garden, and content related to anniversaries showed a more significant effect on both the number of ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ than other content types. This suggests the following implications.

First, the social media content of the botanical garden induced an active reaction from users with plant photo contents such as plant close-ups and plant colonies that fit the original purpose of the specific space called a botanical garden; second, the account induced usersŌĆÖ reactions with content that combines professional information on plants and humanistic knowledge about historic buildings in the botanical garden; and third, it is considered that content tailored to the tastes of the general public, containing life-oriented information, induced usersŌĆÖ reaction.

This study was conducted to understand the type and influence of place-based content posted on social media through a case study of place marketing in an overseas botanical garden; for the purpose of establishing effective social media utilization strategies for public institutions such as botanical gardens, arboretums, and national and public parks, we collected and analyzed the contents of a botanical garden on Instagram, an image-based social media. However, this approach has the following limitations.

First, when determining the category for analysis to refine data, there were not enough previous studies that could be referenced in relation to botanical gardens and arboretums, so three representative botanical garden accounts and classification of general place types were referenced. Second, comments were analyzed based on the total number of comments, and negative comments were not filtered. It seems necessary to analyze comments by extracting associated words and separating positive and negative words. Third, considering that the user reactions of ŌĆ£LikesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£CommentsŌĆØ are used differently as independent behavioral variables rather than interactively, in the future, the scope of data collection should be expanded to analyze and supplement specific types of public space content in detail.

Fig.┬Ā3

Monthly distributions of post typology (November 2014 to July 2020). B.Macro: botanic, macro, B.Wide : botanic wide, Alone: building alone, Lands: building, landscape, Anniver: anniversary, Info: information, Exhib : exhibiton, Working : people working.

Table┬Ā1

Kew GardensŌĆÖ Instagram Account status

| Account | Posts | Followers | Following |

|---|---|---|---|

| @kewgardens | 898 | 41.3k | 203 |

Table┬Ā2

Post typology for botanic gardens

| Codes by Sevin (2013) | Codes for botanic gardens | Codes by Sevin (2013) | Codes for botanic gardens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Animal | Events | Anniversary |

| Botanic, macro | Information | ||

| Botanic, wide | Exhibition | ||

|

|

|||

| Characteristics | Building, alone | People working | |

|

|

|||

| Building, landscape | Parks | Research | |

|

|

|||

| Business | Recipe | Twitter related | Repost |

|

|

|||

| Book publishing | People | Visitor | |

Table┬Ā3

Explanation for coding

Table┬Ā4

Inter-coder reliability

Table┬Ā5

Regression analysis (N = 850) of dependent variables (likes and comments) and the 14 independent variables N = 850

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Dependent Variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Likes | Comments | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| B | S.E | ╬▓ | t | p | R | B | S.E | ╬▓ | t | p | R | |

| Animal | 4162.059 | 708.325 | .131 | 5.876*** | <.001 | 7 | 23.559 | 12.382 | .055 | 1.903 | .057 | |

| Botanic, Macro | 5386.543 | 229.456 | .523 | 23.475*** | <.001 | 1 | 40.713 | 4.011 | .292 | 10.151*** | <.001 | 1 |

| Botanic, Wide | 4181.441 | 302.842 | .308 | 13.807*** | <.001 | 2 | 37.543 | 5.294 | .204 | 7.092*** | <.001 | 4 |

| Building, Alone | 2594.000 | 1376.737 | .042 | 1.884 | .060 | 21.889 | 24.065 | .026 | 0.910 | .363 | ||

| Building, Landscape | 4427.952 | 370.904 | .266 | 11.938*** | <.001 | 3 | 49.935 | 6.483 | .221 | 7.702*** | <.001 | 3 |

| Anniversary | 5698.042 | 843.076 | .151 | 6.759*** | <.001 | 5 | 132.375 | 14.737 | .258 | 8.982*** | <.001 | 2 |

| Information | 7400.952 | 901.286 | .183 | 8.212*** | <.001 | 4 | 88.000 | 15.755 | .161 | 5.586*** | <.001 | 5 |

| Exhibition | 6507.833 | 1192.289 | .122 | 5.458*** | <.001 | 8 | 72.167 | 20.841 | .100 | 3.463*** | <.001 | 8 |

| People Working | 5888.500 | 1192.289 | .110 | 4.939*** | <.001 | 10 | 82.167 | 20.841 | .113 | 3.942*** | <.001 | 6 |

| Recipe | 173.000 | 4130.211 | .001 | 0.042 | .967 | 9.000 | 72.196 | .004 | 0.125 | .901 | ||

| Book Publishing | 462.000 | 2920.500 | .004 | 0.158 | .874 | 10.000 | 51.051 | .006 | 0.196 | .845 | ||

| Research | 7091.500 | 1103.845 | .143 | 6.424*** | <.001 | 6 | 32.214 | 19.295 | .048 | 1.670 | .095 | |

| Repost | 544.470 | 508.394 | .024 | 1.071 | .284 | 7.515 | 8.887 | .024 | 0.846 | .398 | ||

| Visitor | 5118.000 | 1001.723 | .114 | 5.109*** | <.001 | 9 | 64.471 | 17.510 | .106 | 3.682*** | <.001 | 7 |

|

|

||||||||||||

| F = 78.690 (p < .001), R2 = .586, D - W = 1.074 | F = 25.023 (p < .001), R2 = .310, D - W = 1 .933 | |||||||||||

References

Ariel, Y, R Avidar. 2015. Information, interactivity, and social media. Atl J Commun. 23(1):19-30.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2015.972404

Baik, SH 2004. The introduction of art festivals in small cities and the creation of placeness. J Korean Geogr Soc. 39(6):888-906.

Cho, KE, JA Park. 2008. Mass mediaŌĆÖs reporting tendency toward leisure and tourism. J Tour Sci. 32(4):389-410.

DMC Media2020 2020 Social media usage behavior and ad contact attitude analysis report. DMC Report Premium 1-338. Retrieved from https://www.dmcreport.co.kr/report/surveyReport/premiumView?reportcode=DMCSRP20200046&drtopdeth=RPT_TYPE_3&keyword_type=R_EPORT_KEYWORD_1

.

FKII2006 IT Issue Report - What is social media? FKII Digital 365 6:54-55. Retrieved from http://pds7.egloos.com/pds/200804/01/89/what_is_social_media.pdf

.

Gruen, TW, T Osmonbekov, AJ Czaplewski. 2006. eWOM: The impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. J Bus Res. 59(4):449-456.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.10.004

Holsti, OR 1969. Content analysis for the social science and humanities MA, U.S.A: Addision-Wesley.

Hong, SH 2012. A study on experiential characters of the place : for the places with the well-built ŌĆśSense of placeŌĆÖ in Seoul. MasterŌĆÖs thesis. Seoul National University, Seoul. Korea.

Guerrero, P, MS Moller, AS Olafsson, B Snize. 2016. Revealing cultural ecosystem services through instagram images: the potential of social media volunteered geographic information for urban green infrastructure planning and governance. Urban Plan. 1(2):1-17.

https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v1i2.609

Kim, CW, JH Choi, YH Moon. 2012. The impact of brand SNS commitment on brand loyalty. Korean Acad Commodity Sci Technol. 30(2):107-116.

https://doi.org/10.36345/kacst.2012.30.2.011

Kim, HB 2016. Effects of Instagram User Personality on Brand Satisfaction and Loyalty. J Korea Contents Assoc. 16(6):450-461.

https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2016.16.06.450

Kim, JE, C Park, AY Kim, HG Kim. 2019. Analysis of behavioral characteristics by park types displayed in 3rd generation SNS. J Korean Inst Landsc Archit. 47(2):49-58.

https://doi.org/10.9715/KILA.2019.47.2.049

Kim, JH 2015. A Study on interactions between archives and users by using social media-based on the cases of national archives of the U. S and the UK - J Korean Libr Inf Sci Soc. 46(3):225-253.

Kim, SK 2003. ICT use for place marketing of local governments. J Korean Assoc Reg Inform Soc. 6(1):21-46.

Lee, EJ, GT Choi, BA Rhee. 2019. A study on museum instagram hashtag analysis from the convergent perspective: case studies of Muse du Louvre and Centre Pompidou. Korean Soc Sci Art. 37(1):211-222.

https://doi.org/10.17548/ksaf.2019.01.30.211

Lee, HN 2019. Place-image marketing strategies via social media on urban public spaces. J Brand Des Assoc Korea. 17(2):179-190.

https://doi.org/10.18852/bdak.2019.17.2.179

Lee, JH, HS Han, SH Jwa. 2007. A study on the methodology of developing city brand identity : cases of cities in Gyeonggi Province. Gyeonggi Res Inst. 11:3-6.

Lee, KM, CD Kim, SE Kim. 2010. Branding Seoul strategy. Policy study report The Seoul Institute. 23:1-187.

Nam, MJ, EJ Lee, JH Shin. 2015. A method for user sentiment classification using Instagram hashtags. J Korea Multime Soc. 18(11):1391-1399.

https://doi.org/10.9717/kmms.2015.18.11.1391

Park, SH, DR Jang. 2009. Rebirth of Place Seoul, Korea: Design House. (pp. 366 p.

Park, SY, W Oh. 2019. A trend analysis of floral products and services using big data of social networking services. J People Plants Environ. 22(5):455-467.

https://doi.org/10.11628/ksppe.2019.22.5.455

Seo, DJ, JH Lim. 2016. A study about public space pattern for place identity. Korean Inst Spat Des. l1(1):89-99.

Seo, JY, HB Kim, HK Ha. 2020. A study on the spatial information and experience the place in online - the case of online information transmission and acceptance of the Seoul Botanical Park. J Korea Lands Counc. 12(1):29-42.

https://doi.org/10.36466/KLC.12.1.3

Sevin, E 2013. Place going viral: Twitter usage patterns in destination marketing and place branding. J Place Manage Dev. 6(3):227-239.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-10-2012-0037

Shin, HT, SJ Kim, JW Sung. 2020. Key words analysis of arboretum and botanical garden using big data. J Korean Inst For Recreat. 24(2):1-10.

- TOOLS