Cultural Symbolism and Acculturation of Temple Plants in China: Focused on ‘Bodhi Tree’

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Plants in temples are the results of cultural symbolization that embraces the experience and enlightenment of humans about life. As a way to improve the acceptance of the foreign religion, China gave cultural symbolization to plants in temple gardens through integration with traditional cultures and the understanding of the nature of plants themselves. This study aimed to identify cultural symbolism and signs of acculturation associated with Buddhist plants, targeting Bolisu, the most essential and symbolic plant in temple garden forests in China and Korea.

Methods

The morphological and ecological characteristics of plants, functions, the texts that contained the history of Buddhism and literary works were examined through literature review, and the relation of Ficus religiosa with its planting conditions and nature, and Buddhist culture was explored. In addition, the cultural value of Buddhist plants themselves in establishing temples and the reason why Bolisu was planted in temples were reviewed through time series analysis. The obtained results were interpreted using an inductive method to identify substitutes for F. religiosa, cultural symbolism and signs of acculturation.

Results

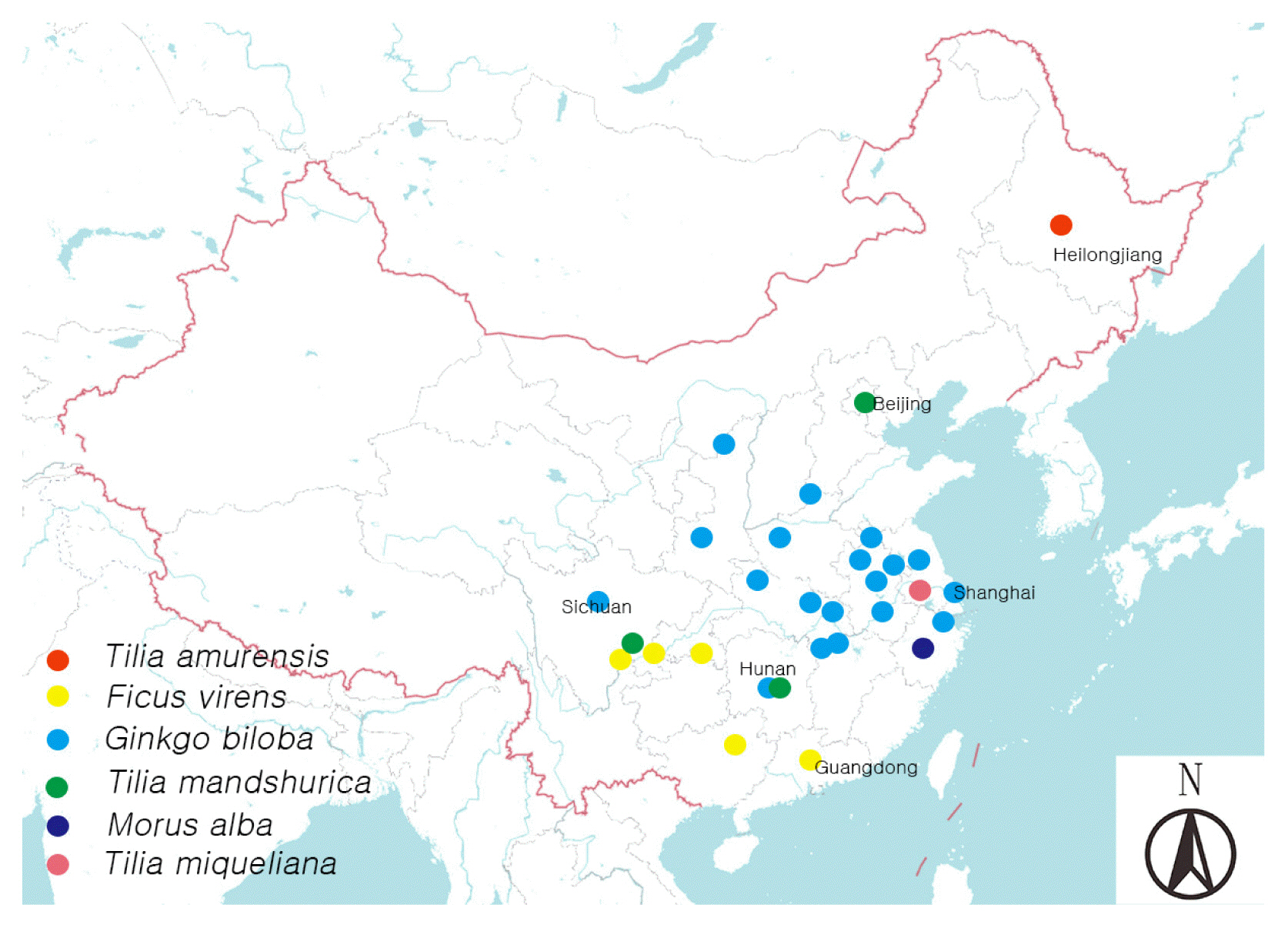

F. religiosa as one of the three holy trees and the five trees and six flowers in Buddhism is known as the original Bolisu. Since it grows well and is widely distributed in regions that accepted Indian Buddhism, it became the most representative holy tree in Buddhism. From the perspective of tree shape and nature, F. religiosa is in line with the Buddhist spirit of saving those in need with mercy and redeeming mankind, and figuratively shows that perfection can be attained like the fruit of Bolisu. Chines Buddhism had adopted highly symbolic plants for a long period of time as a means to spread the same belief and doctrines as Indian Buddhism. In China, however, there were only limited areas suitable for the growth of F. religiosa, and for this reason, borrowed Bolisu trees including Tilia. miqueliana, T. mandshurica and T. amurensis and other plants such as F. virens Ait. var. sublanceolata, G. biloba and M. alba were planted as a substitute in most regions, having been given with symbolism and belief as Bolisu.

Conclusion

Chinese Buddhism planted the same plants as Indian Buddhism in order to enhance symbolism and also similar substitutes to express the same symbolism. This is a kind of acculturation and its influence and customs were not limited to China, but were introduced to Korea, The difference between China and Korea was that G. biloba was excluded from the substitute for Bolisu in Korea.

Introduction

China’s cultural landscape heritage is one of the areas prioritized by the government in policies along with religion-related projects, and in line with that the Chinese government has actively implemented projects to protect and restore temple garden forests (Huo, 2020). In particular, plants as a key component of garden landscapes in Buddhism, play a role of improving scenic beauty as well as representing Buddhist doctrines and symbols within temple garden forests as a meaningful landscape. Many studies have been conducted on temple garden forests, but there were only few studies on the symbolism of plants related to Buddhism. It is because studies on plant cultures mostly researched them in the context of historic events, customs and various humanistic elements in a broad sense, and thus it is believed to be difficult to set the scope of studies and objectively infer. Meanwhile, Huang (2010) analyzed the culture of plants in early China connoted in Shijing on taxation and labor, marriage and love, farming, etc.

The influence of religious ideologies on China’s traditional plant culture is a research area of great importance. It is because plants had to meet two functions and meanings - environmental beautification and intensified Yijing - in the process of creating temple garden forests. In Buddhism, in particular, as one of the major religions in the world, some plants were recognized as a universal symbol of the religion in countries like Korea that introduced Buddhism.

Against this backdrop, this study conducted a literature review on Bolisu tree known as the most essential and symbolic plant in temple garden forests in Korea and China to explore the way of expressing Buddhist plants that were used as a substitute for Bolisu and thus to trace the symbolism and meaning of Bolisu connoted in the culture of Buddhism plants and signs in acculturation.

Research Methods

Subjects and scope

In this study, Bolisu and related species among Buddhist plants shown in the development of Buddhist culture in China were targeted as key subjects. Since Buddhism in China was introduced from India, the culture of Buddhist plants in China was compared with that in India. Many Buddhist plants are closely related to the culture and regional flora of the place where temples were built. In addition, the development history of Buddhism in China was reviewed to examine the influence of rulers in Chinese ancient society on Buddhist plants and compare with temples in Korea. In general, the types of plants written in the Buddhist scriptures can be divided into holy trees, heaven flowers1), medicinal and aromatic plants, edible plants, plants used as a material or a raw material, and religious plants (Park, 2012). The scope and subjects of this study were limited to holy trees.

Terminology

The key terms used in this study were defined for the purpose of operation as follows.

Temple plant

A temple plant is closely related to the beginning and development of Buddhism and thus is perceived to have a special meaning. Buddhist plants in this study were divided into broad and narrow-sense types. The plants of broad-sense types were defined as a group of plants that were planted in temples for a special meaning due to their association with the development of Buddhism, while those of narrow-sense types are associated with the beginning and development of Buddhism and thus mostly mean Buddhist plants in India.

Bodhi tree

Ficus religiosa is native to India and also is called as an enlightenment tree as Buddha attained enlightenment under the tree. There are also many Tilia species used as a substitute for F. religiosa including Bodhi trees, Tilia mandshurica and T. amurensis and they are generally called as Bolisu trees. In this study, F. religiosa from India is defined as original Bolisu, and the rest substitutes are defined as borrowed Bolisu. Both are combined and called as Bolisu.

Cultural symbolism

Culture is a material and moral asset achieved in the history of humans. Edward Burnett Tylor, an English anthropologist, mentioned in his book, Primitive Culture (1871), “culture is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society (Edward, 1871)” and first started to use culture as a technical term.

That is, humans created material and moral cultures necessary for their survival using plants and compared their seven emotions to plants from the perspective of social development, placing special ideas and emotions on plants (Lin, 2009). The metaphors and symbolic meanings of plants were defined as cultural symbolism in this study.

Acculturation

Acculturation is a phenomenon in which, as more than two heterogeneous cultures were directly encountered, either or both sides bring about a change in the shape of an original culture, and in this study the phenomenon in which the original Bolisu (F. religiosa) was replaced by a borrowed Bolisu.

Data collection and literature review

This study was conducted as a phenomenological study focusing on literature review. In particular, morphological and ecological characteristics, basic functions, the texts that contained the history of Buddhism, and literary and artistic works were reviewed to examine the meaning and value of Buddhist plants. In addition, the use cases of plants in traditional temples in China were surveyed and analyzed to obtain inductive results. In the process of discussing Buddhist plants, the expressions related to Buddhist cultures were quoted. Mostly, ancient literary works were searched to explain the connotative meaning of plants in China’s traditional cultures.

Analysis and interpretation

Buddhist plants were divided into Indian and Chinese Buddhist plants, and the utilization of plants was divided into regional and cultural values. In addition, morphological and ecological characteristics, the text that contained the history of Buddhism and literary works were reviewed. The culture of Buddhist plants is the product of the convergence of traditional culture and Buddhist doctrines, and affects the ecological and aesthetic views of Buddhism and the species of plants planted in temple garden forests. The diversity of factors results in the profound connotation of the culture of Buddhist plants and expresses diversity as well. From this perspective, the plant culture of Buddhism was identified through the landscape of plants in the major temples that exist today, and was explained using the literary works associated with Buddhism as a medium.

As such, cultural symbolism was analyzed using an inductive method based on the results of the literature review, focusing on F. religiosa. In particular, the cultural value of Buddhist plants themselves when temples were established and the reason why Bolisu was planted in the temples were discussed through time series analysis. In addition, substitutes for F. religiosa and cultural symbolism were interpreted.

Results and Discussion

Introduction of Chinese Temple Plants and Cultural Symbols

History of the development of Buddhism in China

(1) The development period of the Yanghan Northern and Southern Dynasties

Buddhism was first introduced to China during the Yanghan Dynasty with the history of 1,900 yeas. According to the level of development, the period can be explained with three characteristics as follows. The period from the late Eastern Han Dynasty to the Northern and Southern Dynasties was the time in which Buddhism started to be spread and expanded and can be explained with the three characteristics.

(2) The prosperous period of the Sui and Tang Dynasty

Buddhism in China in the 4th and 5th centuries established a relatively systematic academic foundation. During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the northern and southern regions of China started to be politically unified after a series of long-lasting wars, and the economy back then also entered the period of prosperity. Under the environment, Buddhism also started to flourish. During the prosperous period of Buddhism, the following phenomena were observed.

First, Buddhism was spread with the belief of previous life and reincarnation coupled with the beliefs in spiritual beings in ancient society back then, which led to the atmosphere of protecting rulers and the approval of rulers. The main reason why rulers valued especially Buddhism and used it politically was that the rulers themselves revered the doctrines of Buddhism and that Buddhism was a political tool fitting both social situations and the needs of the time such as edifying the public.

Second, different religious orders were formed and Buddhist scriptures were translated. Back then, the Northern and Southern politics entered the period of unification, but differences in the Buddhist doctrines between the two regions, far from being reduced, resulted in a new phase, forming new Buddhist studies. As a result, Buddhist schools in the Sui and Tang Dynasties entered the period of diversity. This indicates that Buddhism back then was developed and transformed into a new Buddhist culture based on traditional Buddhism by being converged with China’s traditional culture. Zen (禅宗) and Pure Land Buddhism (净土宗), the mainstream Buddhist schools in China, also showed that the foundation of new schools met the political landscape of China back then and also the development of cultures by converging Buddhism with other ideas such as Confucianism and Taoism.

Lastly, it must be pointed out that Buddhism was converged with China’s traditional culture. The reason why Buddhism had spread and had not been extinct in China for centuries is that the religion was well converged with the culture of the time and also survived in the early period with the ideological base of Xuanxue (a philosophy of Taoism) and Taoism. Buddhism started to gradually form its own culture from the Sui and Tang Dynasties and entered the period of prosperity (Gao and Zhang, 2015). Buddhism also converged ethical ideas from Taoism and Confucianism in the society of the time in the continuous process of Sinification to induce the establishment of the foundation of state affairs fitting Chinese society and continuous popularization, maximizing the number of believers.

(3) The Maturity period of the Song Dynasty

Many temples were damaged by wars from the five dynasties in the late Tang Dynasty to the early Song Dynasty and thus many monks had to return to secular life. In particular, many rulers in the Song Dynasty tended to have a protective attitude towards Buddhism, but Buddhism back then did not affect the prosperity of Buddhism in the Sui and Tang Dynasties. That is, many Buddhist schools in the Song Dynasty also started to converge and learn from each other to become one and their synergistic effects made Zen and Pure Land Buddhism the two largest schools of Buddhism in China.

Value and cultural symbol of temple plants

(1) Value of temple plants

The culture of Buddhist plants is an important link between Buddhist culture and China’s traditional culture. In the process of accelerating the localization of Buddhism, aesthetic ideas as well as Buddhist culture were expressed in different forms, which can significantly contribute to research on historical issues related to Buddhism. In other words, temple plants have historic value above all, and the plant culture of Buddhism, as one of the major genres of many forms of arts of Buddhist temple forests, contributes to the greenification of temple environments and the creation of Yijing, and is associated with many cultural genres and thus various areas including sculpture, painting and literature. Temple plants are deeply related to the understanding of artistic value. In addition, the culture of Buddhist plants, as an important part of China’s traditional plant culture, tends to compare Buddhist doctrines with plants. For example, T. miqueliana means wisdom and Nelimbo nucifera means the four virtues of Nirvana (常⋅乐⋅我⋅净) (Shi and Shen, 2012). Buddhism cherished inner meanings as introducing the idea, ‘matter itself is voidness, voidness itself is matter’ and the cultural value that temple plants have must not be overlooked. The culture of Buddhist plants as an important component of landscape greenery in Buddhism addressed the unification of species in the plant landscape of temples and the problem of departing from history in China and can create small-size gardens with Buddhist atmosphere. Temple garden forests have to meet the ideological direction of locations and Buddhist plants also have significant cultural implications in reproducing the characteristics of Buddhist holy lands in temple garden landscapes in the process of restoring Buddhist landscape garden forests.

(2) Cultural symbol

The life of monks is closely related to plants in the history of Buddhism. The symbol of various plants and the viewpoint of Buddhism towards Buddhist plants composed the content of national culture and the cultural symbol of Buddhist plants is expressed not through daydreams but through symbolism. As such, the cultural symbol of temple plants is the message that contain humans’ visual, hearing, gustatory and olfactory feelings and cultural ideas. Therefore, the process of identifying the cultural symbolism of Buddhist plants includes mutual transformation based on the nature of plants and China’s traditional culture (Ju and Zhai, 2001).

The symbolic plants that are associated with Buddhism and are observed mostly in temples in Korea include Nelumbo nucifera, Viburnum sargentii for. sterile, Hydrangea macrophylla, F. religiosa, Tilia megaphylla, Magnolia kobus and Musa basjoo. T. mandshurica or Tilia. miqueliana of which fruit looks like Buddhist prayer beads are used as a substitute for Bolisu. Meanwhile, Salix spp. was not planted in many temple garden forests in China, but it is a unique cultural symbol. Salix spp. is called as ‘liǔshù (柳樹)’ and ‘liǔ (柳)’ pronounced the same as ‘liǔ (留, meaning leave),’ which makes Salix spp. planted in China for the purpose of praying for friends or God’s blessing (Yuan, 2013). In addition, Morus alba is called as ‘Sāngshù (桑树)’ in China, and ‘Sāng (桑)’ pronounced the same as ‘Sāng (丧, meaning funeral).’ For this reason, it is not planted in temple garden forests or gardens in private houses. That is, there is an old saying in China that M. alba must not be planted in private houses or temples (Nan, 1996), and the reason is that both the characters, ‘桑’ and ‘丧’, pronounced the same. In addition, there has been a basic principle for planting, “Do not plant M. alba in front of houses, Salix spp. in the back side and Populus spp. in front of doors2).” However, the political background of each time significantly affected the appearance of Buddhist plants, and one notable case is M. alba planted in Baengma Temple, the first temple in China, located outside the Gate of Western Harmony (西雍門) in Luoyang, China3) (Fig. 1). The tree located in the eastern side of the Mahavira Hall is known as the fourth generation M. alba grown from the dead stump though its original age is unknown. The current size of the tree is as follows: girth 5 m and height 13 m, and the body leaned to the south with branches and leaves grown thickly. The crown projected area of the tree is 400 m2.

The tree was planted upon the command of a powerful man, but M. alba has been called as ‘jixiangsang (auspicious mulberry).’ M. alba with an ominous meaning was planted taking advantage of the political ideology of the time, but from a positive perspective, it is notable that it turned around as jixiangsang.

The cultural symbol of the Bodhi tree

Geographic planting environment

About 500,000 species of plants live on earth, and their distribution is affected by environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity. Ancient India, the origin of Buddhism is in a tropical monsoon climate. Although the climate is sweltering, the species of trees in the mainland are mostly tropical and subtropical plants. In particular, F. religiosa or Shorea robusta grow wild broadly in Hindustan. Meanwhile, China has a large territory, showing significant differences in temperature between north and south. As shown in Fig. 1, however, the distance between Guandong and Gungxi Province is close, and thus a variety of tropical tree species can grow (Gao and Zhang, 2015).

Although most of the plants related to Buddhism that grow wild in the mainland India cannot be easily planted and grow in most regions in China (Fig. 2), the framework of cultural symbolism was established in China through traditional plants taking advantage of the diversity of plants in China. As a result, plants for temples were selected based on the functionality of spaces in temples and climatic characteristics in their location converged with the plant culture and aesthetic preference of the mainland.

Growing area of Ficus religiosa in China. Reprinted from Plant Photo Bank of China. Retrieved from http://ppbc.iplant.cn

The species epithet of F. religiosa shown in Fig. 3 in India, religiosa, means ‘religious.’ As Buddha attained enlightenment under the tree after 6 years of meditation and thus became the symbol of Buddhist culture as a holy tree. As defined earlier, the tree is original Bolisu, and is called as Bo tree in the East India, as Pippal tree in Ceylon and Malaysia and as Po tree in Thailand. As F. religiosa as an evergreen broad-leaved tall tree of the Moraceae family is sensitive to cold, it is difficult to grow it outdoor in China, but it appeared in the Zen Poems (禅诗) in the Sixth Patriarch of Huineng (六祖慧能).

Boli is not a tree, and a bright mirror is not a stand. As there is nothing from the first, where does the dust come from?

The poem expands the implication of planting Bolisu and indicates that it is not necessary to insist on planting F. religiosa only but that it can be substituted by other plants according to the flora of the mainland China. Since the growth environment of F. religiosa is complicated, it was planted only in tropical subtropical regions in China. In regions where F. religiosa cannot grow well, F. virens Ait. var. sublanceolata in the same genus (Ficus) of F. religiosa, or Celtis bungeana in the genus of Celtis or Syringa reticulata in the genus of Syringa were planted as a substitute for Bolisu.

The Three Holy Trees of Buddhism Five Trees and Six Flowers

Along with the plants related to the life of Buddha in the Buddhist scriptures, plants appear in various ways such as representing the doctrines of Buddhism and using in comparison and symbolization (Min, 2015). Among them, Saraca indica that appeared in Lumbini about the birth of Buddha was viewed as the ‘birth tree’ and F. religiosa as the ‘enlightenment tree.’ Along with S. robusta as the ‘Nirvana tree,’ they are called as the three holy trees (Table 1).4)

Temples have the three holy trees as well as the five trees and six flowers as shown in Table 2. F. religiosa is at the center of them, and is recognized as an important symbolic Buddhist plant as a holy tree under which Buddha attained enlightenment. It had to be planted in every temple, but mostly substitutes were planted due to its complex growth conditions.

Alternative planting of Bodhi tree Symbolic implications of Bodhi

‘Boli’ means in Sanskrit in China determination, wisdom, knowledge and road and in a broad sense symbolizes the meaning of blocking all the worries in the world and giving great wisdom. In other words, when Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bolisu tree, the symbol was ‘Boli,’ that is, ‘determination’ and thus ‘Bodhi seeds’ connoted ‘achieving Inner Buddha.’

The Buddhist scriptures state that infinite charity can be achieved by chanting a Buddhist prayer with Buddhist prayer beads made of Bodhi seeds. In Buddhist Dictionary written by Ding (2011), Buddhist prayer beads can be made of Bodhi seeds (Bodi—ci in Tibetan). Until now, however, Bodhi seeds was used as an accessory for general people not as an Buddhist item as Buddhism was developed in China. Since Bodhi seeds have a significant meaning to Buddhism, all the Buddhist prayer beads are called as Bodhi in China. In China, Bodhi seeds are not just the fruit of Bolisu, but a Buddhist item used in temples when chanting a Buddhist prayer, and only three types of Bodhi beads are frequently used in Buddhism in China.

Borija tree and Scrape tree

The shape of the leaves of T. amurensis is similar to that of F. religiosa and its fruit also looks like Bodhi seeds. For this reason, T. amurensis was planted as a substitute to Bolisu broadly in China as well as in Korea, and in some places it was called as Bolisu. For example, the species of trees planted in Guoqing Temple (国清寺) on Mount Tiantai in Zhejiang Province is T. amurensis, but they are naturally called as Bolisu. T. amurensis trees planted within Yinghuadian (英华殿) in Zijincheng in Beijing during the Ming and Qing dynasties also were conventionally called as Bolisu. The climate in the Southwestern region in China is dry and cold, which is not suitable to plant T. miqueliana, G. biloba, T. amurensis, etc. outdoor. Syringa reticulata var. amurensis, however, has tenacious vitality and strong adaptability and thus is broadly distributed in the Northern region in China. For this reason, it had been used as a source of food for a long time in the Northwestern region. The origin of Syringa reticulata var. amurensis is the temperate region in China, and was called as Seahae Bolisu in temple garden forests in Tibet where the annual precipitation and annual average temperature are low due to strong tolerance to cold and dryness. For this reason, it was also planted as a substitute instead of Bolisu (Gao and Zhang, 2015).

The fruit of Bolisu also commonly planted in temples in Korea as a holy tree is called ‘Borija’ in Korean and is used to make Buddhist prayer beads. The plant is generally known as Bolisu, but the scientific name is T. miqueliana. Most temples planted T. miqueliana with the seeds from China. When it was difficult to find T. miqueliana, T. mandshurica or T. amurensis were planted as a substitute and were recognized as Bolisu5).

The length of leaves of T. miqueliana compared to T. mandshurica is longer than the width of leaves, and its leaves have a long leafstalk, but only little hair (Lee, 2007). In addition, as shown in Fig. 4, the fruit of T. mandshurica is a globular shape, but that of T. miqueliana is more like an oval shape.

In addition, what is called as Bolisu tree in Korean is Elaeagnus umbellata, another deciduous broadleaf tree species in the family of Elaeagnaceae.

Acculturation of Bodhi trees

As such, F. religiosa is difficult to grow in a cold climate like the Northern region in China, and thus T. miqueliana, a similar Tilla tree, was planted as an substitute for Bolisu, a symbolic tree of Buddhism in China. The reason was that T. amurensis as a northern plan, can grow also in cold regions, and combined with the power of rulers back then people believed the word of rulers, “T. amurensis is that is to say Bolisu,” which also seemed to play a significant part. As shown in Fig. 5, T. amurensis was transplanted within Yinghuadian in Zijincheng, the palace of the Ming Dynasty. As a tree in emperors’ garden forest, they have been maintained very well until today. Qianlong Emperor in the Qing dynasty also wrote a poem about T. amurensis titled Yinghuadian Bolisu Poem. This also indicates that the ideology of rulers profoundly affected the plant culture of Buddhism.

Europe Tilia amurensis in Film exhibition in Forbidden City, Korea. Photographed by author on August 2020.

In cold regions like the Northeastern region in China, T. mandshurica was used as a substitute for F. religiosa. In particular, F. virens Ait. var. sublanceolata, mentioned earlier, is also a native plant in the Southwestern region in China and one of the species in the Ficus genus of the Moraceae family like F. religiosa. It has also a similar shape, and thus was used as a substitute for Bolisu in temples in Sichuan Province and Chongqing (Shi and Shen, 2012). Fig. 6 shows the Bolisu tree, that is T. miqueliana, opposite-planted within Geumsan Temple in Gimje, Jeonbuk, Korea.

In the culture of Buddhist plants in China, T. amurensis among substitutes for Bolisu was used as a substitute in China simply for its similar shape, but the one that was broadly planted and recognized as Bolisu in China is G. biloba. As the period of Buddhist culture was extended, more plants that had a symbolic meaning in Buddhism appeared accordingly. In Buddhism, G. biloba is called as ‘holy fruit’ and ‘holy tree’ and its holy and mystic color was used to expand the influence of Buddhism. There is even an old saying in China, “G. biloba must be planted in any temple.” Meanwhile, Buddha attained enlightenment under the tree of Pippala (प◌ीपल in Sanskrit) which was called as Bolisu and was widely planted in temples, being recognized as a Buddhist holy tree. As mentioned above, F. religiosa as a tropical or subtropical evergreen plant is difficult to grow in temperate and cold climates in northern regions, and for this reason, G. biloba was used as a substitute for Bolisu in many cases following the wisdom of high priests in China in an ancient time. Ecologically, as G. biloba is distributed broadly, adapts well, and has the outstanding shape and autumn colors of leaves, it was widely planted in temple garden forests. Since the physiological shape of G. biloba as well as its similar shape can be used to express humans’ wisdom, G. biloba at least in China showed the status similar to Bolisu and was commonly and widely planted (Fig. 8), which should be noted.

In addition, the softness and hardness of G. biloba and its wood grain are suitable for making Sahasrabhuja-aryaavalokiresvara (千手觀音) statues and Buddhists thought the statues made of G. biloba was lifelike. In particular, as the nails of the statues were slightly thin, G. biloba is also known as the ‘nail of Buddha.’ However, this symbolism was not embraced in Korea as it was.

There were other temple plants with symbolic significance than Bolisu. Although Buddhism in China is a foreign religion, it has its own symbolic plants based on the traditional culture of China as Buddhism in India did. Fig. 7 shows the summary of the acculuration phenomenon of Bolisu with those planted in temple garden forests as a substitute for F. religiosa in China including T. miqueliana, T. mandshurica, T. amurensis, F. virens Ait. var. sublanceolata, M. alba and G. biloba. The only difference in Korea was that G. biloba was excluded from substitutes for Bolisu.

Bodhi trees and culture-acculturated Borrowed Bolisu. Reprinted from Plant Photo Bank of China. Retrieved from http://ppbc.iplant.cn

As a foreign religion, Buddhism gradually assimilated into Chinese culture in the process of distribution, and this is a type of acculturation. The symbolism of Bolisu introduced from India used those in the family of Tilla or other trees as a substitute (Fig. 9), and as more than two heterogeneous cultures were directly encountered, the original shape of culture was substituted with other trees in China.

Conclusion

Plants planted in Buddhism have unique cultural symbolism embracing the experience and enlightenment of humans about life. Buddhism was a foreign religion in China, and thus cultural symbolism was given to Buddhist plants through the understanding of the nature of plants themselves and the combination of traditional culture in order for people to embrace the religion more easily. The method was used not only in China, but also in India, the origin of Buddhism, and the three holy trees and the five trees and six flowers were the example of cultural symbolism.

The planting environment and nature of F. religiosa was reviewed in line with Buddhist culture, and the original Bolisu, F. religiosa, was one of the three holy trees and the five trees and six flowers. In the regions where Indian Buddhism was accepted, it was able to be easily reproduced, and broadly distributed, and thus it became the most representative holy tree in Buddhism. From the perspective of tree shape and nature, F. religiosa is in line with the Buddhist spirit of saving those in need with mercy and redeeming mankind, and figuratively shows that perfection can be attained like the fruit of Bolisu. Chinese Buddhism had adopted highly symbolic plants for a long period time as a means to spread the same belief and doctrines as Indian Buddhism. As a result, since there were only limited areas suitable for the growth of F. religiosa in China, borrowed Bolisu trees including T. miqueliana, T. mandshurica and T. amurensis and other plants such as F. virens Ait. var. sublanceolata, G. biloba and M. alba were also planted as a substitute in most regions, having been given with symbolism and belief as Bolisu. This was a type of acculturation, and the phenomenon was not limited only in China, but similar signs were observed in Korea. The difference between China and Korea was that G. biloba was excluded from the substitutes for Bolisu in Korea.

Notes

In general, 12 species are known as a heaven flower, but in terms of scientific name, there are only 10 species including Nelumbo nucifera, Nymphaea lotus, N. stellata, N. pubescens, Michelia champaca, Hiptage benghalensis, Jasminum sambac, J. officinale, Erythrina indica, and Lycoris radiata (Park. 2012).

According to 『Sagi(史記)』 “Wonjijong(元至正) 25(A.D. 1365), Owang(吴王) Juwonjang(朱元璋) ordered civilians to plant Morus alba and Flax.” At that time, Baengma temple had to planted Morus alba and Flaxin. It is highly likely that Baengma temple Morus alba was planted during this period.

The 10th year of Donghan-Yungping(A.D. 67), the Buddhist monk in India gahyommadeung and chukppomnan comed here eight years later built the Baengma temple. After making them live there, 『Chapter 42 scriptures ((四十二章經)』 translated the first volume. Later, it gradually declined and was restored in the Tang Dynasty, but now there is only one temple tower (13 floors). The temple of the same name Jangan(長安) • Namgyong(南京) • Hyongju(荊州) etc known to exis [Baektto Encyclopedia].

多羅樹(Borasus flabellifer), a symbol of the Sutra tree, is also added here, which is regarded as the four Holy trees.

‘Bori’ in Chinese is Boje(菩提) means ‘wisdom of clarity’, which translated from the Sanskrit word ‘Bodhi’. However, in South Korea, it is pronounced ‘Bori’ because of its poor sense of language. As a result, ‘Bojesu tree’ became ‘Borisu tree’, in order to distinguish the original ‘Borisu tree’ in South Korea, it has became to ‘Borija tree’.