Relationship Satisfaction and Emotional Change between Parents and Children through the Agro-Healing Program

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

This study was conducted to investigate the effect of an agro-healing program on the relationship satisfaction and emotional change between parents and children.

Methods

We sent an official letter to D Office of Education with information and recruitment for the agro-healing program. Then D Office of Education has sent the official letter to elementary schools under the jurisdiction to recruit parents who were willing to participate in the programs with their children. The subjects were recruited by order of application, and 27 families participated, but 20 parent-child teams who attended all sessions and fully participated in the program were ultimately selected. From October 12 to November 16, 2019, a total of 6 sessions of the programs were held once a week at a care farm in Gyeongsangbuk-do. In the morning, they participated in a program that utilizes the resources of plants and animals in the care farm, and later participated in an indoor horticultural program in the afternoon.

Results

In the parent-child relationship satisfaction test, it was found that communication was significantly increased after participating in the agro-healing program (p = .047). There were no statistically significant changes in the sentence completion tests written by the children, but their potential perception or attitude towards their parents changed more positively than before according to the content of the sentences.

Conclusion

The agro-healing program could strengthen the relationship between parent and child by improving the parent-child relationship satisfaction and children’s emotional attitude towards their parent.

Introduction

Parents are the ones with whom children build their first human relations within the family that is their first society. It is a commonly known fact that parents have a significant impact on children’s development. In other words, parent-child relationship is the most fundamental human relations, and the first relationship built by the children (Chung, 1988). Parent-child relationship is the most fundamental and close relationship in children’s socialization process, and communication as a means to build and maintain this relationship is an important element in analyzing parent-child relationship as a verbal interaction (Kim, 1996).

As building human relations based on mutual understanding requires smooth communication, so does parent-child relationship. Communication is the most important medium that strengthens or weakens parent-child relationship within the family and performs a key role in human relations by conveying attitudes, thoughts, affection, ideas, etc. (Thomas, 1977). Parents must build a relationship with their children based on active communication and understanding. Children consider their relationship with parents favorable when there is active communication at home, which makes them trust their parents and become more open, thereby showing smooth psychological growth and development (Kim, 2003).

However, as the percentage of dual-income couples is increasing in the modern society, the hours for parent-child communication are gradually decreasing. According to the 2018 data by Statistics Korea (2018), 46.3% of married households are dual-income families, showing a 1.7%p increase year on year. 4.407 million households are married with children under the age of 18, and 51.0% of them are dual-income households, showing a 2.4%p increase year on year. The overall percentage of dual-income families with children has increased, and the increment of dual-income families with children aged 7–12 was the highest with 2.9%p. As proved by this statistical data, the increase in dual-income households or both parents working is a poor condition for parents and children to spend enough time and have smooth communication.

One of the main concerns dual-income parents have in educating and raising their children is the communication problem due to lack of time spent with children, which may even result in the children’s delinquency (Kong, 2009; Lee, 2012). To raise children healthy, it is important for parents to not only spend more time with their children but also have high-quality interaction with them within the given time (Kim, 2009).

According to the Rural Development Administration, agro-healing (or care farming) is defined as ‘using farming to provide care’, and it refers to ‘industries or activities that promote psychological, social, cognitive and physical health of the people using agricultural/rural resources or related activities and outputs’ (Gim et al., 2013). European countries have already established the concept, purpose, scope, and target of care farming, and policy support for care farms is already activated at the national level, indicating that care farming has established itself as a major field of the agricultural industry. Care farms officially provide new therapeutic resources for schools, communities and hospitals, while also giving emotional stability to the participants and contributing to increasing farm income (Dessein and Bock, 2010; Di lacovo et al., 2009; Hine et al., 2008).

Recently, the agricultural trend in Korea is also expanding to agro-healing that combined national health and rural experience beyond just tourism agriculture. Agro-healing, which refers to agricultural activities using farm landscapes and resources to improve physical and mental health of people today, is actively studied in terms of application in Korea, led by the Rural Development Administration (Kim, 2019). Jeong et al. (2020) examined the different effects of agro-healing and discovered that agro-healing had active therapeutic effects on psychological and emotional variables such as stress, depression, and self-esteem regardless of age. Moreover, doing various five-senses activities in wide and unstandardized spaces such as care farms had better effect on reducing children’s daily stress than small and standardized spaces, thereby helping their emotional development (Kim and Koo, 2019). Even for adults, visual landscape elements and walking activities in wide open care farms instead of indoors relieve tension, and care farming activities lower cortisol, which is a stress hormone, thereby showing positive effects on both parents and children (Jang et al., 2019). Healing programs in care farms mostly use plants, animals, rural environments, and landscapes that can be commonly encountered due to the nature of the environment. Horticultural activities can promote internal change in parents and children, and the life cycle of plants enable parents to newly find the way in which they treat their children (Choi and Seo, 2007). Moreover, horticultural activities including comfort and stability that can be found in nature and plants may broaden the common ground of parents and children, relieve conflicts and stress between them with communion based on cooperative work, and further cement their relationship.

Therefore, this study examines the parental satisfaction with parent-child relationship and children’s emotional change using the characteristics and purpose of agro-healing. It examines how horticultural activities and agricultural experiences using care farm resources affect changes in parent-child relationship and perception based on mutual understanding by activating parent-child communication and having them participate in the program together.

Research Methods

Subjects

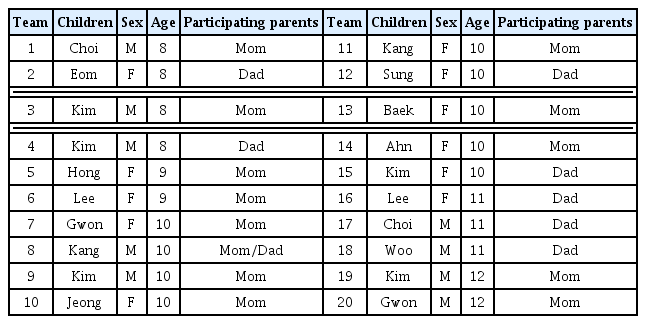

To recruit the subjects, the department to which the researchers belong sent an official letter to D Office of Education with attached information and recruitment file for the agro-healing program. Then D Office of Education sent the official letter to elementary schools under the jurisdiction so that they were delivered home for parents to apply if they were willing to participate. The subjects were clearly notified of the research purpose before the program and were to submit the consent for use of personal information. The subjects were recruited by order of application, and 27 families participated. Among them, 20 parent-child teams who attended all sessions and fully participated in the program as well as the pretest and posttest were ultimately selected as the subjects. There were more mothers participating than fathers (13 mothers, 8 fathers), and there were 4 children aged 8, 2 children aged 9, 9 children aged 10, 3 children aged 11, and 2 children aged 12. Compared to other ages, 10-year-old children showed a high rate of participation (Table 1).

Methods

Program design

The Rural Development Administration defined agro-healing as all activities for physical and emotional healing in care farms (Gim et al., 2013). In the agro-healing program, both parents and children showed satisfaction with gardening activities, and cooking with agricultural products harvested from the garden provided a positive synergy to the happiness and emotional intelligence of parents and children (Lee at al., 2020). Based on previous literature, this study can give an operational definition of agro-healing as activities carried out to promote relationship satisfaction and emotional stability of parents and elementary school children by designing an agro-healing program based on horticultural activities using elements such as animal resources, plant resources, landscape, and farm work in a care farm. Therefore, we designed a farm experience program for the morning and a horticultural program using plant resources in the farm for the afternoon. The program was carried out in total 6 sessions, comprised of activities using the farm landscape, experience centers and farm resources such as Korean native cattle, wildflowers, agricultural products, succulent plants, rice paddies, etc. This program was to achieve empathy and communication with the participation of both parents and children, as well as to seek emotional stability by improving the individual quality of life for parents and children (Son, 2012).

The specific sessions of the program are as follows. In the morning of Session 1, there was an orientation to introduce the farm and use the cattle, which is the farm resource, for cart riding and cattle feeding. In the afternoon of Session 1, the subjects introduced themselves to build rapport and decorated photo frames with pressed flowers. They put photos of themselves or their family in the frame embroidered with beautiful pressed flowers to increase self-esteem and love for their family. In the morning of Session 2, the parents and children spent time to put up a tent and enjoy the view of the farm. In the afternoon, they transplanted the plants growing in the farm to small pots and had conversations about the things that give them a hard time. They could think and realize that, even though the plants are transplanted into a smaller space, they can still produce flowers if they are well managed; and like-wise, the things that give them a hard time can also turn their inner self into a beautiful person by well managing and overcoming them. In Session 3, they harvested sweet potatoes they can cooperate in the farm, after which they participated in succulent art using a door frame in the theme of ‘Open the door to your heart’. They went into the greenhouse where succulent plants are growing and collected two types of the plants, and then decorated the door frame using adhesive soil. The parents and children could exchange various trivial questions they had about each other while decorating the door, leading them to open up to each other. In Session 4, the subjects participated in archery and had a great time playing, after which they collected different plants in the farm and planted them together in the theme of one family. In Session 5, they participated in rice field boat riding, and then made a wish box with flowers that gave a sense of achievement to both the parents and children, which they talked about with each other based on the results. In Session 6, they picked apples in the morning and made homemade cheong (fruit preserve) using the applies in the theme of a positive future for the family. The subjects could realize that, as homemade cheong needs some time to mature, the parents and children can communicate while making cheong together and repeatedly spend time together to become more solid in their family relations (Table 2).

Program implementation

Total 6 sessions of the agro-healing program were carried out with children aged 8–13 and their parents at G Care Farm (or Healing Farm) in Gyeongsangbuk-do every Saturday from October 12 to November 16, 2019. Each session was 4 hours long from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. The morning session was from 11 a.m. to 12 p.m., comprised of healing activities and experiences in the farm, after which the subjects had lunch and some free time in the farm for an hour and a half from 12 p.m. The afternoon session was from 1:30 p.m. to 3 p.m., and the subjects participated in activities using various horticultural products in the farm and took home the results they produced every session.

Assessment tool

(1) Parent-child relationship satisfaction

To examine whether parent-child relationship improved after the program, we used the parent-child relationship satisfaction scale analyzed by Byun (1999) on the parents. This test is divided into three categories: endopsychic aspect (8 items), relationship aspect (12 items), and communication aspect (10 items). They are comprised of total 30 items, with higher scores indicating that the parents relatively perceive high relationship satisfaction with their children. A Likert scale is used to give 5 points to positive items and 1 point to negative items, ranging from minimum 30 to maximum 150 points.

This study conducted the parent-child relationship satisfaction test on the parents twice, before and after the program, and the reliability of the tool was Cronbach’s α.857 and thus reliable.

(2) Sentence Completion Test (SCT)

For the children, we used the Sentence Completion Test (SCT) for children. The SCT is a test for respondents to complete multiple incomplete sentences however they want, and it is developed from the word association test. It is comprised of total 33 items, and only the subject and verb of each sentence are provided, and the respondents are to complete the sentences however they want. Tendler suggested that the SCT can distinguish the diagnosis of accident response and emotional response, and Rohde stated that it is effective in fundamentally determining the perception and inner side of the respondents that are difficult to express or reveal through a direct conversation (Choi, 2010; Lim, 2011). Accordingly, despite the diverse fields of writing, this study measured the changes in children’s thoughts and emotions toward their relationship with parents through the SCT. The test was taken twice, before and after the program, to examine the children’s perception changes toward their parents. For analysis and assessment of the text, we made revisions considering the criteria for quantitative and qualitative assessment of ‘Basic Academic Skills Assessment: Written Expression (Kim, 2008)’. The sentences were scored with focus on written expression among the writing assessment criteria with the advice of early childhood education specialists, and 1–5 points were given to total 4 categories: vocabulary, expression, sentence organization, and content (Table 3).

There are 13 categories according to the classification criteria of interpretation in the SCT, but this study only examined the ones relevant to family relations such as attitude toward the mother, attitude toward the father, attitude toward the family, and attitude toward relatives. Moreover, we added items that reveal the child’s emotional aspect of parents in items such as attitude toward negative things and attitude toward positive things. Based on the detailed criteria for assessment of written expression, we examined the change in emotional expression of the children toward their parents through the sentences they wrote.

Data analysis

Data in this study was analyzed as follows using IBM SPSS Program(19.0). The Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to assess the reliability of the scale by internal consistency, and the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to analyze whether the measured sample data has a normal distribution. We also analyzed parents’ relationship satisfaction with children and children’s perception change in the relationship with parents with the paired sample t-test.

Results and Discussions

Normality test

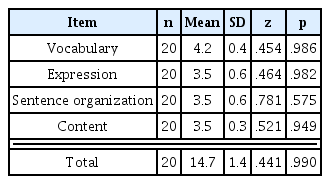

The one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine whether the collected sample data has a normal distribution. The values measured in the parent-child relationship satisfaction test are the endopsychic aspect (p = .867), relationship aspect (p = .735), and communication aspect (p = .820), showing a normal distribution with p = .973 for the total mean 115.8 (SD = 13.8) (Table 4). The values measured in the SCT are vocabulary (p = .986), expression (p = .982), sentence organization (p = .575), and content (p = .949), showing a normal distribution with p = .990 for the total mean 14.7 (SD = 1.4) (Table 5). Therefore, the parametric test was conducted for both parent-child relationship satisfaction and SCT in the mean comparison before and after the program.

Mean difference before and after the program

Parent-child relationship satisfaction

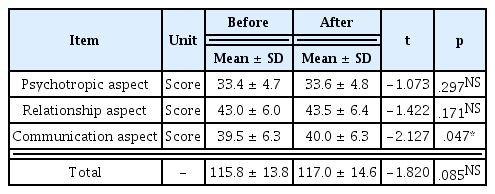

To determine the effects of a healing program carried out in a care farm on improving parent-child relationship, we measured parent-child relationship satisfaction of parents before and after the program (Table 6). The mean was 115.8 (SD = 13.8) before the program but 117.0 (SD = 14.6) after the program, showing no significant change (p = .085). However, by sub-item, the endopsychic aspect was 33.4 (SD = 4.7) before and 33.6 (SD = 4.8) after (p = .297), and the relationship aspect was 43.0 (SD = 6.0) before and 43.5 (SD = 6.4) after (p = .171), showing no significant change, but the communication aspect was 39.5 (SD = 6.3) before and 40.0 (SD = 6.3) after, showing a significant increase (p = .047). This is similar to the results that, after a mother-child healing program using garden products, the open communication between parent and child improved, which also significantly reduced the daily stress of the mother and child (Lee, 2004), and that doing horticultural work together with a shared goal helps learn how to build relationships and improve communication skills and interpersonal relations (Morgan, 1993). Moreover, agricultural activities not only help the participants feel the joy of cultivating various crops and obtain knowledge about agriculture, but also help improve relationships by recovering sociality and facilitating generational communication while spending time with family (Lee, 2012).

Sentence Completion test (STC)

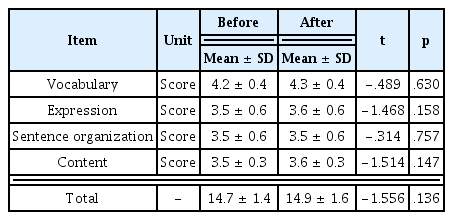

For the children, the SCT was conducted before and after the program (Table 7). The mean was 14.7±1.4 before the program but 14.9 (SD = 1.6) after the program, showing no significant change (p = .136). Even by sub-item, vocabulary was 4.2 (SD = 0.4) before and 4.3 (SD = 0.4) after (p = .630), expression was 3.5±0.6 before and 3.6 (SD = 0.6) after (p = .158), sentence organization was 3.5 (SD = 0.6) before and 3.5 (SD = 0.6) after (p = .757), and content was 3.5 (SD = 0.3) before and 3.6 (SD = 0.3) after, also showing no significant change (p = .136).

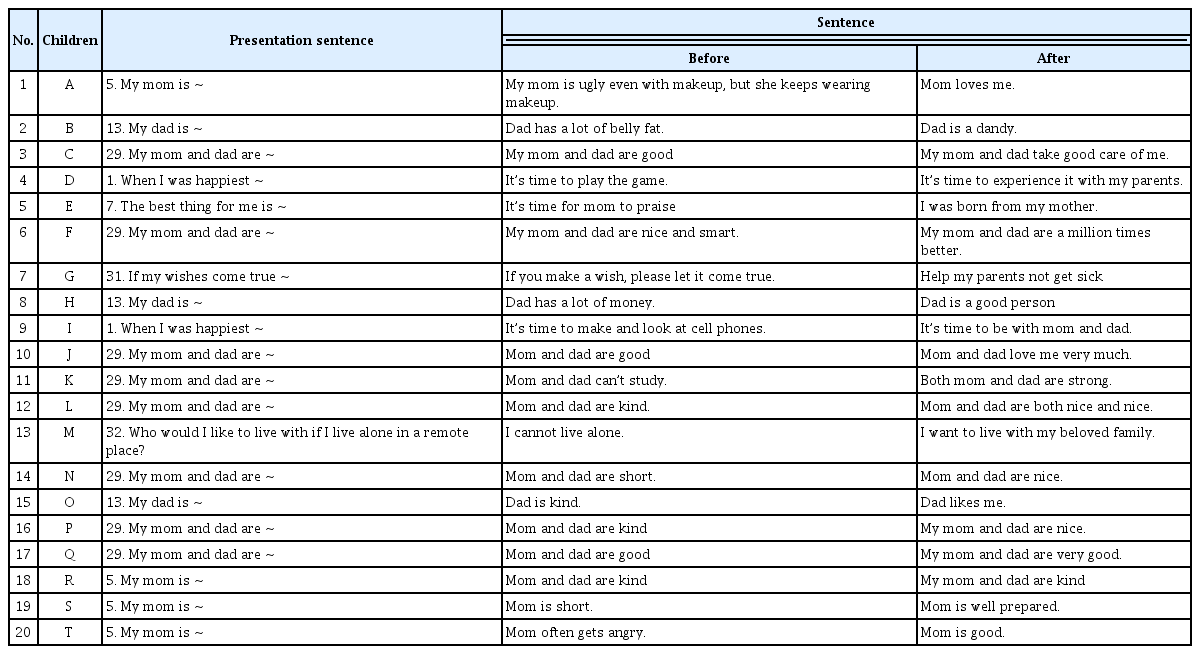

A few of the sentences completed by the subjects showed the following changes. Subject A wrote “My mom is ugly even with makeup, but she keeps wearing makeup” before the program, but wrote “My mom adores me” after the program. Subject B wrote “My dad has a big belly” before, but wrote “My dad is cool” after. Subject C wrote “My mom and dad are nice” before, but wrote “My mom and dad take good care of me” after. As such, the children who had been giving negative or indifferent responses about their parents showed a change in perception about the relationship with their parents after the program in a positive direction (Table 8).

Regarding the difference in the quantitative and qualitative assessment of the SCT, the responses and sentences written by the subjects when they participated in the program tended to show an aggressive aspect in the relationship with parents, but the change was not consistent among the subjects, and generally showed a little difference among many subjects. Moreover, there may have been a problem in the method of communication even if there were parent-child interactions, or there may not have been enough time to deeply understand the differences. Sin (2002) claimed that parents who communicate with their children in a criticizing, judgmental way cause the children to face many internal conflicts in expressing their emotions, and Woo (2009) argued that dysfunctional communication exerts a negative effect on children such as depression and problem behavior. However, gardening activities have a highly positive effect on children’s emotional development (Han, 2014; Kwack, 2004; Jeong, 2005), enabling them to feel psychological stability by communing with plants (Ulrich, 1984). As such, agricultural programs raised the awareness about building intimacy within the family and facilitated family conversations (Chu, 2014), while also making the body and mind healthy and promoting communication, which is the key function of care farming (Seo et al., 2017). Even though this was proved by this study, parents’ endopsychic and relationship aspect and children’s emotional change may not have been significant due to lack of time for sufficient, healthy communication.

Conclusion

This study examined the parent-child relationship satisfaction and emotional changes through the agro-healing program with children aged 10–12 and their parents. The agro-healing program in this study was designed with total 6 sessions using the farm resources and experience centers such as rural landscape, Korean native cattle, agricultural products, wildflowers and succulent plants based on horticultural activities in which both parents and children participate based on theoretical background. The subjects, comprised of parents and children, showed a significant improvement in parent-child communication by participating in the agro-healing program (p = .047). There was no statistically significant change in the SCT written by the children, but the comparison of the content of the sentences in qualitative assessment proved that the children’s potential perception about their parents changed positively compared to before. There is a difference in the quantitative and qualitative assessment of the SCT because the change is not consistent among the subjects due to individual differences, and some subjects merely showed insignificant differences. There may have also been a problem or unfamiliarity in parent-child communication. Additional research can be attempted on the fact that there were no significant results in parents’ endopsychic aspect and relationship aspect, with focus on the internal change of parents after communicating with their children. This will bring more effective emotional change in parent-child relationship satisfaction through the agro-healing program.