Revalidating the Factor Structure of Types of Horticultural Therapy Activities with Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Horticultural activity is one of the most basic elements of horticultural therapy, which brings about therapeutic effects for participants through various plant-related activities. The main objective of this study was to verify the results of previous research, which suggested six types of activities from the exploratory factor analysis.

Methods

To meet the purpose of this study, a questionnaire was designed to determine the preferences for 6 types of the horticultural therapy activities. The survey was conducted on 703 people from March 7 to June 20, 2019. The data of 674 cases were used into the final analysis, excluding unreliable responses. Descriptive statistics, and reliability analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25, and confirmatory factor analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Amos 21.

Results

First, horticultural therapy activities were classified into 6 types from the exploratory factor analysis, as conducted in previous research. The confirmatory factor analysis provided that the fit of the final model was satisfactory with χ2 = 1,300.590 (p < .001), RMR = .045, GFI = .876, RMSEA = .062, NFI = .914, TLI = .905, CFI = .914.

Conclusion

This result revalidated that the mode with 6 types of horticultural therapy activities from previous research is appropriate criteria for the classification of horticultural activities. The model could be used to design more systematic horticultural therapy programs that meet the needs or circumstances of the subject, or that are suitable for necessary therapeutic intervention methods.

Introduction

Since Benjamin Rush, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, announced that gardening helps recover patients with mental diseases (Rush, 1812), the therapeutic effects of horticultural activities have been pointed out, after which agriculture and gardening activities have been included in therapy programs at psychiatric hospitals (Detweiler et al., 2012). As such, the therapeutic effects of horticultural activities carried out and expanded in hospitals included stress relief, increased happiness, participation in social life and vocational rehabilitation, and research findings about therapeutic intervention of horticultural activities began to be announced (Söderback et al., 2004). In addition, horticultural therapy as an intervention mediated by nature is receiving attention in preventive and alternative medicine as a complementary and alternative therapy that can be easily applied to not only patients but also people in general like college students or the elderly, or in special cases such as caregivers of dementia patients or children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Jo et al., 2019; Kamioka et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Yun et al., 2020).

Contacting or building a relationship with nature restores attention of humans, relieves stress, creates a pleasant mood, and promotes psychological happiness (Berman et al., 2008; Van den Berg and Custers, 2011). Horticultural activities are activities related to plants or gardens, and they bring the effects of psychological and emotional therapy or physical rehabilitation through the inborn intimacy humans feel toward nature (Bassi et al., 2018).

Hefley (1973), who referred to horticulture as a therapeutic tool for plant or garden-related activities, proposed 6 types of activities: ‘Arts and Crafts (A type)’ making indoor crafts like decorations with artificial flowers, collages using related materials, accessories using seeds or dried flowers, or outdoor crafts like garden decorations or furniture; ‘Group Activities (B type)’ including activities such as garden bingo or flower name quiz, looking at pictures and talking, listening to related myths and legends, and watching movies or slide shows; ‘Excursions (C type)’ including botanical gardens, gardens, parks, exhibitions and materials collection; ‘Plants-Indoors (D type)’ including flower arrangement, corsage making, terrarium, dish garden, indoor plant cultivation and hydroponics; ‘Plants-Outdoors (E type)’ including flower beds, vegetable and herb gardens and garden management; and ‘Related Fields of Study (F type)’ learning about plant-related diseases and pests, soil and small animals in gardens. Since horticultural therapy has been introduced in Korea, the types of horticultural activities were classified into minimum three to maximum seven types depending on the characteristic and applied to research (Choi, 2003; Kim, 2007; Lee et al., 2009; Park et al., 2016; Suh and Lee, 2004). Accordingly, previous research conducted surveys on horticultural activities, analyzed the characteristics of the activities based on factors derived from exploratory factor analysis, decided on the factor names depending on the characteristics of each factor, and established the basic constructs (Kim et al., 2018). As a result of previous research, horticultural therapy activities were categorized into 6 types: ‘Indoor Gardening (IG)’, ‘Outdoor Gardening (OG)’, ‘Art and Cooking (AC)’, ‘Feeling Direct Nature (FD)’, ‘Sharing Indirect Nature (SI)’, and ‘Nature Study and Collecting (NS)’.

Factor analysis is a statistical method that analyzes correlation among variables by conducting a survey through abstract constructs, extracts common factors and contracts them into key factors. This is classified by purpose into exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA; Choi and You, 2017). The difference between use of EFA and CFA is whether it has an exploratory character, conducting analysis based on data without theoretical confidence, or it has a confirmatory character, confirming the factors by analyzing the model based on theoretical grounds (Park et al., 2014). As such, confirmatory factor analysis is a theory-oriented analytical method as a theory validation process, confirming the constructs of latent variables and research models depending on the theoretical background or results of previous research (Choi and You, 2017).

This study is to validate the basic constructs derived from previous research through confirmatory factor analysis and revalidate and generalize the research models derived from the results of previous research.

Research Methods

Theoretical background

To revalidate the factor structure of six types of horticultural activities proposed in the study results by Kim et al. (2018), we selected the activities in each type as the variables and formed a survey. Previous research structuralized the factors through exploratory factor analysis and came up with brief characteristics of each type, and this study derived related activities based on these characteristics from previous studies (Choi, 2003; Hefley, 1973; Kim et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2006) as shown in Table 1.

Subjects

The subjects of this study are undergraduate and graduate students attending 12 universities in Korea due to the regional limitations of the primary study. The subjects were selected using effect size .05, alpha-error .05, power .95, 18 measurement items, and a two-tailed test using G Power 3.1 Program in the conditions of multiple regression analysis. The results showed that there were 607 minimum samples, and considering the generally applied dropout rate, we selected 700 subjects. The final questionnaire was retrieved from 703 subjects, and the data of 674 subjects were used in the final analysis excluding poor responses.

Methods and items

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (GIRB-A19-Y-0007) of Gyeongsang National University in March 2019. The survey was conducted from March 7 to June 20, 2019 after the approval. It was conducted offline, and we obtained consent from the participants in the recruitment process before the survey and also provided a certain reward for the participants after the survey.

The survey was comprised of items to determine the general characteristics of the participants such as year of study, major, age, gender, and area of residence on a nominal scale. Six activities for each type of horticultural therapy activities were selected, adding up to total 36 horticultural therapy activities, the preference of which is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Least preferred, 2 = Not preferred, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Preferred, 5 = Most preferred).

Statistical analysis and research model

Statistical analysis

Frequency analysis, descriptive statistics and reliability analysis were conducted on the survey data using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Moreover, to verify the factor structure of types of horticultural activities, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using IBMSPSS Amos 21.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis, which can be conducted to validate the theories in the results derived by exploratory factor analysis, is a theory-oriented validation method assuming that each measured variable is correlated with only the relevant factors based on strong theoretical background or previous research. Confirmatory factor analysis undergoes additional tests such as goodness of fit test to test whether the covariance matrix of data is suitable for the research model, as well as convergent validity and discriminant validity tests, making it a conservative method compared to exploratory factor analysis (Choi and You, 2017). To test the fit of the research model we examined absolute fit indices such as χ2 (CMIN), root mean square error of approximation (RMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness of fit index (GFI) as well as incremental fit indices (CFI, NFI, TLI) and parsimonious fit indices (PGFI, PNFI). To analyze convergent validity, we used standardized factor loadings, significance, average variance extracted (AVE), and construct reliability (CR). This study revalidated the classification model of horticultural therapy activities by conducting confirmatory factor analysis on factors derived by exploratory factor analysis and tested internal consistency of the types through reliability analysis.

Results and Discussion

Demographic characteristics

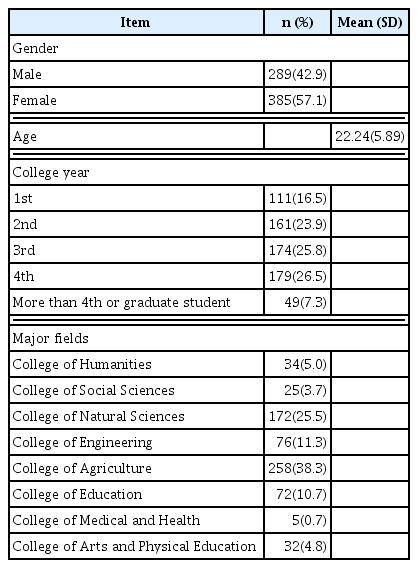

The demographic characteristics of the subjects are as shown in Table 2. There were 385 female students (57.1%) and 289 male students (42.9%). The average age was 22.24, and most of them were in their 4th year (179, 26.5%), followed by 3rd year (174, 25.8%), 2nd year (161, 23.9%), 1st year (111, 16.5%), and higher than 4th year or graduate students (49, 7.3%). Most of them were majoring in agriculture (258, 38.3%) followed by natural sciences (172, 25.5%), engineering (76, 11.3%), education (72, 10.7%), humanities (34, 5.0%), arts and physical education (32, 4.7%), social sciences (25, 3.7%), and medicine and health (5, 0.7%).

Confirmatory factor analysis

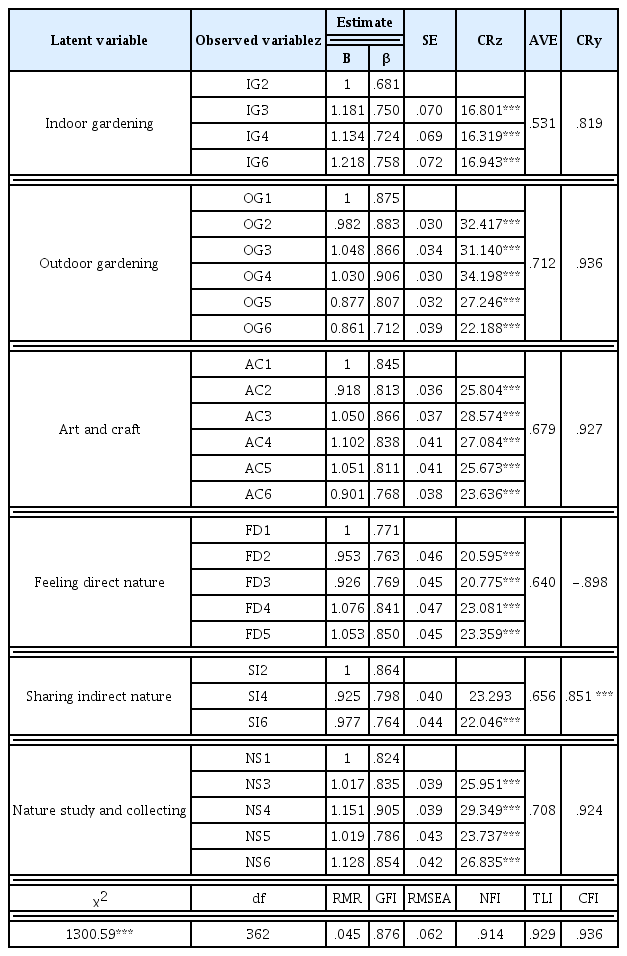

The path of setting six types of horticultural therapy activities as latent variables and then structuralizing and confirming each activity as the observed variables was all significant at the level of .001. More specifically, construct validity was confirmed with standardized coefficients all higher than .5, and a suitable level of convergent validity was also confirmed with AVE higher than .5 and construct reliability (CR) higher than .7.

The fit of the initial model constructed according to the first theoretical background was χ2 = 2,568.87 (p < .001), RMR = .064, GFI = .802, RMSEA = .071, and incremental fit indices NFI = .865, TLI = .883, CFI = .892 (Table 3). The results show that the model constructed according to the initial theoretical background is statistically significant. However, in the fit values of the model confirmed in the structural equation modeling, RMSEA was smaller than .08 and thus favorable, but in other fit values it was lower than the criteria for fitness. To improve the fit of the model, the analysis was conducted after excluding ‘Dyeing fingernails with garden balsam (FD6)’, which is considered to hinder convergent validity due to low factor loading and standardized coefficient.

Results from a confirmatory factor analysis of the horticultural activity preference (HAP) questionnaire about model fitness

As a result, the fit was improved to χ2 = 2,393.22 (p < .001), RMR = .055, GFI = .809, RMSEA = .071 for absolute fit indices, and NFI = .872, TLI = .889, CFI = .898 for incremental fit indices (Table 3), but except for RMSEA that was smaller than .08 and thus favorable, other fit values were all lower than the criteria for fitness. Accordingly, to additionally improve the fit of the model, the analysis was conducted after excluding ‘Viewing and discussing plant-themed art (SI5)’ and ‘Watching and discussing related films or videos (SI3)’, which seem to hinder discriminant validity with cross-loading higher than .4 in the exploratory factor analysis. The fit of the model excluding factors that hinder discriminant validity was χ2 = 1,928.353 (p < .001), RMR = .053, GFI = .841, RMSEA = .067 for absolute fit indices, and NFI = .889, TLI = .905, CFI = .914 for incremental fit indices (Table 3). By eliminating factors hindering discriminant validity, incremental fit indices were improved at an adequate level excluding NFI, but the absolute fit indices were still confirmed to be unfit excluding RMSEA. Accordingly, analysis was conducted excluding ‘Picking wildflowers and making pressed flowers (NS2)’ in Factor 1, IG1, IG5 in Factor 5, and SI1 in Factor 6 in which the factor loadings were lower than 0.6 in the exploratory factor analysis. The fit of the model was satisfactory, with χ2 = 1,300.590 (p < .001), RMR = .045, GFI = .876, RMSEA = .062 for absolute fit indices, and NFI = .914, TLI = .905, CFI = .914 for incremental fit indices (Table 3).

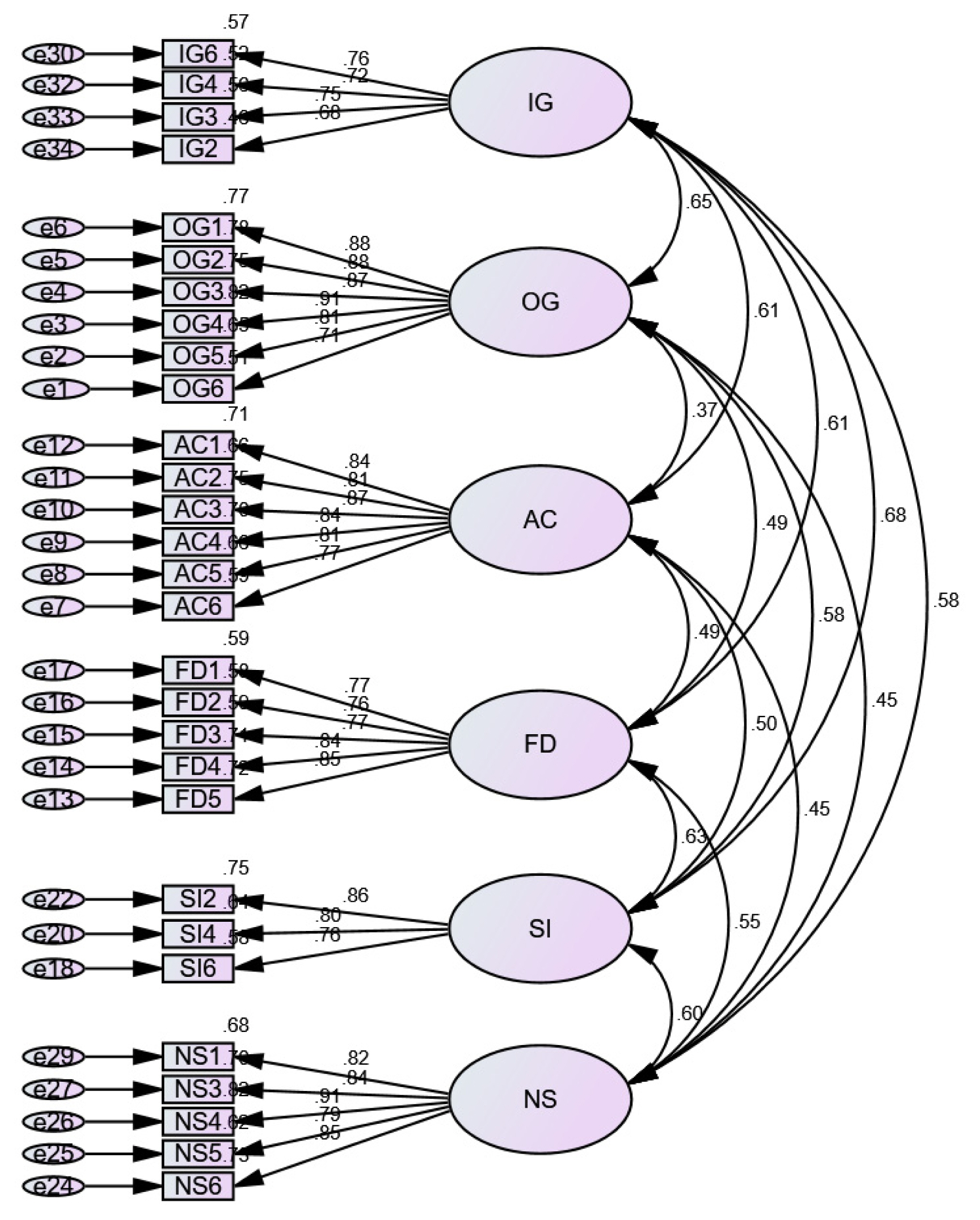

Accordingly, the final path model used is as shown in Fig. 1, and the factor loadings among variables that explain each factor are .68–.91, showing moderate/high degrees of correlation, and the correlations of each factor are .37–.68, showing low/moderate degrees. As a result of the confirmatory factor analysis of the final model, it was found that the paths that lead from latent variables to observed variables in the 6 types of activities were all significant at the level of .001 as shown in Table 4. This result shows that the observed values finally selected best explain the latent variables set by previous research, and the fact that the correlation among latent variables were moderate to low implies that factors derived from exploratory factor analysis in previous research have unique characteristics different from other latent variables. However, the correlation coefficient among latent variables was higher than .6 because horticultural activities basically share the fact that they are all mediated by plants, and that there is a similar connection among the factors. To begin with, ‘indoor gardening’ and ‘outdoor gardening’ ( Φ=.65) involve activities such as growing, tending and taking care of plants, classified as ‘cultivation activities’ or ‘growing’ in studies by Kim (2007) and Lee et al. (2009). As mentioned by Kim et al. (2018), there is not much difference between indoor and outdoor gardening aside from where the activities take place, which is why the correlation coefficient showed a moderate degree. Moreover, ‘indoor gardening’ and ‘sharing indirect nature’ (Φ=.68) that showed the highest correlation coefficient between the latent variables were comprised of activities sharing or selling the harvested horticultural products after eliminating activities related to discussing or talking (SI1, SI3, SI5) among observed variables of sharing indirect nature in the process of confirmatory factor analysis. These activities are carried out in harvest, which is the last step of the process of growing and harvesting plants. Except for sharing through contact with others, which was a major characteristic of ‘sharing indirect nature’ in the study by Kim et al. (2018), they may seem as a part of ‘cultivation activities’ or ‘growing’ in studies by Kim (2007) and Lee et al. (2009). Thus, the correlation was relatively higher than that between other latent variables. Next, the correlation was relatively high between ‘feeling direct nature’ and ‘sharing indirect nature’ (Φ=.68). Unlike other types of activities, these two activities were not about directly looking after plants or creating outputs, but were obtaining positive effects by forming relationships with others or using therapeutic effects of natural contact such as appreciating and feeling plants or surrounding environment (Kim et al., 2018). These activities were classified by Suh and Lee (2004) as ‘feeling’ activities. As such, the element of ‘feeling’ shared by these two types of activities may be the cause for the fact that correlation between these two latent variables was relatively higher than that between other latent variables.

Reliability analysis

In the results of confirmatory factor analysis (Table 4), it was found that factor loadings of a few activities hindered convergent validity, discriminant validity and fit of the model, and thus reliability analysis was conducted to check the internal consistency of each factor (Table 5).

The results showed that Cronbach’s α, which is the internal consistency among activities in all factors, showed a high level of internal consistency from minimum .864 to maximum .935, and each factor seems to be well structured in each activity. However, ‘Factor 1’ and ‘Factor 2’ showed detailed items that increase internal consistency when items are deleted. First, in ‘Factor 1’, FD6 that was confirmed as an item hindering convergent validity in the exploratory factor analysis increased internal consistency when it is deleted from the reliability analysis result, from Cronbach’s α .908 to .923 after deleting. Moreover, in ‘Factor 2’, deleting ‘guerilla gardening (OG6)’ turned out to increase internal consistency. This is because while other activities in ‘Factor 2’ are comprised of forming and tending one garden, ‘guerilla gardening’ may have been perceived differently by the subjects in terms of content.

As for NS2 in ‘Factor 1’, IG1, IG5 in ‘Factor 5’, and SI1, SI3, SI5 in ‘Factor 6’ excluded from the final model of the confirmatory factor analysis, they were not the items that increased internal consistency when deleted as a result of reliability analysis. In the result of the initial model of confirmatory factor analysis before excluding observed variables, AVE was all higher than .5 and construct reliability was all higher than .7, showing that there was convergent validity, thereby hindering the fit of the model but not affecting internal consistency. Compared to the result of the confirmatory factor analysis before, the characteristics of ‘sharing indirect nature’ in which many observed variables were excluded in the confirmatory factor analysis can be derived more definitely. As previously mentioned, the activities finally selected in the confirmatory factor analysis have relatively high similarity with the activities of ‘cultivation/growing’ by Kim (2007) and Lee et al. (2009) except for the part about sharing through contact with others. Therefore, latent variables comprised of the variables selected in confirmatory factor analysis had a moderate or higher correlation with ‘indoor gardening’. However, in the results of reliability analysis, it was confirmed that items excluded from confirmatory factor analysis (SI1, SI3, SI5) are not observed variables hindering internal consistency of the latent variable ‘sharing indirect nature’ of ‘Factor 6’. This result supports that, in the ‘sharing indirect nature’ type, the ‘therapeutic effects of natural contact using media and positive effects by building relationships with others’ conceptualized as characteristics of activities by Kim et al. (2018) are important characteristics. Considering the results, for additional research on classification of six types of horticultural activities with revalidated factor structure, we suggest establishing the classification criteria by defining theoretical concepts in addition to statistical verification by determining the characteristics that serve as the classification criteria of each type of activities.

Conclusion

Horticultural activities are classified into minimum 3 to maximum 7 types by researchers, applying different criteria depending on the content of the activity. This study was conducted to structurally revalidate the study results of Kim et al. (2018) that classified horticultural therapy activities into 6 types through exploratory factor analysis. Previous research that suggested 6 types of horticultural therapy activities was the basic study that explored factors based on the classification into 7 types. Previous research was a basic exploratory study on factors that classified the types of activities and thus had limited scope of study areas and few examples of categorized activities. Thus, there were limitations in which the subjects perceived the characteristics of activities in each type. Therefore, this study intended to generalize the results by setting the scope of research to the entire nation, and conducted the survey by calculating the adequate number of subjects to secure reliability of the questionnaire constructed through a statistical method according to the increase in the number of survey items and recruiting subjects that meet these requirements. Through this process, we made up for the deficiencies of previous research and revalidated the results using confirmatory factor analysis. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis to validate the theories of constructs for factors generated as the result of exploratory factor analysis in previous research. As a result, we could confirm and validate 6 types of constructs proposed through exploratory factor analysis. This study has limitations in that, even though the survey was conducted on the entire nation to generalize the results, most of the subjects were in their 20s, which raises the need for additional research on each age group. Furthermore, the results of this study show the results of investigating preferences obtained through a survey, not preferences felt after experiencing all activities. Thus, there is a need for empirical research on whether the subjects perceive the difference in characteristics of each type as classified in this study as well as previous research, after having them experience the activities of each type through additional research. Moreover, it is necessary to establish constructs and characteristics of each type of activities proposed in previous research and set the criteria for classification of the activities. To this end, we suggest classifying the horticultural activities that were carried out into 6 types based on sufficient review of massive research data released thus far and analyzing the classified activities. By conducting basic research on horticultural activities, we can establish the characteristics and constructs of these activities used as a therapeutic tool in horticultural therapy and use them as the basic data for selecting and applying horticultural activities suitable for necessary therapeutic interventions, demands or situations of subjects in stead of applying horticultural activities indiscreetly in program planning, thereby applying more systematic horticultural therapy to the subjects.

Acknowledgements

This study excerpted parts of “Reclassification of Horticultural Therapy Activities and Development of Preference-Based Horticultural Therapy Programs Based on the Four Temperaments”, the doctoral dissertation of Yong Hyun Kim, the first author.