Development of a Competency-Based Master Gardener Coordinator Curriculum: Focusing on Public Service Rural Extension Workers

Article information

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to establish the role of master gardener coordinators and develop an education program to enhance their job competencies. To analyze and develop the new job of master gardener coordinator, we used the CBC method for curriculum development. The research findings can be summarized as follows. The analysis result of need and importance of education based on the performance level and demand level revealed 20 core competencies, which were classified into organizational education, learning by experience, individual learning, low-priority competencies for program development, with focus on the importance and need for education. The 17 courses are comprised of Eastern and Western Garden History, Understanding of Community Garden, Garden Aesthetics and Environmental Design, Master Gardener’s Mission & Management, Garden Plants, and Garden Design and Practice etc. and the curriculum is 33 hours in total. The master gardener coordinator education program was conducted on 73 rural extension workers and the curriculum was evaluated by those who completed the program. The overall satisfaction was 4.29 and 97.1% of the trainees decided that the program would help them perform their duties. The analysis result discovered that all 20 core competencies increased after the program. As a result of conducting contingent valuation to determine the value of the program, willingness to pay (WTP) per hour was KRW 33,223 and the total WTP was KRW 1.096 million, which, when multiplied by 73 participants, is approximately KRW 80.008 million. This is relatively higher than the budget used (KRW 22.943 million), indicating that the program is worth it.

Introduction

Oh (2015) reported the current state of master gardeners in South Korea and raised the need for master gardener coordinators in the US agricultural extension services as well as the need to reinforce their roles in each agency, while also suggesting the necessity of system and role in operating master gardeners and master gardener coordinators (Kwack et al., 2017).

As nature-related experiences and environment-friendly activities increased nationwide since 2000, the demand for weekend farms, ecological parks and community gardens shared by the resident community is increasing every year. As the social demand for gardens has expanded nationwide, legislations of government departments and ordinances of local governments are established to support garden and nature experience activities (Park, 2012).

However, some agricultural extension agencies such as Gyeongggi-do Agricultural Research & Extension Services, Jeju Agricultural Research & Extension Services, and Busan Agricultural Technology Center are recently receiving good response by adopting the master gardener system and curriculum of the US and Canada, but there is a gap in education level and effect due to lack of standard curriculum and operating experts (Han et al., 2017). Moreover, they are seeking ways to associate the expertise of human resources trained by the government and private organizations with job-related activities, and thus management of their expertise and competencies is becoming very important. However, there is a lack of standards about expertise required by master gardener coordinators as well as standards about the degree required for certification, related license and career experience.

Agricultural extension agencies have over 4,300 rural extension workers in nine Provincial Agricultural Research & Extension Services and 156 Agricultural Technology Centers nationwide, and they are enhancing the competitiveness of agriculture and efficiently utilizing the resources of agricultural communities through the distribution of the outcomes of research and development and the managerial innovation of agricultural enterprises. With the increasing demand for garden-related education with focus on Metropolitan City Agricultural Technology Centers, garden-related curriculums are currently being operated by 134 workers in 114 departments of total 78 agencies as of 2017, such as eight Metropolitan City Agricultural Technology Centers, three Provincial Agricultural Research & Extension Services, and 67 City and District Agricultural Technology Centers (Han et al., 2017).

To nurture Korean-style master gardener coordinators among public service rural extension workers, this study develops an education program by deriving competencies required by master gardener coordinators and selecting the most important core competencies, thereby suggesting a standard education program for agencies that provide education for master gardener coordinators such as the Rural Development Administration, City and District Agricultural Technology Centers, Korean Master Gardener Association, and private organizations.

Research Methods

Agricultural extension services and competencies of rural extension workers

Agricultural extension services are referred to as cooperative extension work. The word ‘extension’ is first used by the UK, and it means to add something to enlarge or prolong. As part of university extension education in the University of Cambridge and University of Oxford in the UK, the human, material and scientific resources of the universities were extended to general citizens, opening a public lecture for the general public instead of enrolled students. This activity was spread to the US, and the system of agricultural extension services that fully began in state universities of the US supplies technologies, mobilizes human and material resources, and embrace both public and private institutions (Kim, 2007; van den Ban and Hawkins 1996).

Agricultural extension services in Korea refer to projects designed for enhancing the competitiveness of agriculture and efficiently utilizing the resources of agricultural communities through the distribution of the outcomes of research and development and the managerial innovation of agricultural enterprises (Agricultural Community Development Promotion Act Article 2, Definitions). The scope of business is classified into six categories in Article 2 ② of the Enforcement Decree of the Agricultural Community Development Promotion Act such as supporting local agriculture aside from rural areas such as urban agriculture, and four domains of activity are set in ③ such as education and training for those about to be involved in agriculture such as new farmers, agriculture-related education and training for those living in regions other than rural areas such as cities. Article 2 ③ of the Enforcement Decree of the Agricultural Community Development Promotion Act defines the role of education and training, thereby securing legal status to supply new agricultural techniques in Korea and overseas to urban residents and farmers through education, counseling and consulting. The system is comprised of Rural Development Administration-Provincial Agricultural Research & Extension Services-City and District Agricultural Technology Center. In this system, competency development of rural extension workers that perform the role of lecturer, counselor and consultant have great significance in national agricultural extension services and agricultural development.

Kim (2006) reestablished the competencies of rural extension workers as six basic job competencies, six main behaviors, two specialized job competencies, and 33 main behaviors, designing the structure as basic and job competencies and reflecting the agricultural and rural extension environment, thereby proposing a future-oriented competency model of rural extension workers. Public service extension workers need basic, job and leadership competencies to obtain, use, share, apply and generate knowledge, and required competencies vary depending on hierarchy and job (Kim et al., 2008).

Deriving competencies of master gardener coordinators and organizing the curriculum

‘Competency-based curriculum’ has significance in promoting individual and social suitability of the curriculum and focusing on competency building of learners (Park, 2009; Saunders and Machell, 2000; Washer, 2007). The competency model systemized the competencies necessary for certain jobs or occupational groups to achieve organizational goals, and it is revised and fostered through education, training and development focused on individual behavior rather than inherited traits or motives (Harris, 1998; Jeon, 2005; Kim, 2006). Competency-based curriculum (CBC) derives courses that are directly linked to function and output with the purpose of improving work performance skills. Fig. 1 shows the process of developing CBC on master gardener coordinators for public service rural extension workers.

First, we gathered 11 public service extension workers performing tasks related to master gardeners at the Daejeon Agricultural Technology Center in July 2017 and conducted a focus group interview, through which we extracted 30 competencies of master gardener coordinators and defined their concepts.

To come up with the performance level and need for education for each competency to be used in developing the education program, we conducted a survey on 1,320 out of 4,320 public service rural extension workers in rural development agencies handling actual affairs on site, such as education, planning and general affairs, rural resources, garden and urban agriculture, rural landscaping, cultivation/stockbreeding/insects, etc. Total 926 copies of the questionnaire were retrieved, showing a 74% response rate. To examine the reliability of the collected questionnaire, we calculated the internal consistency of each item using Cronbach’s alpha, and verified the performance level and demand level by calculating the mean and standard deviation. Data was analyzed using SPSS 18.0 (for Windows). The need for education was calculated using Borich’s formula (Borich, 1980) based on the performance level of current work and demand level necessary for future work.

We conducted a survey on 30 experts related to master gardener coordinator in August 2017, analyzed the importance and need for education, came up with 20 core competencies, and classified them according to the core competency classification of rural extension workers (Kim et al., 2007).

For master gardener coordinator education that can be applied to public service rural extension workers in Korea, we collected and classified horticulture and landscape architecture curriculums in Korea, master gardener programs of the Master Gardener Association, master gardener and similar curriculums, and master gardener programs in six states of the US including Kansas. Then, we conducted a primary survey on 30 experts related to master gardener coordinator from August 2 to 6, 2017, classified courses related to competencies, and derived courses through the secondary deliberation of eight validators. Table 1 shows the positions and responsibilities of validators that participated in curriculum development.

The master gardener coordinator program was designed by categorizing the curriculums collected and 20 core competencies and courses derived with five validators specialized in gardening, and confirmed the course titles and education time after discussing the education method.

Performance assessment of the master gardener coordinator curriculum

To validate and assess the developed master gardener coordinator program, we operated the curriculum as follows. To increase expertise of each lecture, we selected lecturers recommended by the validators in each field, and sent the syllabus for each lecture and required core competencies to the lecturers via email, requesting their cooperation to develop the competencies. The program was carried out for 5 days with 73 rural extension workers from August 28 to September 1, 2017. A survey was conducted to assess the performance level and demand level to calculate the need for education before and after the program as well as the extent of competency enhancement on a 5-point scale.

To determine the effectiveness of master gardener coordinator education for rural extension workers, we measured the utility of the competency enhancement program with the willingness to pay the tuition by the contingent valuation method (CVM; Jung, 2010).

The probability model of respondents receiving master gardener coordinator education can be estimated using the probit model and logit model. In this study, the linear logit model is used to calculate the mean of maximum willingness to pay (WTP) for master gardener coordinator education (Mitchell and Carson, 2013).

The survey was conducted on 73 trainees before and after the program. For comparative assessment, we explained the purpose and content of the education as well as details of the program to 82 rural extension workers who did not receive education from Provincial Agricultural Research & Extension Services and conducted the survey. The expected WTP was set as KRW 5,000, KRW 10,000, KRW 20,000 and KRW 30,000 with reference to the tuition for a similar curriculum registered on the website of Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). Total budget for this education was calculated to compare the tangible value of the master gardener program that is to be calculated in the virtual valuation and the budget invested by Rural Human Resource Development Center.

Results and Discussion

Development of the master gardener coordinator competency model

To develop a master gardener coordinator education program, we conducted a competency diagnosis survey on 30 public service rural extension workers in charge of master gardener coordinator or related affairs recommended by Provincial Agricultural Research & Extension Services, Korean Master Gardener Association, and DACUM (Developing A Curriculum) Panel. The general characteristics of the respondents are as follows (Table 2).

To test the reliability of the competency diagnostic assessment of master gardener coordinators, we calculated internal consistency of each item using Cronbach’s alpha. The result showed that the reliability coefficient was .924 for the importance assessment of core competencies, .984 for performance level assessment, and .914 for demand level assessment. In other words, all had high reliability that exceeded .9 and showed consistency among items.

As a result of comparing core competencies in terms of performance level and demand level of master gardener coordinators, it was found that all core competencies showed higher scores for demand level than performance level, showing a statistically significant difference (p < .001). ‘Student identification and management’ had the performance level of 2.77 (SD = 1.25) and demand level of 4.32 (SD = 0.34), showing higher demand level, and ‘counseling and interview competency’ had the performance level of 2.60 (SD = 1.19) and demand level of 4.20 (SD = 0.55), showing higher demand level. ‘Communication and negotiation’ also had the performance level of 2.83 (SD = 1.15) and demand level of 4.23 (SD = 0.77) showing higher demand level.

As a result of assessing performance level and demand level by competency, it was found that the performance level was highest in leadership at 3.03 (SD = 0.89), promotion at 3.03 (SD = 1.00), and self-development at 3.00 (SD = 1.08), with the middle ranking of IT equipment utilization at 2.90 (SD = 0.84), master gardener course operation at 2.90 (SD = 0.95), and garden utilization at 2.90 (SD = 0.84). The demand level was high in curriculum-related competencies such as master gardener course operation at 4.63 (SD = 0.56), master gardener course development at 4.57 (SD = 0.57), and post-management of master gardener course at 4.50 (SD = 0.57), with the middle ranking of communication and negotiation at 4.23 (SD = 0.77), resource management at 4.23 (SD = 0.63), and analysis and evaluation at 4.23 (SD = 0.68).

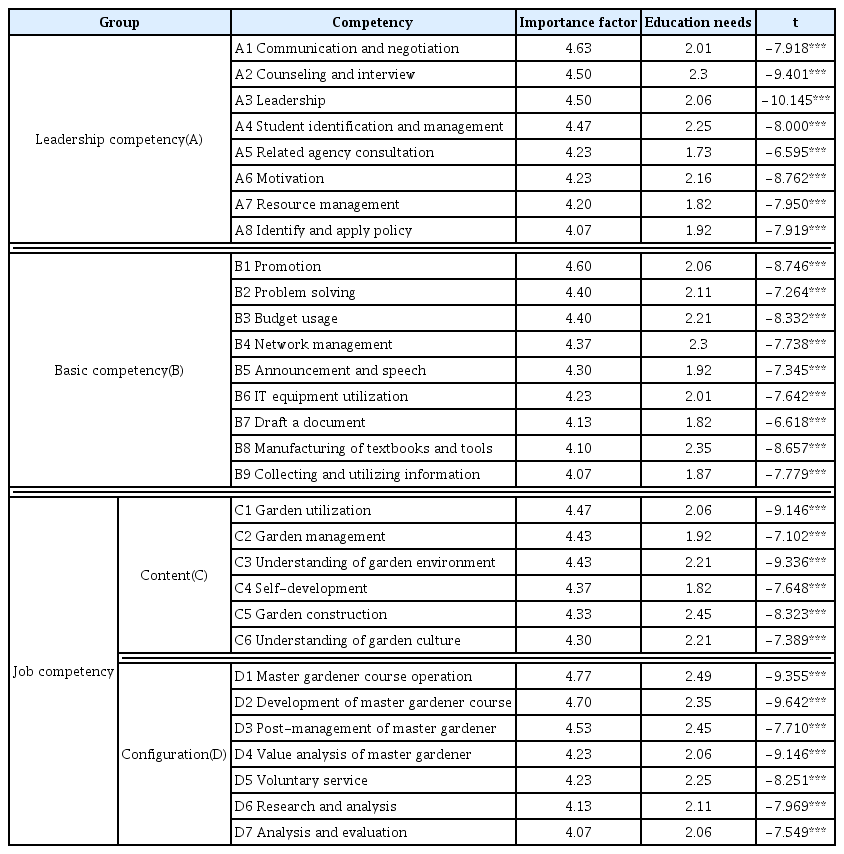

Table 3 shows the result of analyzing and comparing the performance level and demand level of need for education with Borich’s formula.

The importance was high in master gardener course operation at 4.77 and master gardener course development at 4.70, showing high importance in curriculum development and operation. On the contrary, it was low in law/policy identification and application at 4.07, analysis and evaluation at 4.07, information collection and utilization at 4.07, textbook and tool making at 4.10, document drafting at 4.13, research and analysis at 4.13, and related agency consultation at 4.23. Like importance, the need for education was also high in curriculum-related competencies, whereas it was low in administrative competencies such as related agency consultation and document drafting. This implies that the focus is on competencies that represent basic skills like analysis and administration instead of specialized competencies such as skills required by master gardener coordinators.

Development and assessment of the master gardener coordinator curriculum

As a result of collecting courses of similar curriculums first, we analyzed the landscape and master gardener curriculums that have high garden-related expertise, curriculums recommended by Korean Master Gardener Association, horticulture courses with high expertise in agricultural techniques and courses of Agricultural Technology Center, and classified them into four core competency groups: ‘leadership group’, ‘basic competency group’, and ‘job competency group (content, configuration)’. We selected courses that need specialized skills with focus on specialized competencies, and as a result organized courses focusing on garden plant management, garden design theory and practice, understanding of environmental impact assessment, garden construction theory, practice and evaluation, garden plants & pest management, Eastern and Western garden history, understanding of community gardens, garden aesthetics and environmental design, garden environment management, etc. As the competencies for course operation, we included curriculums such as volunteer activity management theory, theory and practice of volunteering, cases of counseling, curriculum analysis, engineering design and program development, curriculum operation & evaluation, cases of master gardener activities, basics of SNS utilization, etc. We excluded 10 low-priority competencies for volunteering, which is the main duty of master gardeners, from the priorities in developing the education program, such as resource management, presentation and speech, budget use and utilization, related agency consultation, document drafting, research and analysis, analysis and evaluation, information collection and utilization, law/policy identification and application, IT equipment utilization, and garden value analysis. Table 4 shows the curriculum comprised of 33 hours and 17 courses to assess the education program based on the derived courses.

Performance assessment of the master gardener coordinator curriculum

The survey results for analysis on change in core competencies are as shown in Table 5. ‘Understanding of garden culture’ increased by 1.13, showing the biggest increment, and ‘development of master gardener course’ increased by 1.01, ‘communication and negotiation’ by 0.90, and ‘student identification and management’ by 0.89. Competencies that increased moderately were ‘counseling and interview’ that increased by 0.87, ‘post-management of master gardener course’ by 0.86, ‘motivation’ by 0.86, and ‘volunteer service’ by 0.85. Core competencies with the smallest variation were ‘promotion’ that increased by 0.66, ‘problem solving’ by 0.78, and ‘self-development’ by 0.69. ‘Understanding of garden culture’, ‘development of master gardener course’, ‘manufacturing of textbooks and tools’, and ‘network management’ shared the similarity that all showed low competency before the program. ‘Understanding of garden culture’ was 15th lowest before the program but showed the biggest increase, ‘development of master gardener course’ was the lowest but showed the second-biggest increase, and ‘garden construction’ was 18th but increased to 3rd after the program. ‘manufacturing of textbooks and tools’ was 19th but showed the 4th biggest increase. Therefore, core competencies that were ranked low before the program generally showed a big increase, thereby showing great education effect.

Table 6 shows the result of analyzing the budget used in the curriculum and the trainees’ willingness to pay according to contingent valuation. The measurement with 73 respondents who participated in the program and 82 respondents working in Agricultural Technology Center who did not participate in the program showed that the coefficient of the participants was 1.771, and the p-value was .002. This was statistically significant, and the participants’ WTP was higher than that of non-participants.

The budget used in this program was total KRW 22.943 million in five items: lecturer fee, facility rental and maintenance fee, material cost, course operation fee, and other costs (Table 7).

Comparison of the curriculum budget with the willingness to pay in the master gardener coordinator education

The WTP by the participants was KRW 33,223 per hour, which exceeds the WTP (KRW 30,000) in the survey, indicating that the trainees think the program is worth more than they pay. Compared to the budget used in the program, 33 hours of education (KRW 33,223 per hour) add up to KRW 1.096 million, which, when multiplied by 73 participants, is approximately KRW 80.008 million. This is also higher than the budget used (KRW 22.943 million), indicating that the value of this program perceived by the trainees is high.

Conclusion

Experts related to nature, plants and gardens can be classified into horticultural therapists (Kim, 2010) and forest therapists for medical and therapeutic purposes, forest interpreters and natural environment educators for interpretation and educational purposes, and urban agriculture managers for hobby and experience purposes.

This study was conducted to perform the role of coordinator to develop rural extension workers into master gardeners. The participants were limited to those with at least a certain level of expertise with regard to master gardener coordinator. As a result of analyzing the performance of each competency to perform the role of a new job as master gardener coordinator, the current performance level was lower than the future demand level in all cases, thereby raising the need for education.

We set 20 competencies for organizational education, learning by experience (work), and individual education as core competencies with high importance and need, and organized 33 hours of 17 master gardener coordinator courses.

The result of performance assessment on the curriculum after the developed program showed that the overall satisfaction was 4.29, and 97.1% of the trainees decided that the program would help them perform their duties. As for change in core competencies after the program, the survey on trainees before and after education showed that all 20 core competencies increased after the program.

As a result of conducting contingent valuation to determine the value of the program, WTP per hour was KRW 33,223 and the total WTP of trainees was KRW 1.096 million, which, when multiplied by 73 participants, is approximately KRW 80.008 million. This is relatively higher than the budget used (KRW 22.943 million), indicating that the program is worth it.

The assessment method showed the possibility that it can be applied to the curriculum provided by Agricultural Technology Center that has issues in effectiveness measurement and assessment, and we provided a reference standard for tuition for the private sector to open a master gardener coordinator curriculum in the future. It is necessary to verify the program for non-public servants currently serving as a master gardener to serve as a coordinator. Further research is needed on separate education programs and competencies focused on non-public servants to train and nurture them into master gardener coordinators.