Strategies for Acceleration of Damaged Area Restoration Project in the Development Restriction Zone

Article information

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to derive institutional improvement methods for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project in greenbelts. The current status of greenbelts in Gyeonggi-do, where greenbelts are extensively distributed was analyzed, and the relevant laws and regulations were reviewed to suggest measures to promote the restoration project. The area of damaged areas within greenbelts in Gyeonggi-do was 6,121,024 m2, accounting for about 0.52% of the total area of greenbelts, and more than 80% was found to be located in Namyangju (55.49%), Hanam (16.48%), and Siheung (8.68%). Various measures to improve the policy were examined as follows: reducing the minimum size of the restoration project area; adjusting baseline of recognizing range of damaged areas; introducing the right of claim for land sale; allowing long-term unexecuted urban parks to be replaced as alternative sites for parks and green spaces; simplifying administrative procedures; and allowing public participation. All of them are expected to promote the restoration project within greenbelts. In results, when the minimum size of area for the restoration project was reduced from 10,000 m2 into 5,000 m2, 3,000 m2 and 2,000 m2, the ratio of the number of combinable lots to the total number of lots increased from 4.4% to 18.8%, 38.8%, and 55.9% respectively in Namyangju. Morever, when the recognizable ranges of the restoration project were extended to the structures obtaining building permit as of March 30, 2016 and obtaining use approvals before December, 2017, the number of applicable lots increased by 5.1% and 9.2% respectively.

Introduction

Korea’s greenbelt policy, formally defined as development restriction zone, was first introduced in 1971 for the purpose of preventing the unplanned spread of cities in the early stage of urbanization, conserving surrounding natural environments, and securing healthy living environments for urban residents (Chang, 1998). Greenbelts have played an important role in securing green spaces, preventing urban sprawl, and creating pleasant living environments. Despite these positive functions, there has been a discussion on the infringement of the property rights of residents who started to live there long before greenbelts were designated, and the presidential election in 1997 and the Constitutional Court’s decision of constitutional unconformity in 1998 resulted in improvement in the policy (Kwon et al., 2013). In 2000, the Act on Special Measures for Designation and Management of Development Restriction Zones (hereinafter the Act of Development Restriction Zones) was enacted, and development restrictions on the entire greenbelts in seven small and medium-sized cities, and the part of the greenbelts in seven large-sized cities were lifted. Since then, regulations have been continuously eased for improving living convenience by, for example, permitting some facilities and uses prospectively (Kwon et al., 2006; Lee and Jeong, 2019; Park and Kim, 2009). However, the number of cases of abusing the eased regulations, for example, obtaining authorization and permission as legal facilities and later changing their use into factories or warehouses or extending them illegally have been increased (Jung, 2011). To prevent the occurrence of these illegal acts and strengthen the control of greenbelts, various institutional attempts have been made such as introducing the enforcement fine policy in 2009 (Chae et al., 2015).

Damaged areas in greenbelts are the lands that were originally legally authorized and permitted as a facility related to animals or plants but were used as warehouses, factories or workshops after changing their use, which can be attributed to the fact that the profits from leasing or utilizing illegal structures are higher than the enforcement fine imposed due to illegal acts (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). The results of a survey conducted on public servants in local governments in 2013 show that residents or land owners seem to develop lands within greenbelts for profits knowing that it is an illegal act (Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs, 2013). The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport temporarily introduced the Damaged Area Restoration Project to encourage residents themselves to improve facilities like illegally used warehouses. The Damaged Area Restoration Project was designed to systematically reduce illegal facilities in damaged areas within greenbelts, to secure lands for urban parks and green spaces and thus to improve urban environments. The purposes of the project are to improve damaged areas and to enhance public interests by authorizing the illegally used facilities when repairing the damaged area and making and donating a portion of the sites as infrastructure such as urban parks and green spaces, and roads are being constructed (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, 2016).

The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport made various efforts in 2016 such as releasing guidelines for the Damaged Area Restoration Project, and holding a public hearing. Since the project had shown no performance, the Act of Development Restriction Zones was amended in December, 2017 to extend the project period to 2020 for 3 years. However, various difficulties in carrying out the project, including residents’ low awareness of the project, a low budget, and issues associated with regularized forming damaged sites and determining the optimal area of a project site have been continuously pointed out by project participants (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). To promote the Damaged Area Restoration Project, the act was amended in August, 2019 to lay a foundation for the smooth execution of the project by including some part of the roads within a target site into the area of urban parks and green spaces that have to be donated, and permitting the alteration of the shape and quality of lands caused by constructing or installing existing structures. Its enforcement decree and guidelines are also being amended currently.

This study was conducted to suggest measures to improve the policy for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project and to reflect them in the policy. The earlier results of this study have been already reflected in the amended Act of the Development Restriction Zones, and will be additionally reflected in the on-going process of amending the enforcement decree. Here, key ideas in the measures to promote the Damaged Area Restoration Project obtained in the study were summarized.

Research Methods

This study aimed to analyze the status of damaged areas within development restriction zones (greenbelts), and suggest measures to improve the policy for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project. The project was designed and has been executed to improve damaged areas that have been extensively observed in Gyeonggi-do. Against this backdrop, the spatial scope of this study for analyzing the status of damaged areas within greenbelts was set as Gyeonggi-do that has the largest area of greenbelts in Korea, and the temporal scope was set as 2017 considering the collectability of statistical data.

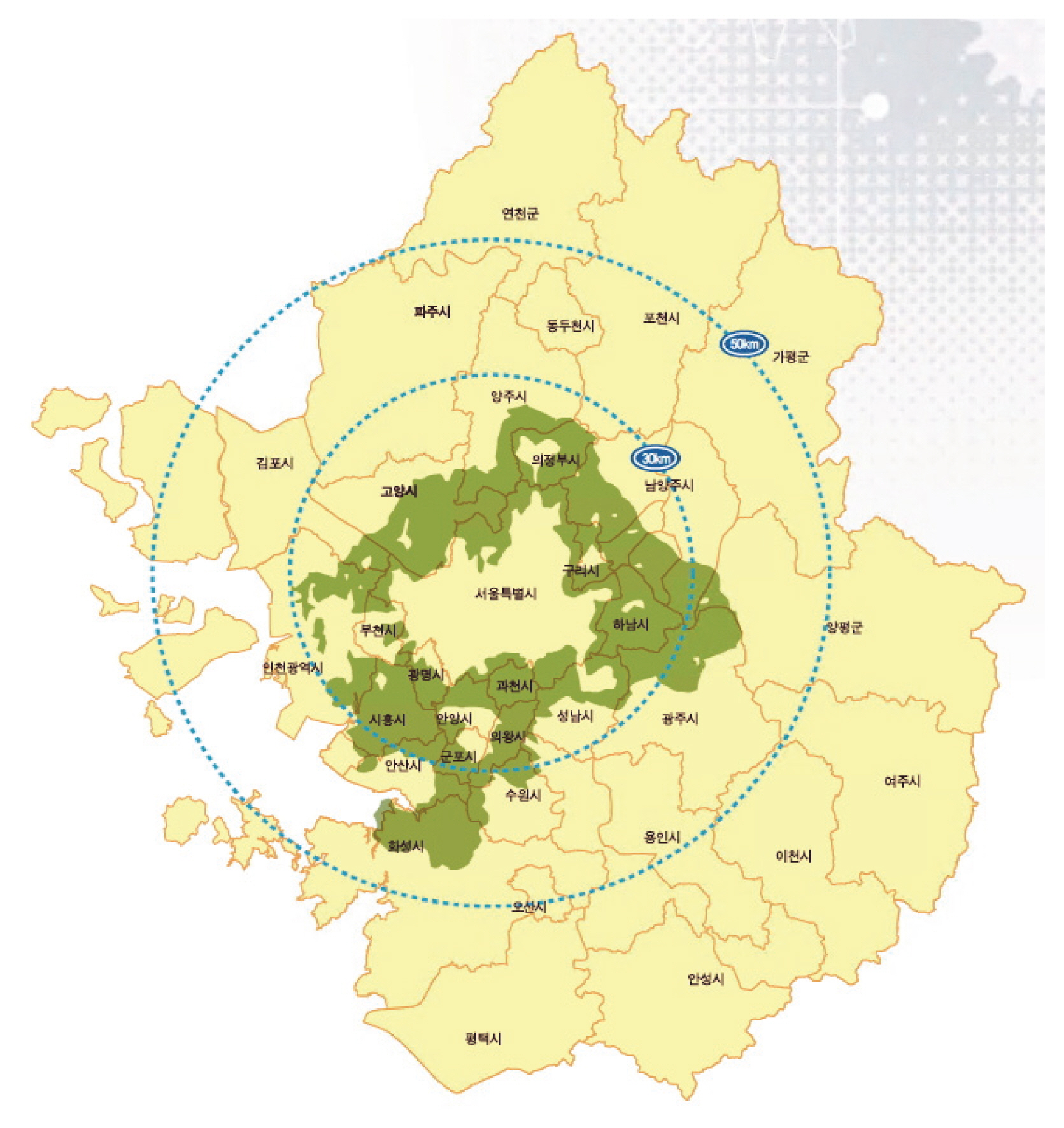

Gyeonggi-do is composed of 31 cities and counties, and 21 cities have greenbelts (Fig. 1). As Gyeonggi-do surrounds Seoul, its population density and development pressure are high, which results in damaged areas that are extensively distributed within greenbelts. The number of households and population in Gyeonggi-do has continuously increased to 5,131,379 households and 13,255,523 persons in 2017 (Gyeonggi Statistics, 2019). Statistical data available in Gyeonggi were used to analyze the area of administrative districts and greenbelts and the distribution of land categories in each 21 cities and counties where greenbelts were designated, and data on the distribution of damaged areas and the status of land categories were collected from individual cities and counties.

To establish measures to improve the policy that can maintain its original purpose but still promote the Damaged Area Restoration Project, this study reviewed relevant laws including the National Land Planning and Utilization Act (hereinafter the National Land Planning Act), the Act of Development Restriction Zones and the Urban Development Act, and other various policy documents including the Guidelines for Executing the Damaged Area Restoration Project (Korea Ministry of Government Legislation, 2019; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, 2016). Based on the results of the review, discussions with researchers and consultations with experts were conducted to establish measures to adjust the minimum area of the project, and the baseline for recognizing range of damaged areas; measures to introduce new policies such as permitting the right of claim for land sale or utilizing long-term unexecuted urban parks as alternative sites; and measures to simplify administrative procedures for the project and to expand project participants into the public sector. To observe the effects of adjusting the minimum area and the baseline for recognizing damaged areas on the promotion of the project, changes in the area of target sites when the adjustment was performed on Namyangju and the entire Gyeonggi-do respectively were analyzed. To analyze the number of lots that can be grouped to satisfy the minimum area, data on the status of greenbelts and a geographic information system (GIS) that integrated geographic data were utilized. The Electronic Architectural Information System (www.eais.go.kr) operated by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport was used to analyze the lots that satisfied the conditions for the project by city and county after adjusting the baseline for recognizing damaged areas.

Results and Discussion

Analysis of the status of greenbelts and damaged areas in Gyeonggi-do

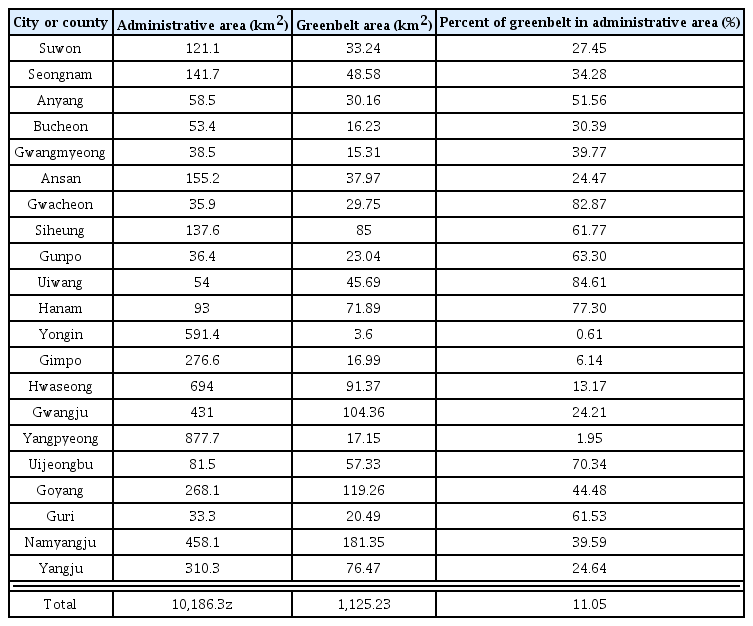

The area of administrative districts and greenbelts in 21 cities and counties in Gyeonggi-do where greenbelts were designated as of 2017 was shown in Table 1. The total area of greenbelts was 1,125.23 km2, approximately 11% of the total area of administrative districts (10,186.3 km2). By city and county, the area in Namyangju was the highest (181.35 km2), followed by Goyang (119.26 km2), Gwangju (104.36 km2), and Hwaseong (91.37 km2), and that in Yongin was the lowest (3.6 km2). The ratio of the area of greenbelts to the area of administrative district by city and county in Uiwang was the highest (84.61%), followed by Gwacheon (82.87%), Hanam (77.30%), and Uijeongbu (70.34%). Although Namyangju ranked in the middle in terms of the ratio (39.59%), the absolute area of greenbelts was the highest, which has made it to be one of the major targets of research related to greenbelts (Chae et al., 2015; Park, 2009; Park and Kim, 2009). In terms of the area of land categories, that of forests was 682.97 km2, accounting for about 60.7% of the total area of greenbelts, followed by others (214.16 km2), paddies (108.68 km2), and fields (108.52 km2; Fig. 2).

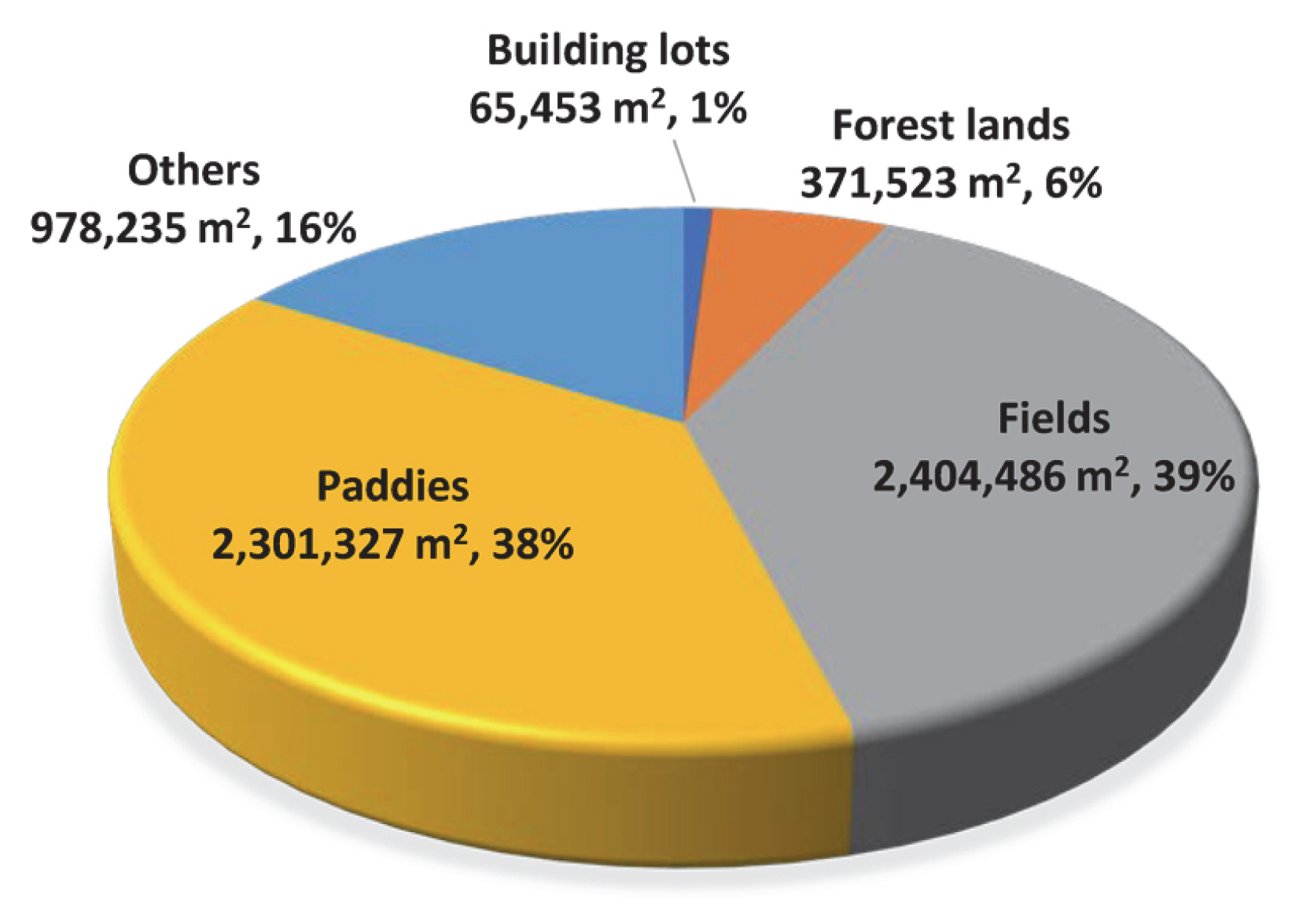

‘Damaged areas’ in the Damaged Area Restoration Project mean lands where damaged facilities account for over 20/100 of the area of lands, and ‘damaged facilities’ mean facilities related to animals and plants that were installed before March 30, 2016 such as pens (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, 2016). The status of damaged areas within the greenbelts in Gyeonggi-do is as shown in Table 2. The area of damaged areas that utilized farmlands as open storage or warehouse without any permission from the authorities was 6,121,024 m2, accounting for about 0.52% of the total area of greenbelts. By city and county, Namyangju was found to have the largest area of damaged areas (3,396,642 m2), followed by Hanam (1,008,737 m2), Siheung (531,003 m2), and Yangju (247,805 m2). In terms of the ratio of the area, Namyangju showed the highest ratio (55.49%), followed by Hanam (16.48%), Siheung (8.68%), and Yangju (4.05%). In terms of the number of lots, that in Namyangju was the highest (3,033), accounting for 60.41%, followed by Hanam (689 lots, 13.72%), Goyang (279 lots, 5.56%), and Siheung (243 lots, 4.84%). In terms of the area of damaged areas within greenbelts, the top 3 cities including Namyangju, Hanam and Siheung accounted for over 80%, and specifically Namyangju accounted for over 55% of the total area of damaged areas, and 60% of the total number of lots. The status of land categories by city and county was as shown in Fig. 3. The area of fields was 2,404,486 m2, accounting for 39.28%, followed by paddies (2,301,327 m2, 37.60%), and others (978,235 m2, 15.98%), and fields and paddies were found to account for about 77% of the total area of damaged areas.

Measures to improve policy for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project

Relaxation of the criteria for the minimum size of the Damaged Area Restoration Project

The Damaged Area Restoration Project for greenbelts was introduced by applying the replotting method in the Urban Development Act, and the unit area of a natural green area (over 10,000 m2), one of the designated conditions for urban development zones, was set as the minimum size of the project. Some residents and local governments, however, have called for the relaxation of the criteria since it is difficult to form a target site that meets the minimum size while obtaining 100% consent of land owners.

The Damaged Area Restoration Project was designed to systematically reduce unplanned, damaged facilities within greenbelts, to secure urban parks and green spaces for restoring the function of green spaces, and thus to improve urban environments. It seems to be reasonable to maintain the minimum area of a project site (over 10,000 m2) in order to systematically improve damaged areas by applying the procedures for urban development projects in the Urban Development Act, and reflecting them in planning the management of greenbelts. If the minimum area is lowered to smaller than 10,000 m2, it is necessary to add a new clause for exception to the rule for designating urban development zones, which requires the amendment of the Urban Development Act and more grounds for installing parks and green spaces (land donation) in the Act on Urban Parks, Green Areas, etc. (Korea Ministry of Government Legislation, 2019). In addition, the effect of improving damaged areas on a small scale is not significant, and it is also difficult to systematically improve damaged areas. Nevertheless, it can be considered to allow to combine small- and medium-scale sites for the restoration project while maintaining the minimum area for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project. Currently, the Damaged Area Restoration Project allows to combine ‘close damaged areas’ and ‘scattered damaged areas,’ for instance, when the area of close damaged areas accounts for over 70% of the total project area, they are allowed to be combined with scattered damaged areas (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, 2016). The number of lots that can be grouped to meet the minimum area (over 10,000 m2) in Namyangju when small-scale areas are combined is as shown in Table 3. A total of 2,841 lots of damaged areas were analyzed, and 70% was applied to the area of damaged areas that can be grouped for the project. For instance, when designating the land of 3,000 m2 as a project target, the land can be composed of 2,100 m2 (70%) damaged areas and 900 m2 (30%) non-damaged areas, and the number of groups utilized in the restoration project was found to be 460, and the number of lots, 1,101. When the current minimum area, 10,000 m2, is applied, the number of lots that can be designated as a target site is 124, accounting for only 4.4% of the total number of lots. However, when the minimum area is 5,000 m2, the percentage increases to 18.8%. When combining small-scale areas sized over 3,000 m2 to meet the minimum area (over 10,000 m2), 38.8% of the total damaged areas in terms of the number of lots can be designated as a target site. When the minimum area is 2,000 m2, the percentage of lots that can be grouped increases to 56%. These results indicate that it is possible to promote the project by grouping small- and medium-scale areas while maintaining the total area of the project. Still, when the minimum area of damaged areas is lowered excessively, the effect of the restoration project can be reduced, resulting in the increasing number of unplanned development areas. Therefore, to satisfy the original purpose of the project, it is necessary to promote the Damaged Area Restoration Project, and at the same time to identify and apply the optimal scale for the project.

Adjustment of time for determining damaged areas

Damaged areas are recognized based on the time when the Enforcement Decree of the Act of Development Restriction Zones was amended. That is, structures that were installed and recorded on the building register before March 30, 2016 are subject to the Damaged Area Restoration Project. Considering the purpose of the project, when the project targets all the illegally misused structures, it can result in a confusion in law and order and problems associated with fairness (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). However, the current conditions, such as the very low performance of the restoration project, and the temporary introduction of the system, need to be considered. Considering them, it is necessary to review measures to prevent illegal acts in advance and expand the effect of the restoration project by targeting also those that were under construction or began construction after legally obtaining building permits before the enforcement decree was enacted. Table 4 shows the comparison of the number of lots by city and county that can be recognized as damaged areas when target sites are expanded under different baselines for recognizing damaged areas: those of which building permits or use approvals were issued by March 30, 2016, or those of which use approvals were obtained by December 31, 2017 to which the period of the restoration project was extended. When the current baseline was applied, a total of 6,188 lots within the entire greenbelts in Gyeonggi-do were found to meet the conditions of damaged areas, but when those of which building permits were obtained by the enactment date of the enforcement decree were included, the number increased to 6,501 lots, up by about 5.1%. When the baseline was extended to December, 2017, the number increased to 6,759 lots, up by about 9.2%. In the case of Namyangju and Hanam where many damaged facilities were installed, the percentage was found to be increased by adjusting the baseline by 4.5–10.5% and 3.6–6.0% respectively. As such, it is possible to promote the project by increasing the number of target sites through the adjustment of the baseline for recognizing damaged areas.

Introduction of the right of claim for land sale

Earlier applications for the Damaged Area Restoration Project show that some land owners dropped out in the middle of the project after submitting their application form. As this resulted in failure in forming a target site that meets the conditions of the project, they were rejected. Under the current regulations, every land owner within a target site needs to sign a consent form in order to execute the project. Therefore, when there is any land owner who does not consent to the project, there is no other way to push ahead the project, which makes it difficult to form a target site sized over 10,000 m2 (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). To relax the criteria for the area of target sites, it is necessary to amend the enforcement decree of the relevant law, but since the consent of land owners for the restoration project is subject to the regulations on performance, it is possible to improve the policy simply by amending the regulations on the consent of land owners for the restoration project. The Act on the Improvement of Urban Areas and Residential Environments amended in February, 2017 also has an applicable provision on the right of claim for land sale for the smooth execution of reconstruction projects. Since residents and local governments complain that it is difficult to meet the minimum size of a target site (10,000 m2) by obtaining 100% consent from land owners for the Damaged Area Restoration Project, the project can be smoothly executed by lowering the percentage of the consent of land owners for the approval of the restoration project, and allowing land owners who do not consent to the project to exercise their right of claim for land sale even after the project is approved (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). Still, in this case, non-damaged areas surrounded by damaged areas are subject to the right of claim for land sale, which can cause disadvantages to the land owners who abide by the law. Therefore, this problem can be prevented by limiting the right of claim for land sale to damaged areas.

Utilization of long-term unexecuted parks as alternative sites

If long-term unexecuted parks are recognized as alternative sites for parks and green spaces that need to be donated under the Damaged Area Restoration Project, various positive effects can be induced. Long-tern unexecuted parks were originally designed as an urban planning facility for improving urban residents’ quality of life, but their execution has long been delayed due to the financial conditions of local governments, being left as unexecuted urban planning facilities. As of December, 2017, the total area of long-term unexecuted urban parks in Gyeonggi-do was 67,193,634 m2, and the cost of execution is estimated to be about 7.26 trillion won (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. 2018). When creating parks and green spaces with some part of the sites for the Damaged Area Restoration Project, an additional cost, along with the cost for creating parks, can be created for tearing down the existing structures, and other problems can be caused such as creating parks in areas where the utilization rate of parks is not high. When lifting development restrictions and executing public housing projects, long-term unexecuted parks are recognized as a target site for restoring damaged areas, and thus it can be considered to apply this to the Damaged Area Restoration Project in order to install parks in target sites, and to use long-term unexecuted parks in the same city or county as alternative sites instead of land donation (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). That is, when creating alternative parks in long-term unexecuted parks under the restoration project, the area of target sites and the area of the long-term unexecuted parks used as alternative sites can be combined. In other words, the minimum area 10,000 m2 can be met by alternatively creating parks and green spaces in 7,000 m2 sites for the Damaged Area Restoration Project and 3,000 m2 long-term unexecuted parks, and residents can push ahead the project with 7,000 m2 damaged areas. This method can reduce local governments’ financial burden, create parks and green spaces in desired locations, expand the effectiveness of the Damaged Area Restoration Project within target sites. In addition, it is possible to practically relax the criteria for the area of target sites and at the same time meet the minimum area of target sites under the Urban Development Act, which is a feasible way with the minimum amendment of laws. It is expected to promote the restoration project and increase the execution rate of long-term unexecuted parks by utilizing long-term unexecuted parks as alternative sites for the project.

Simplification of procedures and expansion of project participants

The Damaged Area Restoration Project is simply for changing the purpose of use, but the procedures are very complicated, and consume a significant amount of time, which makes it difficult to execute the project. The procedures for executing the restoration project differ depending on the type of project participants such as land owners and associations, and on average 36 months are required. For projects that are temporarily introduced like the Damaged Area Restoration Project, their procedures need to be simplified in order to improve the effectiveness of the policy. Currently, the restoration project is executed through the following process. First, land owners or associations form a target site for the restoration project. After establishing plans, plans for managing development restriction zones are revised and approved. When revising the plans, local urban planning committees and the central urban planning committee deliberate on the revised plans in order. When authorizing and permitting the restoration project, local urban planning committees also go through the deliberation process, consuming a significant amount of time only for deliberation, In addition, in the processes of changing the plans for managing greenbelts and authorizing and permitting urban development projects, procedures such as public hearings, consultation between relevant organizations and deliberation of local urban planning committees are repeated, consuming an excessive amount of time. Various methods of simplifying procedures can be considered, but it is necessary to find the method that avoids the amendment of laws that consumes a significant amount of time and complicated procedures as much as possible, but can promote the restoration project. In this regard, it can be considered to change the plans for managing greenbelts and authorizing and permitting urban development projects at the same time. This method seems to be a practical way to reduce the period of execution, to skip the process of establishing plans for greenbelts and thus to improve the effectiveness of the policy.

When executing projects using a replotting method like the current restoration project, projects can be often suspended due to the bankruptcy of land owners or the dissolution of associations. The period of the project also can be extended and various types of problems such as money problems can be caused as entities who do not have enough expertise in replotting lead the project. By engaging local governments, public organizations or publicly-owned companies as a project entity, several advantages can be secured to some extent such as executing the restoration project in a planned way, securing public facilities, developing income sources for land owners who do not have enough resources, and expanding parks, green spaces and leisure facilities. However, permitting the public sector to lead the project without any restriction can discolor the original purpose of the policy as a private sector-led public contribution. The project can be promoted by allowing it to be led by public sector but requiring the participation of land owners. That is, since the Damaged Area Restoration Project requires the replotting method, the Urban Development Act can be applied, and thus public organizations can be designated as a project entity when half of the total area of a target site and half of the owners of a target site agree (Korea Land and Housing Corporation, 2019). As the Damaged Area Restoration Project was introduced to ensure residents restore and resettle damaged areas by themselves, it is unable to adopt the full acceptance method, and it is also difficult to take full advantage of public sector-led operation. However, by engaging public organizations as a project entity, the project can be carried out only with the consent of half of land owners, not all of them, which makes it easy to form a target site. If the project is led by the public sector, the public sector can survey and select damaged areas that need to be improved, and establish and propose project plans to residents, encouraging land owners to participate in the project. In addition, when a circular development approach is adopted under the Urban Development Act, several sites can be grouped together as one restoration project, and be developed in a circular way, and by doing so the anxiety that residents may experience due to the loss of income sources caused by the demolition of existing structures can be reduced and their participation in the project can be induced. These measures to improve the policy for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project were summarized in Table 5.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the status of damaged areas within development restriction zones (greenbelts) in Gyeonggi-do, and reviewed the following measures to improve the policy for promoting the Damaged Area Restoration Project: reducing the minimum area of a target site for the project; adjusting the baseline for recognizing damaged areas; introducing the right of claim for land sale; utilizing long-term unexecuted parks as an alternative site; and simplifying administrative procedures and allowing public participation. The total area of damaged areas within greenbelts in Gyeonggi-do was 6,121,024 m2, accounting for about 0.52% of the total area of greenbelts. The ratio of the area in Namyangju was the highest (55.49%), followed by Hanam (16.48%) and Siheung (8.68%), and the top 3 cities accounted for over 80% of the total area of damaged areas in Gyeonggi-do. When the minimum area of a target site for the Damaged Area Restoration Project was maintained at the current level (10,000 m2), the number of applicable lots in Namyangju was found to account for 4.4% of the total number of lots within greenbelts in Namyangju, but when the minimum area was lowered to 5,000 m2, 3,000 m2, and 2,000 m2, the percentage increased to 18.8%, 38.8% and 55.9% respectively. When structures that obtained building permits before March 30, 2016 - the current baseline for recognizing the damaged areas - or obtained use approvals before December 31, 2017, to which the period of the restoration project was extended, were recognized as target sites, the number of applicable lots in Gyeonggi-do increased by 5.1% and 9.2% respectively, and that in Namyangju was found to increase by 4.5% and 10.5% respectively. By introducing the right of claim for land sale, the consent ratio of land owners for applying for the restoration project can be reduced, which makes it easy to meet the conditions for forming a target site and thus promotes the restoration project. Utilizing long-term unexecuted parks as alternative sites can prevent a decrease in urban residents’ quality of life caused by the lapsing of long-term unexecuted parks, and induce the promotion of the Damaged Area Restoration Project. At the same time, the effectiveness of the policy needs to be expanded by simplifying administrative procedures and engaging public organizations as a project entity.

Notes

This paper is the result of analyzing and arranging the report of ‘A study on the development plan of the damaged area restoration project in Greenbelt’ accomplished by Korea Land and Housing Corporation with the support of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport.