Comparative Analysis of Gender Differences in Satisfaction with School Wall Removal and Greening - A Case Study of an Elementary School in Daegu Metropolitan City

Article information

Abstract

To examine the gender differences in satisfaction of elementary school students with school wall removal and greening, a survey was carried out targeting 168 sixth grade students (92 boys and 76 girls) of an elementary school in Daegu Metropolitan City, Korea. As a result, the students were generally satisfied with wall removing and greening, and gave their higher marks in school’s image promotion (4.24), school landscape improvements (4.21), and expanding green space (4.06) on a 5 point scale. They also showed a little positive responses to increments of gardening opportunities (3.41) and talks with their friends (3.19). Whereas, they were somewhat more aware of strangers (3.35) and concerned about the probability of crime occurrence (3.36) after removing the school walls. There was no significant difference between male and female students in general satisfaction with wall removal and greening. Meanwhile, schoolgirls gave significantly higher scores regarding school’s image promotion and awareness of strangers than schoolboys (p〈 .001). More female students also acknowledged changes on school landscape improvements and increases in talks with their friends, and are more concerned about crime occurrence than male students (p〈 .05). Therefore, it is needed to pursue further study to maximize the positive effects and minimize the negative ones of school wall removal. In addition, the school projects should be designed to ensure the safety and security of all students in the school environment.

Introduction

A wall, which is the vertical element among various elements that form an urban environment, surrounds a certain building or site to protect it or set up a boundary. In other words, walls surround individual space to indicate the boundaries of ownership to limit the exterior space of a building, while also serving as a defensive measure to protect the objects or people within the surrounded space from natural disasters, fierce animals or outside invasions. These walls both separate and connect two spaces at the same time, thereby securing territoriality of space overall (Baek et al., 2010).

Walls have played their own roles and functions this way by maintaining the identity of individual space in human history. However, with the intensifying individualism along with social development and the weakening connectivity among human beings at this point, walls in the modern cities of Korea are making the urban spaces in which we live more closed and exclusive, further increasing communication breakdowns among people and making the lives more cold-hearted (Chung, 2002).

However, recently there are increasing demands for the pleasant environment of urban dwellers along with the increased standard of living, with the society seeking various implementation strategies to recover the community (Kang, 1993). Accordingly, the society seeks expansion of green space that was not easily accessible in daily life and formation of an open community by removing the walls of public institutions or schools that are emerging as the obstacle to beautiful urban landscape and aesthetics (Shim, 1984). School walls made of concrete or iron structures that mostly suggest constraint or defensiveness are torn down and green spaces are formed instead, thereby providing citizens with a place to meet and relax and students with a new venue for learning (Lee, 2008; Lim and Jeong, 2007). Furthermore, removing walls, connecting the interior and exterior space of individual areas and greening them not only indicates opening a closed space but also implies opening the closed hearts of people for various encounters (Jeong, 2000).

However, destroying the school walls does not only have positive effects. Rather, it is more desirable to keep the walls for overall landscape, a certain unique mood or crime prevention, which is why walls shall not be removed altogether. With this issue in mind, this study intends to evaluate and analyze the effects and satisfaction of openness due to the wall removal of an elementary school in the perspective of students, thereby providing basic knowledge necessary in setting the desirable direction for wall removal in the future.

Research Method

Subjects

A survey was conducted on 168 sixth grade students in S Elementary School located in Daegu, which carried out a greening project after removing school walls. Figure 1 shows the pictures of school that carried out the greening project after removing the school walls to measure the satisfaction with school wall removal and greening. Trees were planted around the parts where the walls were removed, and aquatic plants were planted at the center with a pond, with sporting equipment installed around the schoolyard.

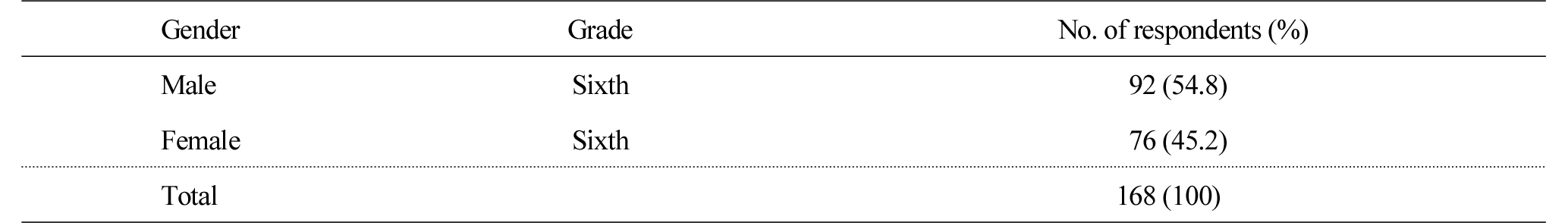

As for the gender ratio of the subjects, there were 92 male students (54.8%) out of total 168 students, and 76 female students (45.2%) (Table 1).

Method

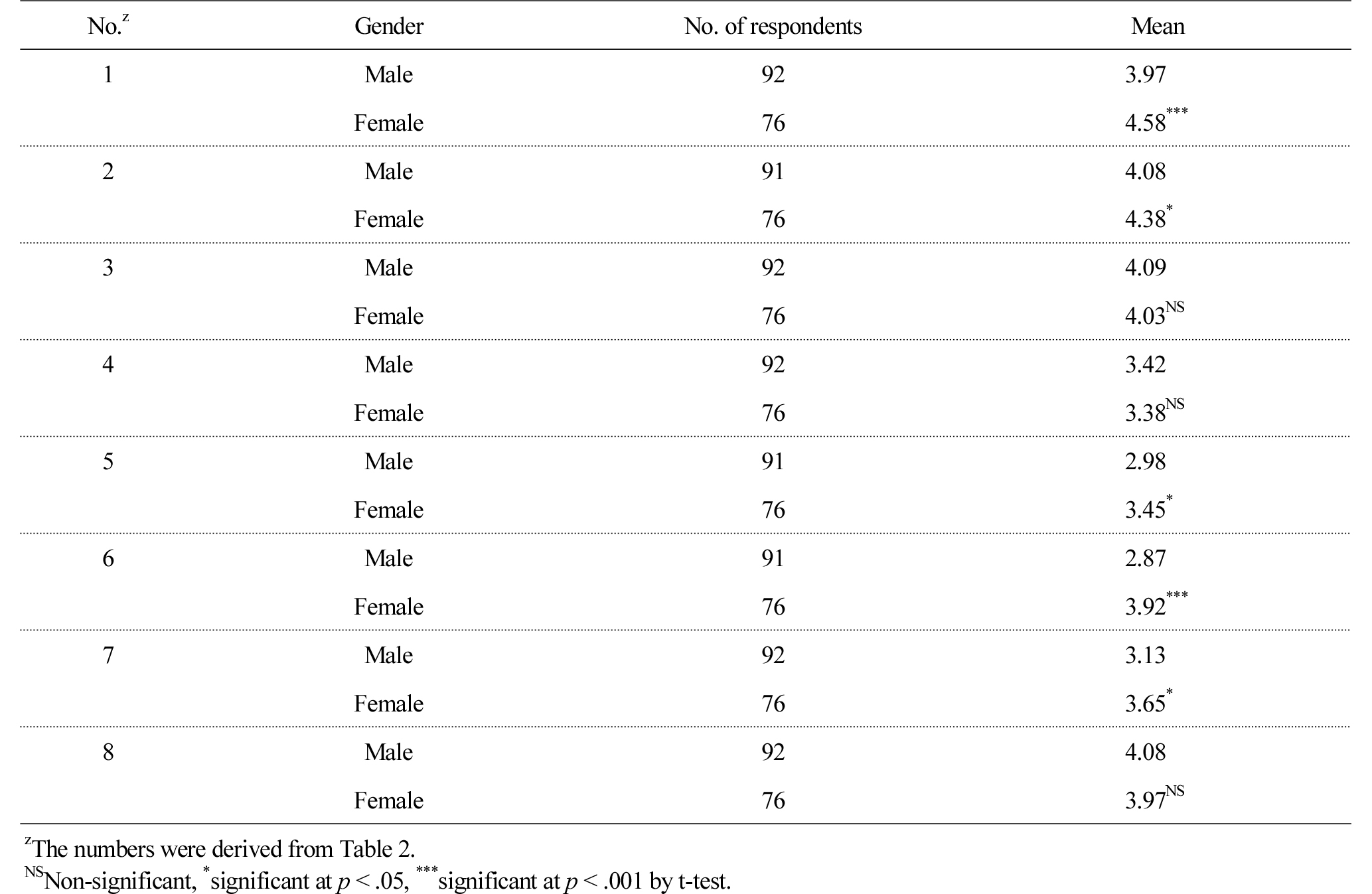

A survey was conducted to determine the effects of creating green space by removing walls from an elementary school on the satisfaction of students. The questionnaire consisted of 8 items as shown in Table 2, which were rated on a 5-point scale. The survey was conducted for 30 days from April 1 to April 30, 2009. The results were compared between male and female students through a t-test.

Results and Discussions

Satisfaction of students with wall removal and greening of the elementary school

As a result of analyzing the perception on school wall removal with a survey of 8 items (Table 2) among 168 male and female students in the 6th grade of an elementary school, it was found that the students were generally satisfied. The result of each item can be analyzed as follows.

Regarding whether the school’s image improved after removing the school walls (No. 1), students gave a high score of 4.24 (out of 5). They also gave a high score of 4.21 to the question of whether the school looks more beautiful compared to before removing the walls (No. 2). The score was also high at 4.06 to the question of whether there is more green space such as flowering plants or trees after removing the walls (No. 3). These three items show positive changes that appear on the exterior due to the removal of walls, for which students gave positive feedback. The evaluation result for the school park project of 10 elementary schools in Seoul also showed that the school grounds lit up compared to before the project as many flowering trees have been planted, which is a great accomplishment (Lee, 2008). Chung (2002) also stated that there is a positive aspect in removing walls, such as increase of green spaces and improvement of urban landscape.

However, the students gave relatively low scores to the question of whether there are more opportunities to tend flowering plants or trees after removing walls (No. 4) (3.41) and the question of whether they have more conversations with friends after removing walls (No. 5) (3.19). It is also important for school wall removal to bring positive changes in terms of emotions and interpersonal relations by changing the learning or leisure activities of students, in addition to merely changing and improving landscape, which is something that is still insufficient.

Furthermore, the students gave relatively lower scores than other items to the question of whether they are more aware of strangers after wall removal (No. 6) (3.35) and the question of whether they think crimes will increase after wall removal (No. 7) (3.36), which were both higher than 3.0 and thus indicates that students feel somewhat anxious about the removal of walls that form the boundaries with the outside. Chung (2002) also pointed out the concern for crimes and invasion of privacy as the negative aspects of wall removal. This is different from the report by Baek et al. (2010) and Kim et al. (2011) that the physical environment that changed after the wall removal project of residential areas has a positive effect on satisfaction with crime prevention. Therefore, it is necessary to plant trees or install structures that conceal the space from the outside depending on the characteristics of the space, and also to reinforce the system that guarantees safety.

Finally, the average score for the question of whether students are satisfied with wall removal (No. 8) was high at 4.03, which showed that the students were satisfied with school wall removal and school greening. However, there still are things to improve such as resolving slight anxiety over the view from the outside and safety, purifying the emotions of students and improving interpersonal relations by implementing horticultural activities or field trips within the changed environment.

Gender differences in satisfaction with school wall removal and greening

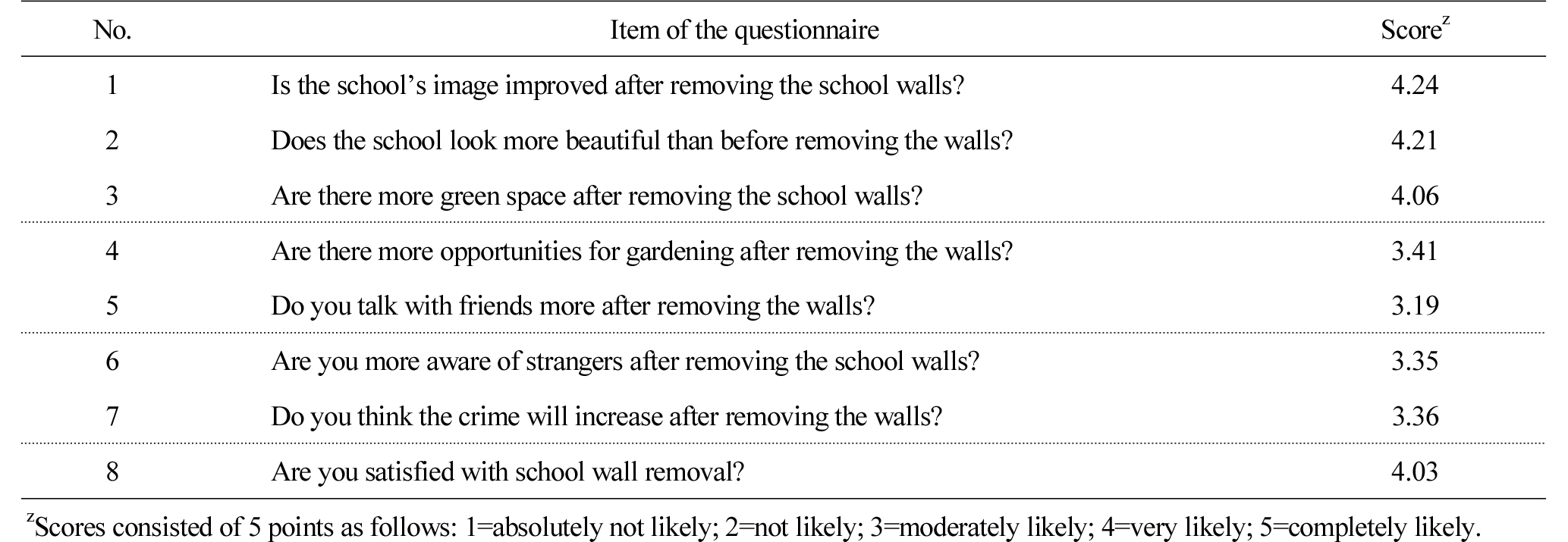

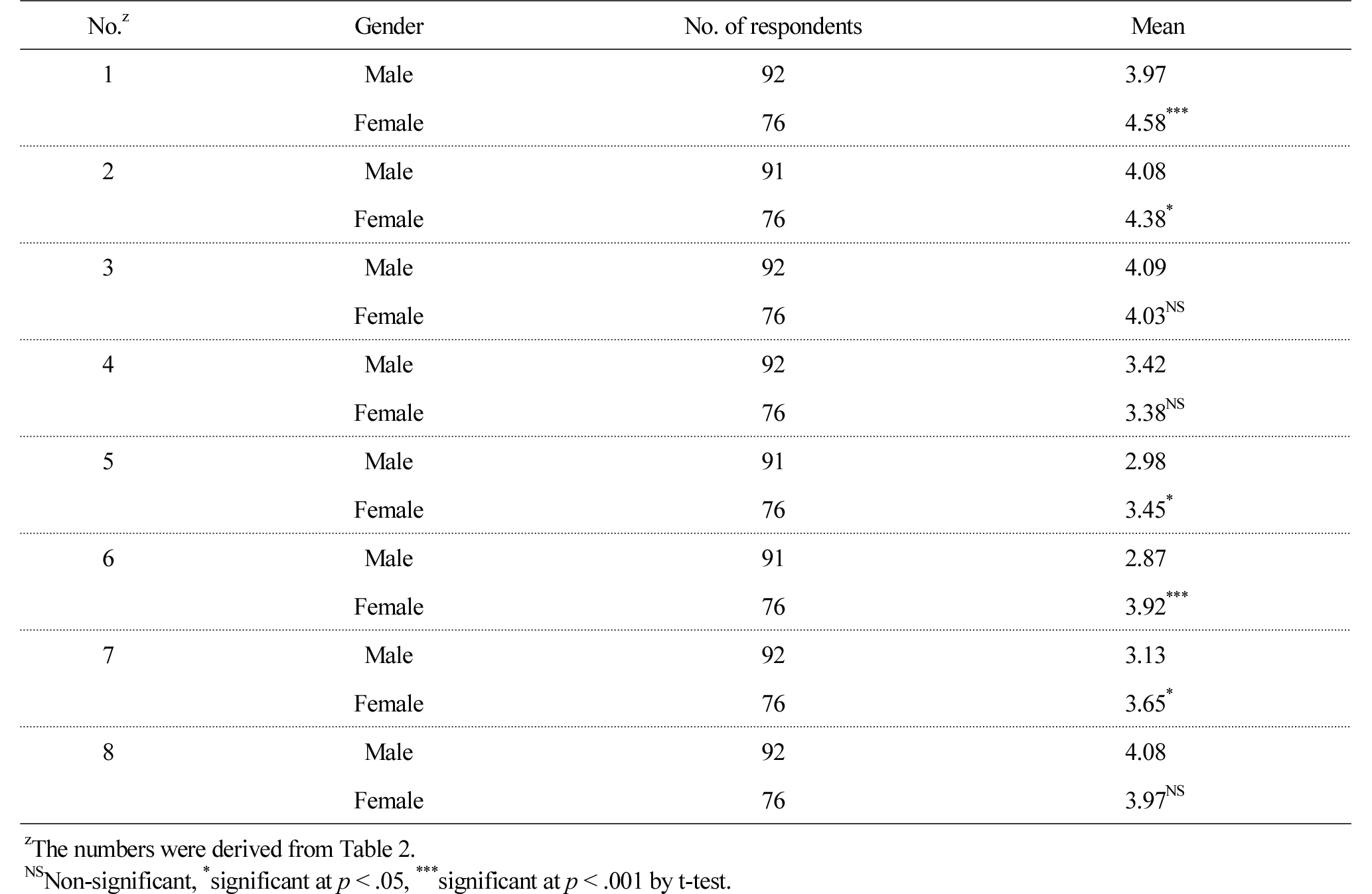

As a result of the t-test on gender differences in school’s image improvement after wall removal (Table 3, No. 1), it was found that there was a high level of significant difference (p〈 .001). In terms of average score, both male and female students felt that the school’s image improved, but there was a huge perception gap regarding the level of improvement between the two groups, with more female (4.58) than male students (3.97) thinking that the school’s image improved. However, there are differences according to school size, characteristics of the school, number of students, surrounding circumstances, and objectives and method of education for each school, and school landscape may vary in terms of content and location depending on regional characteristics serving as a neighborhood park (Park and Choi, 2011).

In terms of improved beauty of the school, more female (4.38) than male students (4.08) thought that the school looks more beautiful after wall removal (p〈 .05) (No. 2). This is similar to the result of the attitude survey of residents (Jeong et al., 2002) thinking that the landscape improved after removing the walls of the government office, which indicates that students prefer favorable physical environment within their living space.

There was no significant gender difference regarding expansion of green space (No. 3). In other words, regardless of gender (male 4.09, female 4.03), the students thought that there is more green space after removing school walls. It turned out that the school characteristics are represented by how the surrounding environment is formed after removing the walls, which is a good case of forming green space through wall removal in an inadequate urban space.

There was no significant gender difference regarding the perception on increased chances for horticultural activities (tending flowering plants or trees) (No. 4). This result indicates that it is necessary to actively use the green space as a venue for environmental education along with the school subjects for students in terms of use of green space after school wall removal. To this end, it is also necessary to apply horticultural activities and horticultural therapy programs, and establish space for such activities such as school forests, vegetable gardens or flower beds.

Regarding the question of whether students talk more with friends after school wall removal, there was a gender difference between male and female students (p〈 .05) (No. 5). Male students (2.98) did not feel much difference in the chance to talk with friends before and after wall removal, but female students (3.45) showed a slight increase. In other words, as there is more green space after wall removal, female students used that space as a venue for interaction with friends, thereby promoting peer relations.

There was a high level of significant gender difference regarding the strangers awareness after removing walls (p〈 .001) (No. 6). Male students (2.87) did not feel much difference about strangers even after removing walls, whereas female students (3.92) were feeling a greater burden about strangers. Since it turned out that female students perceive the school as their private living space, it seems necessary to consider measures to protect their privacy.

There was also a significant gender difference in terms of perception on increased probability in crime occurrence (p〈 .05) (No. 7). More female students (3.65) than male students (3.13) responded that crimes will increase after removing walls. This is similar to the question about strangers, indicating that female students are feeling somewhat more burdened by the removal of school walls than male students. However, the average score for both male and female students was 3.36 in terms of crime occurrence, which was the biggest concern after removing walls, implying that the survey participants (sixth-grade students in elementary school) think that school walls are not the fundamental means to prevent crime occurrence. Choi (2005) also proved that there is little concern for crime occurrence due to closed-circuit televisions (CCTVs) or voluntary crime prevention guards, but in the end, whether there are school walls or not, there must be protective devices or attention for elementary school students.

There was no gender difference for overall satisfaction with school wall removal (No. 8). The average satisfaction by gender was 4.08 for male and 3.97 for female students, indicating that both male and female students were satisfied with school wall removal. It was noted that female students, who showed higher satisfaction with wall removal than male students in Items 1-5, gave relatively low score in overall satisfaction, which may be related to the awareness of strangers and possibility of crime occurrence in Items 6-7. In other words, female students responded more sensitively than male students to both positive and negative aspects of wall removal.

Regression analysis for satisfaction with school wall removal and greening

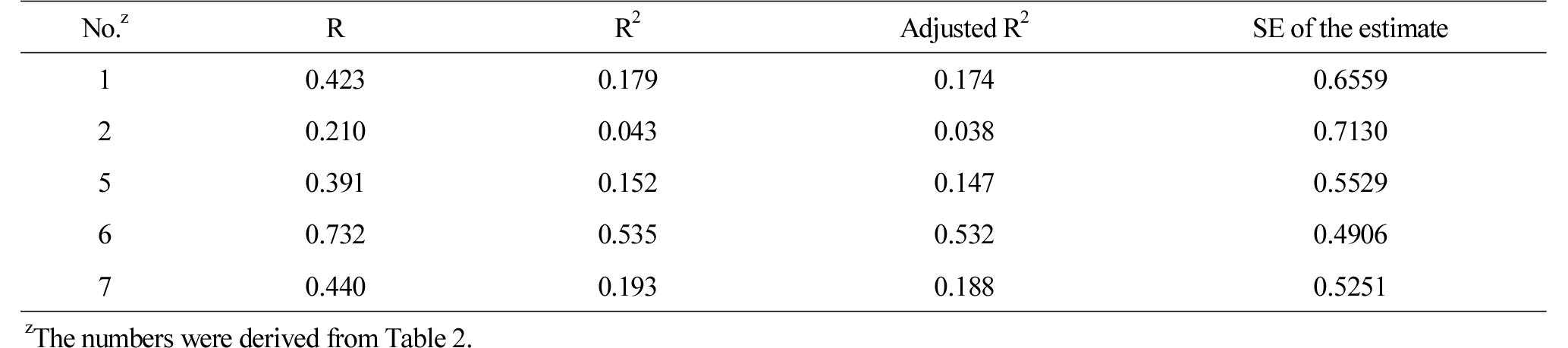

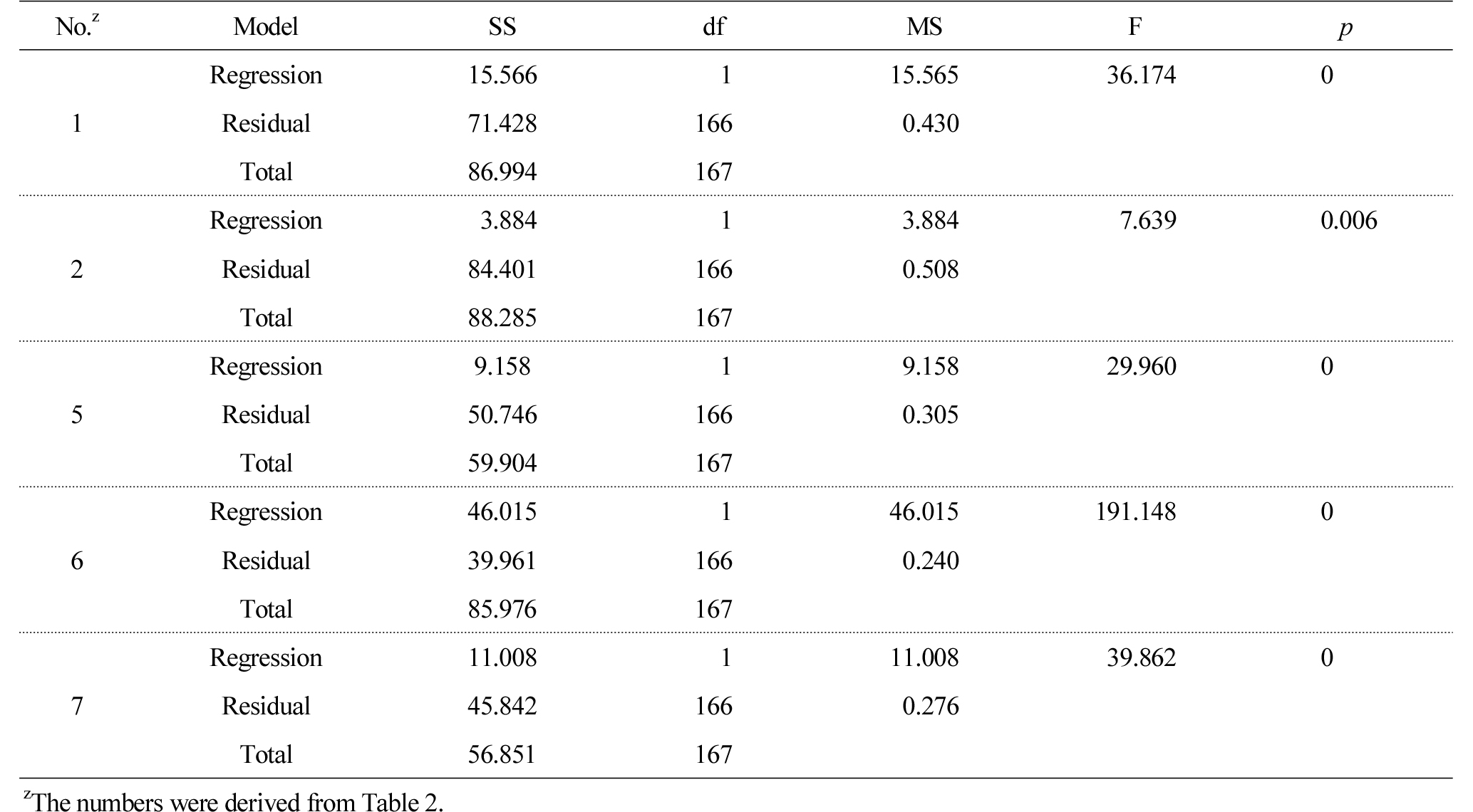

As a result of regression analysis (Table 4, Table 5), the gender difference in whether the school’s image improved after removing school walls (No. 1) had an explanatory power of 17.4% with significant effect. The gender difference in whether the school became more beautiful than before removing school walls (No. 2) had an explanatory power of 3.8% with significant effect. The gender difference in whether students talk more with friends after removing school walls (No. 5) had an explanatory power of 14.7% with significant effect. The gender difference in whether students are aware of strangers after removing school walls (No. 6) had an explanatory power of 53.2% with significant effect. The gender difference in whether students think there will be more crimes after removing school walls (No. 7) had an explanatory power of 18.8% with significant effect.

School is a place where students spend more than half of their everyday lives and is the center of community life. The school environment shall be able to fully perform its educational functions for students studying and growing within, and become a training center for spiritual culture and emotionally sound development as well as a venue for edification of local residents (Lee, 2008). Therefore, to bring and promote positive changes by removing school walls, it is necessary to carry out a greening project along with wall removal and link the project to elementary school curriculum, thereby activating field trips using school forests, vegetable gardens or flower beds, which will lead to internal stability of school education. Furthermore, it is necessary to properly manage the area such as replanting withered plants in time or refilling the created pond with water (Lee, 2008). It is also necessary to consider female students that are more sensitive by considering the emotional gap that clearly exists between male and female students.

Daegu has been the first in Korea to carry out the wall removal project in 1996 (Kim and Jeong, 2013). Celebrating its 20th anniversary in 2016, Daegu made a plan to continue the wall removal project based on the evaluation of the project that it has contributed to creating a communication culture among neighbors and building an environmentally friendly green city (DMC, 2016). To this end, Daegu decided to create a 363,548 m2 park by removing 30.8 km of walls in 864 places including 50 schools. The results of this study are consistent with the accomplishments of the wall removal project of Daegu and will be used as the baseline data for the project in the future.

Conclusion

This study conducted a survey on 168 sixth grade students (92 male and 76 female) at S Elementary School located in Daegu that carried out the school wall removal and greening project, in order to determine the satisfaction of elementary school students with school wall removal and greening. The results showed that the students were generally satisfied with school wall removal, and gave relatively more positive scores in the promotion of school’s image (4.24), school landscape improvement (4.21), and expansion of green space (4.06) on a 5 point scale. They also responded positively to increased chances for gardening or talking with friends. However, they were somewhat negative toward strangers (3.35) or crime occurrence (3.36). Meanwhile, a comparison of the perception gap between male and female students showed that there was no gender difference in overall satisfaction, but female students gave significantly higher scores regarding school’s image improvement or increased awareness of strangers (p〈 .001). They also gave significantly higher scores regarding the school landscape improvement, increased conversations with friends, and concerns over crime occurrence (p〈 .05). Therefore, it is necessary to seek ways to maximize the positive effects of removing elementary school walls and minimize the negative effects such as concerns over crime occurrence, while also considering female students that respond more sensitively about school safety.