A Meta-analysis of Horticultural Therapy Programs for Children: Focusing on Journal Articles

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

This study analyzed the effects of horticultural therapy programs for children using meta-analysis. It aims to provide logical grounds and basic data for practical intervention plans in educational settings.

Methods

For analysis, out of total 498 papers published in journals from 2000 to 2022 under the keywords ‘gardening (or horticulture) for children’ and ‘elementary gardening (or horticulture)’, 35 articles were finally selected and analyzed, excluding those redundant or integrated with other age groups or programs.

Results

First, the overall average effect size of horticultural therapy programs for children was 0.795, which was a medium size. Second, the average effect size for each dependent variable was the largest in the cognitive domain at 1.153, followed by the social domain, the psycho-emotional domain, and the physical domain. Third, the average effect size according to the grade of the subjects was the largest at 0.955 in the upper grades, followed by the lower grades and mixed grades. Fourth, as a result of meta-regression analysis, shorter time per session resulted in higher effectiveness of horticultural therapy programs for children (p = .001).

Conclusion

In this study, the meta-analysis results showed that the most effective way to increase children’s activity effectiveness in horticulture activities using plants is to conduct activities once a week, for 10 sessions or less, and with a time of less than 60 minutes per session.

Introduction

Horticultural activities are the easiest and closest way to experience nature, and are an effective means for children to effectively obtain emotions (Kwack and Kwack, 2000). Horticultural therapy using this horticulture as a medium is rapidly being proved effective in individual case studies and group programs for children.

Previous studies on horticultural therapy for children include studies by Han and Yoo (2014) and Jeong et al. (2014) conducted on children in general, as well as studies on all kinds of children such as those with disabilities (Sin and Lee, 2010; Yang and Kim, 2010), from low-income families (Sin, 2010; Yun and Choi, 2016), and from broken homes (Hwang et al., 2007; Lee and Kim, 2010). There are also studies on different variables according to the purpose of intervention, such as self-esteem (Kwack et al., 2015; Yun and Choi, 2016), sociality (Park et al., 2014; Lim and go, 2015), and stress (Kang and Lee, 2011; Cho and Kim, 2012).

Studies on horticultural therapy targeting children have diverse variables depending on the purpose of intervention and have been conducted using various interventions. It was necessary to generalize the study results of such horticultural therapy programs. Meta-analysis is a method of analysis that can more clearly reveal the study results through an integrated analysis of individual studies within a consistent system (Oh. 2002). Thus, identifying the objective effects through meta-analysis will contribute to the development of research on horticultural therapy for children in the future.

Previous studies that conducted meta-analysis of horticultural therapy include studies by Kim (2007), Jang (2010), and Choi (2020) on the overall effect and trends of horticultural therapy. Other studies include meta-analysis of horticultural therapy on specific subjects such as the elderly or patients with dementia (Kang and Kang, 2021; Bae et al., 2021), meta-analysis on variables such as psychological variables or improvement of self-esteem (Hong, 2006; Park, 2021), and meta-analysis on variables such as subject learning domain, cognitive function domain, and personality of students in each class from kindergarten to high school (Lee and Jeong, 2018). As horticultural therapy is studied more and more actively, research is conducted on diverse subjects and topics, and meta-analyses are also performed in various topics. However, there is no meta-analysis on horticultural therapy for children thus far. Accordingly, this study identified the variables affecting horticultural therapy for children through meta-analysis to come up with objective and scientific results based on this need. To more qualitatively determine the effectiveness of horticultural therapy, this study verified the effectiveness of horticultural therapy by symptom and examined the total number of sessions, number of sessions per week, and length of sessions suitable for each symptom, based on which it will be possible to standardize specialized horticultural therapy (Kim, 2007).

The purpose of this study is to investigate the research trends and effects of horticultural therapy and activity programs for children using the results of meta-analysis and provide logical grounds and basic data for research on horticultural therapy for children as well as for actual intervention plans in educational settings. To this end, the following research questions were set up. First, what is the general trend in research on horticultural therapy and activity programs for children? Second, what is the overall average effect size of horticultural therapy and activity programs for children? Third, what is the difference in the effect sizes of horticultural therapy and activity programs for children depending on moderating variables such as grade, population size, number of treatments, and length of each session?

Research methods

Data selection and collection process

To analyze the effects of studies on horticultural therapy and activities for children through meta-analysis, 35 articles that can be used in meta-analysis out of total 498 journal articles from 2000 to 2022 were selected as the subjects of this study. Research data was collected by searching articles related to horticultural therapy and horticultural activities by selecting search words ‘gardening (or horticulture) for children’ and ‘elementary gardening (or horticulture)’ on the Research Information Sharing Service provided by Korea Education and Research Information Service (KERIS) and Korea Citation Index (KCI) by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Out of 498 articles searched this way, the following criteria were set to perform secondary classification for metaanalysis. First, articles not related to horticultural therapy/activities or are not targeting children were excluded from meta-analysis. Second, even among articles related to the selected topic, the ones using a qualitative research method or that are combined with other therapy programs were excluded. Third, the articles that reveal statistical values, means, and standard deviations that can be converged to effect size were selected as the subjects of analysis. Out of 498 articles searched based on these criteria, 240 redundant articles were excluded. Then, 51 articles that were not related to horticultural therapy/activities were excluded, and then 45 others that were not targeting children or had subjects also in other age groups. In addition, articles that were not experimental studies and articles that integrated horticultural therapy with other programs were excluded. Finally, articles to which meta-analysis cannot be applied were excluded, ultimately leaving 35 articles, and the number calculated as effect size was 83.

Data input and analysis method

This study coded the study results of 35 selected articles using MS Excel. When coding the selected data, the number of samples (N), mean (M), and standard deviation (SD) of the pretest and posttest on the study results of the experimental group were entered for each variable of analysis. The coded results were analyzed using the meta-analysis program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) version 4.0.

All the study results were converted into Hedges’ g as effect size to reduce errors due to the small sample size. Since the articles each had different intervention methods and samples and were conducted independently, a random effects model was used to generalize and apply the study results to other groups. Meta-ANOVA and meta-regression were used to analyze the variables and domains of programs studied. Finally, the publication bias of articles for final analysis was reviewed to verify the validity of the meta-analysis results.

Then, effect size was interpreted using the following method. First, the 95% confidence interval of effect size was provided to verify the statistical significance when the confidence interval does not include 0 (Higgins and Green, 2008). Second, according to the criteria set by Cohen (1988), the value of 0.3 or below was interpreted as small effect size, 0.5 as medium effect size, and 0.8 or above as large effect size (Hwang, 2018).

Results and Discussion

Overall effect size of horticultural therapy programs for children

The number calculated as effect size from 35 articles selected based on the criteria set by this study was total 83. The overall average effect size for all horticultural therapy programs for children was 0.795, which showed a significant average effect as it did not include 0 at the 95% confidence interval. According to the standard set by Cohen (1988), the overall average effect size was close to 0.8, which could be interpreted as a large effect size (Table 1). This shows a value similar to the average effect size of horticultural therapy programs for children in the study by Choi (2020), which was 0.740, showing a medium effect size.

Average effect size by dependent variable

As a result of analyzing the effect size of each dependent variable (psycho-emotional, social, cognitive, physical domains) of horticultural therapy programs, it was found that the effect size of the cognitive domain was largest at 1.153 (p = .000). This was followed by the effect size of the social domain at 1.042, and the effect size of the psycho-emotional domain at 0.576, showing significance (p = .000). The effect size of the physical domain was 0.518, but had no significance (p = .597). The overall average effect size for each domain of the dependent variables showed no significance (p = .056). While many studies examined the psycho-emotional domain, the effect size was rather smaller than other domains (Table 2). This was different from the study by Jang (2010) in which the effect size was the largest in the physical domain in the case of children, followed by the social domain, emotional domain, and cognitive domain.

Average effect size by grade

The children participating in the study were classified into lower grades, upper grades, and mixed grades of elementary school based on their age standard for each grade. The lower grades were defined as Grades 1–3 or ages 7–9, and the upper grades as Grades 4–6 or ages 10–12. The results of analysis showed that the effect size of the upper grades was 0.955, which was larger than that of the lower grades at 0.807 and mixed grades at 0.656. Considering that the confidence interval was narrower in the studies on upper-grade students than lower-grade or mixed-grade students, it was found that research on upper-grade students was more effective (Table 3).

Average effect size by population size

As a result of analyzing the average effect size for each population size by grouping the participants into 10 or fewer, 11–20, 21–30, and 31 or more, the effect size was largest at 0.935 when there were 31 or more participants, and bigger populations had larger effect size and were more effective (p = .085, Table 4).

Average effect size by number of sessions per week

Effect sizes were compared by classifying the number of sessions of horticultural therapy for children per week into once a week, twice a week, others, and not indicated. The results showed that the effect size for once a week was 0.768, which was more effective than twice a week (Table 5).

Average effect size by total number of sessions

Effect sizes were compared by classifying the total number of sessions into less than 10, 11–20, and 21 or more. The results showed that the effect size was significant at 1.137 when the total number of sessions was less than 10 (p = .000), showing the largest effect size (Table 6).

Average effect size by length of each session

As a result of comparing effect sizes by classifying the length of each session of horticultural therapy for children into 60 minutes or less, 60–90 minutes, and 90 minutes or more, programs that were 60 minutes or less showed the largest effect size at 1.150 (p = .000). Programs that were 90 minutes or more showed the smallest effect size at 0.540 (p = .004). The heterogeneity of these effect sizes was Q = 10.195 (p = .017), indicating that there was significance in the difference in effect size according to the length of each session of horticultural therapy programs for children (Table 7). Horticultural therapy programs for children in which each session was shorter had larger effect sizes, which is contrary to the results of a meta-analysis of horticultural therapy targeting all age groups in which programs with longer sessions had larger effect sizes. This is consistent with the study results that programs in which the length of each session was less than 60 minutes showed the largest effect size (Kim and Jo, 2021) and the results that longer sessions tended to rather reduce the effect (Park, 2014), which is because, unlike adults, children have limited time in which they can pay attention (Kim and Jo, 2021).

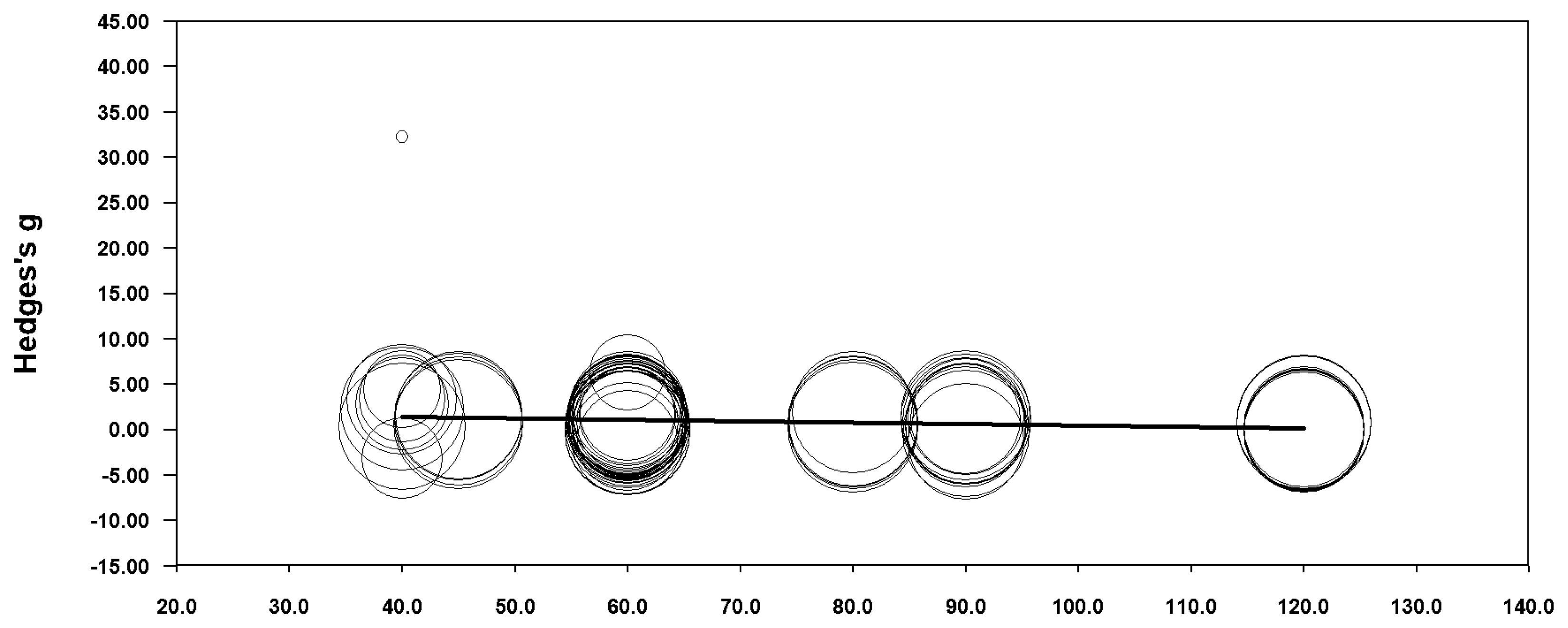

Meta-regression by length of each session

As a result of meta-ANOVA among the analyses on effect sizes of horticultural therapy programs for children, meta-regression was conducted with the length of each session, which has significance, as the predictor variable. The results of meta-regression according to the length of each session are as shown in Table 8 and Fig. 1.

The slope coefficient of the regression line according to the length of each session was −0.015, and the lower limit was −0.024 and the upper limit was −0.007. In other words, horticultural therapy programs for children with shorter sessions tended to show greater effectiveness (p = .001).

Publication bias

As a result of analyzing the funnel plot to examine the overall distribution of the individual effect sizes in this study, it was possible to visually identify that the effect size slightly deviated from bilateral symmetry around the straight line in the middle (average effect size) (Fig. 2). This indicates that there is publication bias in the study results.

To test additional publication bias, the trim and fill technique proposed by Duval and Tweedie (2000) was used for analysis. As a result, 6 studies were added, and the effect size showed a difference from 0.795 before to 0.678 after correction (Table 9).

The results of statistical analysis also show that the effect size is asymmetric. Thus, these results helped discover the risk of publication bias in this study. Publication bias like this occurs because a study with a small effect size is not significant and is thus likely to be not published, whereas a study with a large effect size is statistically significant and is thus published (Cho et al., 2013).

Conclusion

This study verified the effects of horticultural therapy programs for children through meta-analysis. To this end, this study analyzed 83 effect sizes from total 35 articles published in domestic journals, and the results are as follows.

First, the general trend of studies on horticultural therapy for children was as follows. There were 17 articles (48.6%) in 2011–2015, 14 articles (40.0%) on the upper grades of elementary school, 14 articles (38.9%) with the population size of 10 or less, 24 articles (72.7%) in which the number of sessions was once a week, 21 articles (60.0%) in which the total number of sessions was 11–20, and 15 articles (57.7%) in which each session was 60 minutes or less.

Second, the overall effect size of horticultural therapy for children was 0.795 (.612–.978), showing statistical significance. This could be considered a medium effect size based on the standard for effect size set by Cohen (1988).

Third, the average effect size of each depending variable was the largest in the cognitive domain at 1.153, followed by the social domain (ES = 1.042), psycho-emotional domain (ES = 0.576), and physical domain (ES=0.518).

Fourth, for the grade (age) of participants, which is the variable related to the experimental subjects, the effect size was the largest when the participants were upper-grade students. Moreover, the population size of children that participated was 10 or less (ES = 0.764), 11–20 (ES = 0.779), 21–30 (ES = 0.930), and 31 or more (ES = 0.935), indicating that bigger population sizes led to larger effect size and more effective. The effect size was the largest when the number of sessions per week was once a week (ES = 0.768), followed by twice a week (ES = 0.706) and others (ES = 0.628). However, as a result of meta-ANOVA, there was no significance among subgroups for age of participants (p = .433), population size (p = .085), and number of sessions per week (p = .186).

Fifth, length of each session among the variables related to program intervention showed a statistically significant difference in the meta-ANOVA, and the effect size was the largest when each session was 60 minutes or less. Moreover, even in univariate meta-regression, the length of each session turned out to be a significant variable that affects program effect size.

Sixth, as a result of identifying publication bias in this study, the study results for analysis turned out to have publication bias.

The results of this study suggest that, to increase the effect of children’s horticultural activities using plants, it is most effective to engage in activities once a week, total 10 sessions or less, and 60 minutes or less for each session instead of for a long period. This is contrary to the results from the meta-analysis of horticultural therapy targeting all age groups in which the effect size is larger when each session is longer, which is because children have limited time in which they can pay attention unlike adults (Kim and Jo, 2021).

Finally, this study is limited in that it failed to provide analysis results using various subfactors due to lack of related studies that are published. Another limitation is that it did not include unpublished articles or study results in the form of abstracts. Despite these limitations, this study has significance in systematically analyzing the articles published in domestic journals that studied horticultural therapy and activities for children and quantifying the effect sizes. Based on the limitations of this study, further research must analyze the effect sizes according to the suitable population size for each symptom as well as the number and length of sessions, including research findings from dissertations and abstracts. By organizing and implementing horticultural therapy programs with conditions suitable for each symptom, it will be possible to increase the effect and expertise of horticultural therapy for children.