Influence of Cultural Landscapes on Visitors’ Behavior in the Context of COVID-19 Social Distancing Policies: A Case Study of Open Public Spaces Inside Gyeongbok Palace

Article information

Abstract

Background and objective

Many studies have highlighted the psychological benefits of natural outdoor environments and cultural heritage sites for visitors. However, few studies have investigated the combined impact of natural outdoor settings and cultural heritage sites considering contextual factors such as gender, age, time of day, and period on visiting patterns. This study aims to identify the impact of cultural landscapes on visiting patterns, focusing on the open public spaces of Gyeongbok Palace, Seoul.

Methods

A mixed-method approach was used to examine the association between cultural landscape elements and visiting patterns. Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were employed to assess how the cultural landscape affected visiting patterns from 2019 to 2021, considering the impact of COVID-19 social distancing policies. An on-site visit observation and analysis of previous case studies were conducted to further investigate the impacts of cultural landscape elements on visitors’ behavior patterns.

Results

The findings indicated that the cultural landscape played a role in shaping visitors’ behaviors and revealed significant variations in visitation patterns based on visitors’ age and the day of the week. A strong positive correlation was observed between teenagers and weekday visits, especially in 2020 when COVID-19 restrictions were in place and students were taking online classes. Furthermore, the results showed a noticeable increase in correlation scores in 2021 compared with those in 2019, supporting the notion of heritage sites serving as healing and relaxing places for people to enjoy as they age.

Conclusion

The study findings provide an empirical basis for studying cultural heritage assets and other natural outdoor environments as a type of cultural landscape to enhance visitor satisfaction and provide positive benefits to visitors. It highlights the importance of preserving and promoting cultural landscapes as integrated systems of natural and cultural resources, which can be applied to heritage policies and management strategies.

Introduction

People’s well-being, quality of life, and life satisfaction have recently become a policy priority in many countries (Jang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2016; United Nations, 2020). The United Nations (2022) established the Sustainable Development Goals to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being. Globally, policies are changing to improve the quality of life using health and environmental indicators (Lee et al., 2016). In parallel, the South Korean government has created initiatives to enhance citizens’ quality of life and tools such as the “Korean Quality of Life Index” and “Index of Well-being in Culture and Leisure” (Jang et al., 2019). For example, South Korean cities are implementing policies to improve their residents’ quality of life by providing free access to urban cultural heritage sites, allowing more people to enjoy these sites and improve their mental health (Lee, 2008). As a result, scholars are increasingly studying the impact of natural outdoor environments on the quality of life in a cultural heritage setting (Alcindor et al., 2021; Lowenthal, 2015; Sung and Brooks, 2022).

Many environmental psychology studies indicate that outdoor environments with natural settings, such as community parks, gardens, trees, and green vegetation, have positive psychological benefits, such as providing better mental health and well-being (Kjellgren and Buhrkall, 2010; Koning et al., 2022; Nutsford et al., 2013; Ulrich, 1981, 1983; Wells and Evans, 2003). In particular, Koning et al. (2022) found that some elements, such as residents’ neighborhood greenness, walking outdoors, and views of nature, are related to good mental health. Similarly, Ulrich (1981, 1983) revealed that views of nature, including water, profoundly influence people’s emotional states. They lead to feelings of well-being, relaxation, stress reduction, and resilience to the stress arising from busy, modern, and urban life (Kjellgren and Buhrkall, 2010; Nutsford et al., 2013; Ulrich, 1983; Wells and Evans, 2003).

White et al. (2019) highlighted that just two hours of contact with nature every week improves health and well-being. Houlden et al. (2019) found that greenspace within a radius of 300 m is associated with improved mental well-being. Further, Hazen (2009) reported that 88% of study respondents were willing to participate in certain park activities because of the potential scenic views. The literature indicates that community parks and gardens that resemble natural outdoor environments connect humans and nature (Hung and Chang, 2021; Kaplan and Rogers, 2003; Park and Jeong, 2020). This contact with nature reduces negative emotions, such as anxiety, anger, and sadness, and arouses positive emotions, such as pleasure, joy, and satisfaction (Jang et al., 2020).

Notably, the number of urban residents who hope to relax and experience nature in their residential spaces has recently increased (Park and Jeong, 2020), especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus drastically affected people’s lifestyles, as it introduced the concept of working from home and social distancing, all of which reduced the possibility of enjoying the benefits of nature (Hung and Chang, 2021; White et al., 2019). Consequently, mental health and well-being have emerged as primary concerns in the post-COVID-19 era (Koning et al., 2022). Thus, several recent studies have argued that natural outdoor environments can play a positive role in mediating the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mental health (Kjellgren and Buhrkall, 2010; Szpakowska-Loranc, 2021).

For instance, Hung and Chang (2021) highlighted that more people have started to understand the importance of natural outdoor environments and visit their nearby green spaces, compared to before COVID-19. Notably, Choi (2021) and Ban (2021) reported that, in South Korea, 49.3% of 520 surveyed office workers spent their time after meals walking outdoors near green spaces. Lee (2020) suggested that after the outbreak of COVID-19, office workers tended to choose green spaces such as community parks and nearby cultural heritage sites to take walks in during lunchtime.

Consequently, among various types of green infrastructure, community parks can be the most important provider of psychological benefits for people living in urban settings (Kim and Miller, 2019), especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Ban, 2021; Choi, 2021; Lee, 2020). Community parks can encourage people to spend more time in natural outdoor environments and open public spaces, resulting in relaxation, stress relief, improved mental health, and social interactions (Kim and Kaplan, 2004; Ulrich, 1983). Thus, Lopez et al. (2020) argued that people might favor parks and green spaces—comprising trails, trees, shading, seating, landscaping, and water—as vital for physical and mental health.

The aforementioned literature suggests that community parks play an important role in promoting quality of life by serving as spaces for visitors to exercise and engage in social interactions. They also ease visitors’ anxiety and instill a sense of pride in the site (Kim and Miller, 2019). In this context, this study views community parks as garden or parkland landscapes constructed for visitors to improve their well-being and ease their everyday anxiety, being one of the essential cultural landscape elements (World Heritage Centre, 2021).

Compared with the role of outdoor environments in a natural setting, Lowenthal (2015) argued that cultural heritage serves as an “anchor” or “root” against the rapid pace of contemporary life, whereas Huyssen (2003) claimed that people hold on to public spaces associated with a memorable event, especially in urban settings, as they do not wish to lose reminders of their history. This enables visitors to form a sense of attachment to certain places. Moreover, cultural heritage sites can work geographically as urban landmarks, endowing them with a unique character and, ultimately, contributing to a sense of place (Abdurahiman et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2016). The power of urban cultural heritage sites lies in creating a sense of place within a community (Abdurahiman et al., 2022; Shackel, 2001) because it can provide a network of references and unique identity, helping individuals form an emotional attachment to a place (Alcindor et al., 2021), which can contribute to their quality of life (Kim and Miller, 2019).

Power and Smyth (2016) suggested that local cultural heritage sites can have various positive benefits for visitors, including for those who live in densely populated urban settings, because they are places where city dwellers can relax. According to the 2018 South Korean Cultural Heritage Administration survey results, 62.4% of respondents reported that cultural heritage sites made them feel relaxed, scoring 3.68 out of 5 on average (Hyundai Research Institute, 2018). Moreover, 57.4% answered “yes” to whether seeing cultural heritage sites made them feel better, with an average of 3.58 points (Hyundai Research Institute, 2018). These results indicated that more than half of the respondents, regardless of age, agreed that cultural heritage could positively influence their quality of life. Notably, South Korean temple stay programs became famous, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as places of healing and relaxation (Newsis, 2021). In addition, Sung and Brooks (2022) offered empirical evidence supporting this claim. Their study discovered that national heritage sites in Seoul influenced social environmental satisfaction indices (Sung and Brooks, 2022). This suggests that residents of Seoul may have a preference for living in close proximity to these sites, such as the Gyeongbok Palace, and frequently visit them.

It is clear from the preceding paragraphs that natural settings and cultural heritage offer significant benefits for people’s well-being and quality of life. However, few studies have fully explored the impact of the combination of natural settings with cultural heritage on people’s well-being and quality of life by considering various contextual factors, such as ethnographic traits, demographic characteristics, time of day, season, and life stages (Ababneh, 2021; Alcindor et al., 2021; Houlden et al., 2019; Stegmeijer et al., 2021), with a particular focus on smaller-scale environments, such as heritage or historical sites (McIntosh, 1999). Future heritage policies should investigate the impact of cultural landscapes on visitors’ behavior to improve the quality of people’s lives (Jang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2016; Stegmeijer et al., 2021; United Nations, 2020). The negative influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mental health and quality of life should also be considered (Ban, 2021; Choi, 2021; Lee, 2020). This study aims to provide empirical evidence regarding the diverse impacts of a cultural landscape on visiting patterns, after considering gender, age group, time of day, and periods. It provides an experimental model to evaluate visitors’ consumption patterns. This study bridges the gap in previous research by focusing on the open spaces of Gyeongbok Palace to answer the main research question: How does the cultural landscape influence visitors’ behavior?

Gyeongbok Palace is one of the most visited cultural heritage sites in South Korea. It has two visitor areas: one requires an admission fee for entry, and the other can be accessed by anyone, even without a ticket. This study focuses on the latter to control for the influence of visitors’ financial difficulties (Rahim and Marva, 2009) and their willingness to pay. Moreover, several Gyeongbok-based studies have found a good balance between the nature and cultural heritage of the palace. Based on these rationales, the open public area of Gyeongbok Palace, an important cultural landscape element (Sauer, 2007), was selected for the case study. The study adopted quantitative and qualitative approaches to examine the impact of the cultural landscape on visiting patterns, taking into consideration various contextual factors such as gender, time of day, period, and age groups. Qualitative methods—an on-site observation and analysis of previous case studies—were employed to complement the quantitative data-driven approach.

Research Methods

Theoretical framework

Although natural and cultural heritage sites evoke different psychological reactions, several studies indicate that these could be interconnected and partially inseparable (Council of Europe, 2000; Lowenthal, 2015). For example, Lowenthal (2015) argued that natural wonders and historic splendors are similarly considered and utilized, just as eco-tourism and cultural travel are increasingly combined. Additionally, numerous studies have concluded that a landscape’s natural and cultural potential is significantly related to visitors’ behavior patterns, experiences, and revisit intentions (Jang et al., 2020; Ramkissoon et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2007).

Consequently, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) introduced the concept of cultural landscapes in 1992 to represent the combined efforts of nature and humans (Jiang et al., 2022; Lowenthal, 2015; World Heritage Centre, 2021), highlighting the importance of contextualizing contemporary architecture in the inherited townscape. Sauer (2007) also pinpointed that the acknowledgment of interconnectedness between natural and cultural heritage has evolved into the concept of “cultural landscape,” whose character is shaped by the interaction of humans and natural elements (Council of Europe, 2000). Among the three types of cultural landscapes shaped by UNESCO, the most recognizable is “the clearly defined landscape designed and created intentionally by people, embracing garden and parkland landscapes constructed for aesthetic reasons, often associated with religious or other monumental buildings and ensembles” (World Heritage Centre, 2021, pp. 22–23). The site selected for this study combines parkland landscapes with monuments and fits the definition of a cultural landscape.

Cultural landscapes are increasingly utilized and appreciated by visitors. However, there has only been limited exploration of the spatial relationship between visitor behavior patterns and the elements of cultural landscapes (Oliver, 2001). Consequently, previous studies have found that studying visitor behavior patterns can elicit the spatial relationship of how individuals form emotional ties with a particular place (Alcindor et al., 2021; Proshansky, 1978). For instance, Proshansky (1978) suggested that we can understand how an individual perceives the built environment around them by observing their behavioral tendencies. McIntosh (1999) and Avrami et al. (2000) argue that researching visitor behavior patterns at heritage sites can improve visitor experiences and foster a greater understanding of the site value. Hong et al. (2020) also suggest that place attachment is developed through a continuous process of interaction between visitors and all the inherent attributes of a place, as well as the external elements. Therefore, visitors’ experiences and understanding of a site’s importance are related to generating a psychological impact and place attachment (Jang et al., 2019; Kim and Miller, 2019).

Research site

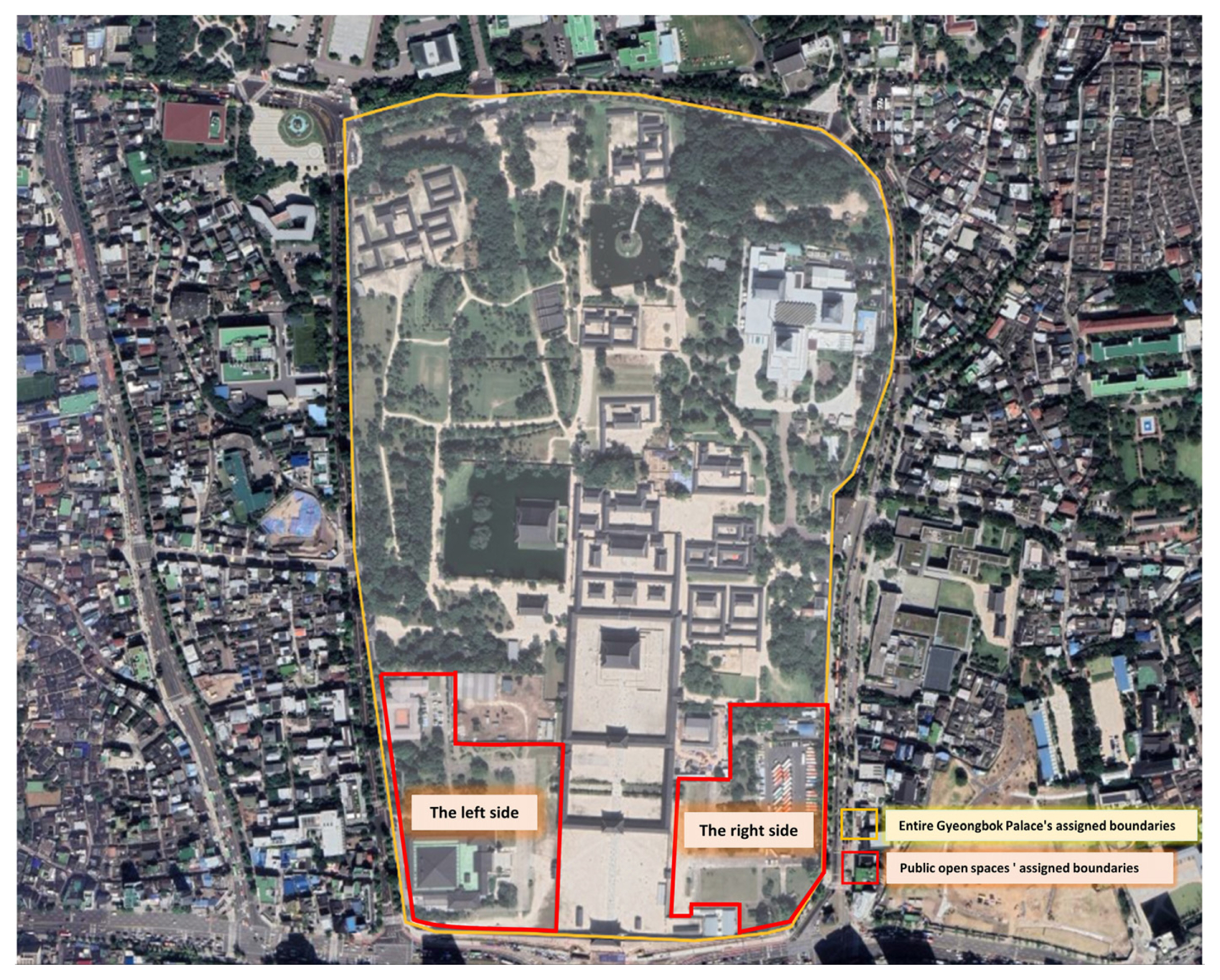

Gyeongbok Palace has been one of the most frequently visited cultural heritage sites in South Korea (Fig. 1), especially before social distancing policies were implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Korean Statistical Information Service (2022) revealed that more than five million people visited the Gyeongbok Palace in 2019, demonstrating its popularity compared with that of other nearby major heritage sites (Table 1).

Aerial image of public open spaces within Gyeongbok Palace’s assigned boundaries.

Note. Aerial image of Gyeongbok Palace was created using Google Earth.

Within the premises of Gyeongbok Palace (marked by the yellow outline in Fig. 1), there are two areas: one can be accessed by anyone without a ticket (highlighted by the red outline in Fig. 1), and the other requires an admission fee to enter. The entrance fee is 3,000 won (South Korean currency), equivalent to £2. However, if the visitor is younger than 24 years or older than 65 years, entry is free. As seen in Fig. 1, within the public open spaces of the palace marked by the red outline, two main areas can be connected or separated interchangeably. Usually, these two areas are connected during visiting hours and are disconnected after visiting hours (18:00). These public places are open until 20:00, while the remaining paid areas close at 18:00. The left side of the open public space is accessible to visitors until 22:00 on Wednesdays and Saturdays. This study focuses on the open public spaces of the palace (marked by the red outline in Fig. 1) because the number of visitors to the area may be restricted due to the cost of admission fees (Rahim and Marva, 2009). These spaces can be divided into the right or left sides of the area (Fig. 2).

Analytical approach

Significant scholarly attention has been paid to analyzing visiting patterns using statistical skills (McKercher et al., 2012; Wolf et al., 2015; Wolf et al., 2018). McKercher et al. (2012) utilized a geographic information system to access high-quality information concerning visitors’ spatial and temporal patterns. Wolf et al. (2015) contended that the analysis of visitors’ patterns may provide a cost-effective strategy to facilitate spatial decision-making and visitor management strategies. Thus, utilizing the data on visitation patterns facilitates the acquisition of comprehensive spatial knowledge of visitors’ activities within a defined geographic framework (Wolf et al., 2018). Valuable information and insights can emerge from closely examining the spatial relationship between people and their built environment. In particular, it allows us to monitor change and development, forecast trends, and identify key future priorities for the heritage site (Sieber, 2006).

Secondary datasets of visitors’ monthly movements were collected to account for gender, visiting time of the day, days of the week, and age group using the KT “BigSight” data platform—the “KT Big Data Intelligence Platform.” This provides insight into a customer’s business through KT’s various Big Data and analytics technologies (KT Corporation, 2016). The KT “BigSight” data platform only shares anonymized secondary data sets to protect the participants’ privacy. This meets the ethical requirements of collecting and using mobile phone data for research purposes. Using this platform, this study analyzed mobile phone data to investigate the impact of cultural landscapes on visiting patterns; descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficient analysis were employed. The formula of Pearson correlation coefficient can be depicted as

where r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, xi or yi is the value of the monthly number of visitors with a particular gender, time of day, period, or age group, and χ̄ or ȳ is the mean of the values of the monthly number of visitors with a particular gender, time of day, period, or age group.

Furthermore, this study conducted both an on-site visit observation and an analysis of previous case studies, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches to explore how the cultural landscape influences visiting patterns. On-site visits were employed to gather first-hand information and insights by being physically present and interacting with visitors, with a focus on understanding how they valued the research site. The first-hand information collected was recorded in the research diary, and analyzed thematically to gain a deeper understanding of how visitors appreciated the site and to critically interpret the findings of the study. In addition, the author of this study has lived in a nearby town since 2018, which has enabled them to have access to numerous informal meetings and discussions with, as well as observations of, the people who visit Gyeongbok Palace. Articles about Gyeongbok Palace from 2006–2017 related to tourism, people’s appreciation, and experiences of the palace were also collected and studied. Consequently, this study included a review of previous case studies of Gyeongbok Palace and on-site visits to further investigate the impact of cultural landscape elements on visitors’ behavior patterns. Thus, the collected qualitative data were not separated from the context, suggesting that the data were still embedded within the context in which they were gathered, allowing for a deeper understanding of how visiting patterns are influenced by the cultural landscape (Sanetra-Szeliga et al., 2015).

Finally, this study considered the COVID-19 social distancing policies, which profoundly influenced visiting patterns. After the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020), the South Korean government introduced a strict social distancing policy. As part of this, most public facilities had to be closed. Although not a complete shutdown, almost all non-working face-to-face activities, including leisure activities, were restricted (South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2020). In November 2020, the South Korean government shaped a new social distancing policy, which defined five levels of danger to lower the level of restriction on visitors (Kim, 2021). Thus, this study separated the analytical period into the three periods of 2019, 2020, and 2021 to consider the significant impact of social distancing policies on visiting patterns. Detailed information on the data is presented in Table 2.

Results and Discussion

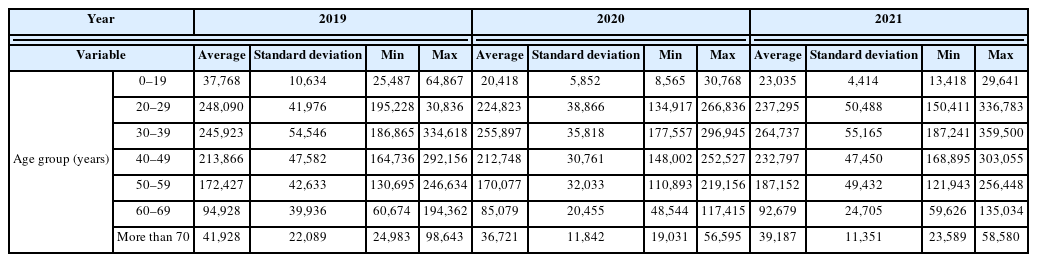

Table 2 shows the primary descriptive data on visiting patterns in the open public spaces of Gyeongbok Palace from 2019–2021. The number of visitors in their 20s–50s was higher than that in other age groups, such as those in their teens, 60s, and 70s (Table 2). Further, the number of visitors fluctuated from year to year. As shown in Table 2, the highest number of visitors was recorded in 2019, followed by the second highest in 2021 and the lowest in 2020, suggesting that social distancing policies profoundly influenced visiting patterns, as can also be seen in Table 1.

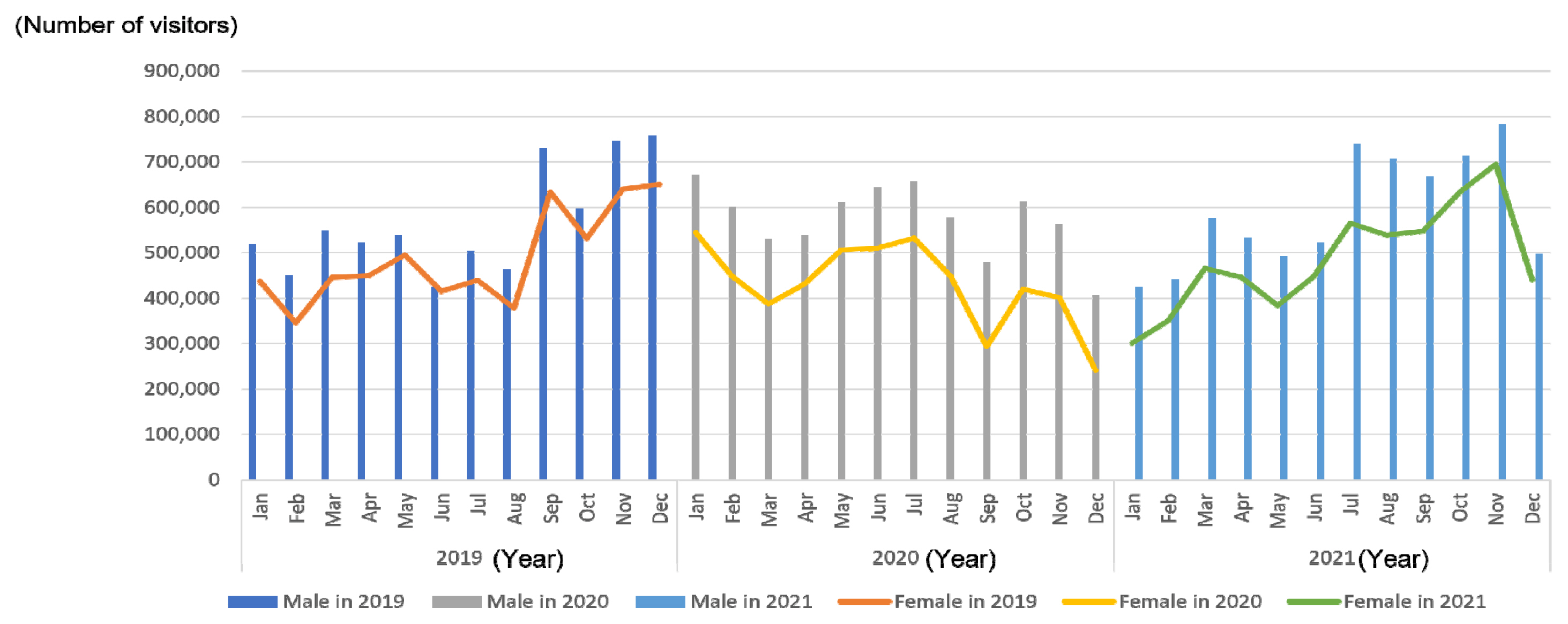

As shown in Fig. 3, the South Korean government introduced a social distancing policy restricting people’s meetings, visits to cultural facilities, and other social gatherings in March 2020. Thus, the number of visitors fell significantly from 918,601 to 647,509. However, from November 2020, the number of visitors increased considerably until November 2021, when the government eased social distancing policies. This study further analyzed the impact of visitors’ gender, time periods, and age on their visitation movements.

Number of visitors from 2019–2021 during COVID-19 restrictions.

Note. Data sourced from KT Corporation (2016) and Statistics Korea (2023)

No notable differences were observed in the visiting patterns based on gender, showing that the impacts of COVID-19 social distancing policies over the three years were the same across the two genders (Fig. 4). To clarify the results, considering the impact of COVID-19 social distancing policies, a correlation analysis was also conducted on the number of male and female visitors in relation to period and age.

Number of visitors according to gender from 2019–2021.

Note. Data sourced from KT Corporation (2016)

The most frequently visited time was from 14:00 to 17:00. The second was during lunchtime, from 11:00 to 13:00, and the third was from 18:00 to 20:00 and from 06:00 to 10:00 when morning exercise usually takes place (Fig. 5). The public spaces opened at 06:00 and closed at 20:00. However, it was unclear from this result how the social distancing policies impacted people’s visiting times. Thus, a correlation analysis by year was conducted, including the time of day as a factor in the analysis.

Number of visitors depending on time periods from 2019–2021.

Note. Data sourced from KT Corporation (2016)

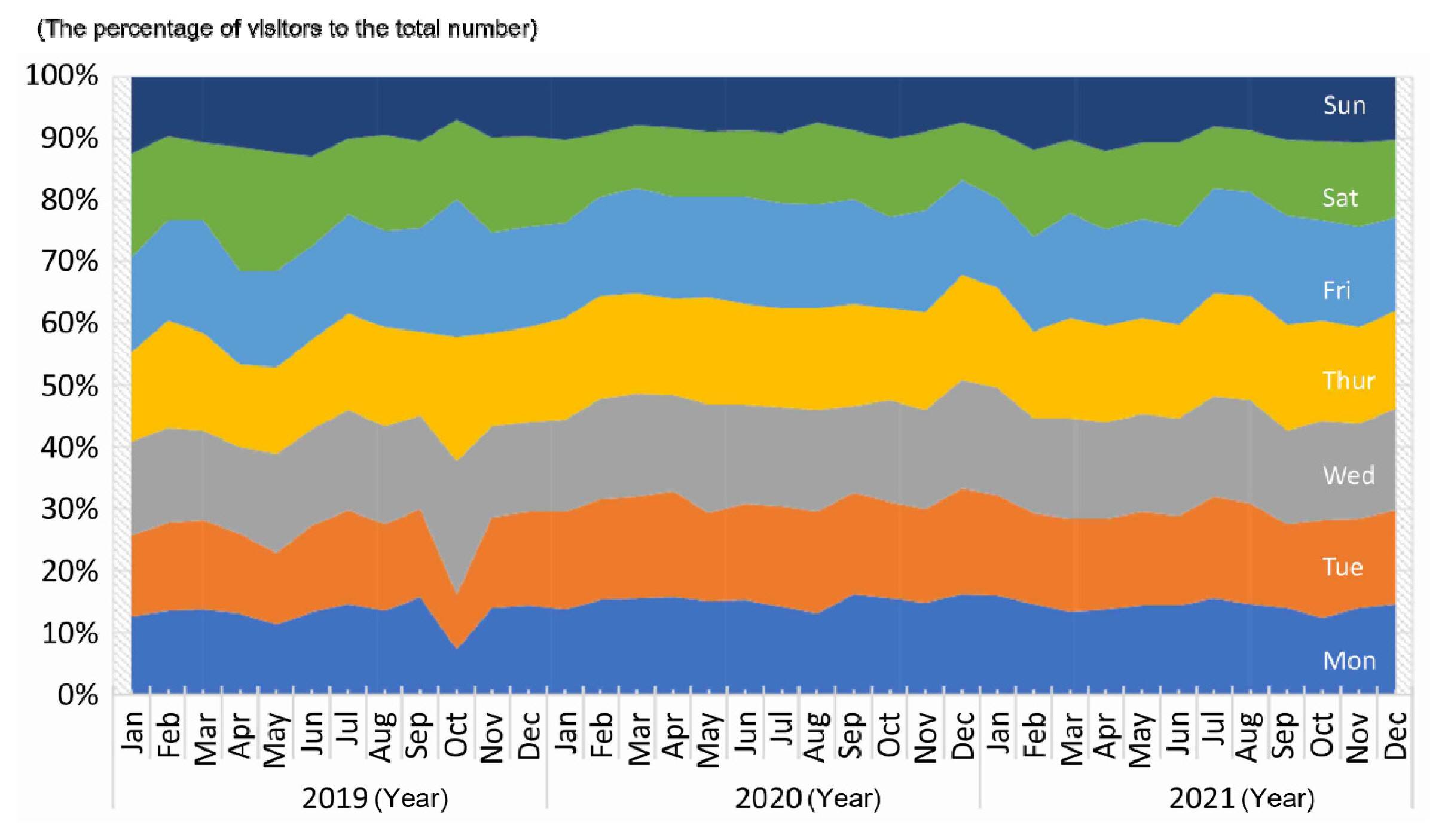

An analysis of the number of visitors to the study site per day (Fig. 6) showed that, overall, a few differences existed between the visiting patterns depending on the day of the week over time. Moreover, an analysis of the yearly patterns revealed differences in the number of visitors to the open public places of the palace in response to changes in COVID-19 social distancing restrictions. This study also conducted a correlation analysis of data from 2019, 2020, and 2021, considering the day of the week.

Number of visitors by day from 2019–2021.

Note. Data sourced from KT Corporation (2016)

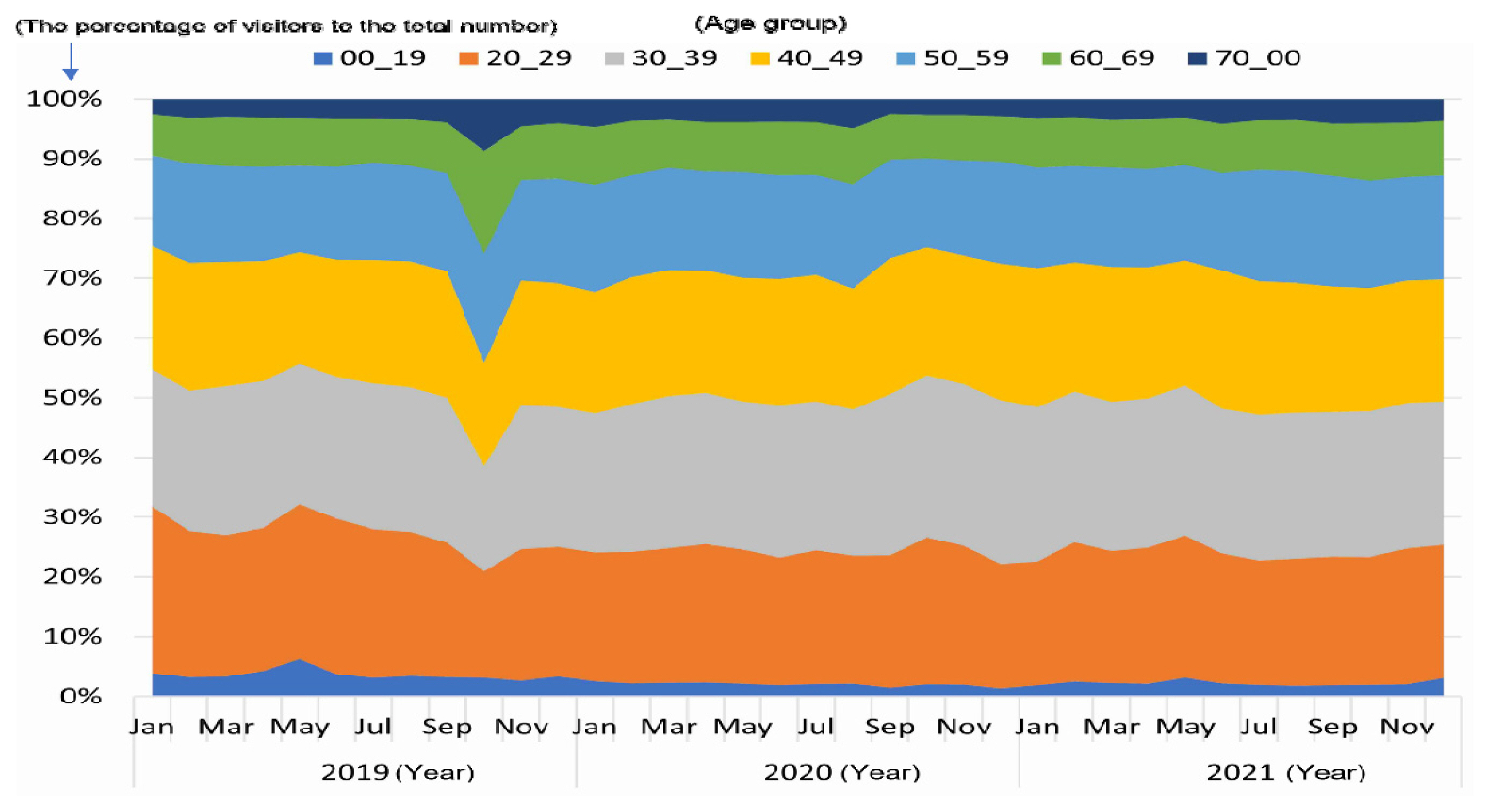

As shown in Fig. 7, people in their 20s–50s mainly used open spaces, whereas teenagers and those in their 60s and older did not use them often. Teenagers rarely visited open spaces because of school demands and extracurricular activities. This result also confirms that people in their 20s and 30s often visit open public places as dating or social venues. They usually wear traditional Korean clothing called hanbok (Bae, 2018), which can be rented easily at an affordable price in nearby clothing shops and enables them to enter the paid area of Gyeongbok Palace for free. To further elaborate on this result, this study involved an on-site visit observation and an analysis of previous case studies to accurately analyze the impact of cultural landscapes on visiting patterns.

Number of visitors according to age group from 2019–2021.

Note. Data sourced from KT Corporation (2016)

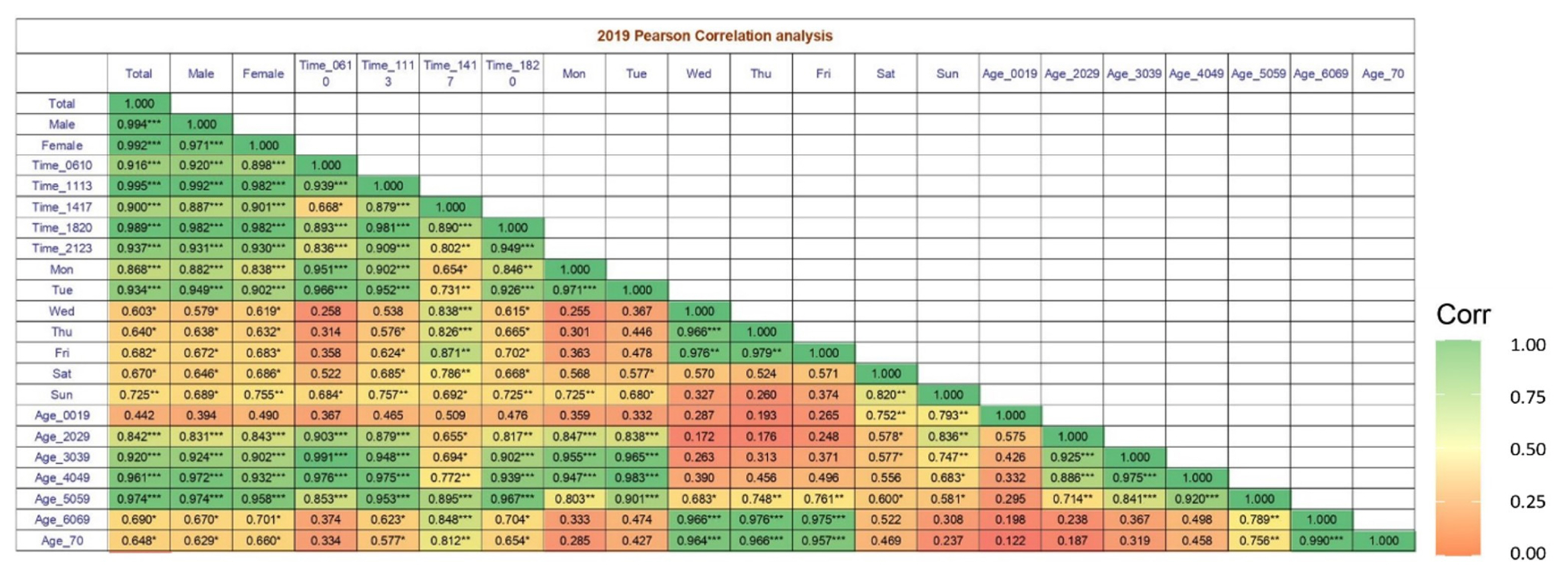

Fig. 8 reveals captivating patterns across diverse age groups and time periods regarding the relationship between the factors in 2019. Primarily, the data indicated that teenage individuals exhibited the lowest correlation scores, implying that the demands of school may have exerted a negative influence on the frequency of their visits, particularly on weekdays. However, a conspicuous upswing in correlation scores was observed during weekends, suggesting that school obligations wielded diminished sway during these periods. Second, most visits occurred during lunchtime (11:00–13:00) and post-work hours (18:00–20:00). Mornings (06:00–10:00) registered lower correlation scores from Wednesday to Friday, but presented higher scores among individuals in their 20s–50s, implying that these age groups predominantly used these public spaces for morning exercise regimens on either Mondays or Tuesdays.

Results of correlation analysis for 2019.

Note. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p <. 001. “Total” denotes the total number of visitors. “Male” and “Female” denote the monthly number of male and female visitors, respectively. Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat, and Sun denote the monthly number of visitors on each day. Time_0610, Time_1113, Time_1417, Time_1820, and Time_2123 denote the time of the visitors’ movements. Similarly, Age_0019, Age_2029, Age_3039, Age_4049, Age_5059, and Age_6069 represent the number of visitor movements for each age group. Age_70 is the movement data for those aged over 70 years.

Individuals in their teens and those aged 60 and above exhibited diminished correlation scores during most time periods. However, during lunchtime, heightened correlation scores were evident among individuals aged 20 and above, indicating that nearby office workers frequently visited these locations for relaxation and well-being (Ban, 2021; Choi, 2021). Subsequently, the analysis uncovered elevated correlation scores among older age groups, notably those in their 60s and older, during the afternoon hours (14:00–17:00), relative to individuals in their 20s. Furthermore, the correlation analysis highlighted Monday and Tuesday as the most frequented days by individuals in their 20s–50s, while Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday recorded diminished visitation rates within this age bracket. Conversely, individuals aged 60 and above demonstrated the highest visitation rates from Wednesday to Friday.

Fig. 9 shows the results of the correlation analysis of the data from 2020. Contrary to the 2019 correlation analysis, the results indicated that teenagers were positively correlated with their visiting periods and the weekdays’ variables. Teenagers likely visited the site in 2020 because most of their school classes were online, allowing them to use their time freely. Moreover, there was a noticeable general increase in the correlation score during weekends for those aged 20 and above, unlike the 2019 correlation analysis. As evidence of this, Kim et al. (2021) revealed that people visited the park to seek connection with others and promote physical activity and self-management despite fears of COVID-19 infection, using in-depth interviews of older male visitors at Tapgol Park. Thus, a possible interpretation of this result is that people had emerging needs and interests in cultural heritage sites as public places for their well-being, despite the possible danger of encounters with others.

Results of correlation analysis for 2020.

Note. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. “Total” denotes the total number of visitors. “Male” and “Female” denote the monthly number of male and female visitors, respectively. Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat, and Sun denote the monthly number of visitors on each day. Time_0610, Time_1113, Time_1417, Time_1820, and Time_2123 denote the time of the visitors’ movements. Similarly, Age_0019, Age_2029, Age_3039, Age_4049, Age_5059, and Age_6069 represent the number of visitor movements for each age group. Age_70 is the movement data for those aged over 70 years.

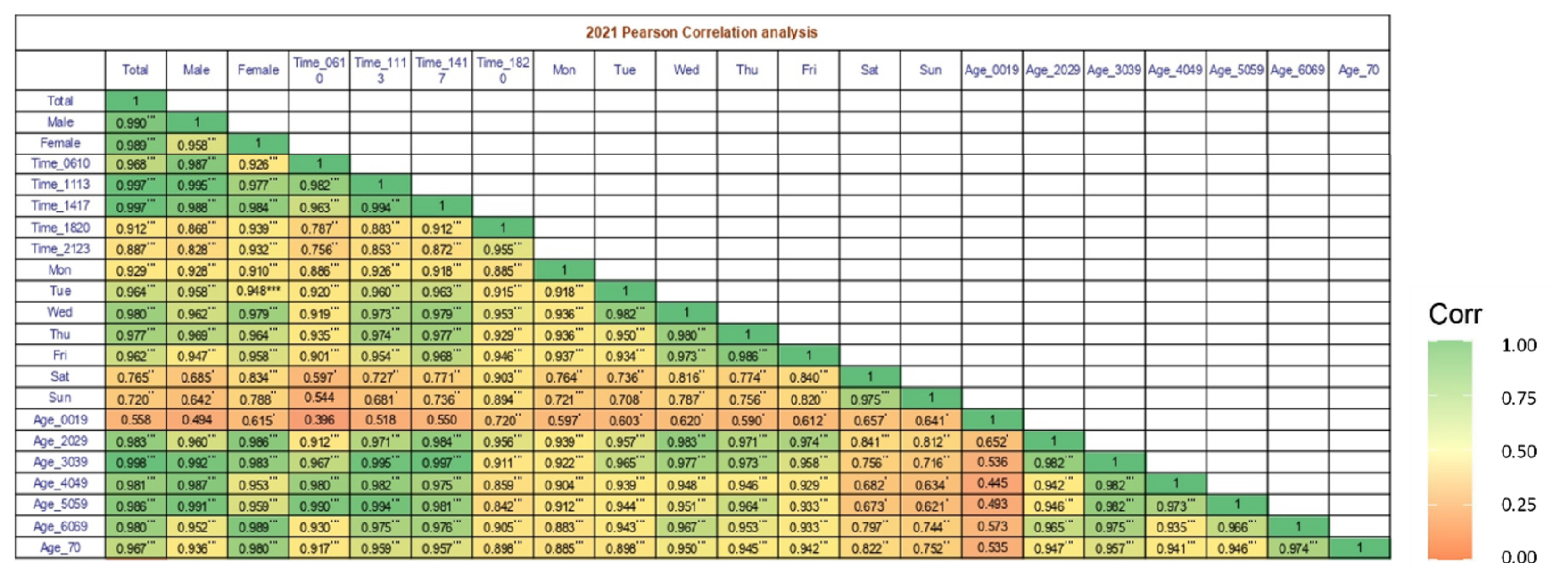

Fig. 10 shows the results of the correlation analysis of the data from 2021. Notably, the results showed trends similar to those of 2019 in terms of the visiting patterns of teenagers. Nevertheless, there were a few differences. First, the results suggested that the number of those in their 60s or 70s was highly correlated with their visiting periods and days of the week, implying that the groups of older adults placed significant value on cultural heritage sites for their well-being and overall quality of life. In contrast, the number of those in their teens was no longer statistically correlated or had lower correlation scores, unlike the results of 2020, indicating that they may not have had the time to visit anymore as they needed to attend in-person classes again. Furthermore, those aged 60 and above showed high positive correlation scores compared to the 2019 correlation scores. This phenomenon may have emerged due to the relaxation of social distancing policies and increased demand for green spaces, which could play a role in older adults’ preferences for public spaces such as Gyeongbok Palace.

Results of correlation analysis for 2021.

Note. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. “Total” denotes the total number of visitors. “Male” and “Female” denote the monthly number of male and female visitors, respectively. Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat, and Sun denote the monthly number of visitors on each day. Time_0610, Time_1113, Time_1417, Time_1820, and Time_2123 denote the time of the visitors’ movements. Similarly, Age_0019, Age_2029, Age_3039, Age_4049, Age_5059, and Age_6069 represent the number of visitor movements for each age group. Age_70 is the movement data for those aged over 70 years.

The analytical results given above highlighted that people who frequently visited the palace were aged over 20 years, implying a higher attractiveness of open public spaces for their relaxation and well-being. Importantly, these three-year results revealed that teenagers did not seem influenced by cultural landscapes in 2019 and 2021. A likely explanation was that schools adopted content-based education in 2020 to minimize the number of COVID-19 infections (Kwon, 2021), resulting in students not having to attend in person and having full control over their study time. However, in 2021, schools turned to a hybrid type of education by adopting Zoom as the primary mode of instruction, requiring students to be present in person when online classes were running. This partial return to normalcy ultimately influenced teens’ visiting patterns, resulting in patterns similar to those in 2019. South Korean teens likely spent most of their time pursuing academic work and extracurricular activities; thus, lack of time for visiting cultural facilities could have been a primary reason for this result.

These analytical results were re-confirmed using the KT “BigSight” data platform’s own analytical and systematic infographics (Fig. 11). By analyzing the “visiting patterns,” that is, how people moved around the open public spaces of Gyeongbok Palace, this study enables readers to visualize the consequent geospatial information (Longley et al., 2005). The research involved people of different age groups and their visiting patterns, so that the impact of the cultural landscape on different generations could be understood by conducting descriptive statistics and correlation analysis using R programming language. However, because of the impact of public social distancing policies, the cultural landscape may not have influenced the same visiting patterns in 2020 compared with those in 2019 or 2021. The researcher further conducted an on-site visit observation and an analysis of previous case studies, finding that visitors enjoyed the cultural landscape more during and after the COVID-19 social distancing restrictions implemented in 2020.

Visiting patterns in open public spaces in KT “BigSight” data platform.

Note. Adapted from KT Corporation (2016). Copyright 2022 by KT Corporation (https://bigsight.kt.com/bdip/components/portal/index.html#/portal/intro/trade). Adapted with permission.

Several Gyeongbok Palace case studies have acknowledged that a sense of history and being connected to nature positively influence the perceived emotional and economic values, ultimately affecting overall satisfaction (Song, 2012; Suh and Kim, 2013). This implies that the harmonious existence of natural and cultural heritage may positively attract people and influence their visiting patterns. This was evident in the higher correlated scores among the analytical results of the age groups in Figs 8, 9, and 10. For example, Suh and Kim (2013) suggested that visitors’ preferences increased as modern elements of the space decreased and natural elements increased. This highlights the importance of harmony between natural and cultural elements in a cultural landscape. Therefore, this study argues that the components of natural and cultural heritage as a type of cultural landscape produce synergetic positive effects on visiting patterns, expressed in the form of a higher frequency of visitor movements (Kim and Miller, 2019).

In summation, Lowenthal (2015) suggests that nature and antiquity are realms apart from the everyday present. Moreover, the elements constituting the cultural landscape of the study site can play a major role in providing visitors with a sense of relaxation. The perception of a resting place over time may form a place attachment and identity of a specific area (Korani and Sam, 2022; Lee and Jeong, 2021). Like previous studies (Hung and Chang, 2021; Kim and Miller, 2019; White et al., 2010), this study may indicate that the feeling connected to the cultural landscape, as opposed to an urban environment, improves psychological health, encourages a high level of well-being, and reduces stress and anxiety.

Conclusion

This study builds on previous environmental psychology and heritage studies (Alcindor et al., 2021; Lowenthal, 2015; Sung and Brooks, 2022) that show that natural outdoor environments and cultural heritage can positively affect visitors’ mental health, well-being, and appreciation of a site, ultimately influencing their visiting patterns and sense of place attachment (Sung and Brooks, 2022). Understanding public appreciation as the core element of heritage management is significant because it profoundly affects visitors’ experiences of a site (Ababneh, 2021; McIntosh, 1999; Stegmeijer et al., 2021). Moreover, many countries are increasingly considering cultural landscapes as important cultural assets and the conservation thereof is necessary for forming the identity and attractiveness of an area, taking advantage of the power of nature and heritage for present-day needs and wants of visitors, and explicitly including this in spatial planning (Meskell, 2015; Stegmeijer et al., 2021).

However, empirical studies that consider the impact of natural outdoor environments and cultural heritage sites together are lacking, especially in considering visitors’ demographic traits, time of the day, season, and life stages with a focus on small-scale environments (Alcindor et al., 2021; Ababneh, 2021; Kjellgren and Buhrkall, 2020). Therefore, this study investigated how cultural landscape—a concept that comprises natural and cultural heritage—plays a role in visitor behavior patterns, considering gender, time of the day, season, and age groups using the open spaces of Gyeongbok Palace to bridge the gap between previous studies.

The major findings and implications of this study can be encapsulated as follows: First, the findings demonstrate that the cultural landscape plays a role in shaping visitors’ behavior. Additionally, there are significant variations in visitation patterns based on age groups and the days of the week. Notably, teenagers showed a strong positive correlation with weekday visits, especially during periods in 2020 when COVID-19 restrictions were in place and students attended online content-based classes (Kwon, 2021; Lee et al., 2020). Second, as recent news highlighting the importance of heritage and the growing demand for green spaces emphasizes the positive impact of cultural landscapes as relaxing, healing, and peaceful spaces away from frenetic work life (Ban, 2021; Choi, 2021), the data indicate a noticeable increase in correlation scores in 2021 compared to those in 2019, supporting the notion that heritage sites serve as healing and relaxing places for people to enjoy as they age. Finally, the findings also show that this cultural landscape can enhance visitor satisfaction and increase a region’s attractiveness by linking cultural heritage assets and other natural outdoor environments with positive benefits to its visitors. Taken together, the present findings support the importance of preserving and promoting cultural landscapes as integrated systems of natural and cultural resources, which has important implications for heritage policies and management strategies.

Internationally, the findings could be linked to Goal 3 under the Sustainable Development Goals, “ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being” and Goal 11, “making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.” In other words, these findings can provide related policies with insights to link cultural landscape design as an approach to ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being (United Nations, 2020). Nationally, these findings can be connected to the South Korean government’s primary goals for balanced national development (South Korean Presidential Committee for Balanced National Development, 2022) because the impact of the cultural landscape comprising nature and cultural elements can be more influential in shaping the attractiveness of an area because of the declining populations in small towns or rural areas (Alcindor et al., 2021; Stegmeijer et al., 2021).

The findings of this study also offer a theoretical framework for effectively harnessing the potential of cultural landscape elements. To illustrate, the South Korean government implemented the concept of Social Overhead Capital (SOC) between 2018 and 2022, wherein it actively promoted social and cultural service facilities such as gardens, community parks, and social welfare establishments within residents’ immediate neighborhoods (Sung and Ki, 2021b). The Office for Government Policy Coordination of South Korea defined community SOC as crucial public facilities designed to enhance people’s lives by providing fundamental amenities for daily existence, encompassing education, culture, and welfare (Government of the Republic of Korea, 2019). Nevertheless, this policy initiative faced criticism due to concerns over inadequate financial sustainability and insufficient private investment (Kim et al., 2021). Conversely, cultural landscapes as social and cultural public resources present a more viable option for achieving financial stability and effective management compared to other social and cultural public facilities, as they do not necessitate initial installation.

The UK government has implemented a policy that encourages residents to actively choose their favorite historical buildings to be included in their local authority’s list, highlighting the importance of considering residents’ preferences and needs in recent heritage policies regarding local cultural heritage sites (Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, 2021). This recognition underscores the significance of preserving cultural landscape elements and maximizing their potential for the benefit of residents, who can be the main group of visitors. By adopting targeted policy measures specifically tailored to accommodate the diverse needs and preferences of visitors at various stages of life, there exists an opportunity for the enhanced development of heritage management and policies (Sung and Ki, 2021a). This approach aims to create a more fulfilling cultural landscape experience by adequately addressing the distinct requirements of different visitors. Through the implementation of such policy measures and spatial planning strategies, cultural landscapes can be optimized to offer positive benefits to visitors, particularly those who need to escape from the stressful demands of modern life.

Despite this potential contribution to academic debates and heritage or landscape policies, the limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, this study did not consider visitors’ ethnographic and demographic dimensions, such as the differences between migrant groups and existing residents, different nationalities, and income levels, which could be important factors influencing visitors’ behavior patterns (Ababneh, 2021; Sung, 2022). Future follow-up studies could consider additional contextual elements, such as the aforementioned visitors’ ethnographic and demographic characteristics when analyzing the impact of cultural landscapes on visiting patterns. Second, other geographical studies with natural outdoor environments and cultural heritage could be investigated to gain a deeper understanding of the various impacts of cultural landscapes. Finally, considering that the aging population is rapidly increasing (BBC News, 2022) and the birth rate has been dropping sharply (Lim, 2023) in South Korea, qualitative follow-up studies may be necessary to investigate how those in their 60s and 70s or those who have younger children could improve their quality of life using the potential of cultural landscape.