An Analysis of Empowerment Perception and Needs According to Individual Characteristics of Forest Interpreters

Article information

Abstract

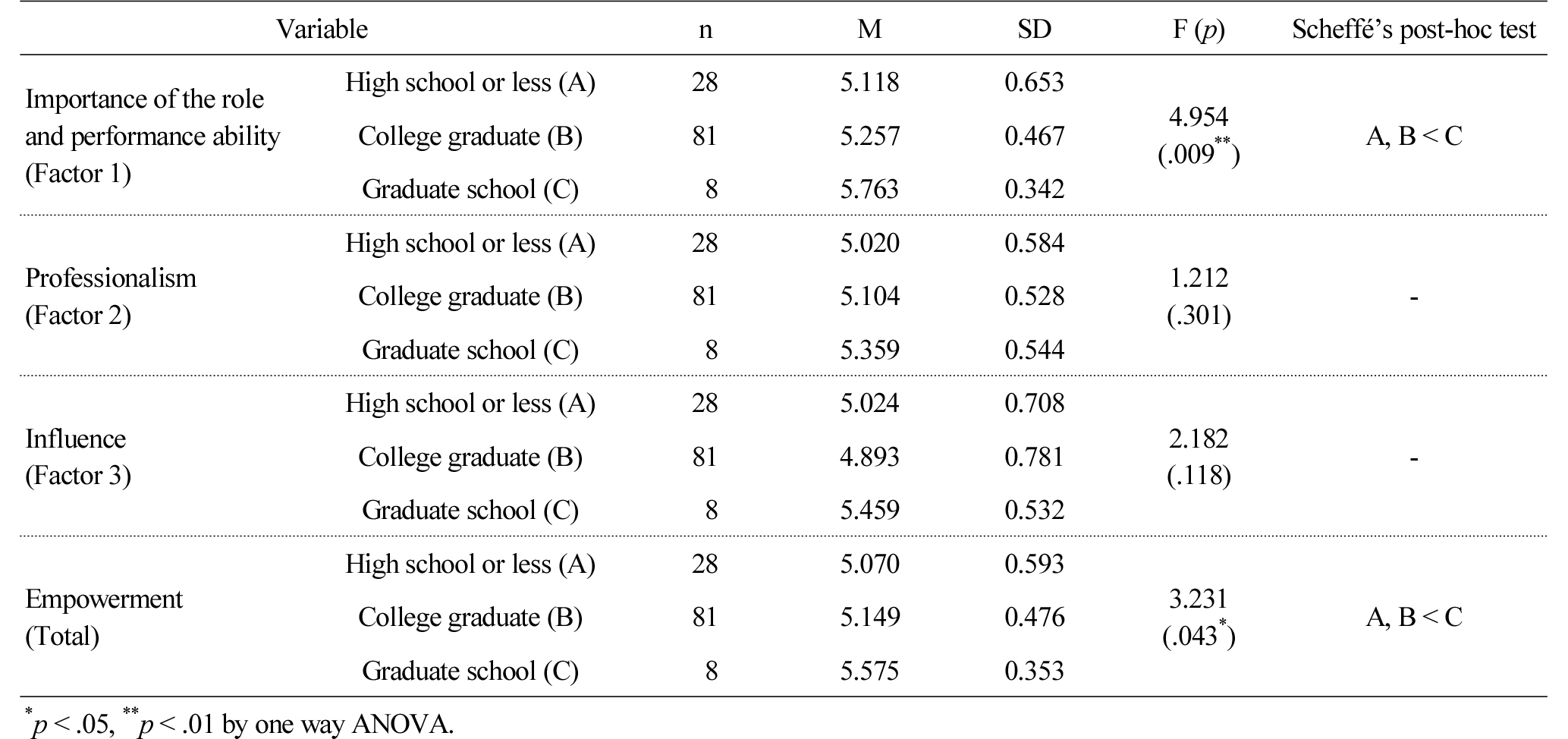

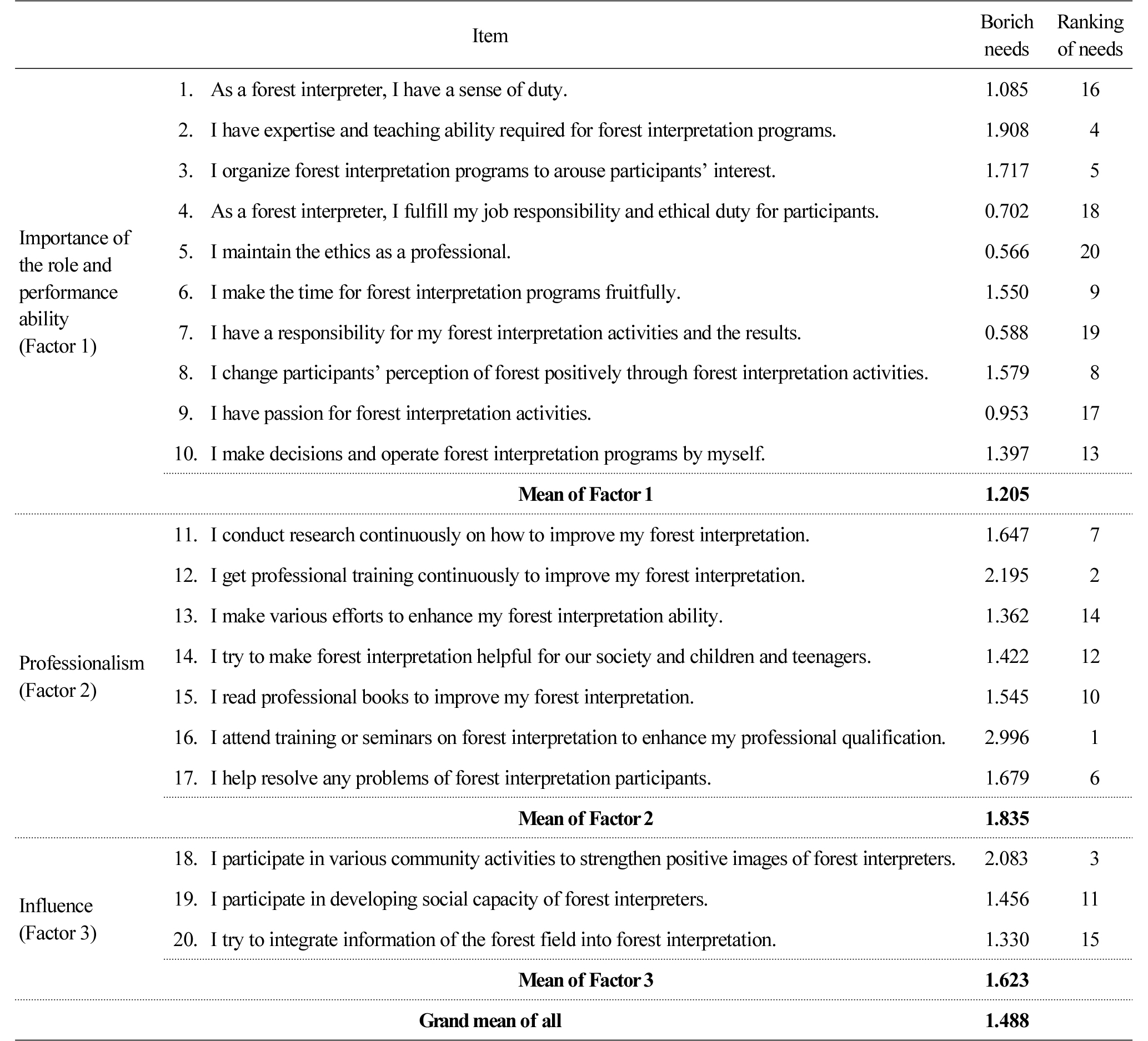

This research aimed to investigate the differences in empowerment perception and empowerment needs according to individual characteristics of forest interpreters. A survey was conducted with 117 incumbent forest interpreters who have been in the forest interpretation business consigned by the Korea Forest Service in 2017. The research results are as follows: First, the subjects prioritized ‘importance of the role and performance ability’ among the sub-factors of empowerment at both present and required levels, while ‘influence’ was rated relatively low. Second, as a result of analyzing the difference of empowerment based on individual variables of forest interpreters such as gender and age group, the entire empowerment and the sub-factors of both gender and age showed no significant difference. But the analysis on the difference of empowerment according to academic background of the subjects revealed that the group with a ‘Master’s degree or higher’ showed statistically and significantly higher scores than ‘high school graduates’ and ‘college graduates’ when it comes to ‘the entire empowerment’ (F=3.231, p〈.05). According to one of the forest interpreters’ individual variables, career length, ‘those who have worked as a forest interpreter for 10 years or more’ had statistically and significantly higher scores in ‘professionalism’ than ‘those with 3 years or less of experience’. Third, the forest interpreters’ Borich needs for empowerment was highest in ‘professionalism’, followed by ‘influence’ and ‘importance of the role and performance ability’. The rank was analyzed in details, and ‘participation in training courses and seminars on forest interpretation to improve professional skills’ took the first place. As this item is in the LH quadrant (Quadrant 4) with high needs and low present level in the IPA (Important Performance Analysis) matrix analysis, it is considered to be prioritized for the education of forest interpreters to improve empowerment.

Introduction

Research background and objective

Theoretical review

Research Method

Subjects

Empowerment measurement tools

Analysis method

Results and Discussions

Individual characteristics of respondents

Empowerment perception and needs of forest interpreters

Conclusion

Introduction

Research background and objective

The recent increase in national income and leisure time led to more and more visitors to forests, and the demand for new forms of forest welfare services is increasing as well such as forest education, forest healing and forest leisure and sports in addition to mountain climbing and visiting recreational forests (Korea Forest Service, 2013). The Korea Forest Service has also established a forest welfare master plan (2013-2017) to meet the diverse needs for forest welfare and is actively implementing related policies to contribute to the improvement of national health and quality of life.

Meanwhile, welfare mix that emphasizes the role sharing with the private sector in welfare is expanding worldwide. Welfare mix refers to various supplies performing the role of welfare such as resources and informal sector aside from the national welfare market, and in the field of forest welfare, this is expanding to the private sector from the government leading with the enactment of the Forest Welfare Promotion Act (2016). Accordingly, Korea Forest Welfare Institute was established in April 2016, which is a public institution in charge of actual affairs related to forest welfare services. Specialized forest welfare business is also established in order to invite participation of the private sector and build a new forest welfare economic system, establishing legal and systematic frameworks for industrialization of the private sector (Korea Forest Service, 2016).

Specialized forest welfare business increased by about 2.8 times from 104 in 2016 to 286 today, and the ratio of forest interpreters was highest at 74.1% among specialists that belong to this business (Korea Forest Welfare Institute, 2018). As such, it became possible to create a new market with new organizations like specialized forest welfare business, which made it important for members to have potential and flexible ability to respond in order to deal with environmental changes such as the administration system. In particular, in the field of forest education, environmental factors such as facilities are important for qualitative improvement of education, but human resources to deliver the forest education services are more important than anything.

Forest interpreters are experts conveying the value of forests and specialized knowledge to visitors of the forests (Ha and Kim, 2006), and quality of human service is an important competitiveness factor for their interpretation service (Choi et al., 2014). Recently, empowerment is emerging as a new perspective and variable to provide qualitatively excellent education (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990).

Many studies in the past have verified correlation between job-related variables and individual characteristics such as job training, job competency, job motivation and job satisfaction among interpreters providing forest or nature interpretation in national parks or forests like recreational forests. However, there is no research that evaluates the empowerment perception and needs of forest interpreters as a means to bring developmental changes to the organization and enhance work efficiency and role performance ability of forest interpreters.

Therefore, this study examines the differences in empowerment perception according to individual characteristics of forest interpreters and analyzes their empowerment needs, thereby seeking ways to improve the empowerment of forest interpreters.

Theoretical review

Empowerment

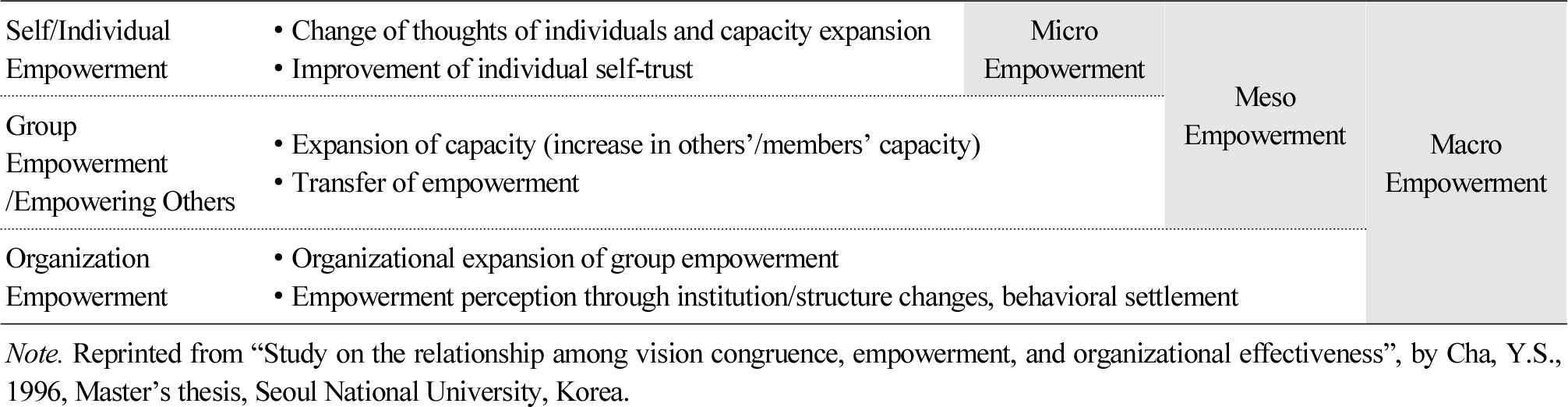

Empowerment literally means to give power. Here, power is a relational concept of how much control an individual or an organization has over another person or organization. Moreover, power for individuals indicates energy (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). In other words, empowerment means to energize (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). In this aspect, empowerment is basically motivation, especially internal motivation that gives meaning to task performance itself and leads to internal devotion instead of making one to perform a task by an external and instrumental motive (Jung and Park, 2005). Empowerment originates from the concept of motivation in behavioral science in the 1960s, and indicates the action or process in which voluntary behaviors of members are triggered as the leader gives them the right participate in decision making or motivate them, and claims that individual potential and growth serve as important foundations for organizational change (Jung and Park, 2005).

Empowerment has recently developed into a concept that changes an organization as well as relationships, as it enables members of the organization to find the best decision making methods in a rapidly changing environment like the modern society, and solve problems through synergistic interaction among members, thereby aiming at improving the ability to create new ideas (Kinlaw, 1995). Empowerment is a concept that leads from individual level (Micro) through the group level (Meso) to the organizational level (Macro), and is more mutually developmental than mutually independent (Cha, 1996). Capacity is improved based on these various levels, which creates a synergy effect of power and the influence is exerted among individuals, groups and organizations, thereby serving as a driving force of change.

In this aspect, empowerment must be understood not just as a management method or a fixed mental state of an individual, but as a process that expands an individual’s power (Conger and Kanungo, 1988; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). Various levels of empowerment may exist within one organization, and individuals can experience different levels of empowerment as time passes. Moreover, an organization’s characteristics and management methods or individual characteristics have a crucial effect on the process of expanding an individual’s power (Youn, 2001).

Previous studies in Korea about empowerment have been mostly on business administration and social welfare, but recently there are more and more studies in pedagogy, psychology, public health and physical education. These studies mostly analyze empowerment of members of an organization at the organizational level and its correlation with job satisfaction, organizational performance, organizational commitment, and self-efficacy (Kim, 2000; Kim, 2002; Lee and Lim, 2001; Lee, 2004). Recently, studies on empowerment of social workers are also increasing in order to improve the quality of social welfare services (Kang and Yun, 2000; Choi, 2002).

Forest interpreters

The forest interpreter training program was established according to the Forestry Culture and Recreation Act in 2006, and the forest education specialist qualification system was implemented based on the Forest Education Promotion Act in 2011. Accordingly, forest interpreters belonged to certain agencies of national forests such as recreational forests, arboretums and urban forests to provide forest education services for the public.

In 2017, the system was changed from the way the Korea Forest Service directly employed forest interpreters by policy and assigned them to different sites to the form in which the whole process is consigned to private specialized forest welfare businesses to provide forest education services, which was a turning point in terms of operation of the private forest educational institutions and groups. In other words, institutions and groups that include members with qualifications for a forest education specialist are registered on the Korea Forest Service as specialized forest welfare businesses, and can be put in charge of business by consignment of a forest education institution, thereby participating in the business independently (Korea Forest Welfare Institute, 2018).

Meanwhile, the philosophy pursued by interpretation, organization and skills of interpreters change as time passes, which also changes the role of interpreters as well as their capacities (Mullins, 1984).

Previous studies on forest interpreters analyze the job as a forest interpreter, develop a curriculum to cultivate the right capacity, or compare the differences in demand, importance and achievement related to job training programs, thereby proposing a suitable education method (Ha and Kim, 2006; Ha, 2006; Ko and Shin, 2011; Choi et al., 2014). Moreover, they analyze the correlation among factors that affect the job motivation and satisfaction of forest interpreters, or analyze the correlation among their level of expertise, individual characteristics and social environment, emphasizing that career, self-efficacy, social expectation and support infrastructure of forest interpreters are important elements that affect their expertise (Jo, 2009; Ko, 2012; Park and Jang, 2016).

Similar studies related to nature interpretation include the perception of national park staff about natural environment interpretation (Kim et al., 2005), perception of visitors about various environment interpretation media (Cho and Sung, 2014), and development and operation of an environmental education program in a natural recreational forest (Lee et al., 2001).

As such, the studies were mostly on individual characteristics and variables of forest interpreters such as job training, skills, motivation and satisfaction, as well as on operation and management of natural environment interpretation programs and perception on the use of interpretation media.

Research Method

Subjects

This study targeted forest interpreters currently in post that belong to arboretums, natural recreational forests, regional offices of the Korea Forest Service, and local governments participating in the forest interpretation consignment operating project of the Korea Forest Service in May 2017. The survey was conducted on 224 forest interpreters that participated in the ‘forest interpreter job training’ carried out in three sessions from May 11 to 19 at Forest Vision Center in Seoul and the Daejeon office of National Forestry Cooperative Federation. Among the collected copies of the questionnaire, 107 copies that omitted even a single item and not answered faithfully regarding the need and current level of empowerment were excluded, and total 117 copies effective for analysis were used.

Empowerment measurement tools

For the empowerment test, this study modified and used the questionnaire developed and used by Park (2006) based on the constructs of Fox (2001), Thomas and Velthouse (1990) and Short and Rinehart (1992) to be more suitable for forest interpreters. The empowerment scale consists of items on empowerment such as role importance, role performance ability, expertise and influence, with total 20 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale from ‘Strongly disagree’ (1 point) to ‘Strongly agree’ (6 points) as used by Fox (2001) and Park (2006). Higher score in the scale indicates higher empowerment.

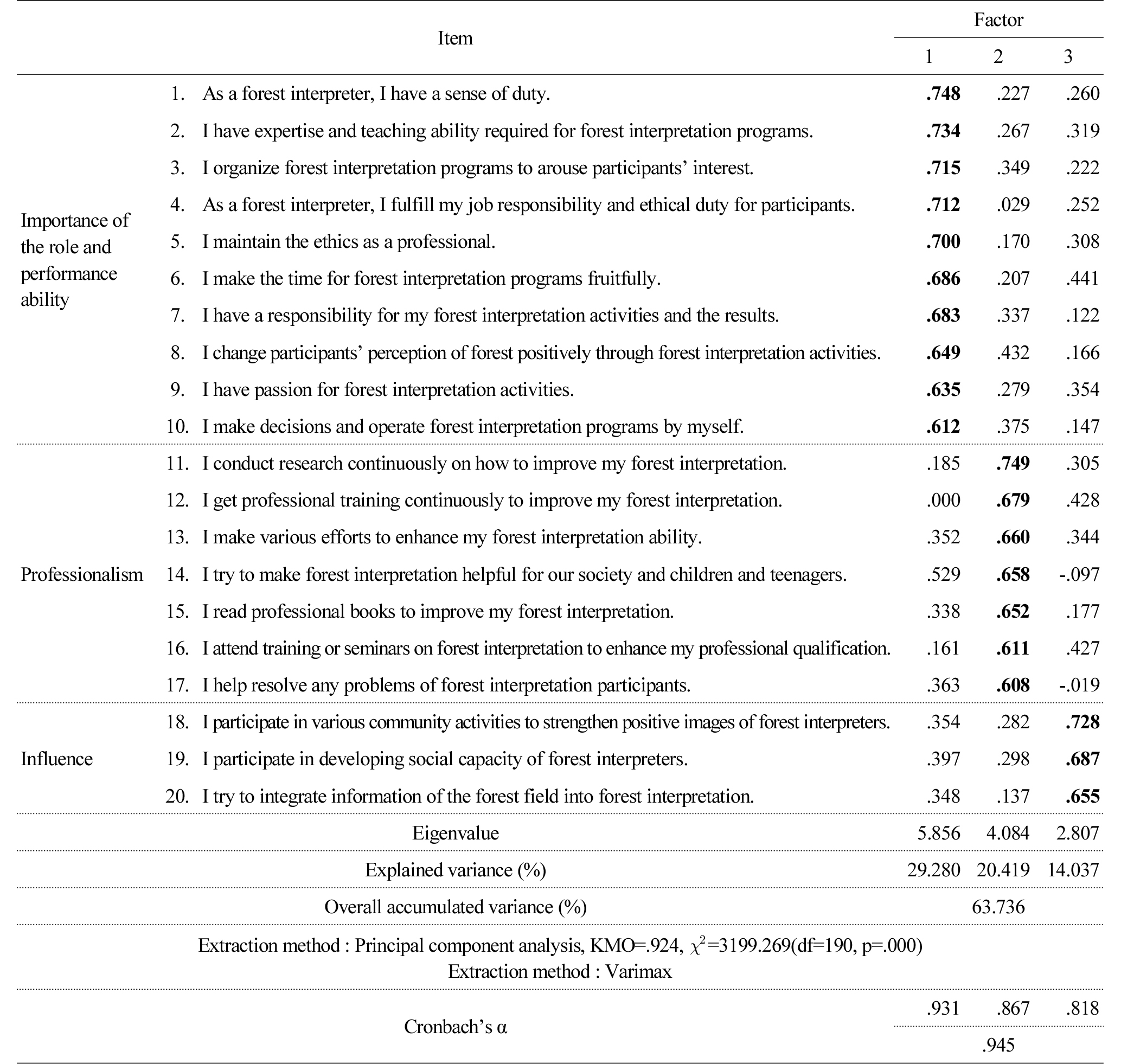

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to verify the validity of the items, and principal component analysis was used to extract the components of all measurement variables, and varimax rotation was adopted. Communality of items by the principal component analysis is the ratio explained by extracted factors. Thus, variables with low communality are excluded from the factor analysis, which are generally considered low if they are 0.4 or lower (Song, 2016). Based on the above, all 20 items were used without excluding any in the final analysis, as the communality all turned out to be 0.5 or higher. A reliability analysis was conducted to review the internal consistency of the empowerment test items.

Analysis method

The data collected in this study is analyzed using the SPSS 21.0 program, and descriptive statistical analysis, factor analysis, reliability analysis, independent samples t-test, ANOVA and Scheffé’s post-hoc test were conducted.

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to verify the validity of the items, and principal component analysis was used to extract factors about empowerment of forest interpreters, and varimax rotation was adopted. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used to verifiy that the chi-square (x2) is lower than the significance level of 0.05 or lower, and KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) was used to verify that the KMO is 0.5 or higher, after which a reliability analysis was conducted to verify the internal consistency of items (Hair et al., 1998).

The education needs of empowerment of forest interpreters applied the Borich formula generally used in needs analysis based on the research by Borich (1980) and Kim et al. (2001) (Equation 1). Needs analysis is a necessary procedure to help reform the education system for the education producers to meet the needs of education consumers (Baeg, 2003), and it is also important to prioritize the results of the analysis so that they can be actually used in decision making in the field (Kang, 2008). The Borich formula multiplies the sum of the difference of two levels in each case by the average of required competence level, and divides it by the total number of cases to obtain the needs. According to this formula, higher required competence level (RCL) and lower present competence level (PCL) indicate higher needs. This formula adds the difference of the two levels in each case, and thus the scope of the results is broader and it is easier to distinguish the items. This formula is one level upgraded compared to seeing the simple difference between ‘what should be’ and ‘what is’ as needs (Kim et al., 2001). The Borich needs analysis is used to assess the present performance level of competence in the relevant job and future needs among horticultural therapists, elementary school teachers and university professors (Kim, 2009; Kim, 2010). This formula is used in this study as it seems suitable to determine the present level and required level in assessing the empowerment competences of forest interpreters and prioritizing them.

Needs assessment formula: Needs = { ∑( RCLz - PCLy ) × mRCLx } / Nw (1)

where zRequired Competence Level

yPresent Competence Level

xMean of Required Competence Level

wTotal Number of Cases

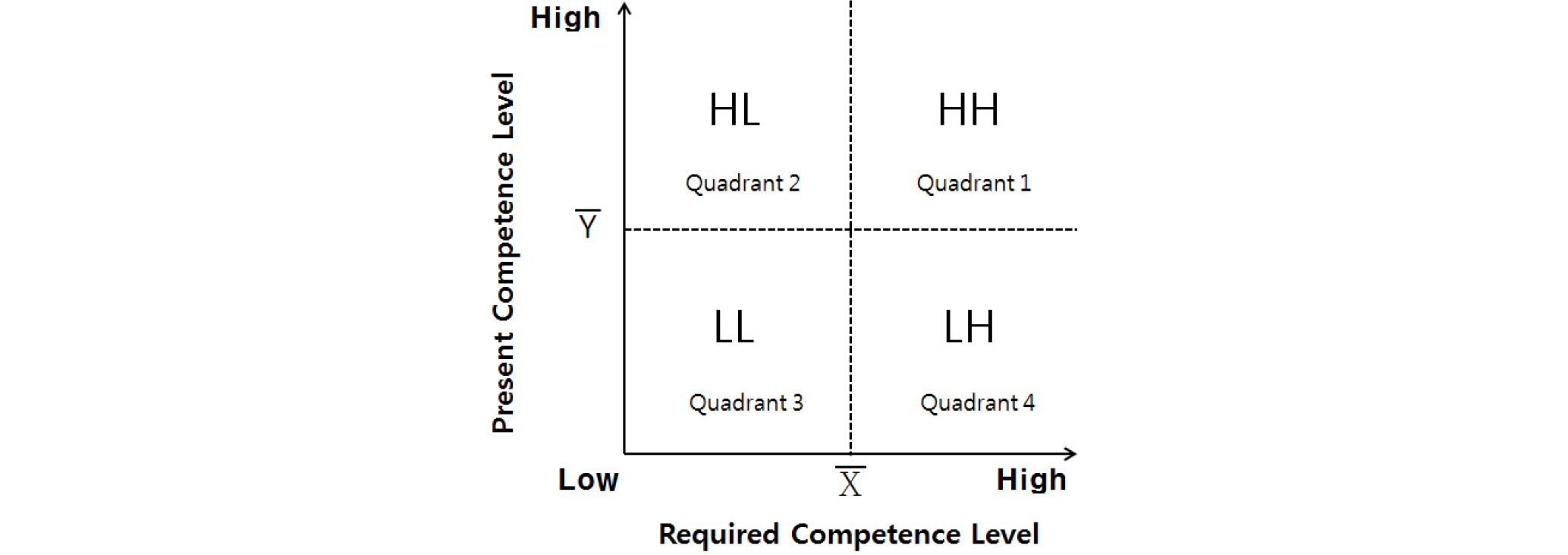

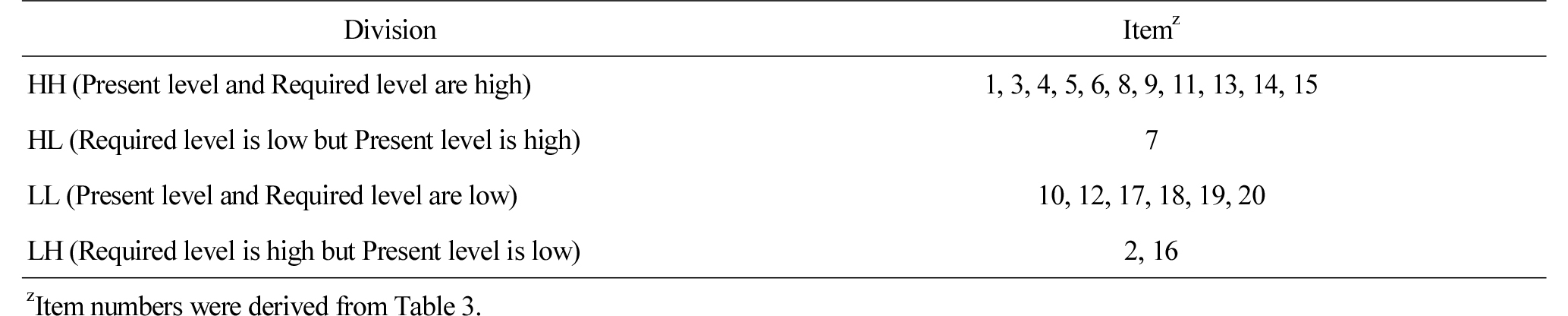

Moreover, the results of measuring the present level and required level of empowerment of forest interpreters were analyzed using the IPA (Important Performance Analysis) matrix presented by Martilla and James (1977). In other words, they are divided into four quadrants based on the average of the ‘required level’ of empowerment ( ) and the average of the ‘present level’ (

) and the average of the ‘present level’ ( ), and the numbers surveyed in each detailed element are placed as dots in the coordinates, dividing into ‘HH = quadrant with both high required level and present level’, ‘HL = quadrant with low required level but high present level’, ‘LL = quadrant with both low required level and present level’, and ‘LH = quadrant with high required level but low present level’. Through this, we intend to analyze the competences that most urgently need education to improve empowerment (Fig. 1).

), and the numbers surveyed in each detailed element are placed as dots in the coordinates, dividing into ‘HH = quadrant with both high required level and present level’, ‘HL = quadrant with low required level but high present level’, ‘LL = quadrant with both low required level and present level’, and ‘LH = quadrant with high required level but low present level’. Through this, we intend to analyze the competences that most urgently need education to improve empowerment (Fig. 1).

Results and Discussions

Individual characteristics of respondents

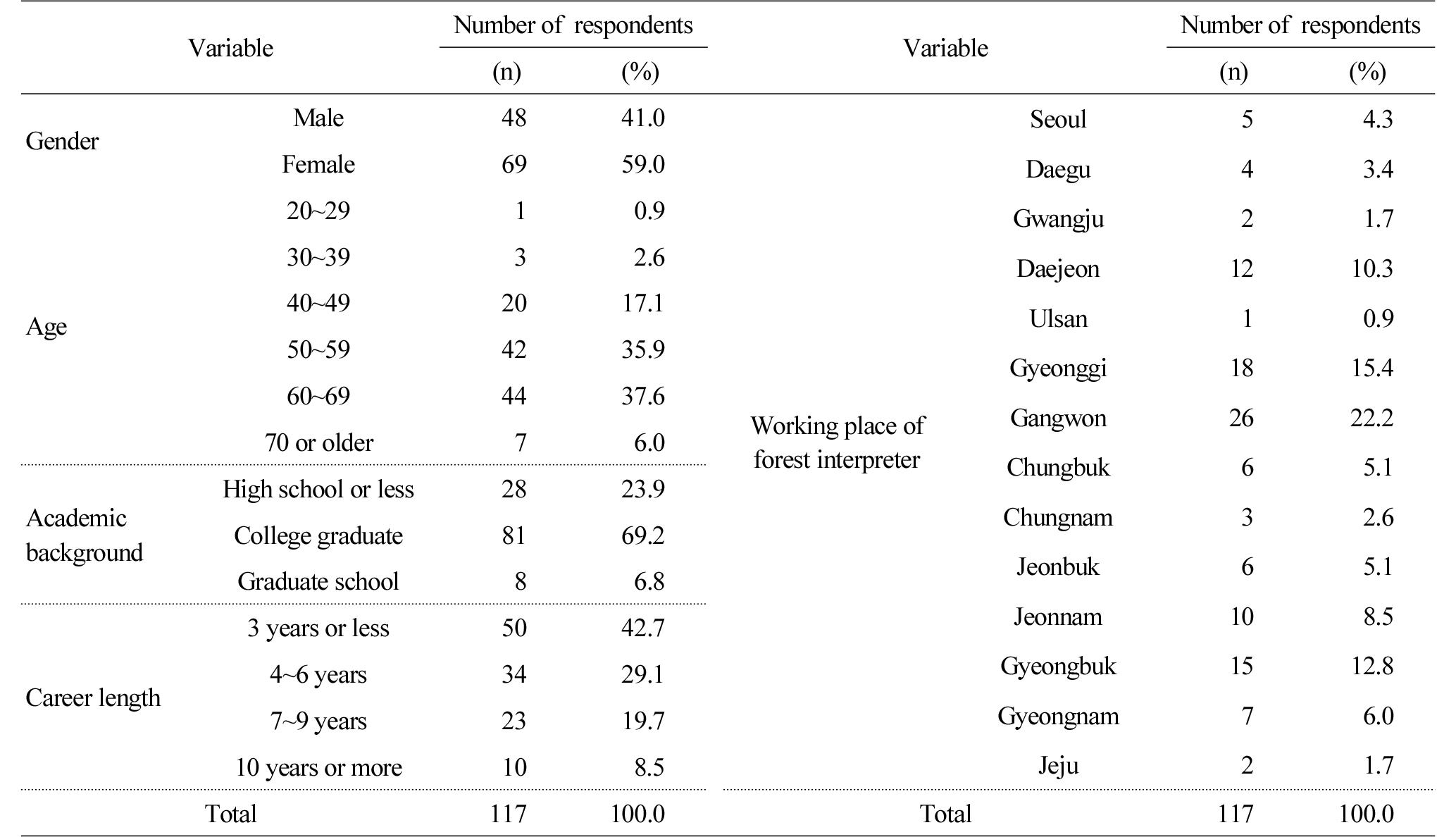

The individual characteristics of respondents are as follows (Table 2). There were 69 women (59.0%) and 48 men (41.0%), with 44 respondents in their 60s (37.6%), 42 in their 50s (35.9%), and 20 in their 40s (17.1%), indicating that middle age and elderly showed a high ratio. For education level, 89 respondents (76%) were college graduates or higher, showing a high ratio of high-level education. As for forest interpreter work experience, most of them had less than 3 years of experience (50 respondents, 42.7%), followed by 4-6 years (34, 29.1%), 7-9 (23, 19.7%), and 10 years or more (10, 8.5%). The respondents were working in 14 regions nationwide, such as 26 respondents in Gangwon-do (22.2%), 18 in Gyeonggi-do (15.4%), 15 in Gyeongsangbuk-do (12.8%).

Empowerment perception and needs of forest interpreters

Result of empowerment factor analysis

As a result of conducting the principal component analysis on the items of empowerment, they turned out to be suitable for factor analysis with x2=3199.269(df=190, p=.000), KMO=.924 (Table 3). There were total 3 sub-factors of empowerment. Factor 1 includes items related to the role importance and performance ability as a forest interpreter such as ‘As a forest interpreter, I have a sense of duty’, ‘As a forest interpreter, I fulfill my job responsibility and ethical duty for participants’, ‘I organize forest interpretation programs to arouse participants’ interest’, and ‘I make the time for forest interpretation substantial and fruitful’, and thus this factor is named ‘Role importance and performance ability’.

Factor 2 includes items related to reinforcing professionalism in forest interpretation such as ‘I conduct research continuously on how to improve my forest interpretation’, ‘I get professional training continuously to improve my forest interpretation’, and ‘I make various efforts to enhance my forest interpretation ability’, and thus this factor is named ‘Professionalism’. Factor 3 includes items related to the influence of forest interpreters such as ‘I participate in various community activities to strengthen positive images of forest interpreters’, ‘I participate in developing social capacity of forest interpreters’, and ‘I try to integrate information of the forest field into forest interpretation’, and thus this factor is named ‘influence’. As a result of Cronbach’s α analysis, ‘role importance and performance ability’ is .931, ‘professionalism’ is .867, ‘influence’ is .818, and ‘total empowerment’ is .945, showing internal consistency.

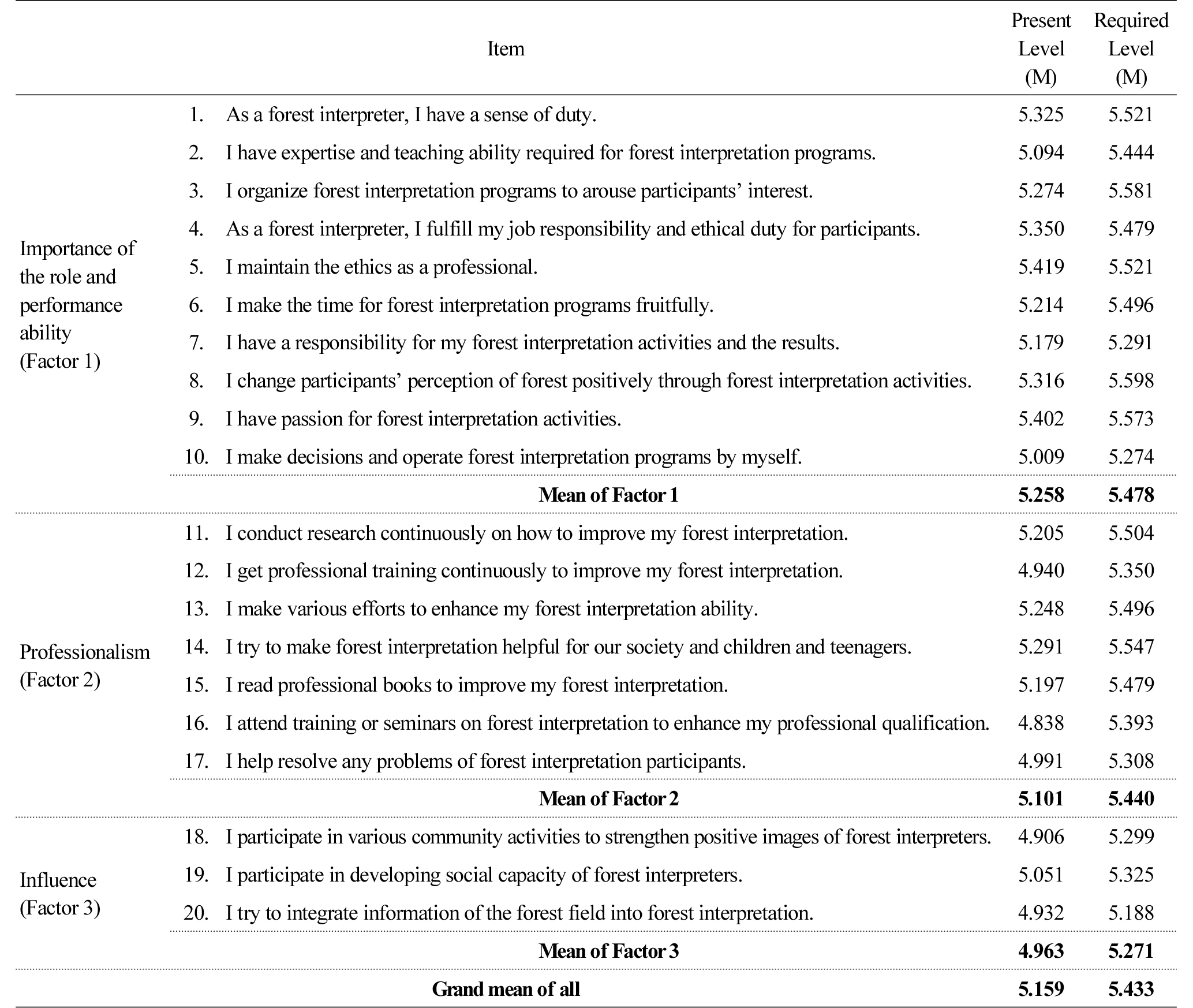

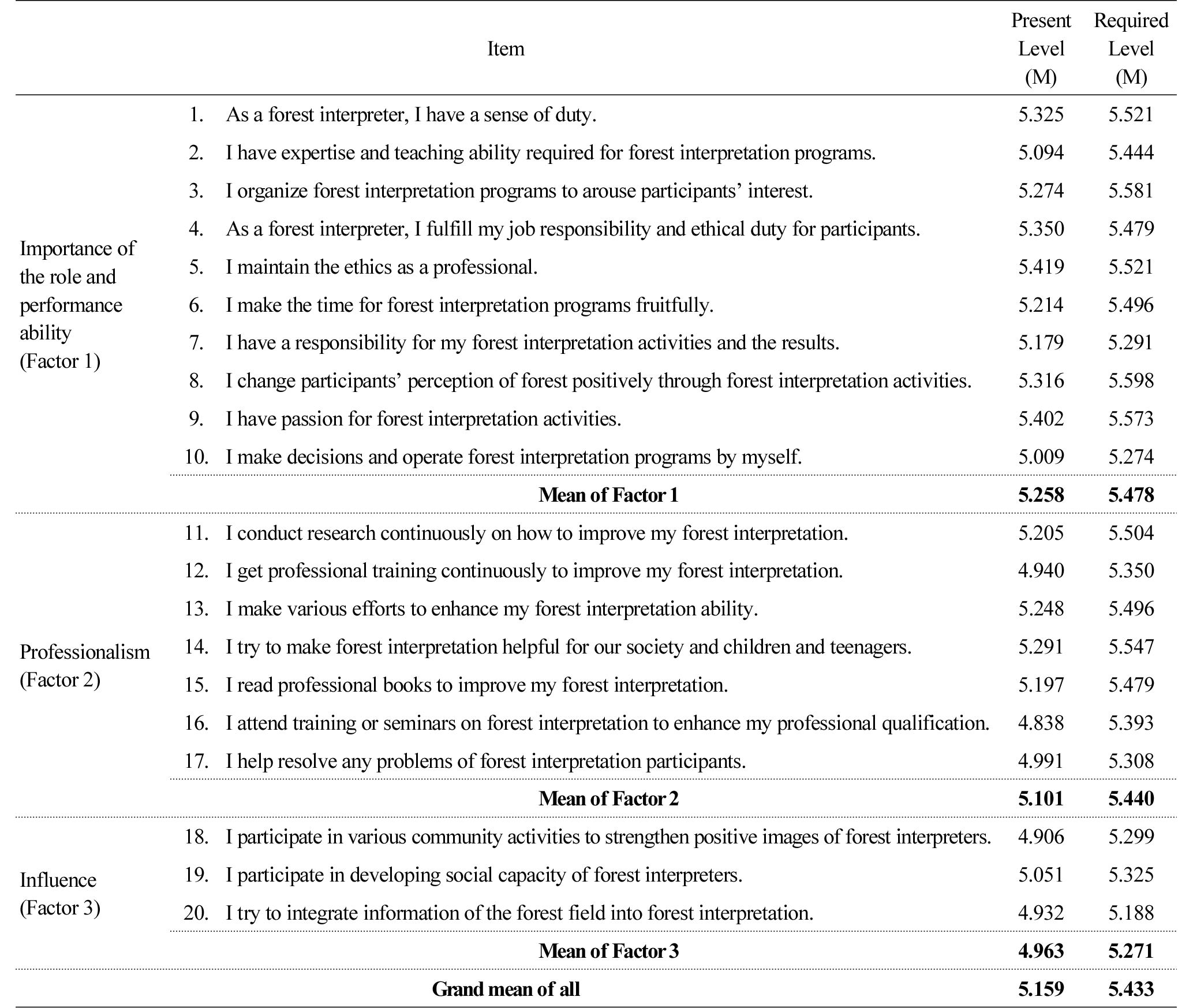

Empowerment perception of forest interpreters

Forest interpreters highly perceived the present level of empowerment in terms of maintaining ethics as a professional (M=5.419) and having passion for forest interpretation activities (M=5.402). Meanwhile, participating in education or seminars related to forest interpretation to improve expertise (M=4.838) was relatively low. Regarding empowerment of forest interpretations required in the future, they highly perceived the need for bringing positive change to the perception of participants about forests through forest interpretation activities (M=5.598), while they had relatively low perception on making efforts to integrate contents of the forest field into forest interpretation education (M=5.188). However, empowerment of forest interpreters required in the future showed the average of 5 points or higher in all items, showing that the required level of empowerment was highly perceived overall. By factor of empowerment, both the present level and required level considered ‘role importance and performance ability’ as most important, and the lowest factor at the present level was ‘influence (M=4.963)’, such as participating in community activities as a forest interpreter to strengthen positive images and develop social competency (Table 4). Therefore, to increase social influence of forest interpreters, it is necessary to enable them to exert autonomous discretionary power about their job through active communication among members of the organization. This will help forest interpreters to be engaged with their work more excitedly, and also increase social influence of forest interpreters through forest education in the long run.

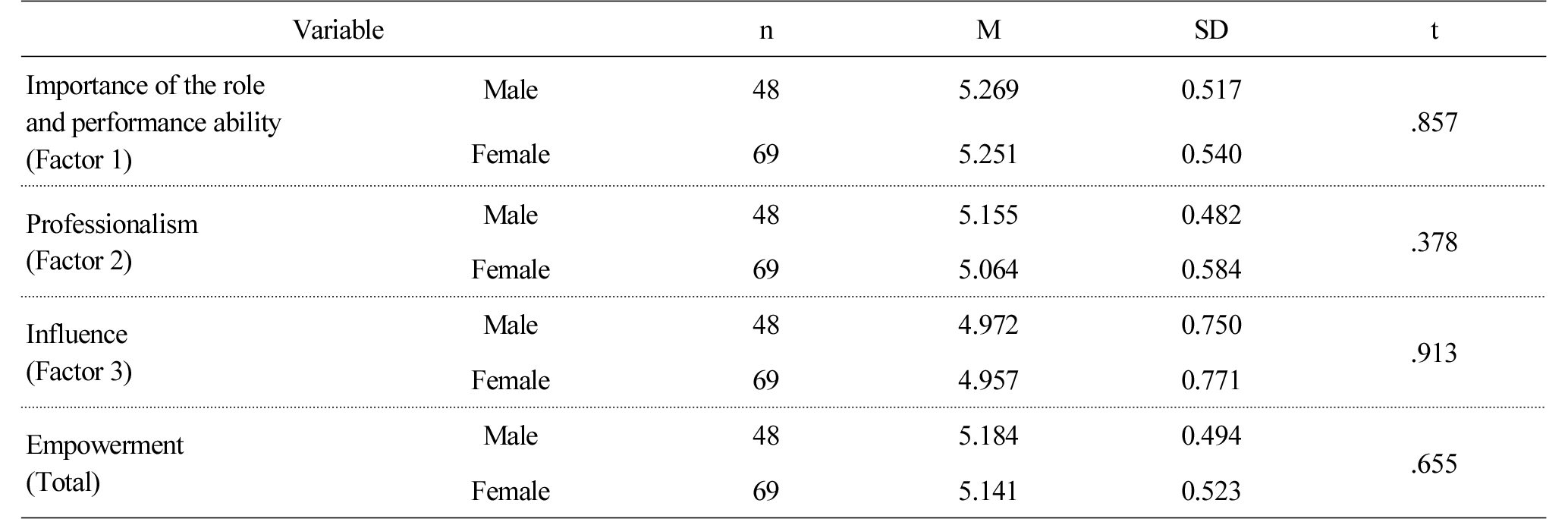

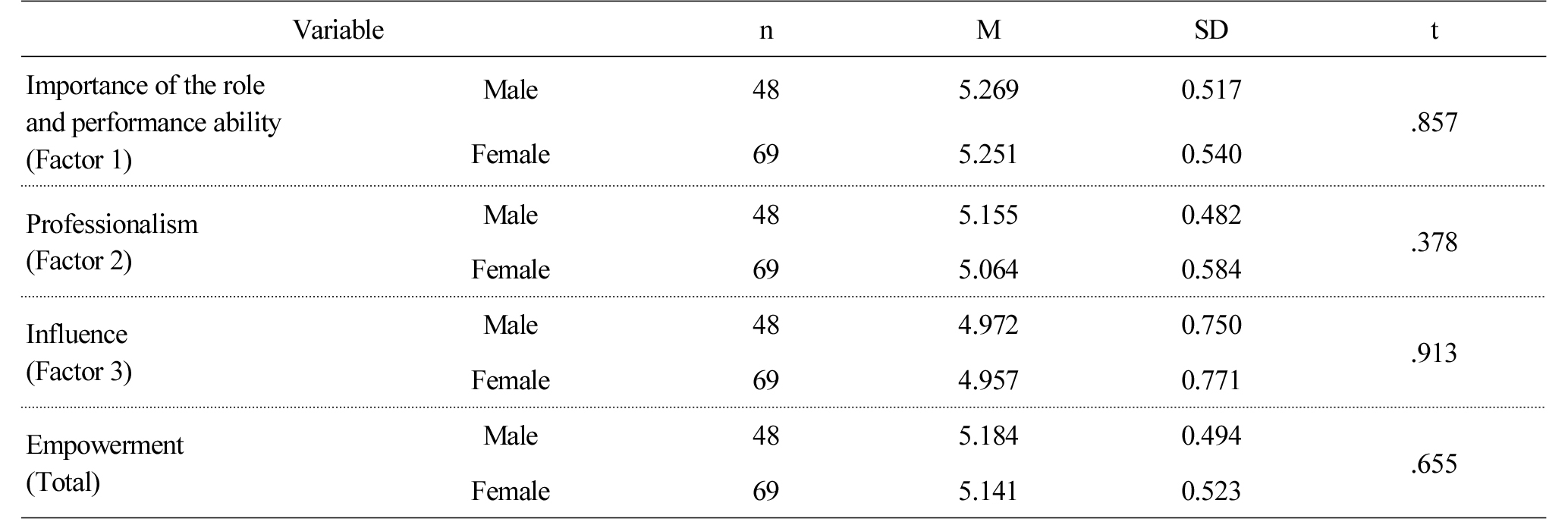

Empowerment perception according to individual characteristics of forest interpreters

As a result of analyzing the empowerment differences among groups according to gender as an individual variable of forest interpreters, men showed higher average than women in ‘total empowerment (M=5.184)’ and the sub-factors ‘role importance and performance ability (M=5.269)’, ‘professionalism (M=5.155)’ and ‘influence (M=4.972)’, but there was no statistically significant difference (Table 5). In other words, the sense of duty as a forest interpreter is an essential factor for them to effectively perform their tasks (Jo, 2009), and obtaining the ability to provide forest education as a forest education specialist, lead the public and having insight is related to the basic qualities and attitude of forest interpreters, and thus the empowerment perception of forest interpreters is unrelated to gender.

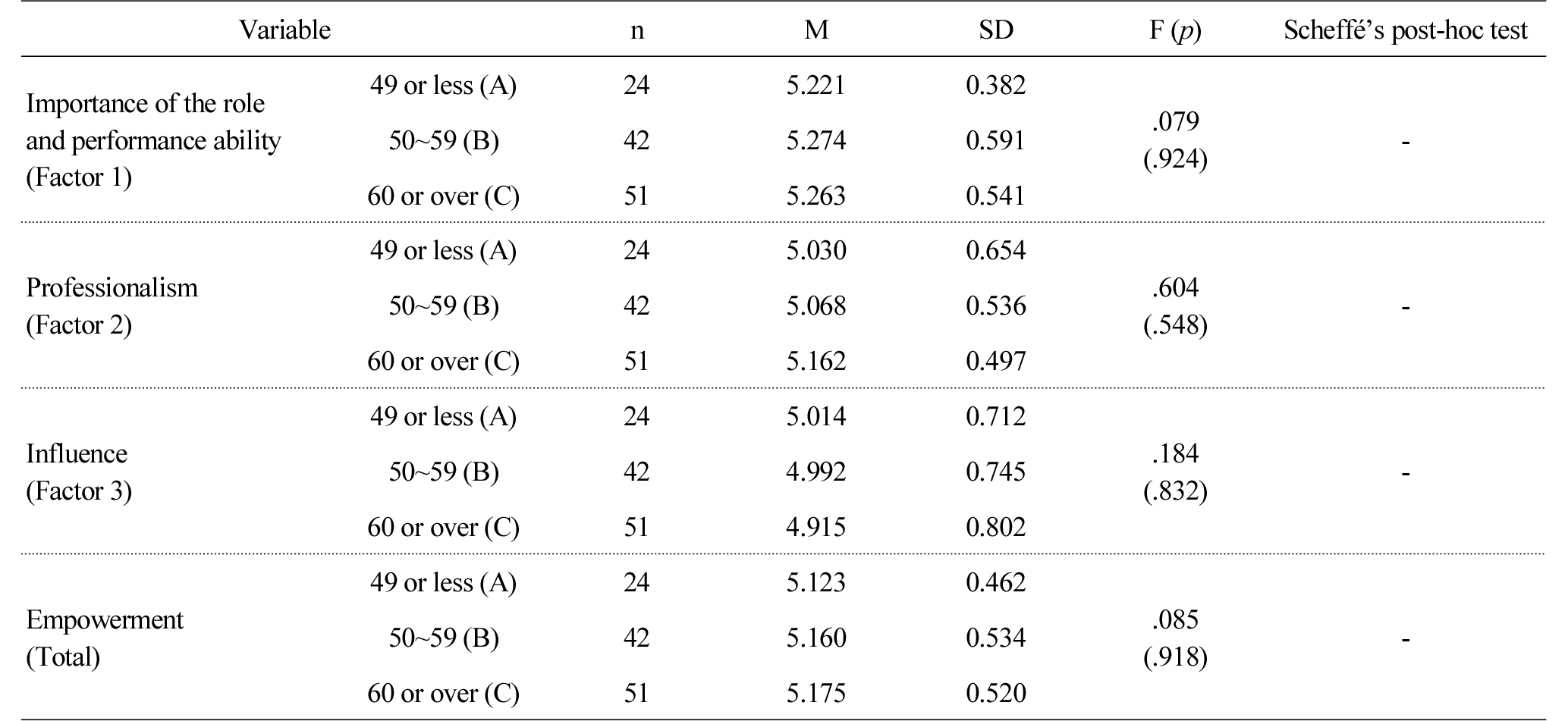

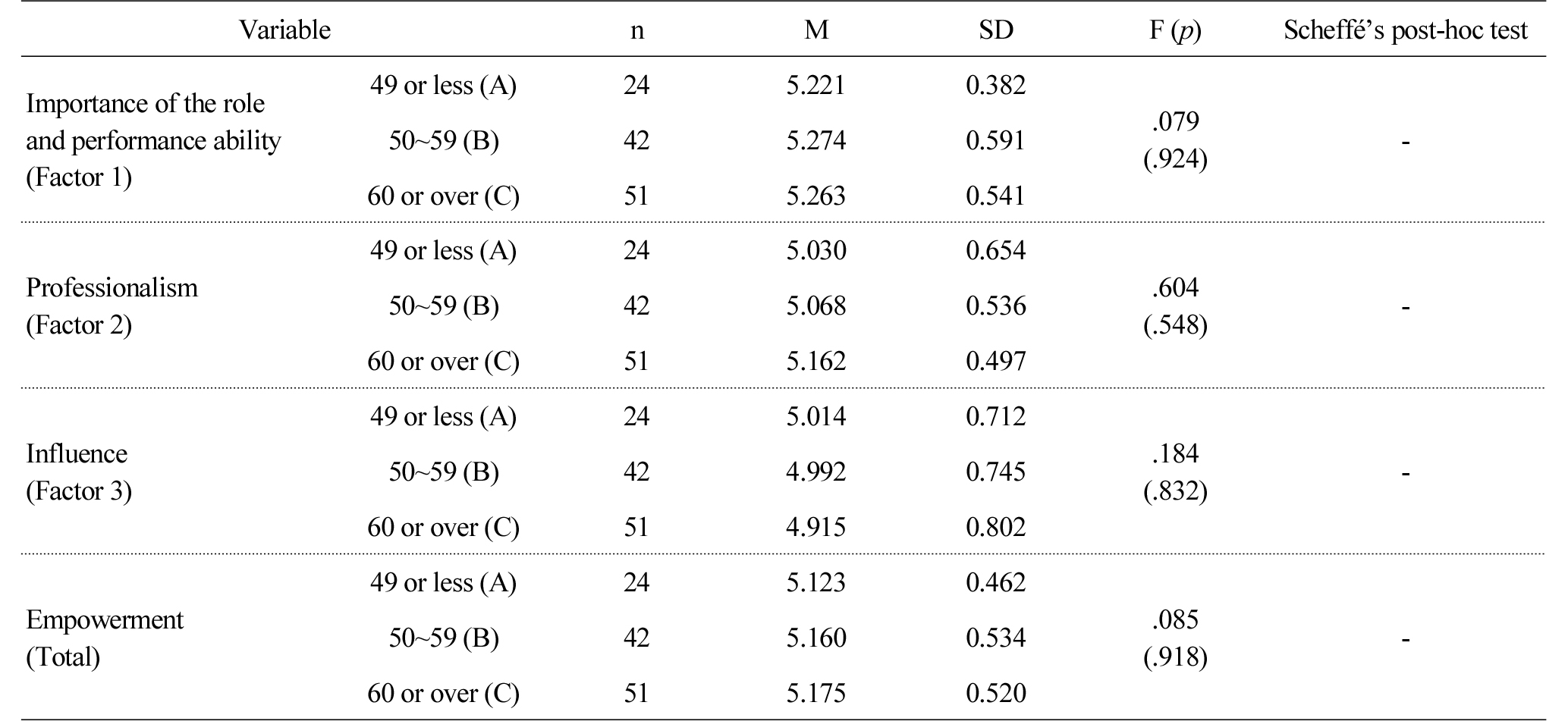

As a result of analyzing the empowerment differences among groups according to age as an individual variable of forest interpreters, the average was high among 60 or over (M=5.175) for ‘total empowerment’, while for sub-factors, the average was high among 50s (M=5.274) for ‘role importance and performance ability’, 60 or over (M=5.162) for ‘professionalism’, and 49 or less (M=5.014) for ‘influence’, but all of total empowerment and sub-factors did not show statistically significant differences according to age (Table 6). This indicates that empowerment perception of forest interpreters has no difference according to age, and this result is supported by previous studies verifying the relationship between age and professionalism and proving that age does not have a statistically significant relationship (Yoon, 1996; Kim, 2001; Hwangbo, 2003).

As a result of analyzing the empowerment differences according to academic background as an individual variable of forest interpreters, ‘total empowerment (F=3.231, p〈.05)’ and the sub-factor ‘role importance and performance ability (F=4.954, p〈.01)’ showed a statistically significant difference according to academic background. A Scheffé test was conducted to determine the differences among sub-groups of academic background, and as the result in ‘total empowerment’, ‘graduate school or higher (M=5.575, SD=0.353)’ showed higher score with statistical significance than ‘high school graduates or lower (M=5.070, SD=0.593)’ and ‘college graduates (M=5.149, SD=0.476)’ (F=3.231, p〈.05). As for sub-factors of empowerment, in both ‘role importance and performance ability’, ‘graduate school or higher (M=5.763, SD=0.342)’ showed higher score with statistical significance than ‘high school graduates or lower (M=5.118, SD=0.653)’ and ‘college graduates (M=5.257, SD=0.467)’ (F=4.954, p〈.01). This result is consistent with Lee (2005). In other words, higher education level helps forest interpreters to better understand their role’s importance and gives them more influence at work, which makes them to perceive that they can better perform their duty (Table 7).

As a result of analyzing the empowerment differences according to career as an individual variable of forest interpreters, ‘professionalism (F=3.016, p〈.05)’ among sub-variables of empowerment showed a statistically significant difference according to career. A Scheffé test was conducted to determine the differences among sub-groups by career length, and the result showed that ’10 years or more of experience (M=5.472, SD=0.380)’ showed higher score with statistical significance in ‘professionalism’ than ‘3 years or less of experience (M=4.975, SD=0.576)’ (F=3.016, p〈.05). Moreover, in ‘total empowerment’, 10 years or more of experience (M=5.425, SD=0.470) showed a higher average than 3 years or less of experience (M=5.094, SD=5.425) but did not show statistical significance. This result indicates that forest interpreters with at least 10 years of field experience obtain stability and confidence in job performance, thereby having power to control their education activities in case a problem occurs. As forest education specialists with field experience, they will be able to provide substantial advice and help related to running programs for forest interpreters that have relatively little experience. This result supports the study by Kim (2007). Therefore, as the career experience of forest interpreters increase, it will be helpful to provide all kinds of refresher training to develop their expertise and provide various education opportunities such as workshops in which forest interpreters with rich field experience can share their know-how and experience in order to increase empowerment of forest interpreters (Table 8).

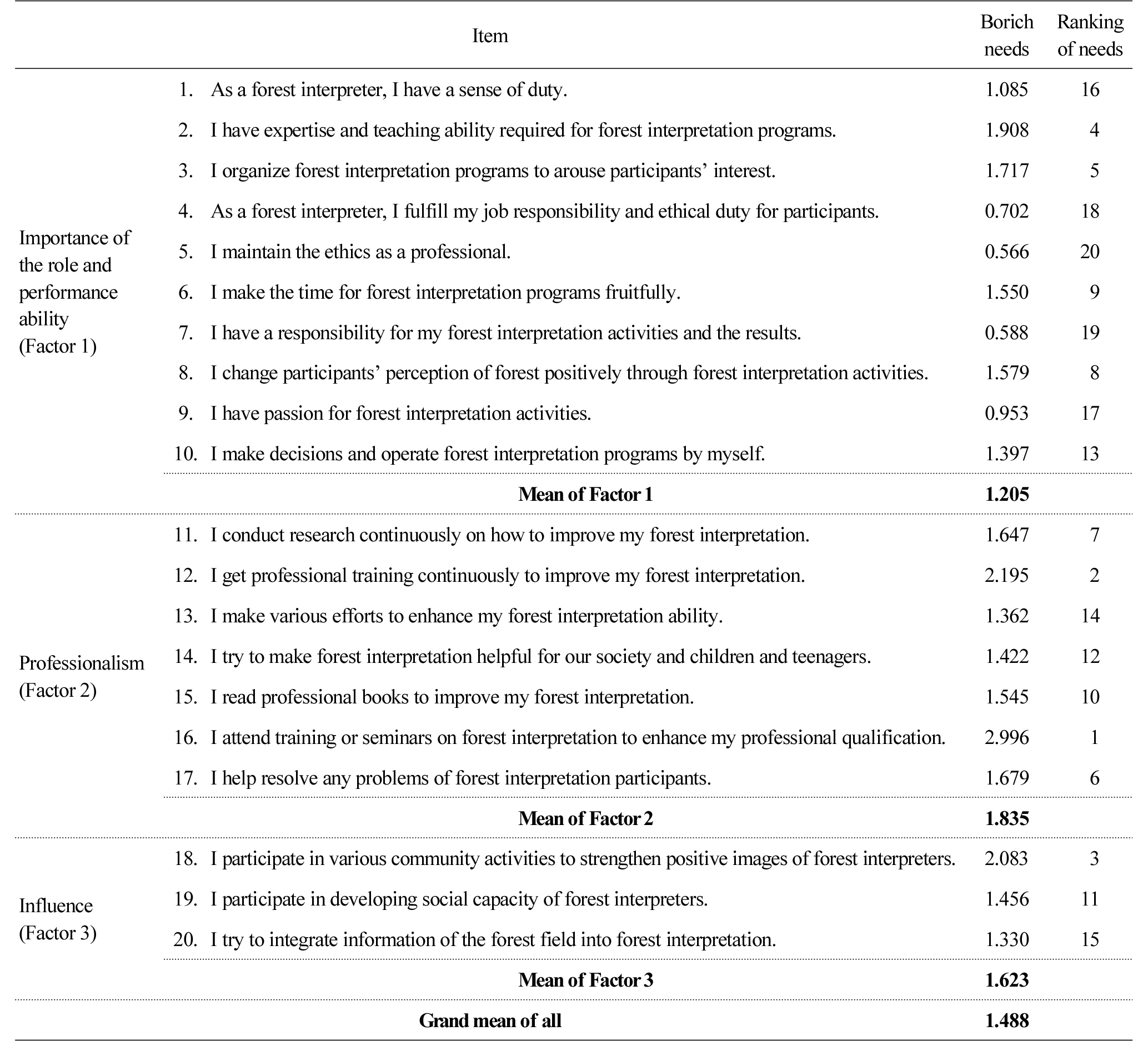

Empowerment needs of forest interpreters

As a result of Borich needs analysis on empowerment of forest interpreters (Table 9), the area with highest empowerment needs was ‘professionalism (M=1.835)’. In other words, to improve expertise, they shall participate in education or seminars related to forest interpretation (2.996), constantly receive specialized training to improve forest interpretation (2.195), operate forest interpretation programs to help solve the problems faced by participants (1.679), and conduct continuous research on how to improve forest interpretation (1.647). That is, the need for ‘professionalism’ was highest among sub-factors of empowerment because forest interpreters perceive that this area is currently weak, and they intend to strengthen their professionalism. This result is supported by Ko and Shin (2011) who emphasized the need for specialized training and constant reeducation of forest interpreters.

Following professionalism, the area with second-highest needs was ‘influence (M=1.623)’, such as promoting the positive image of forest interpreters by participating in various community activities (2.083), developing social competency (1.456), making efforts to integrate the content of the forest field in to forest interpretation programs (1.330) and thereby increasing social influence of forest interpreters. This result originates from how forest interpreters desire to regain pride by obtaining recognition for their social competency.

Finally, there was relatively low need for ‘role importance and performance ability (M=1.205)’. However, the present level has somewhat reached an ideal level with an average (M=5.258) higher than 5, which is supported by Son and Ha (2014) proving that forest interpreters consider their job as a professional career, feel rewarded by doing interpretation activities, and show high satisfaction with role importance and performance.

According to the empowerment IPA matrix analysis, 11 items appeared on the “HH” quadrant that highly perceives both required level and present level. For “HL” quadrant, ‘7. I have a responsibility for my forest interpretation activities and the results’ showed low required level but high present level. For “LL quadrant’, total 6 items showed low present and required level including 3 items related to ‘influence’ such as ’18. I participate in various community activities to strengthen positive images of forest interpreters, 19. I participate in developing social capacity of forest interpreters, and 20. I try to integrate information of the forest field into forest interpretation’, and these items can be gradually improved.

Finally, there were 2 items located in “LH” quadrant with high required level but low present level perceived by forest interpreters, such as ’16. I attend training or seminars on forest interpretation to enhance my professional qualification’ and ‘2. I have expertise and teaching ability required for forest interpretation programs’. These items shall be in top priority to improve empowerment of forest interpreters as items related to intensive education and professionalism of forest interpreters. The result about needs for intense education such as related training or seminar attendance is consistent with the result of top priority in the Borich needs analysis by item in Table 10 (Fig. 2, Table 10).

Conclusion

This study is conducted to determine the differences in empowerment perception according to individual characteristics of forest interpreters and present ways to improve their empowerment by determining the present and required levels in assessing empowerment and prioritizing them.

The results can be summarized as follows.

First, the empowerment factor analysis on forest interpreters showed that empowerment is classified into three factors such as ‘role importance and performance ability’, ‘professionalism’, and ‘influence’. Forest interpreters perceived ‘role importance and performance ability’ as the most important among sub-factors in both the present and required level, whereas ‘influence’ had relatively low perception. This result indicates that forest interpreters consider it more important to well determine their own roles and duties as forest education specialists and smoothly operate the programs than to increase their status and influence as forest interpreters in the community. Therefore, it will be possible to improve empowerment of forest interpreters by enabling them to exert autonomous discretionary power about their duties through active communication among members of the organization in order to increase their social influence.

Second, as a result of analyzing empowerment differences among groups according to gender and age as individual variables of forest interpreters, there was no significant difference in total empowerment and sub-factors by gender or age. However, as a result of analyzing empowerment differences according to academic background of forest interpreters, ‘graduate school or higher (M=5.575)’ showed higher scores with statistical significance in ‘total empowerment’ than ‘high school graduates or lower (M=5.070)’ and ‘college graduates (M=5.149)’ (F=3.231, p〈.05). Furthermore, the score was high with statistical significance in ‘professionalism’ among sub-factors of empowerment among ‘10 years or more of experience (M=5.472)’ than ‘3 years or less of experience (M=4.975)’ (F=3.016, p〈.05). This result shows that higher education level makes forest interpreters better understand the role’s importance and have greater performance ability, and forest interpreters with at least 10 years of field experience have greater expertise in knowledge and skills than forest interpreters with less than 3 years of experience.

Third, as a result of Borich needs analysis about empowerment of forest interpreters, the need was highest for ‘professionalism (M=1.835)’ followed by ‘influence (M=1.623)’ and ‘role importance and performance ability (M=1.205)’. By detailed item, the top priority item was ‘attending training or seminars related to forest interpretation to enhance professional qualification. Moreover, this item is also included in the LH quadrant (Quadrant 4) with high need but low present level in the IPA matrix analysis, which indicates that it must be given top priority in training for greater empowerment of forest interpreters.

The results above lead to following suggestions to enhance empowerment of forest interpreters. First, support must be provided for intensive learning such as education opportunities including various job training programs and seminars for forest interpreters to enhance their expertise as forest education specialists. Furthermore, as the content of education required may vary according to academic background or career of forest interpreters, it is necessary to develop step-by-step job training programs. In addition, providing various education opportunities through seminars where forest interpreters with rich field experience can share their know-how and experience will contribute to reinforcing empowerment of forest interpreters. Finally, it is necessary to focus on reinforcing individual and group empowerment so that forest interpreters can autonomously participate in decision making and motivate their roles and duties while coping with the changing environment.

The limitation of this study is that the study results cannot be generalized regarding the empowerment perception according to individual characteristics of forest interpreters, because there were a few samples of forest interpreters that participated in the study. Therefore, follow-up research must conduct a detailed analysis of related variables that can assess and reinforce the competencies and expertise of forest interpreters by collecting sufficient samples.